On June 1, 1453, the district of Galata surrendered to Sultan Mehmed II according to an ahdname (treaty); most of the population and buildings were taken over by the Ottomans. On the order of this ahdname and in accordance with Islamic law, the lives and properties of the local residents were put under eman, or the sworn assurance of the sultan. As foreigners from Europe and the Levant claimed in the nineteenth century, this ahdname did not have autonomy in regards to the internal administration of Galata. By appointing a subaşı (voivode) and a qadi immediately after the conquest, the sultan put Galata under the direct administration of the Ottoman government. During the Byzantine period, the Genoese had surrounded the city with fortified walls and transformed it into an autonomous Genoese colony. This situation was subsequently abolished under Ottoman administration. According to the 1455 Ottoman census, Galata’s non-Muslim population was divided into three categories: the Genoese and Venetian merchants who temporarily came to the city; the local Genoese who had become Ottoman subjects; and the Greeks, Jews, and Armenians who had settled down during the Genoese period. Genoese merchants were granted capitulations, while other Genoese became subjects of the Ottoman Empire, as accorded by the dhimmi (non-Muslim citizens) policy of the Ottoman Empire. Sultan Mehmed II paid due attention to ensuring that Galata, the center of trade with Europe, remained an active commercial district. To this end, he announced that those who had fled could reclaim their houses and property if they returned within three months. According to the 1455 census, some of those who had fled the city did in fact return. Most of those who had fled Galata were Genoese or Greek. According to the records, this group included only two Armenians but no Jews. It appears that the Jews, Armenians, and Greeks who had been against the Genoese control pressed for the surrender of the Galata castle to the Ottomans.

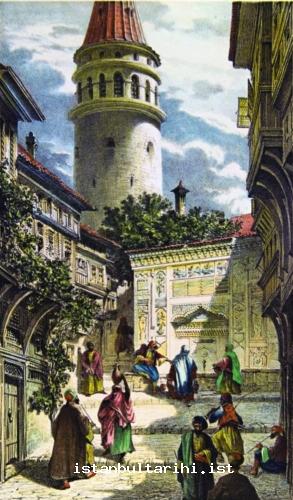

As new districts were established to accommodate the increasing population of Galata during the Genoese period, new walls were constructed to protect the enclave. Eventually, these new walls, together with preexisting inner walls, turned Galata into a five-section castle. After the Ottomans conquered the area, the sultan ordered the demolition of certain segments of the walls that had blocked entrance by road to the city, thus protecting it; however, the city maintained a similar structure to what had existed during the Genoese period. The first Genoese contrata—i.e., the region between Azerkapı and Karaköy—expanded towards the large tower and remained as the district’s liveliest region of commerce during the Ottoman period. Genoese guilds, both old and new, and some major Latin churches (St. Michele, St. Francesco, Santa Anna, Santa Maria, St. Domenico, and St. Zani) are located in this region. Jews generally lived in Karaköy and Yüksekkaldırım on the eastern side of the castle; Greeks lived between the Galata Tower and the first Genoese castle, and along the banks of Golden Horn from Karaköy to Tophane; Armenians tended to live on the slopes behind these areas. According to the 1455 census, the Greeks formed a demographic majority in Galata. The second largest group consisted of those of Latin origin (Genoese, Venetians, and the Catalan); the third largest group was those of Armenian origin; those of Jewish origin constituted the smallest group. It took the Turks half a century to establish a population in Galata; they were concentrated mostly in the isolated western part of the city. In the first five to ten years of the Ottoman period, marine azaps and kaptan (captains) were among the first Turkish settlers. Additionally, janissaries working at the Galata Tower came to settle in its immediate surroundings. Apart from the military classes, a wool merchant, fur merchant, bath attendant, blacksmith, and an embroiderer were among the first Turkish settlers. Galata was rapidly Turkified in the subsequent periods. According to a vakfiye (endowment deed) from 1481, the number of Turkish neighborhoods had come to reach twenty; at this time, there were thirteen Italian neighborhoods, eight Greek, and six Armenian neighborhoods. According to the results of the 1478 census, carried out by Qadi Muhyiddin, there were 592 Greek Orthodox households, 535 Muslim, 332 Latin (Efrenciyan or Catholic European), and 62 Armenian. Even in 1478, 49 percent of the population was Muslim. Christians were forbidden to settle in the Muslim districts, but merchants and tradesmen worked together in the market place and tradesmen guilds in spite of religious difference.

One of the most important effects of the Ottoman conquest was that Galata became more integrated with Istanbul in all aspects. Galata grew to represent Istanbul’s window to Europe, not only in respect to commerce, but also in terms of the social experiences of its residents. The chronicler of Mehmed II, Tursun Bey, said (around 1490), “if you would like to cross from Istanbul to Frengistan (i.e. Galata), it is enough for you to pay one akçe to the boat.” Under the Ottoman administration and from 1453 to 1490, the notary records of the Genoese in Galata reflect the continuation, from earlier periods, of their free lifestyle and commercial life. Ottomans afforded the Genoese community, which they referred to as the Magnifica Comunit di Pera, the right to regulate their internal affairs under the governance of a protegeros (kethüda or chamberlain). In the 1540s, Rüstem Pasha built a bedesten and an inn in the place of old St. Michele Church, therein creating a safe commercial center for merchants and their valuable imported goods. Galata was also the main storehouse for goods of Aegean origin, such as olive oil and wine. On the other hand, when the district of Kasımpaşa became the main shipyard and base for the Imperial navy in the sixteenth century, Galata naturally developed into an important site for sailors and marine activities. At the beginning of the seventeenth century, the entire Catholic European population of Galata was calculated to be 1,100 people. However, this figure should be amended with the addition of 500 emancipated slaves and 2,000 prisoners who had been held in naval dungeons at the time. In 1765, Galata’s European population was rather small, including only 17 Germans, 33 Frenchmen, and 13 Italians. We learn from the Galata court register that these foreign residents appealed to the district’s qadi in the event of personal grievances. Just as in the Genoese period, commercial life in the Ottoman period was concentrated around the Perşembe Pazarı Street, also known as Orta Hisar.

In this era, crossing from Istanbul to Galata was achieved by passing through the Perama / Fish Market gate. Later, the destination of this short journey came to be either the Yemiş or Balat ports. Engravings made at this time show ships docked en masse at these docks. According to the vakfiye of Hagia Sophia, two market places, one customs weighing office, one fruit weighing office, one tuzhane (salt factory), one candle factory, three paint factories, seven inns, and four hundred and twenty shops are mentioned as belonging to Galata. In the imperial market place in this region (Han-ı Sultani), there were three hundred and sixty-one shops; this was the main market place of the region. Many Jewish merchants also settled in this region of the city, which had previously been a place of settlement for the Venetian Bailo and merchants.

As for the establishment of Beyoğlu, at first there were vineyards, gardens, and cemeteries located beyond the upper walls of Galata, an area that was also referred to as “Pera Bağları.” After the construction of Galatasaray, which housed training facilities for the içoğlanları (young attendants at the palace), settlements grew up around it. During the reign of Selim II (1566–1574), European ambassadors started to build summer mansions in the region known as “Frenk Beyoğlu” or just “Beyoğlu,” an area which also housed the palace of the Venetian Aloisio Gritti, a man who was close to the sultan. Thus, the region of Beyoğlu beyond the walls of Galata began to develop. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries new ethnic elements began to gather in Galata. Because of Mehmed II’s support for the Florentines against the Venetians, Florentine houses of commerce were established in Galata between 1463 and 1520. The annual revenues of these houses could be as much as six hundred thousand gold pieces. But over time, these houses of commerce were replaced by similar ones of Venetian origin. As in the Venetian period, Galata functioned as a storehouse in which goods from the East and West were traded; of special importance was trade in thin woolen European fabrics and Persian silk. This trade constituted a major source of wealth for the republics of Genoa, Florence, and Venice. Among the other ethnic groups that settled in Galata were the Arabs. Since 1569, and especially in 1610, Andalusian migrant Arabs settled in Galata en masse. This explains in part the renaming of the St. Domenica Church as the Arab Mosque.

In the eighteenth century, there were generally few Europeans in Galata. Upon the development of strong commercial ties between the Ottomans and the Europeans, Europeans once more started to settle in Galata. According to the observations of Charles White in the 1840s,1 affluent Turks had started to shop in Beyoğlu instead of the Grand Bazaar. Pera’s famous high street, full of hotels, entertainment venues, and shops selling European goods, gave life to the already-cosmopolitan Beyoğlu district. During the Crimean War of 1853 to 1856, the cosmopolitan nature of the district grew even further. Europeans, and especially the British, turned Galata into a port of free-trade through their practice of capitulations. By 1855 Galata, and in particular Perşembe Pazarı, Voyvoda Street, and Karaköy, had developed into the main commercial center for European goods and banks; as a result, the Greek, Armenian, and Jewish citizens living in other districts of Istanbul started to gather in Galata, and thus the ethnic structure of the city changed once more. A new cosmopolitan type, referred to as the Levantine, emerged. This period also saw a concomitant rise in the construction of new churches and synagogues in Beyoğlu.

According to the 1927 census, 49 percent of the population in Galata and Beyoğlu consisted of Muslims, 21 of Greeks, 11 of Jews, 8 of Armenians, 6 of Catholics, and 2 of members of other Christian denominations. It was in Galata that modern urban development was first realized in Istanbul, a change resulting largely from pressure from the European inhabitants. Galata-Beyoğlu, the streets of which had previously been dark, muddy, and full of criminals and beggars, attained the status of European municipality in 1857. This period saw the creation of new sources of revenue and improvements in the standards of living. Both of these developments were implemented by the municipal council; the inner walls were demolished, wider streets were built, sanitation and lighting were improved, and a municipality control unit was established. The initiative among foreign residents to turn the municipal council into a completely autonomous administration, however, did not pass without conflict with the Ottoman government.

Transportation on the Golden Horn consisted mainly of boats traveling between Istanbul and Galata. The first bridge over the Golden Horn was built between Azepkapı and Unkapanı in 1836. 1876 saw the construction of a tunnel with a funicular that connected low-lying Karaköy to Beyoğlu above. At this date such a system was one of the first of its kind in the world.

FOOTNOTES

1 Three Years in Constantinople or Domestic Manners of the Turks, London: H. Colburn, 1845; A detailed description of Ottoman-Turkish arts.