INTRODUCTION

Located between two seas and across two continents, Istanbul served as the capital city to two long-lived empires. Despite its significant decline in prosperity during certain periods, from the Early Middle Ages to modern times, Istanbul has not only been a commercial and cultural hub, but the most crowded and cosmopolitan city in the Mediterranean region.

“No book stands a chance of fully conveying a city with all its formative elements;”1 this statement is particularly true if the city in question is Istanbul. Urban space is a dynamic formation in which patterns of multi-dimensional relationships take place over time. There is, of course, a yesterday, today, and tomorrow for every moment in which these interconnections take shape. That is to say, what is in question is a place that has been formed by the accumulation of present actors who base their conduct on past experiences and future expectations. Urban space, therefore, is a structure that is continuously becoming more intricate and stratified through the aggregation of experience from different eras.

While economic, political, and social formations shape the physical space of a city, it may take time for historical formations to do so. In other words, the rhythm of physical change is relatively slow and the physical structure of a city is more resistant to other types of conversions. One must keep in mind that the impact of economic and political forces on urban space remains for a long time and fuses with the next sets of impacts. Occasionally, these two sets collide, but most typically, economic and political forces pave the way for future urban formations. In the study of urban morphology, it becomes important to determine how the heritage of a certain period is assessed in later times and, indeed, how it has affected the urban environment. Inferences regarding elements that are inherently perpetual or having dimensions of conversion facilitate a clearer understanding of space.2

We need to reflect upon the multi-layered nature of the physical texture of a city like Istanbul, for such exercises uncover long historical periods. “[Different layers] that define places are like concentric layers, rather than sequentially following one upon another.” Within a certain period of time, in urban settings, there is in question a whole “formed by parts, not all from the same era and dependent on wholes that have actually collapsed or that no longer exist.” These parts are integrated through “fine-tuned” balances.3 And where there is “equilibrium” at stake, there is constant tension, conflict, as well as reconciliation. In stratification, a layer from a particular era does not get spread over another one as if it were a sheet. Rather, pieces from the preceding era will be appended with different values and meanings to the new one. Occasionally it so happens that such a piece is given a whole new meaning, and thus, a pivotal role in an ensuing era. Other pieces, however, may be ground into dust and added to the mortar to be used in the construction of entirely new structures, while remaining in the same space. What is referred to here is the grand whole of the past - a legend, a proverb, a long-standing tradition, a mode of behavior - that has percolated into the relationships found in patterns of space. As de Certeau put it, “Even the most insignificant and smallest sentence uttered in everyday speech walks in the same manner.” 4

The main purpose of this study is to try to explain the physical restructuring in the urban space of Ottoman Istanbul through power relations and economic and social processes. It examines the production of space based on an analysis of the relationships between the core components constituting its physical texture, rather than attempting to describe the physical texture of the urban space itself. Instead of questioning if these so-called imprints of the city have survived to the present day, this study traces key aspects of their development in an attempt to determine how urban imprints have been transferred throughout different periods over time. The reason for this is that these imprints are survived by the relationships and needs that occur in space.

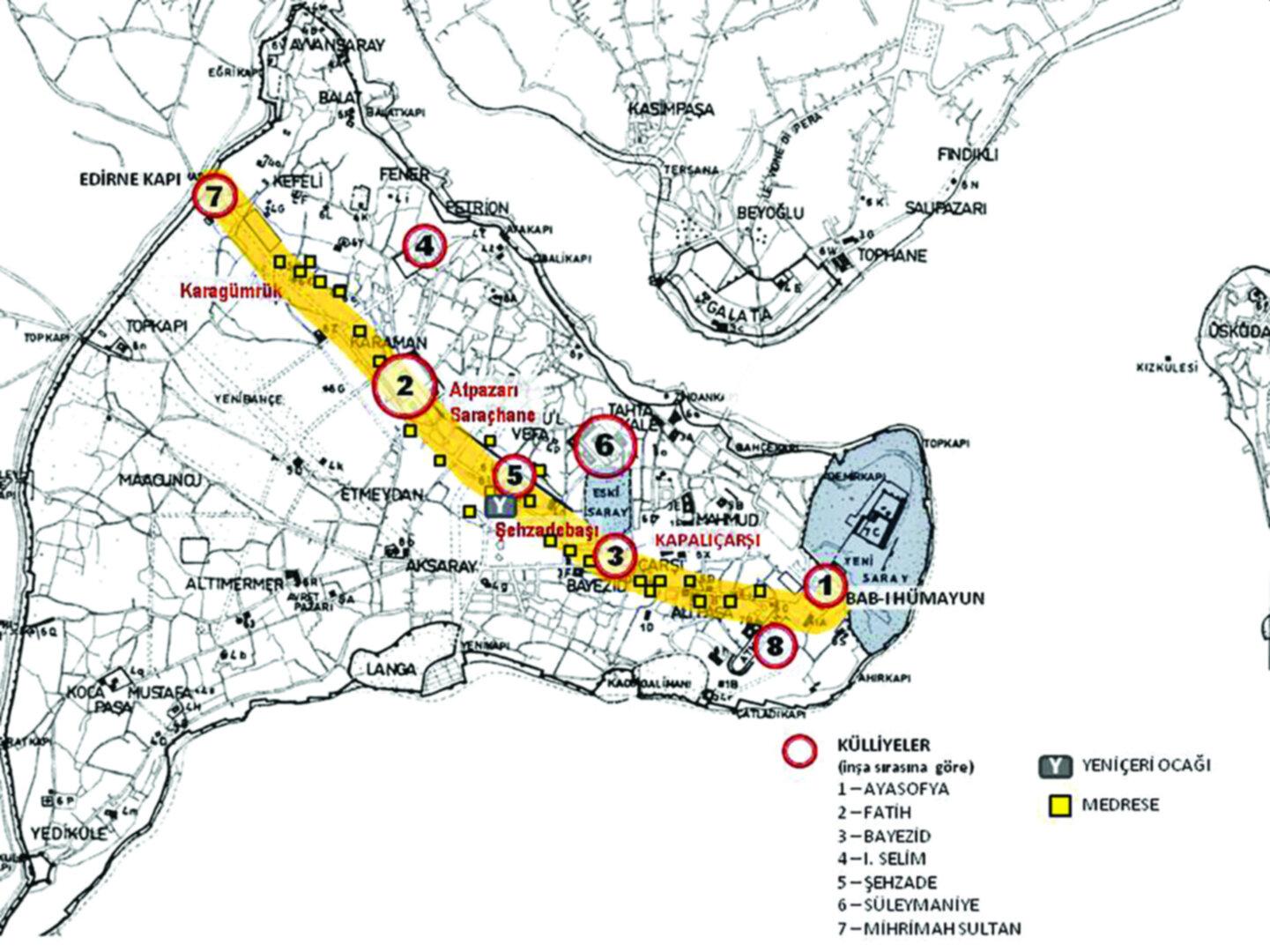

It is impossible to completely condense stratified cities, such as Istanbul and Rome, into a single narrative. This is especially true when scholars focus on long periods of time. Analyses that attempt to do so will eventually weave a fiction of some sort, with many of their explanations relying on assumptions. Addressing the morphological development of Ottoman Istanbul in its entirety brings about additional and specific challenges. First of all, in order for a multi-component structure to be resolved, many layers of data must be created. And, in order to determine exactly which changes have occurred in historical processes, it is necessary to provide counterparts in the form of data from time periods within the same or a similar categorical framework; this is a task that presently seems impossible. A more efficient method is to identify cross sections in this stratification so as to make inferences about the whole. In the current context, the following have been identified as revealing the integrated structure of Ottoman Istanbul within its overall outline: Istanbul’s physical location, its relationships with those geographical areas that have ensured the survival of the city and changes in the macro-form of the city. In the following section two main axes are examined enabling the reader to trace the five-century spatial development of the city. Accordingly, we are able to survey Istanbul in light of the aforementioned theoretical account. The first of these is the Grand Bazaar (Kapalıçarşı) - Golden Horn (Haliç) - Galata axis, which is a trade area in which production, distribution and commerce take place. This axis is the zone that feeds the city. The second axis is that of the Imperial Council Road (Divanyolu), which extends from Topkapi Palace through Beyazıt Square to Edirnekapı. This axis is an area in which power relations bear a particular weight, where the ruling elite makes itself visible and where daily life, shaped by cultural, educational, and commercial activities centered its own imprints on the above power,forms.

In the study of long periods of time, it is also necessary to carefully categorize the historical periods involved. Given Istanbul’s status as a former capital, we cannot expect its history to be independent of Ottoman political periods. Nevertheless, its demographic structure, economic bodies, construction and settlement activities, power relations and the constant presence of urban risks such as natural disasters and epidemics have each played major roles in defining different periods in the city’s history. The transformation phases of Istanbul’s urban space have been examined in five separate periods. The first phase is the establishment of Ottoman Istanbul (1453-1520); the second is the completion of an urban framework following the implementation of comprehensive projects (1520-1617); the third is the deterioration of this framework as a result of the city’s increasingly dense and complicated character (1618-1718); the fourth phase involves the search for new approaches in urban development (1718-1820s); and the last phase refers to the transformation of urban space shaped by administrative and economic changes in the 19th century. In the following sections, Istanbul’s development is examined in terms of space and not in light of these consecutive periods. In this examination, however, the general characteristics of these periods have proven to be decisive.

THE BOUNDARIES THAT CREATE ISTANBUL

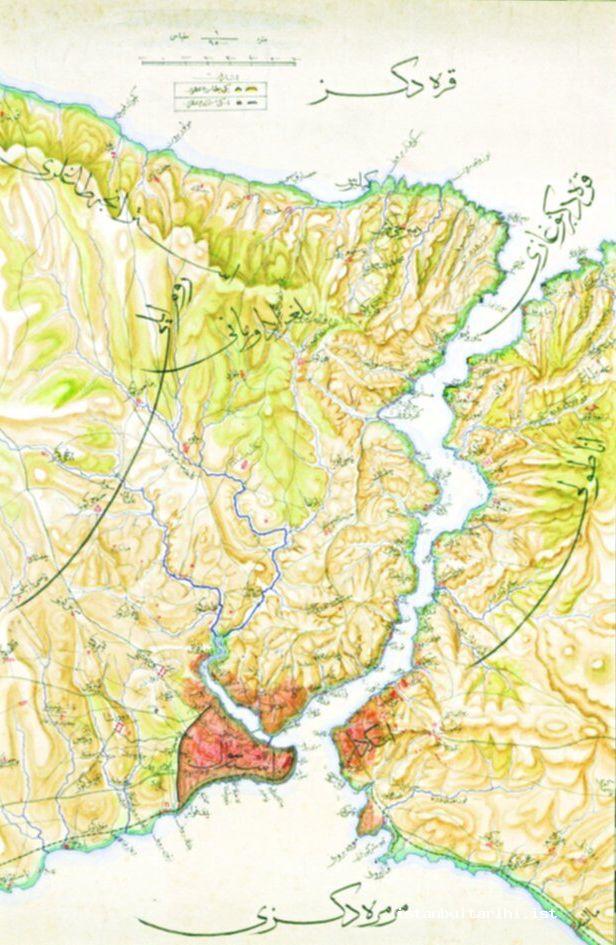

The reconstruction of Ottoman-era Istanbul took place on three different spatial scales. On the upper scale, efforts to establish and secure Istanbul’s long-distance land and sea connections, especially those with the Black Sea and the Aegean Sea were decisive; on the middle scale, the organization and re-population of rural areas within a daily distance from Istanbul were important for the city’s need for fresh produce; and, on the lower scale, the construction and settlement of the city itself were determinantal.

We might claim that works focusing on a regional and rural scale were given priority during the first ten-year phase following the city’s conquest. As Mehmet Genç makes clear, the development of hinterlands within reach by land transport could only raise Istanbul’s population by 40,000-50,000 people, given the technological conditions of the day. Maritime transport was a great advantage in expanding the city’s agricultural hinterland, so much so that the Byzantine Empire could survive in the century leading up to city’s conquest, despite being surrounded by Ottoman lands on both the European and Anatolian sides.5 Starting with Orhan Bey, Ottoman administrations developed strategies to control long-distance trade. With the conquest of Istanbul, the link between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean had to be established as well.6 When Mehmed II declared himself to be “the Sultan of the Two Lands and the Two Seas”, he was pointing to the Ottomans’ newfound status in the Mediterranean region. In the second half of the 15th century, the Ottomans began to take the Black and the Aegean Seas under their control. With the decline in Black Sea trade between 1350 and 1450, and the Ottomans holding sway over the same body of water, the Genoese abandoned the Black Sea, and the Venetians developed new strategies to maintain their foothold in the Eastern Mediterranean in response to growing Ottoman power.7 As Istanbul was readying itself to become one of the main power hubs of the Mediterranean region, it was also reorganizing the transportation and settlement networks of its land, which was expanding towards the Balkans and Anatolia. As such, economic and political balances were being re-established so that the Ottomans had full control of their networks.

The organization of Istanbul’s peripheral districts was of particular significance for feeding the city. Given the transportation and production conditions of the pre-modern era, perishable foods, such as dairy products, fresh fruit and vegetables, had to be delivered to consumers within a day or two. Due to transportation costs, fresh produce had to be supplied from gardens, orchards and farms either located right at the periphery of the city or in villages at a distance of a day’s journey (approximately 8-10 hours). During campaigns in the Balkans and Morea from 1458 to 1473, Greeks and Serbians were forced into exile; similarly, after battles against the Akkoyunlu Principality, the Turcoman tribes of Akçakoyunlu were exiled from the provinces of Tokat and Sivas. These displaced groups eventually resettled in the rural areas of Istanbul’s European side, where they established 180 sharecropping villages.8 It was in this manner that production sites for perishable foods were organized in Istanbul.

Because of its extraordinary geographical position, it is difficult to clearly determine the boundaries of Istanbul’s urban areas following the 16th century. Additionally, the exact geographical area of historic Istanbul is not always clear in key sources. For example, Istanbul on occasion refers only to the area inside the city walls, while at other times its boundaries include Galata, and even Üsküdar. The boundaries of urban life in old Istanbul - especially when daily transactions are considered –may extend as far as Tarabya and Yeniliman along the Bosphorus. Therefore, we should note from the start that studies dealing with the history of Istanbul have no consensus regarding where the city starts and ends. Settlement trends determined by the limits of maritime transport would eventually lead to the formation of a macro-form with a high level of rural-urban movement on the Bosphorus (later extending to the shores of the Marmara Sea). Of course, with transportation contingent on sailboats and rowboats, we cannot speak much of heavy traffic on routes and roads between Bosphorus settlements and the main city. Nevertheless, Istanbul elevated these small settlements to the status of township over the following centuries. The growth of these settlements may in fact reflect the importance of the Bosphorus in the daily lives of Istanbul residents, especially from the 17th century onward. Villages located along the shores of the Bosphorus were sites of waterfront mansions for members of the dynasty, statesmen and the wealthy. As summer resorts, excursion destinations, and recreation areas for urban people, these villages became townships over time. These Bosphorus settlements were also places where people took refuge from epidemics such as the plague and cholera, both of which frequently broke out in Istanbul. Additionally, these settlements also housed long-term residences for those displaced by fires in the city. Beşiktaş (in the 16th century), Ortaköy and Kuruçeşme (in the 17th century) and Bebek and Kandilli (in the 18th century) took on urban characteristics.9 The process in which Bebek became a residential area is characteristic of its era. When Sultan Ahmed III had the Hümayûnâbâd (Bebek) Pavillion built in 1725, he also constructed a bath, a mosque and a bazaar around it. The onshore mirî (state) lands were zoned for residences, some of which were reserved for statesmen, while others were sold to the public. The former residents of this area, mostly textile dyers, were forced to move out as a result. A similar development occurred on the opposite shore, in Kandilli. In the Kandilli Gardens, which were favored by Sultans Murad IV and Ahmed III, mansions and pavilions were erected; in 1748, the garden was parceled out as a residential area. Afterwards, government officials and notables of the palace took an interest in the area and the construction of a mosque, a church and a fountain behind the waterfront mansions fostered the growth of Kandilli over time. Soon after, the district began to expand along a newly built road that linked Kandili to a nearby village further inland.10 It should be pointed out that, although the process in which the mirî lands at the city’s periphery were put up for sale was known to have started with the Code of Lands in 1858, the early examples of this process took place in the 18th century.

The settlements of Rumelihisarı (Fortress of Rumelia) and Anadoluhisarı (Fortress of Anatolia) were originally built for defensive purposes, but by the 17th century they resembled townships; the numbers of households in both topped 1,000. By the end of the 18th century, settlements had emerged along the Bosphorus coastline from Beşiktaş to Rumelihisarı, all of which were connected to Istanbul by a land route. The opposing Anatolian coast, however, retained more of its natural character. Beyond Rumelihisarı and Anadoluhisarı, which were established at the narrowest stretch of the Bosphorus, settlements were sparser in the 16th and 17th centuries, though Yeniköy and Beykoz, stood out as “prosperous townships”. The full integration of such Bosphorus settlements with Istanbul came about in the 1850s with the introduction of regular ferry service.

The expansion of Istanbul’s urban boundaries will be addressed in line with the five historical phases outlined above. In the foundation phase that covered the second half of the 15th century, the city appears to have been confined by its former Byzantine borders. The only case in which these boundaries were exceeded was in the establishment of the Eyüp neighborhood on the shores of the Golden Horn. Two questions regarding the building process of Istanbul following 1453 are particularly suggestive when posed in tandem. First, can the post-conquest development and growth process of Istanbul be explained through the ‘multifocal urban growth model’ observed in the period of Anatolian principalities? Secondly, we should ask whether the Ottoman capital of Istanbul was built over traces of Byzantine Constantinople.

As in Bursa and Edirne, the first step in Istanbul’s multifocal urban growth model was the construction of a commercial hub in order to form a new city center located outside of the Byzantine city walls. This center included a mosque, a market place and a bazaar, and officials expected growth to spread outwards from this new urban hub. The second step involved the construction of a number of residential areas at certain distances from both the new city center and each other. Built around religious complexes or mosques, these were to become the focal points around which neighborhoods would develop. Over time, growth from the new city center converged with growth from these new neighborhood centers, forming an integrated urban environment.11

The Ottomans found Istanbul to be a different city from those they had settled in before. In 1453, the city was a dysfunctional and worn-out version of Justinian’s Constantinople. The Byzantines had spent their last century in the city living in a ruralized environment, as it were; the city was in a ruined state compared to its glory 700 years before. Magdalino points out that the city began to gradually crumble away following the Latin invasion of 1203 and the great fire. The urban area became concentrated in a few distinct quarters inside the city walls throughout the 14th century. One of these was a piece of land in the northwest comprised of large monasteries surrounding the Blachernae Palace, while another consisted of Hagia Sophia and a number of monasteries in its direct vicinity. The city’s commercial district was located in-between these two areas, stretching all along the Golden Horn.12 Sources estimate that around 70,000 people lived inside the city walls at the turn of the 15th century, which is notable in comparison to the 400,000 –500,000 people that had once resided in a similar area.13 Nonetheless, the city still bore millennium-old traces of its time spent as capital of the East Roman Empire, no matter how dilapidated it may have become. The Ottomans endeavored to reconcile their own settlement practices with the city’s given condition. At the point of conquest, the area encircled by the city walls was so large that officials would not feel the need to expand urban boundaries for a long time to come. The Ottoman construction process at the time, then, cannot be likened to an attempt “to found a new Ottoman city around the Byzantine kastron,” but rather it must be seen as the “reconstruction of a thousand-year-old capital.” This building process will be discussed in detail in the next section.

Although the city walls were not needed for security purposes during the Ottoman era, ruling officials made sure that they remained intact. Apart from the repair work done immediately following the conquest, the walls underwent their most systematic repair after the city sustained major damage in the earthquake of 1509. In the 17th century, large-scale repairs were carried out by Governor Bayram Pasha and in the 18th century by Damad İbrahim Pasha.14 New gates were opened in the 19th century, especially along the Golden Horn. An association had developed between the city of Istanbul and its powerful walls throughout history, which caused the Ottomans to view them as a symbolic indicator of their power. Another reason for the city to maintain their structure was that the walls delineated its boundaries. Narratives of Istanbul from the 17th and 18th centuries mention gates in the walls, with scaffolding in front of them, as coordinate points in the city. Reading between the lines, we understand that the walls fulfilled purposes of control even as the city outgrew them. Remaining inside the walls meant keeping the city under control. A warning given by the Ottoman administration to the embassies settled in Pera serves as an example of this. In 1612, the grand vizier of the time threatened all of the embassies to move inside the city walls; this demonstrated that the location of these embassies, in the district of Pera outside of the walls, was far from Ottoman leverage and that this distance was being abused by foreign officials.15

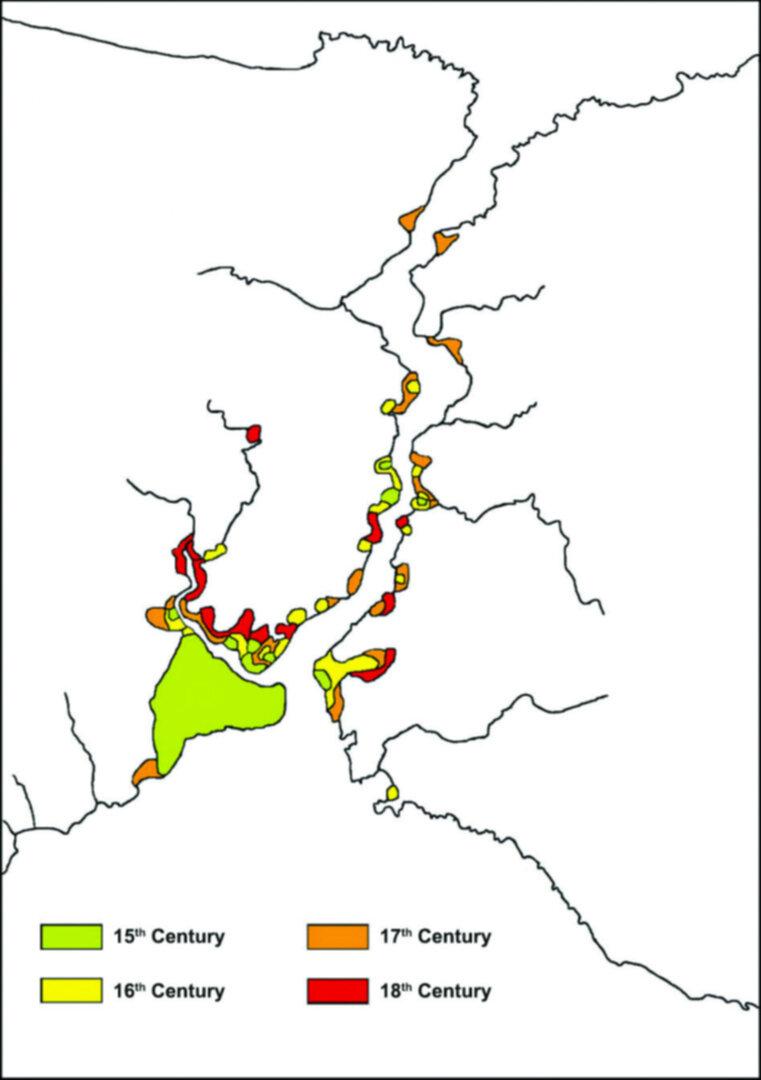

The only protrusions outside of the city walls in the 15th century were the neighborhoods of Eyüp and Tophane; the latter was located just outside Galata. Scholars estimate that the city’s population reached 100,000 in the late 15th century. In the 16th century, Galata came to be surrounded with the construction of the Royal Shipyard on the Golden Horn, the reconstruction of Tophane, as well as the development of a number of masjids and mosques on the coast. Beşiktaş grew into a township, while Üsküdar flourished and began to extend eastward. Also around this time, Suriçi (as the area inside the walls was called) became more densely populated and the organization of services improved with the construction of comprehensive complexes (külliye). Following the construction of these complexes in inland districts of the peninsula and the conversion of some churches into mosques, the Christian community began to move to the shores of the Golden Horn. According to some estimates, Istanbul’s population was 250,000 around the end of the 16th century, and close to 400,000 around the 17th century.16 This being the case, we understand that the population of the city had risen considerably by the 17th century, which in turn may explain the increasing number of fires and epidemics at this time. Both sides of the Golden Horn had begun to fill up and waterfront mansions were now being built in the vicinity of Kâğıthane. (Fig. 1)

In the 18th century, an era regarded as a new phase in Ottoman society, a new trend emerged in the development of pre-established quarters of the city. The provision of new residential areas arrived as officials developed coastal areas within city boundaries, demolished certain segments of the city walls and sold pieces of land that formerly housed palaces to the public. The Langa Harbor in Yenikapı (formerly known as the Port of Theodosius) was filled in 1764, and plots in this area were sold to Armenians, who helped to establish the new neighborhood of Yenikapı. An old palace previously assigned as a residence for heirs apparent was pulled down and the plot was sold to Armenians and Greeks; a marketplace formed on this site in the following years. And again, in 1801, land that formerly belonged to the Galata Palace was sold “at a high price,” and was eventually turned into a residential area complete with gardens.17 It may be inferred that these income-generating enterprises, undertaken upon orders of Selim III, capitalized on the excessive rise in land prices. We learn from Evliya Çelebi that the area inside the Galata walls was completely inhabited in the 17th century, and from İnciciyan that the density of the buildings on the coastline increased from the beginning of the 18th century. Additionally, patches of land along the coastline were fully integrated into waterfront property in order to gain more building space. During this period, permission was granted to those who wished to build over dilapidated city walls or on plots of land that could be obtained through clearing away such walls. A more extensive demolition of the walls took place in 1864 with an operation handled by the 6th Municipal District and new plots were put up for sale as a result.18 This trend must be interpreted as a short-term solution to seek more space within the city’s boundaries, which had outgrown the walls. If we remember the settlement process of Bebek and Kandilli mentioned above, the new settlement trends of the 18th century were solutions towards finding plots which would further increase the city’s housing capacity. In fact the inhabited area actually shrunk, owing to limited transportation services which were not quite conducive to the city’s desire to grow beyond its boundaries. But, interestingly, sultans of the period did not hesitate to part with property that belonged to the palace. In the 19th century, the urban macro-form was to undergo a radical transformation with the introduction of new transportation technologies and legal regulations.

THE TWO MAIN AXES OF ISTANBUL’S TOPOGRAPHY

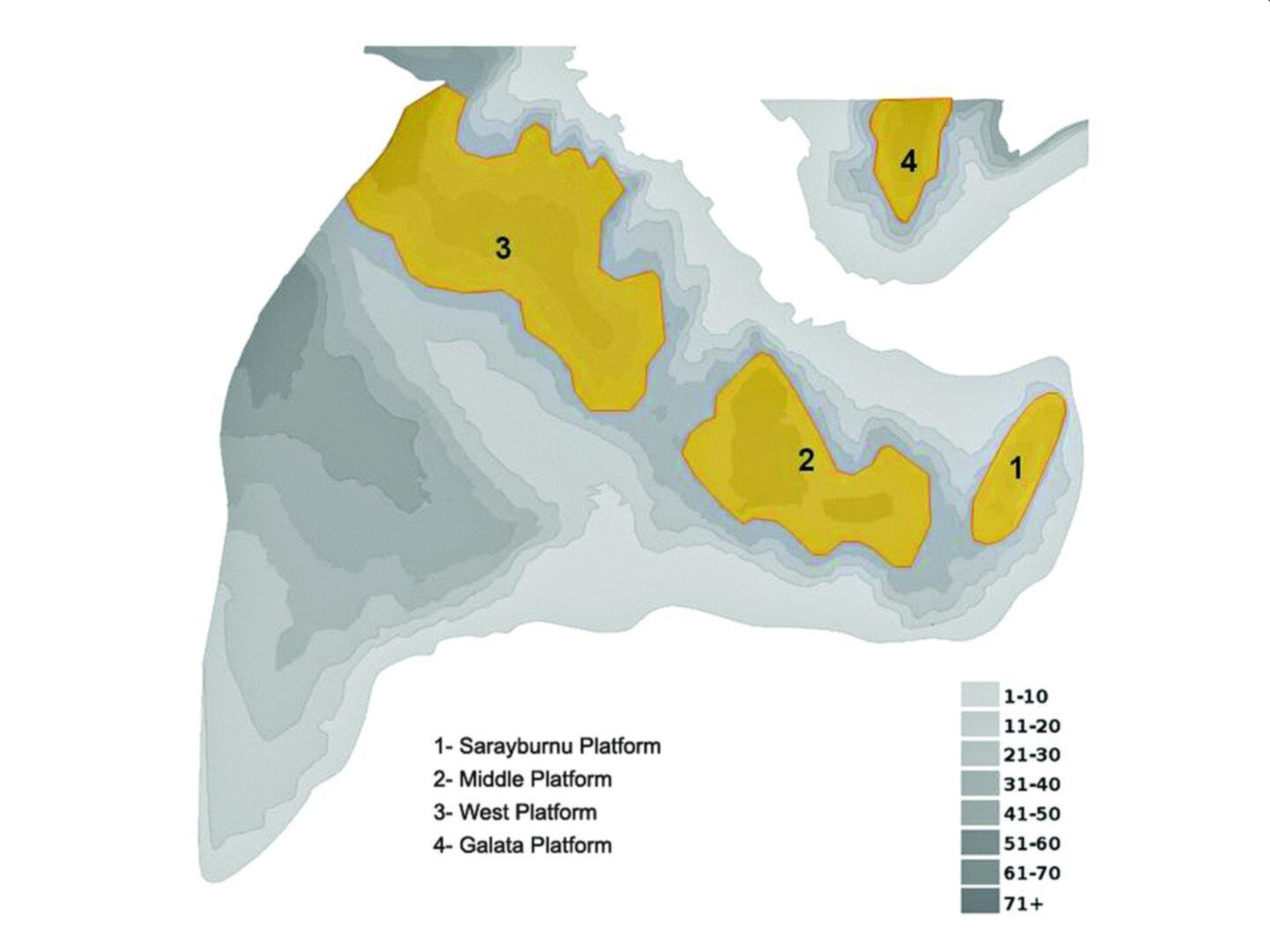

The key elements of Istanbul’s topography are the Golden Horn and the nearby hills that offer an uninterrupted view of it. There are three prominent platforms on the northeast-southwest axis, including Atmeydanı (Hippodrome), Hagia Sophia and Topkapı Palace (The Grand Seraglio) inside the walls and on the southeast-northwest axis that extends from Beyazıt Complex to Fatih Complex and up to Edirnekapı. Six of Istanbul’s “Seven Hills” can be seen clearly from this platform. We can refer to the first of these as the “Seraglio Platform,” the second as the “Middle Platform” (where the Old Palace and Covered Bazaar were established), and the third as the “Western Platform” (the axis of Edirne Gate and the Fatih Complex) (Fig. 2). On an Istanbul map by Kauffer and Lechevalier from 1786, it is noteworthy that the elevations that surround the Golden Horn are indicated particularly clearly. (Fig. 3)

Seraglio Point is strategically located owing to its position overlooking the Marmara Sea, the Bosphorus and the Golden Horn. This district, which was home to the acropolis of Ancient Byzantium, was located away from the bustle of the city. The middle platform is also effectively located because it possesses the most accessible axis between the Golden Horn and Kadırga Port. The intersection of this north-south axis, with an axis that extends from Edirnekapı to Hagia Sophia, further strengthens the strategic position of the middle platform. Although the exact locations of the harbors have changed over the years, high levels of accessibility have ensured that trade areas have been located at this point through the ages. The most important feature of the western platform is its location, particularly because it welcomes incoming traffic to the city from the west through Edirne Gate. Yet another of its advantages is that it contained important water sources; two cisterns from the Byzantine era are located in the area. According to Magdalino, the city took on a rural look during the Byzantine Empire’s final centuries. In the northwestern districts especially, the “proximity to fresh water” was a major reason for their dense concentrations of residents, palaces and monasteries.19 Galata, itself another elevation on the other side of the Golden Horn, offers an uninterrupted view of all of the topographical elevations inside the city walls. In numerous engravings of Istanbul from the 15th and 16th centuries, the spectacular silhouette of the city emerged for a “watching” Galata.

Trade Axis

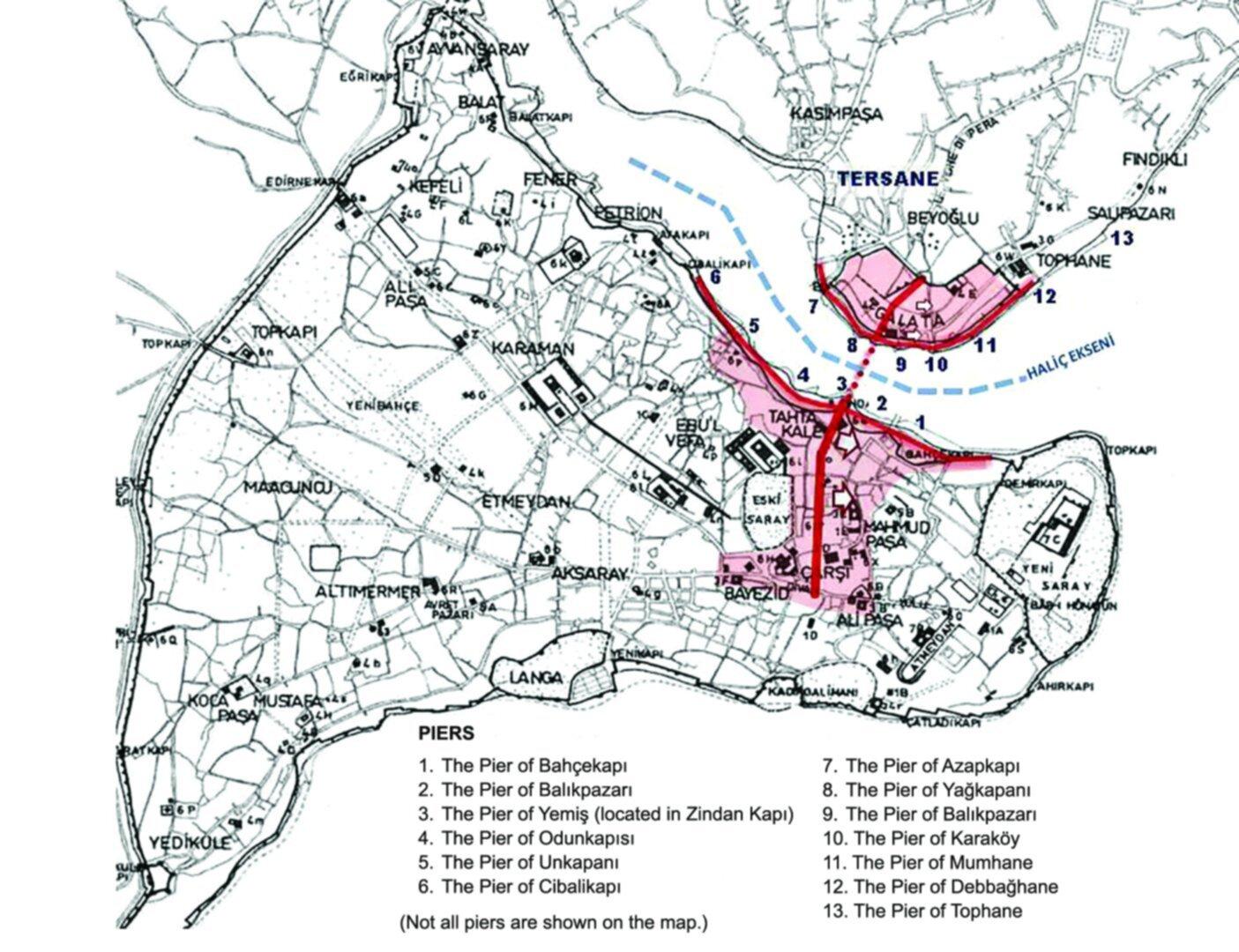

The Golden Horn is a natural harbor that integrates Istanbul into maritime trade. This natural harbor is also one of the main channels determining the city’s macro-form. Additionally, the land route that links the Balkans to the city (despite not being a trade axis in its entirety) terminates at the Grand Bazaar by way of Divanyolu axis. The sea and land axes that establish the external links of the city have an eastern and a western direction, and they further combine with another axis that runs in a north-south direction. Having formed the backbone of trade and production activities throughout the Ottoman period, this axis brings together the Grand Bazaar, the Golden Horn and the Galata Tower. The footprints left on the urban fabric by the main part of the urban area, of course, do not follow a single-street route and the density of these footprints varies depending on time and the relationships formed in its passage. Just as the most congested route so often moved from one street to another, increasing and ramifying popular routes over time, there were also streets that became less and less crowded, losing their significance as years passed. However, what should be emphasized here is that the direction of the main stream and the overall pattern of the urban fabric did not change. The trade network that formed around these three main axes, drawn in order to optimally define the trade district, demonstrates that the area inside the city walls, alongside the Galata district, was a wholly coherent structure.

Those who concentrate their research on Istanbul’s commercial area, or any particular aspect of this district, concur that following their inheritance from Byzantium, the trade axes showed continuity into the Ottoman period.20According to Magdalino, whose research focused on Istanbul’s medieval age, “the commercial importance of the Grand Bazaar quarters of Sirkeci, Eminönü and Tahtakale along the Golden Horn dates back as far as the early Byzantine period.” He also contends that Galata’s existence, with its European identity and subsequent rise, “dates back to 1261, when the Byzantines gave Pera to the Genoese.”21 We might add that Genoese Galata emerged mainly through settlement processes in the 14th century. While the late Byzantine commercial activities of the city were undertaken by the two Latin colonies that had settled on both shores of the Golden Horn, the integration between the north-south axes took place during Ottoman rule22 in the 16th century. Mortan and Küçükerman also point out that “an economic area consisting of the Grand Bazaar, and the Mahmut Pasha Commercial Building and the Galata Bazaar which were built at later dates, must be viewed as parts of a whole.”23 The role of continuity in functional and property relations, which may be observed in the physical fabric of the city, should be noted.

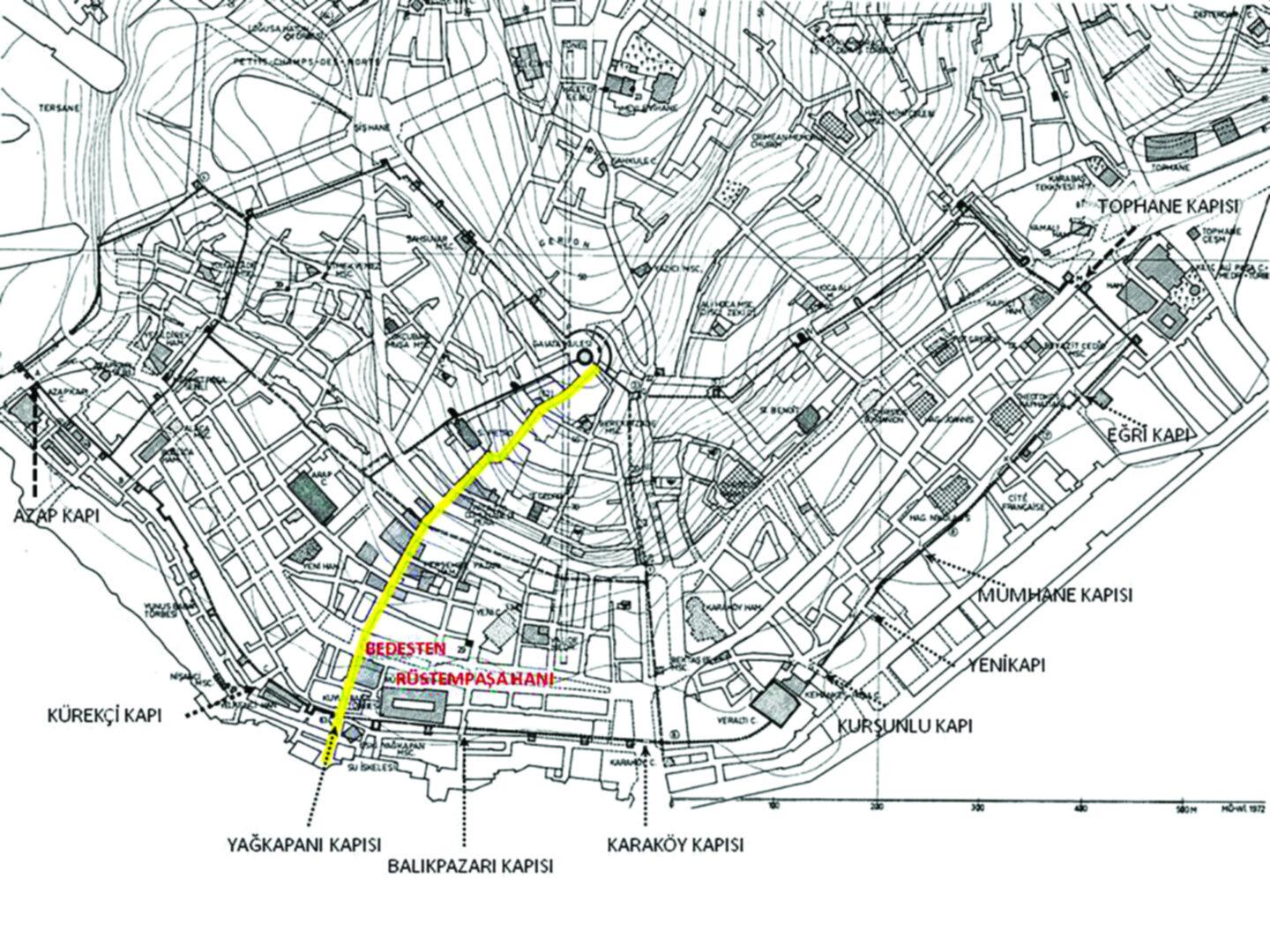

The north-south axis traverses an uninterrupted route between the Grand Bazaar, the Golden Horn and the Galata Tower. Moreover, there is evidence suggesting that this axis extends as far as the Kadırga (Iulianos) Harbor in a southward direction on the shores of the Marmara Sea.24 This route starts from Divanyolu, progresses along Uzunçarşı (Makros Embolos25 or Marianos Embolos26), from which it exits through Zindan Gate (Dungeon Gate), eventually leading to the Zindankapı Wharf. The distance between here and Yağkapanı Port (Porta Comego) on the opposite shore is the shortest in all the Golden Horn. The line in question must have been the first choice of boatmen who would row between the two shores until the Haliç Bridges were constructed in 1836 and 1854 respectively.27 Upon entering Galata through Yağkapanı Gate, one could reach the Galata Tower from Perşembepazarı Street. The axis of the Grand Bazaar-Golden Horn-Galata, then, is the sum of the shortest distances both on land and sea. (Fig. 5) At a time when commercial traffic was totally dependent on manpower, it is only natural that such a route would develop; pedestrian access was within tolerable limits, e.g., the route was at a slope of only 5 degrees.

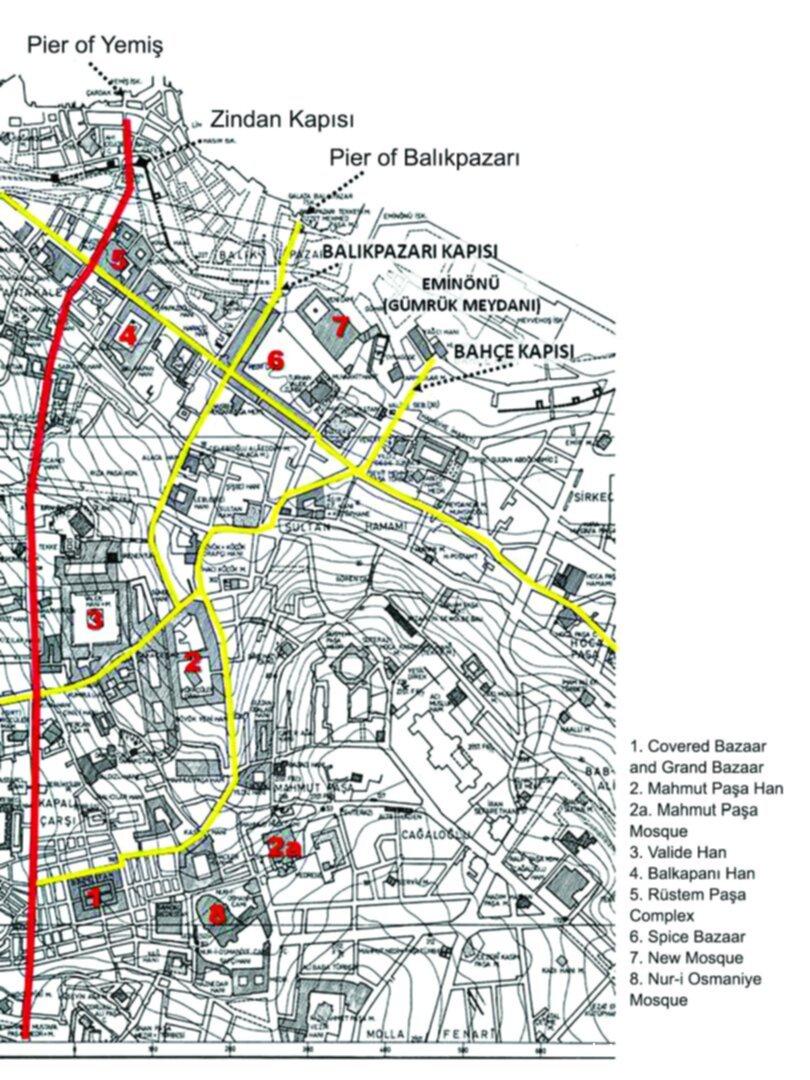

Toward the end of the 16th century, the Suriçi trade area was delineated in the south by the Beyazıt Complex and Divanyolu; in the east, it was delineated by a line that culminates in Eminönü by way of the Cağaloğlu and Babıali Slopes.28 In the west, the line starts from Beyazıt Square, follows the eastern wall of the Old Palace, eventually reaching Odun Gate, covering the Süleymaniye Complex on its way. The heaviest traffic in this patch, however, is in Uzunçarşı, which is the most important part of the north-south axis. In total, the Suriçi trade area was structured around five main foci, which were lined up from the shores of the Golden Horn to Divanyolu. These axes included the following areas: the vicinity of Tahtakale and Zindan Gates, the Spice Bazaar (Mısır Çarşısı), the Mahmud Pasha Commercial Building, the Valide Sultan Commercial Building, the Grand Bazaar and the Bazaar of Book Dealers (Sahaflar Çarşısı), whose core was formed by covered bazaars (bedesten).29

No matter which spatial scale is used, trade in Istanbul is often explained through the “meeting of land and sea”30; the Golden Horn is the actual locus of such a pairing. Two basic elements of the city’s sea and land links were the pier and the fortress gate behind it. The biggest indicator of the association between these two urban elements is that they are, in fact, usually given the same name. Steps which began on the pier passed through the fortress gate and then led to the street. From here, one was led toward the inner city and onwards to the heart of different neighborhoods.

An area of flat lands toward the southern end of the Golden Horn, from Bahçe Gate to the Unkapanı Gate, is a district which to this day buzzes with commercial activity. Included in this district were customs officials (gümrük emini) in charge of maritime trade in Eminönü, Unkapanı, and Balkapanı (Yağkapanı on the opposite shore), and other customs officials (pençik emini). In the years leading up to the conquest of Constantinople, one of the rare settled districts was in fact this commercial area, which occupied the shores of the Golden Horn.31 Two factors testify to the superiority of this district in terms of building stock: not only were many houses and shops placed under the Hagia Sophia Pious Endowment (waqf) following the conquest32, but Mehmed II settled his own slaves on the shores of the Golden Horn.33As a historical paradox, Latin merchants, the Venetians in particular, played a major role in the survival of this district.

Venetians were granted customs privileges in 1082 and soon allocated properties near Bahçe Gate.34 They expanded their territory along the southern shore of the Golden Horn during the Latin invasion of 1204 - 1261. Although they were thrown completely out of the walls in the aftermath of the invasion, they were allocated an area that they referred to as “Locus Venetorum” in 1277.35 The fact that this colony chose to settle around Makros Embolos must have been due to the high number of piers they required, not to mention their preference of an area with easy access to all of the occupational specializations they would soon require.36 With a population close to10,000, Locus Venetorum resembled a small Republic of Venice in Constantinople.37 Within this settlement, the Balkapanı Commercial Building was one of the few commercial structures with records in the Ottoman archives that can be traced to the Byzantine era. The remains of walls in the basement, alongside certain architectural elements, offer significant evidence that the structure is in fact Byzantine in origin. As stated by Ağır, “A fondaco built by the Venetians in 1220 [...] is likely related to the Balkapanı Commercial Building.”38

According to a treaty signed on April 18, 1454, the Venetians were granted a palace and a church in the south of the Golden Horn that did not actually belong to them. The Venetian presence in the city faded after 1463, owing to changes in the political relationship between the Ottomans and Venetians.39 In 1492, the Venetian settlement disappeared completely40 following the confiscation of all Venetian property in the wake of the bailo being deported. However, the exact date of the Venetian bailo’s abandonment of the south of the Golden Horn is still a matter of controversy.41 Although the location of his winter residence is not certain, it is known that he had a summer residence built in the first half of the 16th century in what was called “Vigne di Pera” (Karşıyaka Vineyard), to the north of the Galata walls. Among the reasons why this location was selected were its cool temperatures, safety against the plague, and seclusion from Ottoman inspections; this last aspect in particular allowed political activities such as “helping runaway slaves and similar people to escape out of the country” to be carried out with greater ease. Following the conquest of Cyprus (1571), this summer resort became the bailo’s sole residence.42 In spite of the political turmoil between the two states, Venetian ties to the Ottoman Empire, and thus, to Istanbul, lasted until the 1630s.43

Based on a document which dates from 1513, the majority of new settlers in the Golden Horn’s southern districts were of Jewish origin.44 The place-names in the district demonstrate how well-established they were in this area leading up to the 17th century. Districts with dense Jewish populations included the neighborhood of Edirne and the neighborhoods around the Jewish Gate (Yahudi Kapısı), and districts between Tahtakale, the Egyptian Bazaar, Eminönü, and Mahmutpaşa.45 It is likely that this demographic settled in these areas because of their commercial skills; Jewish merchants, who mostly dealt in brokering in the second half of the 16th century, eventually came to rival the Venetians commercially.46

Even though the city’s commercial districts, which were mostly concentrated around the docks, were seriously damaged by fires and earthquakes, they did not depreciate in value as a result. In fact, rents from shops, commercial buildings and houses comprised a large portion of income for the Waqf of the Hagia Sophia Complex.47 The Byzantines and the Venetians also channeled their income from commercial areas through pious endowments for the foundation and maintenance of urban services.48

Structures such as the Balkapanı Commercial Building in the city’s trade districts, though rarely able to survive earthquakes and fires, testify to the continuity of the urban fabric over millennia. According to Berger, traces of Tahtakale Street go back to the 5th century. Kutucular Street and Hasırcılar Street are similarly historic.49 Rather than interfering in these established street patterns, city officials decided to build on pedestrian passages that had their origins along ancient trails. (Fig. 6) It is also understood that street patterns were the dominant factor in the development plans for the Mahmut Paşa Complex, which, upon construction, was the second largest market after the Grand Bazaar in the last quarter of the 15th century. Additionally,_two sections of the Spice Bazaar are located on two ancient axes,50 resulting in one of the finest examples of adapting a present building to fit the traces of historical commerce. (Fig. 7)

The second major hub in the formation of Istanbul’s trade district is the marketplace that developed around the covered bazaar. Magdalino makes an important point when stating that trade between the Kadırga Port and the Golden Horn became more intense and that urban land use might have intensified due to construction activities in the development that took place in Constantinople from the Middle Ages until the Latin invasion in 1203. One 10th century source, for example, points to the eastern end of Mese as the center of retail trade: we learn that “silversmiths were located in the district between the Constantinos Forum and Milion” and that they were selling high-quality merchandise at this location.51 These observations indicate that there are similarities between the Byzantine and Ottoman commercial hubs, the latter of which started to take shape in the 15th century and was formatively completed in the 16th century. The area deemed fit for trade by 10th century silversmiths was a spot close to the location of the Cevahir Covered Bazaar, where there was a concentrated population of jewelers during the Ottoman era. It is remarkable to note that a different cultural and political entity built a commercial center on the very same piece of land where their predecessors had built a center nearly 250 years earlier in 1203; the Ottomans thus revived an abandoned piece of land by restoring it to its former commercial function. The covered bazaar that was to form the core of the Grand Bazaar was founded as one of the starting points for the city’s reconstruction, between Divanyolu and the north-south axis; in a sense, it occupied the site between the city’s “prestige axis” and its trade axis. This decision hints at Mehmed II’s expectations for Istanbul. While he was strenuously endeavoring to populate the city, he was also continuing to organize its trade districts. Assessing the foundations of the capital’s economic history, Genç notes that construction activities were the main factor that stimulated Istanbul’s economy. Above all, construction created significant employment opportunities for laborers in so-called sub-sectors. In parallel with the creation of labor opportunities, the city’s consumption demands rose, giving further vitality to major economic sectors.52 Nevertheless, the creation of a bazaar must be viewed in contexts which extend beyond the activities and urban center in question. Through the 14th century, there had been a trade network centered on the city of Bursa which continued to develop and organize around Rumelia and Anatolia. By moving the heart of this network to Istanbul and by further strengthening the volume of trade through sea connections, the long-distance trade network that Ottoman officials desired was set in motion.

From a social vantage point, the shores of the Golden Horn were points of transportation for goods and people. Apart from heavy human traffic, incoming goods were unloaded, classified, stored, and distributed (particularly for feeding the city) here. There was also a concentration of commercial buildings accommodating wholesalers, market places, and customhouses. As one advanced toward the Grand Bazaar from the shores of the Golden Horn, streets became lined with shops peddling merchandise which, though light in weight, was heavy in value. The center of the four nested rings was the location of the most valuable commodities. More than a mere trade area, the Grand Bazaar was also an area of production. It was here that the production of expensive goods and fine crafts were made, often with intensive labor. The covered bazaar is the inner core of the Grand Bazaar, and it took on the task of banking. The second “ring” extending outward from the inner core contained jewelers; according to one source, it was here that “gold dust flies in the air.” In the third circle, elaborate stone, wood and leather products were manufactured. The design-manufacture relationship in production was established between the palace’s “community of craftsmen” (ehl-i hiref) and the artisans of the Grand Bazaar. Fashion in Istanbul, which spread from the capital to the provinces, was also determined to a large extent within this environment.53

With the addition of new arcade shops at the end of the 15th century, the city’s trade area became complete. Among the commercial structures commissioned by officials in the 16th century, a commercial building, a covered bazaar and a market place built by Rüstem Pasha on both shores of the Golden Horn are particularly noteworthy. The locations selected for these buildings, as well as their architectural structures, reflect the commercial entrepreneurship of Rüstem Pasha. The Rüstem Pasha Complex, for instance, consists of a mosque, a market place and two commercial buildings; its mosque was built at a point where Uzunçarşı intersects with Hasırcılar Street. The complex was constructed upon a plot of land believed to have formerly housed the Venetian St. Akindinos Church and the Hacı Halil Mosque, an early Conqueror-era structure. A rare example of Ottoman architecture, the structure has its mosque upstairs, while the ground floor was used as a bazaar.54 On the Perşembepazarı Street - the Galata extension of the same trade axis - the Galata Covered Bazaar and a caravansary were constructed. Built in the 1550s, these structures belonged to an era in which the city’s ruling elites began to get involved in commercial life, although most people frowned upon this development. With the addition of people from different administrative layers to the “entrepreneur grand viziers”, there came about a complicated network in which economic, political, and social ties became intertwined in the 17th century.55 In general, this century saw the urban fabric grow more complicated and worn out.

In the 17th century, comprehensive trade structures were built. These included the Buyer Valide (Grand Mother) Commercial Building (1640) between the Mahmud Pasha Commercial Building and the Golden Horn, and the Spice Bazaar, which belonged to the Waqf of the New Mosque. Considering as well a commercial building commissioned by Fazıl Ahmed Pasha, the investments made in commercial structures began to draw attention in this period. This increase may be considered as a development concomitant to Istanbul’s rising population. At the same time, however, commercial buildings and bazaars were being constructed throughout Anatolia. Faroqhi notes that the number of commercial buildings in Cairo also saw a significant increase in the same period.56 However, apart from the 17th century’s general economic downturn, a new economic organization was originating in parallel to the establishment of the Dutch Union, the shifting of production to rural areas and the Venetian merchants’ support of rural production and trade. The extension to Istanbul and Iran of the Amsterdam-oriented land-route trade,57 including developments in Central Europe and the Balkans, must have affected the commercial life of Istanbul and other Ottoman cities. The urban effects of this process have not yet been scrutinized at a sufficient level.

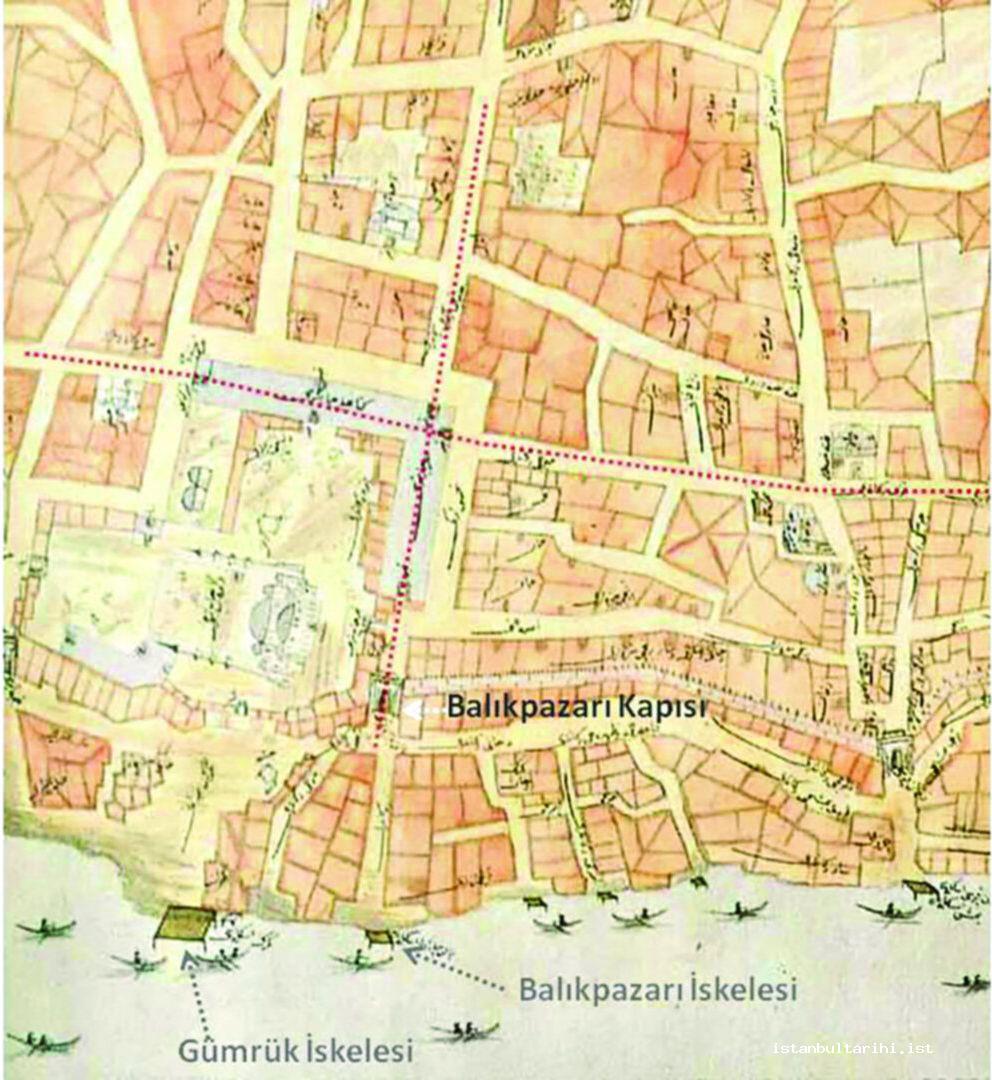

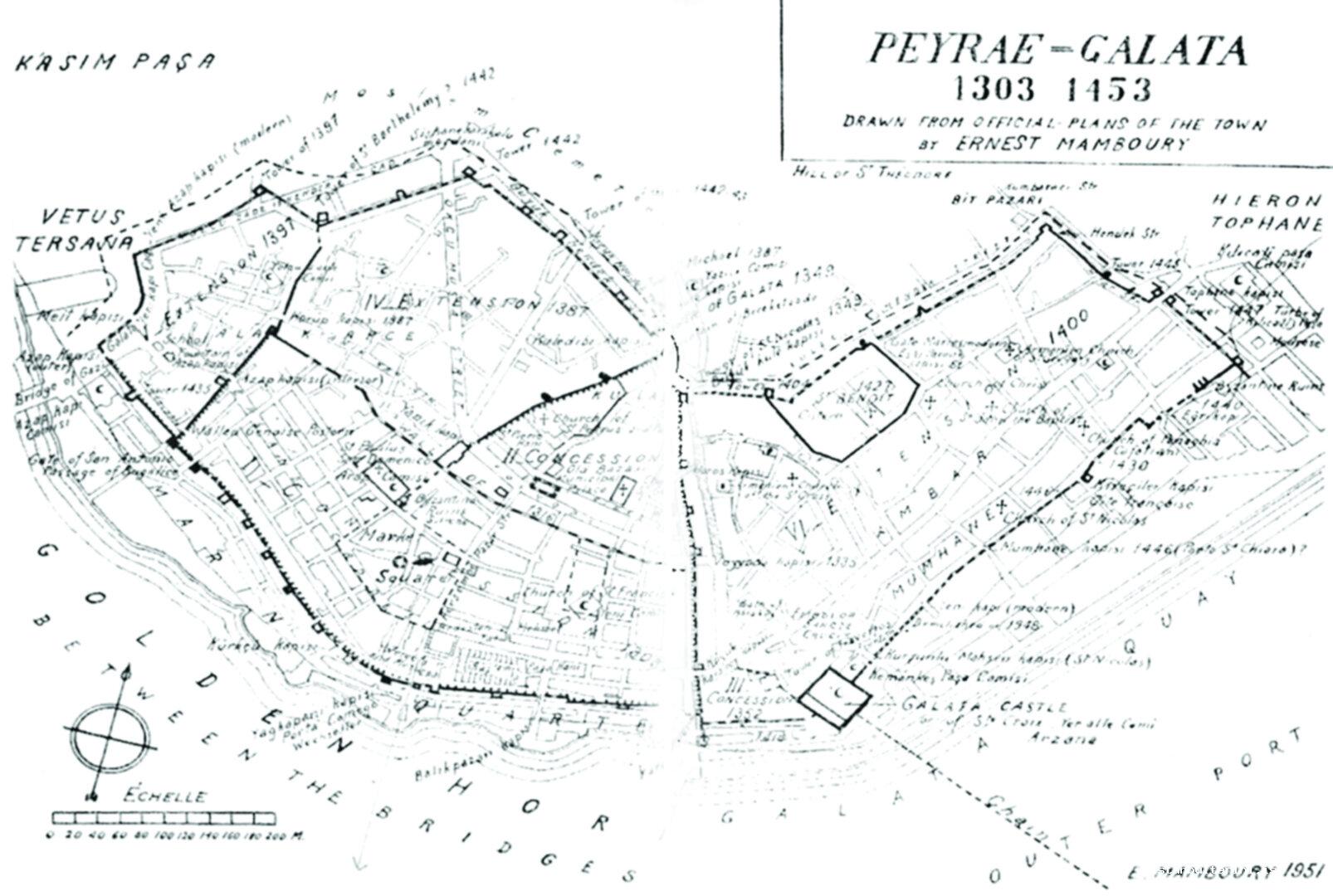

When we cross over to the opposite shore of the Golden Horn, a port of historical significance is the Yağkapanı Port; that the Galata customhouse was located at the Yağkapanı Gate until 167658 emphasizes its importance. The Galata route of the axis passes right through the middle of the first Galata settlement. According to a map drawn by Mamboury in 1951 (Fig. 8), it is possible that a Genoese square, typical of medieval towns, was on the same axis.59 Toward the end of the 15th century, important buildings on Perşembepazarı Street in a south-north direction were the San Michelle Church60, the Palazzo Communale (the mansion of the Galata voivode)61 and San Pietro Church. Situated nearby were the Galata Court and the Kalyoncu Sub-unit of Janissary Corps (Kalyoncu Kulluğu). It is also believed that the San Paolo Church (Arab Mosque), built in the 13th century by Dominicans who settled to the west of the route in question, might have been erected in place of a Byzantine-era church.62 This shows that the first nucleus of Galata could have been in this vicinity. In the second half of the 16th century, Rüstem Pasha constructed both a commercial building in the place of San Michelle Church for his waqf and the Galata Covered Bazaar on Perşembepazarı Street, to the west of the commercial building. İnalcık states that Galata housed the main warehouse of Aegean-based products such as olive oil and wine in the 15th century, and points out that “the work life was concentrated on the Perşembepazarı Street, also called Orta Hisar, in the Ottoman era, just as it was during the Genoese period.”63 (Fig. 9)

Many Mediterranean merchant ships would anchor at the Galata’s piers. The production and sale of oars, sailcloth, wax and crackers – all necessary items in maritime logistics - were therefore sold with increasing presence around the pier and shipyards. Naturally, ship maintenance and repair workshops were also located in the area.64

Over time, the main trade axis of the Grand Bazaar-Golden Horn-Galata shifted toward the mouth of the Golden Horn. After the 17th century, the route connecting the Grand Bazaar, the Mahmud Pasha Commercial Building, Spice Bazaar (Balıkpazarı [Fish Market] Gate)/Eminönü, Karaköy, Galata Tower, Pera took precedence over and replaced the straight line between the Grand Bazaar, Uzunçarşı, Zindankapı Pier, Yağkapanı Pier, Perşembepazarı, and the Galata Tower. (Fig. 5)

Even though economic and political conditions change throughout the centuries, the location of a commercial center in a city may remain the same. The reason for this is that its location remains engraved in the footprints determined by a universal commercial mindset. In the Byzantine era, cities within cities formed over this commercial axis. Although traces of this structure remained, the axis was integrated into its surroundings in stages during the Ottoman period. Although both the southernmost and northernmost tips of this axis represented different “poles”- such as Ottoman and European, and Muslim and non-Muslim- the trade area, as part of this integration, proved conducive to the unification of such cultural opposites. In other words, the district’s commercial ambience brought together elements of society which were normally opposed to one another. Instances of such cultural unification promoted the emergence of opposites coming together in a collaborative atmosphere. It was very difficult for foreign tradesmen to figure out the city’s complicated commercial networks - networks of different ethnic, religious, vocational groups and unions that, together gave rise to various partnerships- and hence, to constitute a sort of power in Istanbul’s economy.65 Nonetheless, the integrated structure of the trade area created new poles in both its physical appearance and in social life at large as the 19th century wore on, reversing many of the existing balances of power.

The Axis of the ‘Divan’: Power and Everyday Life

The “Divanyolu” (Imperial Council Road) is described in 18th-century sources as a road of remarkable width which extended from the palace to Edirne Gate. Cerasi refers to this route as the “Divan Axis” and notes that it is not a straight and entirely linear line. The road integrated a number of different axes, at ninety-degree angles, into one thoroughfare. The “Divan Axis” is Istanbul’s most prestigious route, starting from Bâb-ı Hümâyûn (Imperial Gate) and connecting Hagia Sophia, Beyazıt and Fatih Complexes on its way towards Edirne Gate; as such, the “Divan Axis” integrates the three aforementioned platforms within the city walls. (Fig. 10) Part of this route’s prestige is that the axis diverges into multiple routes around the Şehzade and Fatih Complexes. “The Divan Axis resembles a river course in which crowds of people flow”.66

Whether or not the Divan Axis perfectly overlaps the Mese of Constantinople is an almost two-hundred-year-old question. There are two main reasons why the axis emerged on similar routes in the Byzantine and Ottoman periods: Istanbul’s topographical make-up and the sustained importance of Edirnekapı. On the basis of 15th-century engravings67, a number of Byzantine monuments can be identified along this axis, including the columns of Hagia Sophia, the Pillars of Iustinianos, Constantinos and Theodosius, the Valence Aqueduct, the Church of the Holy Apostles and the Aya Yorgi Church in Edirnekapı. Beginning in the 12th century, the axis from the Theodosius Forum to the Church of the Holy Apostles and Edirne Gate gradually became less crowded. Nevertheless, the main squares of the city that had been established through the Byzantine Mese and the hills that were home to the monumental structures were also well suited for Ottoman monumental structures. Underlining that it is impossible to find sharp differences or striking similarities between the Mese and Divanyolu, Cerasi states that the Ottomans accentuated the axis not by tracking down traces on the ground, but rather by following silhouettes formed by the monumental structures. It is possible, for this reason, to speak of a multipartite axis rendered complete by “routes that interconnect with imperial sites”68 instead of a straight and uninterrupted ceremonial road. The axis was named on the basis of its use as a public space in which Ottoman courtiers and the bureaucratic class met with the public, and occasionally came into conflict with each other. Additionally, concrete and abstract symbols of power were displayed along this axis. However, in the emergence of Divanyolu, the intensity of everyday life for inhabitants of the city grew to inhabit as great a role as the rituals of those with power. The character of the axis was additionally determined by the positioning of shops, bazaars and entertainment areas over time, which tended to develop around madrasas, Janissary barracks, libraries, tombs, imperial mosques and mansions belonging to state officials.

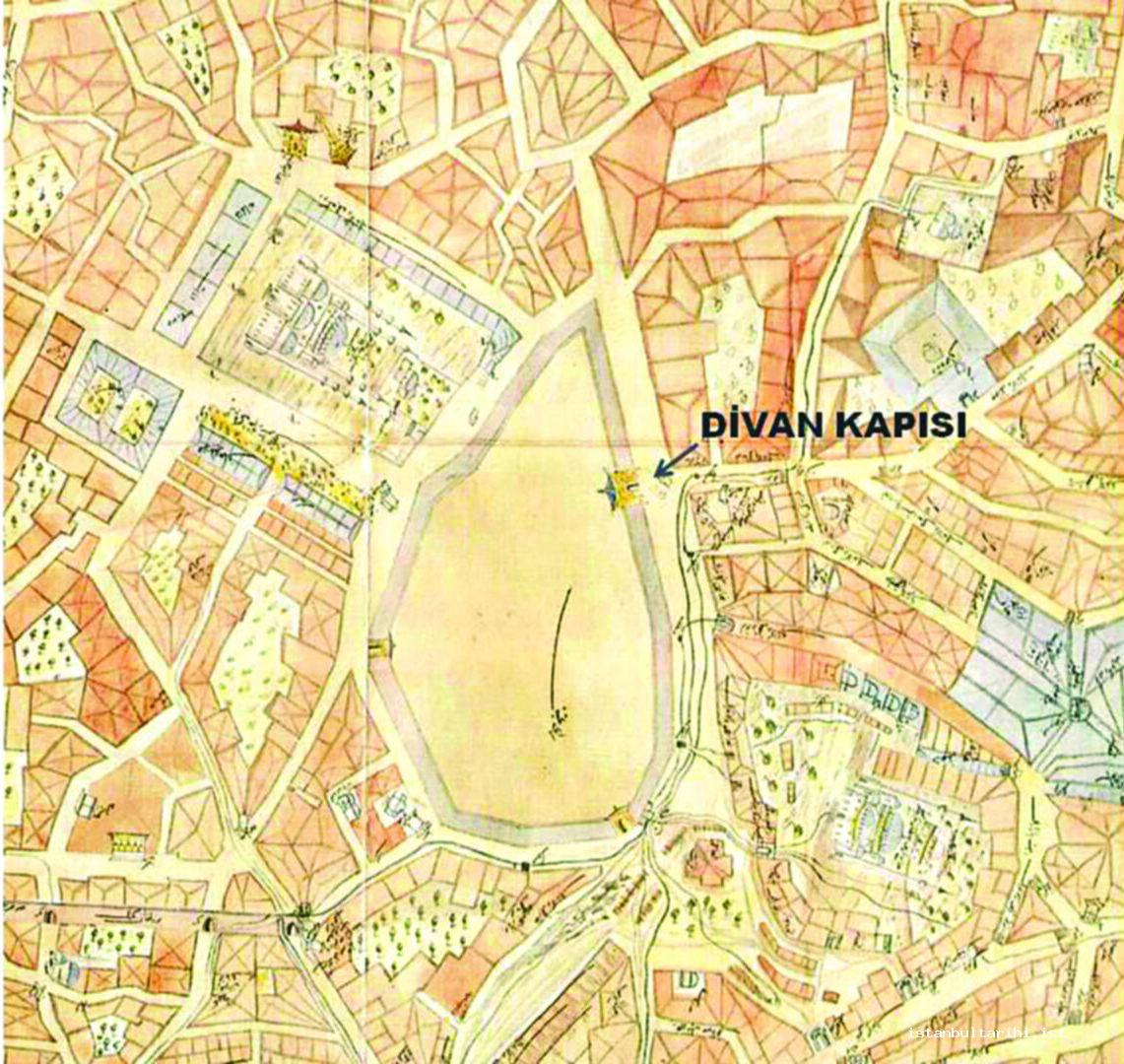

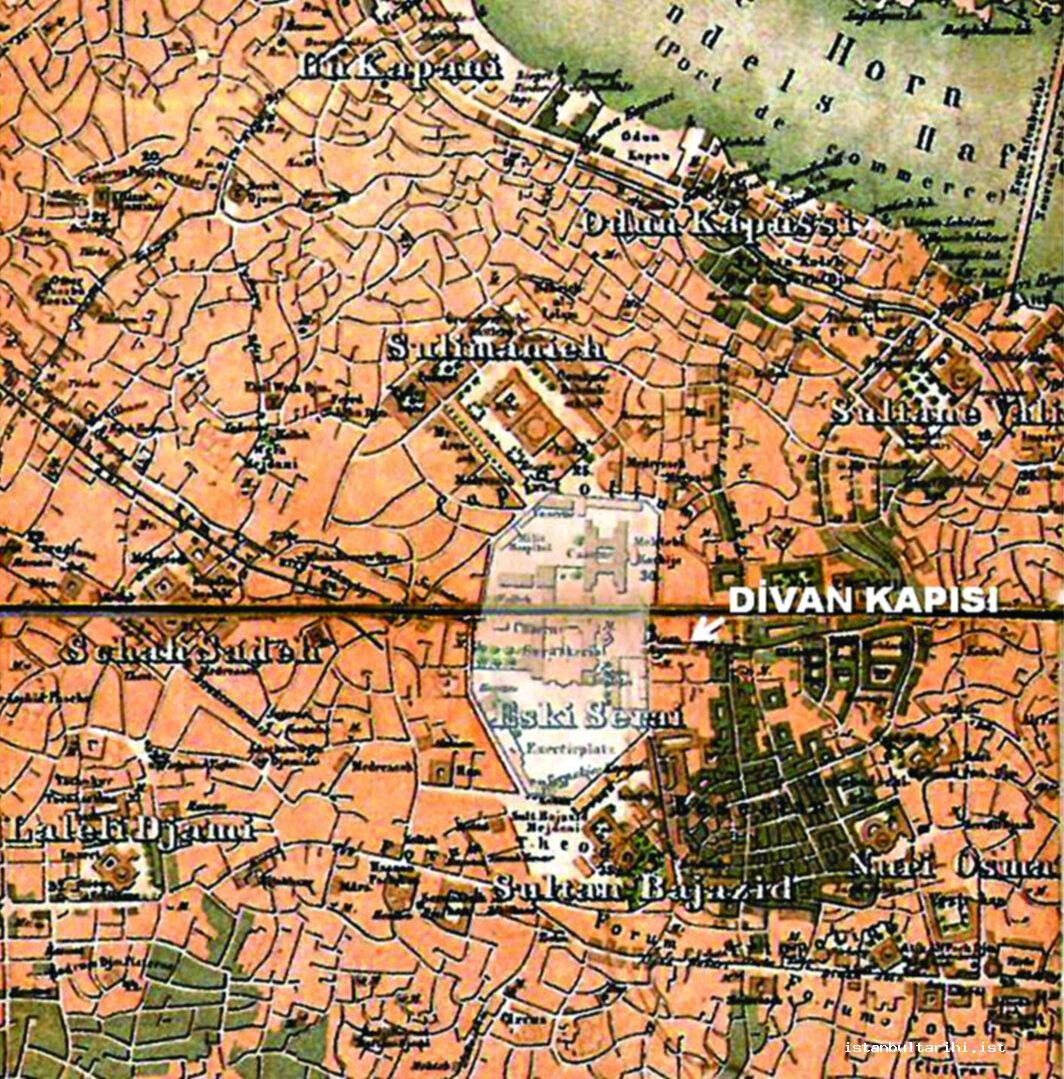

The construction of the first palace in what today houses the campus of Istanbul University constituted one of the major points of settlement on the Divan Axis. Following the construction of Topkapı Palace, the palace on the Divan Axis became known as the “Old Palace” (Saray-ı Atîk). The location of the Old Palace is notable in that it overlooked both the Golden Horn and Marmara Sea, was close to dynamic urban environments, and “occupied a sufficiently large piece of land.”69 It is also likely that the decision to build on this specific plot of land was based on the following as well: in cities such as Bursa and Ankara, a new market place would often be built in front of the main gate of the Byzantine fortress. In Istanbul, however, this appears to have occurred in reverse order, i.e., with the construction of a fort occurring next to an existing trade area. Because the quarter in the direction of the Golden Horn is referred to as Tahta’l-Kal’a (Tahtakale: Underneath the Fortress), we can understand that the walls of the Old Palace were perceived to be a fortress. The most important indicator we have of the connection between the “castle” and the trade area - contrary to what is known - is that the original main gate of the Old Palace was not that which opened into Beyazıt Square70, but that which opened eastward, that is, toward the main trade axis going down to the Golden Horn. The eastern gate of the Old Palace, drawn as a huge, magnificent gate in the Waterway Map of Bayezid II by Seyyid Hasan in 1813 (Fig. 11), was named “Divan Gate” (Council Gate) in the Istanbul City Plan drawn by Stolpe between 1855 and 1863. (Fig. 12)

In the first ten-year phase following the conquest, Sultan Mehmed II and his confidants examined Istanbul’s topography thoroughly. They had concluded, on the basis of military and political achievements in the Aegean, the Black Sea and the Balkan regions that the Ottoman state would soon become an empire, and they surely conceived of the recently conquered city before them as its capital. One of the first challenges they faced was in addressing the city’s lack of suitable housing. Mehmed II did not have the ready access to sufficient supplies of labor, building materials and organizational infrastructures that Süleyman the Magnificent would have half a century later, which makes his achievements all the more significant. In spite of these challenges, construction activity in the city entered a new phase in1463 following two important developments: the establishment of a new palace on the site of the ancient acropolis and the construction of a major complex for the sultan. Due to the size of these projects, but also owing to their locations, their development would come to determine the formation of urban space in Istanbul for generations to come. While the location for Topkapı Palace was selected to offer the sultan safety and seclusion, the site of the complex was chosen to give residents easy access to the opportunities and facilities of the empire.

The complex was to be built in the name of Mehmed II and on a plot of land which formerly housed the Byzantine Church of the Holy Apostles. The church, which had been granted to the Orthodox Patriarchate following the conquest, was abandoned by the patriarch in 1456 on the grounds that it was secluded and neglected; the church and its surrounding buildings were demolished in 1462. The site of the church, and later the Fatih Complex, was on the highest hill inside the city walls, overlooking the Golden Horn. Officials chose to build the church here in part because it would be the first structure seen by those entering the city through Edirne Gate. Focal points in multi-focal urban growth models tended to be located at certain distances from one another, and complexes built in the name of sultans were typically built on hills overlooking the city, or on specifically chosen routes. These tendencies explain in part why Mehmed II did not build his complex “in front of Hagia Sophia”.71 In selecting their construction site, they must have also considered the size of the complex, its functions, and the effect it would have on nearby quarters.

Apart from his expectation for the new complex to advance Ottoman architecture, Mehmed II also aimed to provide the capital with an educational institution that would train bureaucrats and scholars. Inside the Fatih Complex were a total of sixteen madrasas, eight of them for higher education (sahn), and eight for preparatory programs (tatimma); there was also a school and a library. Madrasas were groundbreaking institutions in the history of Ottoman education not only because of their number and capacity, but also due to their academic structure. “In the waqf charter of the Fatih Madrasas, it was stipulated that professors (mudarris) appointed to the madrasas for the first time had to be chosen from amongst those competent in the religious (transmitted) (naqlī) as well as intellectual sciences (aqlī), such as logic, philosophy, mathematics, and astronomy.” According to İhsanoğlu, Ali Kuşçu, the renowned mathematician and astronomer from Samarkand, may have influenced this decision. In addition, regulations in the Organizational Code of the Fatih Madrasa adjudged that professors in the Fatih Sahn Madrasas were required to be of the highest caliber in all of the Ottoman lands.72 These initiatives were the first steps on the capital’s way to becoming a center of scholarship.

Established on a piece of land approximately eleven hectares in size, the complex was constructed in the years between 1463 and 1471; it contained service units such as a printing house, a soup kitchen, caravansary and a hospital (in which a total of 383 people would be employed).73 Close to the complex were a marketplace called the “Sultan’s Bazaar”, the public baths of Saraçhane, Karaman, and Çukur74 - which would generate income for the waqf established for the complex - as well as houses for scholars.75 The complex’s layout also represented a first in Ottoman architecture. The mosque was placed at the center of all of the structures, which were built in a symmetrical, gridiron pattern. Units with independent courtyards were built around a main courtyard in the middle; in this symmetrical and hierarchical arrangement the central authority of the state is radically reflected onto the urban space. The vast courtyard in the middle is square in shape, which was previously unseen in the urban fabric of the Ottomans or the Seljuks given its size and geometry. With the establishment of the complex’s courtyard over the Divan axis, there emerged a complex which was fully integrated into the urban flow. Although the source of inspiration behind the design is unknown, some estimate that the Italian architect Filarete may have provided some inspiration, especially since he was in Istanbul around that time.76 Renaissance art may have also had an influence, particularly in consideration of Mehmed II’s interest in Italian art. One must consider, however, the likely impact which Asian geometrical arrangements had on the design of the complex, especially those originating from Samarkand and Isfahan.

Unlike his father, Bayezid II took a very cautious, conservative and pragmatic path towards construction activities in the city; this attitude is manifested in the Beyazıt Complex. The complex was centrally located at the intersection of the Uzunçarşı and Divan Roads, on the old site of the Theodosios Forum. The location provided those involved with the construction of the complex with a sufficiently large piece of land. However, the dimensions of the plot prohibited the complex to be built in line with the symmetrical design envisioned by Mehmed II. Instead, the buildings were constructed in an extended formation, similar to complexes found in Bursa. In this formation, an empty space was left between the southern gate of the palace and the mosque. In fact, Evliya Çelebi makes mention of this space in his writings, referring to it as “Beyazıt Square”. Part of the complex was a public bath which had been constructed using material left over from the Theodosius Column, which collapsed in a great storm in 1517 after the death of Sultan Bayezid II.77

The central cores of the Divan Axis had been formed in the 15th century. The axis was completed in a period in which the urban pattern, constituting the second phase of urban growth in Ottoman Istanbul, was complemented through comprehensive projects (1520-1617). The symbolic layers of the space were formed in part by palace rituals, which became a tradition during the reign of Süleyman the Magnificent. In this period, the sultan and his family members alone built six large complexes. Naturally, in order for construction activities of such caliber to be realized, the right economic and production conditions were needed. The housing problems encountered in the 15th century had been overcome, and the city’s population had reached an adequate size to allow for the amount of specialization needed in a capital city. A growing population with increasingly diversified demands resulted. To supplement the heirs of master tradesman who had been brought to the capital for major construction activities through the 15th century, accomplished merchants, architects, stone masons, muralists, tile craftsmen, carpenters, gunsmiths, and textile masters were brought to the city from Iran and Egypt following Selim I’s military campaigns in these countries; bringing in foreign artisans and tradesmen represented an innovation for Istanbul. In the construction of a complex commissioned by Sultan Selim I’s son on a hill overlooking the Golden Horn in Fener (1520-22), Egyptian and Iranian building masters and workers were employed. The project’s architect was Alaeddin Ali, an Iranian from Tabriz, who was also the first person to have conferred upon him the title of “Chief Architect of the Palace” (mimarbaşı).78

The Şehzade Complex, the first comprehensive work of Mimar Sinan, complemented the Divan Axis. Süleyman the Magnificent had actually contemplated commissioning this complex in his own name. As early as the first half of the 16th century, it had been a challenge to find space big enough for the sultan’s complexes. In the first stage of the construction of the Şehzade Complex land was provided in part by moving a section of the Janissary Corps to the valley of the Bayrampaşa (Likos) River. The passing of Heir Apparent Mehmed (1543) during construction brought about a change of mind, and the complex was dedicated to him. However, the mosque could not be completed according to the symmetrical arrangement as originally planned, which had suggested the mosque be placed in the structure’s central axis. A few years later, Süleyman the Magnificent decided to build a more glorious complex in his own name.

The construction of the Süleymaniye Complex made great strides in Ottoman architecture not only by virtue of its structure, spatial plan, and adornments, but also owing to the structure’s ultimate integration into the urban fabric, topography and the city’s silhouette. Celâlzâde Mustafa, a historian of the time, describes the selection of the land for the construction as follows: “He chose a piece of land of the Old Palace because it was both breezy and a high location overlooking the sea. It had been decided that such an auspicious complex had to be built on the best spot of the city, as pleasant as the mosque in Jerusalem, and that it had to cause an expansion of the heart.”79 The complex was to be built back from the Divanyolu Axis, but it would be prominent in Istanbul’s skyline from vantage points in Galata. The requisite space was obtained by parceling out the northern section of the Old Palace, while land belonging to the two waqfs was also needed towards the northwest of the new building site. To get these plots, private property was exchanged with land from the endowment (a process called istibdāl) on the order of the sultan. Süleyman the Magnificent soon grew impatient over the amount of time it was taking to finish the project and decided against using his initial plans, which called for the building to face a north-south axis in strict symmetry with three modules and a courtyard placed to the west of the mosque. We see here that the sultan may have occasionally had a hard time imposing his will on his subjects over the choice of building sites. Additionally, we see that a work donated as a waqf had to be built after obtaining the consent of everybody involved. The obligation for everybody, even sultans, to comply with the regulations of a waqf could be decisive in the structure of the organization.80 And with other examples taken into account, it is obvious that it had become difficult to come up with an empty plot of land in Istanbul, or to resolve land disputes regarding property ownership. In the process of constructing settlements, therefore, ownership was an important determinant. The Ottomans were at this time supplying land by altering decisions made by their ancestors two generations earlier instead of looking for plots on lands with Byzantine remains and ruins.

It is interesting to note that the number of structures belonging to women of the palace on the examined axis is limited. A double bath (1556) commissioned by Süleyman the Magnificent for his wife displayed the power of Hürrem Sultan in the palace: it was located in the most prestigious part of the Divan Axis, between Hagia Sophia Mosque and Atmeydanı.81 On the other hand, the selection of baths as a means of charity can be explained by the fact that it was the only public place open for women. Although it was outside of the axis, the location for the Haseki Hürrem Complex (1539), a remarkable structure in itself, was chosen on the Aksaray-Yedikule axis near Avratpazarı.82 It is clear that Hürrem Sultan, who initiated the tradition of dynastic women building complexes,83 wanted to leave a particular impact with her multifunctional complex. She was able to obtain its land, a narrow space, in an area which had already been largely developed. While the mosque was small in size, the hospital, the soup kitchen, and the madrasa were of greater magnitude.84 Nearly twenty years after her mother’s accomplishment, Mihrimah Sultan left behind a charitable legacy with the construction (1556-1560) of a complex on the former site of a church, close to the end of the Divan Axis near Edirne Gate.85 The era of the great sultan complexes came to an end with the construction of the Sultanahmet Complex (1607-1617), which brought to completion, as well, the city’s famous silhouette.

Throughout Ottoman history, the ruling elites and members of the dynasty assumed responsibilities in fulfilling the city’s social and cultural services. Naturally, their implementation and uses of city space varied depending on economic conditions, urban needs and the particularities of nearby terrain. We should also consider that the ruling segments of society would often try to accrue political capital as they spent resources on their pious endowments. Mahmud Pasha, Has Murad Pasha, Davud Pasha, Rum Mehmed Pasha, who were the viziers of Mehmed II, turned certain quarters of the city into focal points through the spending of their own spoils of war from various conquests. They did so by commissioning complexes which, while not as large as those of the sultans, were almost as functional in terms of the services provided. A complex built in 1497 in Çemberlitaş’s Constantinos Forum by Atik Ali Paşa, the grand vizier of Sultan Bayezid II, contains a mosque, madrasa, soup kitchen, tekke, and fountain. Following the pasha’s death, an Inn of Ambassadors was built in place of his palace opposite the mosque, to be used as a residence for foreign ambassadors; this location was a part of his pious endowment.86 In the second half of the 16th century, pashas gradually abandoned the practice of commissioning multifunctional complexes with a mosque. The last comprehensive pasha complex belongs to Cerrah Mehmed Pasha (1593). In the last quarter of the same century, a new custom gained popularity among the ruling elites. They now constructed complexes consisting of a madrasa and a tomb. The first example of this was built in 1569 in Eyüpsultan by Sokullu Mehmed Pasha and complexes of this sort were constructed until the end of the Tulip Era. The chief elements of complexes endowed by pashas were a madrasa and a tomb, and occasionally they were complemented by a fountain, tekke, school or a library. That such complexes - we may call them madrasa-oriented “smaller-scale complexes”- grew popular enough to determine the characteristic of the Fatih Complex-Çemberlitaş axis testifies to the growing permanence of the power displays in Divanyolu among a wider urban context. It is, of course, not a coincidence that this kind of organization took place in a period when viziers were truly powerful members of the state administration. Increases in the number of young students coming to Istanbul from Anatolia in the 17th century brought about an increased demand for madrasas. Examples of madrasa-oriented small complexes from the late 16th century are the complexes of Gazanfar Agha, Koca Sinan Pasha, and Kızlarağası; from the 17th century we may identify the complexes of Kuyucu Murat Pasha, Köprülü Mehmet Pasha, Kara Mustafa Pasha and Amcazade Hüseyin Pasha. A final example from this period is the Damat İbrahim Pasha Complex (1720), built next to the Şehzade Mosque in the Tulip Era. From the 18th century onward, those who wanted to leave behind pious endowments increasingly settled for single buildings such as fountains and libraries. The reason for the dwindling scope of donations –that is, from mosque complexes to fountain houses and simple fountains - was twofold: not only was it difficult to find a suitable plot for complexes in densely-populated sections of the city, particularly around the Divan Axis, but the amount of money statesmen were able to allocate for charitable works had fallen in parallel to the economic situation at large.87

The Divan Axis was the route of official ceremonies from the 15th to the late 18th century even though each ceremony used a slightly different route. Some of the major ceremonial processions included military parades held at times of campaigns, sword-girding processions that set out from the palace to Eyüpsultan (or vice versa, for the sword-girding ceremonies of heirs apparent) and Friday processions in which the sultan headed to the mosque of his choice for the Friday prayer; for the latter, the departure point was also the palace. The first recorded Friday procession of this sort dates back to the reign of Mehmed II.88 Processions which made their way from Topkapi Palace to the Fatih Mosque surely determined the character of the Divan Axis over the years.

In his research on Rome, Favro points out that triumphal processions were an integral part of the imperial capital “as a cosmological and political requirement,” and that routes of victory, determined by the flow of crowds, constituted the main routes of the city as well. The atmosphere of victory festivities attracts the most magnificent structures of the city on and around such routes. The owners of these magnificent structures were victorious commanders and other elites who wanted to keep their power over the masses visible at all times.89 Urban structuring of this sort, which took place in Rome eclectically over the centuries, grew to such levels that any first-time visitor to the city could easily discern the route taken by triumphal processions without any prior knowledge. As for Istanbul, Cerasi remarks, “Contents representing power and glory were composed of entourages and processions, yet unlike Rome in later ages, they were not glorified by being transformed into a holistic architectural image.”90 For the lasting effects of the grandeur of the event, they were probably relying on memory; it was in this way that the abstract layers of the space originated. On the other hand, a route consisting of parts with different functions and levels of intensity, and of a different social character, was not expected to integrate with ceremonial processions. When we look at historical records, the Divan Axis clearly stands out, particularly among areas that were heavily damaged in the great earthquakes of 1509, 1719, and 1754.91 Additionally, the frequency and spread of fires increased with the city’s rising population and building density. The area on the Divan Axis that took the brunt of many fires was the surroundings of the Fatih Complex, namely the quarters of Zeyrek, Saraçhane, and Atpazarı; Şehzadebaşı and the surroundings of the Janissary Barracks; the Beyazıt Complex and the surroundings of the Grand Bazaar.92 As this section of the Divan Axis was constantly managing demolitions and repairs throughout the 17th and the 18th centuries, the imagination of coherent and majestic architectural projects must surely have been limited.

Representations of power over the Divan Axis still managed to attract the building of new architectural structures; the social environment influenced by these structures in turn gave rise to new layers of representation. As an example, we may point to the segment of the Divan Axis between the Fatih Complex and Çemberlitaş, which was shaped by buildings that had been established as waqfs by grand viziers. Street silhouettes were established with incremental construction and sophisticated architectural solutions in the 17th and 18th centuries.93 However, what determines the character of this axis is more that the motivation for representing power in this space exceeded worldly bounds. The transformation of Divanyolu into an axis where tombs were agglomerated appears to have been caused by conflict between balances of power. These tombs were constructed in the name of viziers who knew that they could lose all their possessions instantly. As a result Divanyolu was a space in which secular and spiritual become a single whole, and in which symbols are linked to a historical era, an event or a figure woven into an inextricable whole.

A close study of the Seyyid Hasan map, dated 1813,94 reveals the actors and activities that shaped the Divan Axis apart from the ruling class. (Fig. 13) Some sections of the Divan Axis were more like sub-centers that contained specialized areas of production and trade. In a process beginning in the 1460s, four factors determined trade and production over this axis: land customs, the horse market, the surroundings of the madrasa, and the Janissary Corps.

By the end of the 17th century, during which the urban pattern had become increasingly more intricate, the Divan Axis and its immediate vicinity became an area with a concentrated population of students and scholars, owing to nearby madrasas built in varying sizes, programs, and levels of comfort. Professors took up residence particularly around the Fatih Complex and the Sultan Selim Complex.95 It is estimated that many of those who migrated to Istanbul from the late 16th century onward were unmarried men, and of those, the majority were students. It is known that two or three students would start to populate rooms previously used by only one student, and that newcomers had to stay in inns until finding a vacancy in madrasa dormitories.96 This explains why there were so many inns around Şehzadebaşı, as shown in Seyyid Hasan’s map. The growing number of students was the chief reason for the commercial specialization in book-dealing and stationery items around the Beyazıt Mosque. In the 1810s, shops that made and sold ink, reed pens, inkwells and paper had grown in remarkable numbers over the trade axis that extended from the Beyazıt Complex to the Şehzade Complex, including the Bazaar of Book Dealers (Sahhaflar Çarşısı) which had formed as part of the Grand Bazaar. Pharmacists and herbalists (ispençiyar) were also located nearby, seemingly accessible from each of the Süleymaniye, Fatih, and Haseki Hospitals.97

A small sub-center formed in Karagümrük because goods that came from the Balkans entered the city through nearby Edirnekapı and were supervised at this point. The Fatih Complex had a caravansary, bazaars and commercial buildings in its immediate vicinity because the land axis of trade that came from Central Europe ended at this point. The revival of the Amsterdam-oriented land trade on the Central Europe-Balkans line in the 17th century had major impacts on the Ottoman state as well.98 That these developments brought about vitality in production and the market environment around Edirne Gate, Karagümrük and Atpazarı is an assumption that has not yet been verified. Another factor that made the district surrounding the Fatih Complex attractive is the Atpazarı quarter, which was established east of the complex just after the city’s conquest. Given the amount and diversity of demands in the capital in the following centuries, we can assume that Atpazarı had a lively commercial atmosphere. It must also be considered that the number of horses employed in freight transport and the production sector was significant.99 A sector with an advanced level of specialization developed around horse husbandry, ranging from keeping horses to equipping them.100 When a saddler was established opposite to Atpazarı in order to generate income for the Fatih Complex the potential for growth in this sector surely must have been considered. Mortan and Küçükerman claim that a total of 146 artisans worked in 110 shops in the saddlers’ bazaar and that some of them were also Janissaries.101