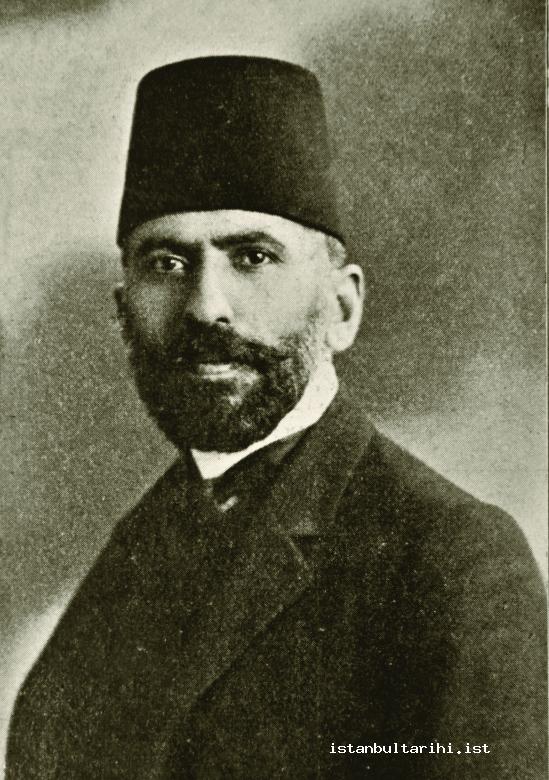

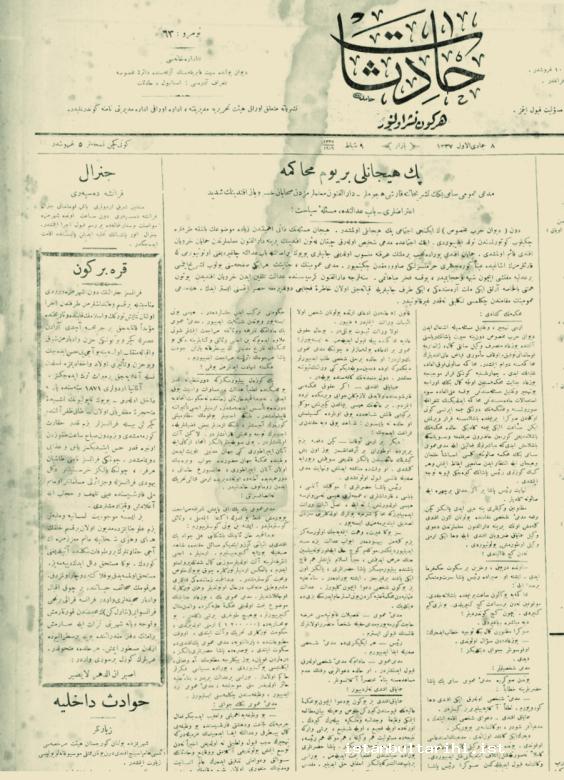

French general Franchet d’Esperey—who entered Istanbul with his forces on February 8, 1919—organized a victory parade from Istanbul towards Beyoğlu. During the parade, he managed to offend people by snapping his whip and silencing the Ottoman band—which was only there to welcome him—because it had startled his mount. He ordered Süleyman Nazif’s arrest and, according to some reports, execution for criticizing this incident in his newspaper.1 When Süleyman Nazif heard of the order for his arrest, he personally went to an Istanbul police station and turned himself in; however, police captain Mehmed Ali Bey refused to surrender the author of Hâdisât to the French. Yusuf Franko Pasha, an Ottoman bureaucrat of French descent who was in Istanbul at the time, intervened and arranged a meeting between the French general and Süleyman Nazif. This meeting prevented an arrest2 but was not the end of the incident. French military officers hastily arrested lieutenant Aziz Hüdai Bey, a member of the censorship commission, for allowing the publication of an article titled “Kara Bir Gün” (“A Dark Day”). Lieutenant Aziz Hüdai Bey was only released from prison pending trial after fifteen days but he lost his job.3 The French general’s harsh reaction to Süleyman Nazif’s article increased its popularity and hundreds of thousands of handwritten copies were produced. It was widely distributed and hung around the city on fliers.4 As with many writers and speakers of the time, Süleyman Nazif was later exiled to Malta. He returned to Istanbul at the beginning of 1922 after spending twenty months in exile. He continued to write works that expressed his nationalistic feelings.5

A Dark Day

The French general’s arrival to the city opened a wound in the hearts and in the history of Turks and Muslims—a wound that continues to bleed today—and led to demonstrations by some of Istanbul’s citizens. Regardless of whether centuries pass and our sadness and misfortunes turn into enthusiasm and prosperity, we will feel the pain of this incident and pass this sorrow and grief on to our children and grandchildren. This is a legacy they will cry about for generations. Even when the German army entered Paris in 1871 and passed under the Arc de Triomphe de l’Étoile, a monument inscribed with verses about Napoleon’s victories, the French were not so insulted. They did not feel this incredible sorrow and pain because it was not just Christians, but also Jews, Algerian Muslims, and anyone who considered themselves French, who cried, were ashamed, and lamented during that moment of national mourning.

We sensed that the bitterest of insults was being slapped on our grief when some of our citizens—who owe their national and linguistic being to Istanbul’s great majesty—still only felt joy in response to the incident. We cannot say that our grief was undeserved. If it was undeserved, then we would not have been afflicted by such a calamity. There are pages of fortune and misfortune in every nation’s life. It appears that such a painful page has been written in our great nation’s book of destiny, a nation that saved King Francis I of France from the prisons of Charles V and repeatedly sieged the great city of Vienna. Circumstances change—sometimes unfortunately. There is a beautiful saying in Arabic: “Isbir, fa-inna al-dahra lā yasbir.” It means, “Be patient, for certainly time is not patient.

FOOTNOTES

1 Hicran Göze, “Mehmet Akif’in Büyük Dostu Süleyman Nazif”, Kubbealtı Akademi Mecmuası, 2008, no. 146.

2 Kemalettin Şükrü, Mütareke Acıları, Istanbul: Selamet Matbaası, 1930, pp. 40-48.

3 BOA, DH.KMS, 49-1/93; BEO, 4560/341981, 4567/342487.

4 Mümin Yıldıztaş, Yaralı Payitaht/İstanbul’un İşgali, Istanbul: Yeditepe, 2010, p. 5.

5 Ömer Derindere, Yenilgi Yenilgi Zafere, ed. İbrahim Öztürk, Istanbul: Aydınlık Yayınları, 2014, p. 16; Şükrü, p. 49.