Liberation of Istanbul

Upon the success of the National Struggle and expulsion of the Greek army from Anatolia, the Allied Powers called a ceasefire and signed the Armistice of Mudania on 11 October 1922. Articles 11 and 12 of the Armistice called for occupation forces to remain in the Turkish straits and Istanbul until the end of peace treaty negotiations.

Despite the company of his attendants and gendarmerie guards section, Refet Pasha, representing Turkey during the hand-over of the Thracian territories pursuant to the Armistice of Mudania before the Allied Powers, left Mudania on the steamboat Gülnihal on the morning of 19 October and arrived at the coast near Istanbul in the afternoon. British warships stopped the Gülnihal and announced that Refet Pasha had permission to disembark in Istanbul but the gendarmerie guards section did not; the gendarmeries spent the night on the steamboat.

Refet Pasha’s disembarkation on the Kabataş Pier caused great excitement in Istanbul. As a result of his contacts, the gendarmerie guards section could only disembark the following day. In this way, a Turkish brigade arriving from outside entered Istanbul years later.

During the peace treaty negotiations that began on 20 November 1922 in Lausanne, evacuation of Istanbul was among the matters the Turkish delegation emphasized. Many disputes arose in the following days; negotiations came to a halt without any progress, and the Turkish delegation departed from Lausanne on 4 February 1923. Following the renewed invitation of the delegation by the Allied Powers to Lausanne under the leadership of İsmet Pasha, Turkey’s minister of foreign affairs, the second phase of the negotiations commenced on 23 April 1923, and the Turkish delegation gave the issue of Istanbul’s evacuation the highest priority. In response to the Turkish delegation’s demand that the occupation forces evacuate, the president of the British delegation, Sir Horace Rumbold, stated that this would not be possible without the ratification of the Allied Powers parliaments. However, İsmet Pasha persisted in this demand, and stated several days later that the evacuation should take place shortly after the signing of the peace treaty, that they would not wait for the ratification of the Allied Powers parliaments, that no peace treaty would be recognized by the Turkish government unless it included the evacuation.

The Turkish delegation regarded the evacuation as vital and continued to insist that it take place before the ratification of the treaty by the parliaments of the Allied Powers. However, the British Ministry of Foreign Affairs did not want to negotiate this issue early in the negotiations and instead preferred to reserve it as their trump card. Whenever İsmet Pasha raised the issue, Horace Rumbold sought to postpone its discussion. According to Rumbold, the Allied Powers would probably execute the evacuation if the negotiations ended in success. Strictly speaking, Istanbul and Çanakkale would be treated as surety throughout the negotiations. The British were able to postpone the Turkish request throughout May and June.

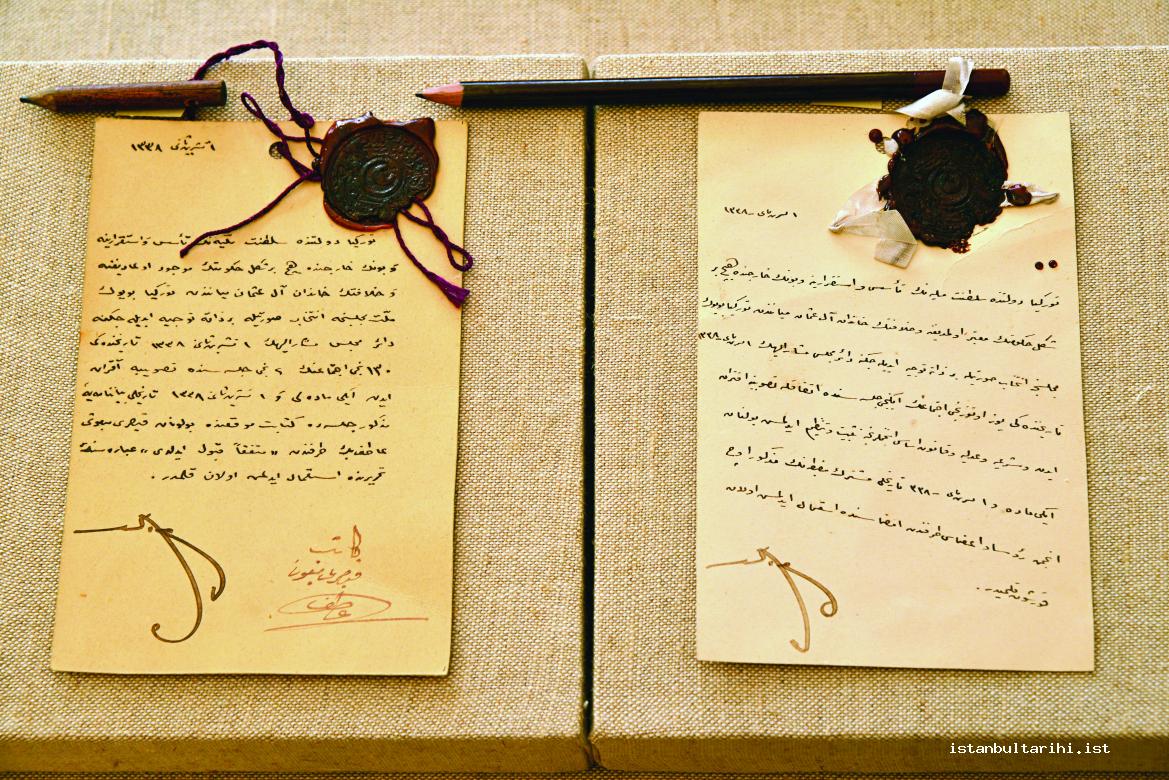

However, following a diplomatic note from İsmet Pasha, the Allied Power delegations noted that uncertainties around the evacuation issue had become untenable, and a protocol for the evacuation was finally drafted on 6 July 1923. According to the seven-article draft protocol, the evacuation would commence as soon as the high commissioners were notified of the ratification of the treaty by the Grand National Assembly of Turkey and would be completed within six weeks. As a result, all problems regarding the evacuation were eliminated before the official signature ceremony in Lausanne, and everything was ready for the process to start. The Declaration and Protocol Relating to the Evacuation of the Turkish Territory Occupied by the British, French and Italian Forces was signed on 24 July 1923 in Lausanne, confirming that the evacuation would be completed within six weeks. Discussion of the Treaty of Lausanne in the Grand National Assembly of Turkey began on 21 August 1923, and the treaty was ratified on 23 August. İsmet Pasha notified the High Commissioners in Istanbul of the ratification by means of a note. The evacuation period was officially begun at midnight on 23 August, with the Occupation Powers liable to complete it by 4 October. Preparations by the Allied Powers gained further momentum following the official commencement of the evacuation period.

On 30 August, a newspaper article noted that 8,000 British soldiers had departed Istanbul since the evacuation started. While the British took the evacuation seriously, the French moved more slowly because expected steamboats from Marseille had not arrived.1 The Italians began to evacuate their relatively small number of soldiers. Another development that occurred during the evacuation process was the abolition of the Allied Powers’ municipal police force in Istanbul by Selahaddin Adil Pasha following a meeting with General Harrington. The French began evacuating Bakırköy on 1 September, and the French forces in Hadımköy left within a week after that.

The British evacuated and handed over the Tabya Kışlası (Bastion Barracks) in Ortaköy, used as the Armenian orphanage, on 3 September 1923, and shortly thereafter began to evacuate additional barracks and residences. They also handed over a great number of weapons and equipment owned by the Turkish fleet. On the Anatolian side, barracks in Kadıköy were evacuated.2 French shipping gained speed during these days. Senegalese soldiers staying in the barracks in Sarayburnu and some weights set out on a French steamboat to Marseille on 4 September. The French forces also started evacuating the Demirkapı and Gülhane barracks. Since the British forces had started their evacuation before the ratification of the treaty, they successfully finished four thirds of their evacuation by 4 September.3 Private residences and buildings were evacuated on 5 September. The occupation forces waiting for the Turkish warships departed the Golden Horn. The battleship Yavuz in Tuzla was expected to be released in a week.4 The occupation of the Turkish seas was almost over. In addition, the following places were expected to be evacuated within days: the customs house in Sirkeci, the gendarmerie station in Ağa Hamamı, the police department on Mektep Street, and the radiophone/telegraph station in Okmeydanı. A report by Dr. Adnan Bey reiterated that British and French aircraft, weapons, ammunition, and equipment were loaded on the steamboats. All British aircraft were removed from Ayastefanos (Hagia Stephanos) and brought to the port for transfer.

In the second week of September, the British evacuated the Summer Palace of Maslak and Enver Pasha’s mansion. The French were still in the process of evacuating Çırağan Palace and the barracks of Rami. Other places evacuated by the French were the Military Tailor in Ahırkapı, private buildings near Hagia Sophia, Talat Pasha Mansion, and pavilions in Gülhane. The flag ceremony which was to take place in the last stage of evacuation and hand-over would start in conjunction with the hand-over of Mekteb-i Harbiye (the Military Academy), and Turkish flags would replace those of the Allied Powers.5 Around the same time, the French forces were expected to have evacuated the weapons and ammunition warehouses in Rami, Metris, and Davutpaşa.

The Allied Powers collectively declared that they would depart from Istanbul by 2 October 1923—earlier than originally planned—as they completed the evacuation two days earlier. Details of the evacuation ceremony were negotiated as follows: the Allied Powers’ flags would be replaced by the Turkish flag before the general of the Allied Powers and Selahaddin Adil Pasha in Mekteb-i Harbiye on the morning of 2 October, and following a ceremony at the Dolmabahçe dock at 11:00, the ships carrying the remaining Allied Powers soldiers would embark and leave Istanbul.6

As of 23 September, three British, one Italian, and two French battalions were still present as occupation forces in Istanbul.7 The Haydarpaşa–Gebze line was handed over by the British on 25 September.8 The news media reported that a Turkish battalion was expected to enter the Istanbul region within 24 hours after the completion of the evacuation. This battalion, which had fought bravely at every stage of the War of Independence and had saved Mudania and Bursa from occupation and captured many Greek battalions, was nicknamed the Iron Legion by the Greeks. It was expected to march from Pendik to Istanbul.9 The Port of Istanbul was handed over to Turkish committees on 28 September; the evacuation and hand-over were expected to be completed by the last day of September.

Occupation forces in Istanbul published an official notice announcing the end of occupation and the evacuation. According to this notice, occupation by the Allied Powers would end in the afternoon on Tuesday, 2 October. A ceremony was planned to take place at the Port of Dolmabahçe at 11:30 on that day, with British, French, Italian, and Turkish soldiers participating. To mark the end of the occupation, Turkish soldiers would salute Occupation forces and Turkish forces respectively. Following this ceremony, commanders of the Allied Powers would depart from the port on steamboats. The boats would pass through the navy of the Allied Powers at 15:00, and all other remaining ships would depart after that. Diplomats in Istanbul were also invited to this ceremony and allocated a private space from which to view it. In the meantime, the occupation forces were carrying out the last evacuation. The Tatbikat Mektebi (School of Military Drills) in Haydarpaşa was handed over to Turkish committees through a special ceremony. The evacuation would be completed with the hand-over of Tophane barracks, Mekteb-i Harbiye (Military Academy), the gendarmerie department in Beyazıt, the Municipality, and locations occupied by the Italians in Salıpazarı.10 During a farewell visit to Selahaddin Adil Pasha in his office on 29 September, commanders of the occupation forces stated that they were departing from Istanbul with good and unforgettable memories.11 The British also handed over Kağıthane and Maslak on 29 September. Most of the occupied buildings between the barracks and the palace were returned to their owners. The French were also expected to hand over several buildings near Hagia Sophia, the gendarmerie department in Beyazıt, Süleymaniye, and Rami barracks in addition to some other buildings. Both the British and French would have evacuated most occupied spots and places within two days. These were the last evacuation steps of the Allied Powers.12

Grand military barracks started to be handed over to Turkish committees on 30 September. During the British hand-over of the barracks of Maçka, weapons including 2,000 machine guns and 150,000 rifles were xxxx. The evacuation of the barracks of Orhaniye was completed, and arsenals, Sipahi Ocağı (the riding club at Maslak), the military hospital and arsenal in Tophane, and the Mekteb-i Harbiye were declared to be evacuated on 1 October. Following the hand-over of military buildings on the same day, a general protocol regarding the evacuation and hand-over of Istanbul was to be signed by Selahaddin Adil Pasha and commanders of the Allied Powers. To accommodate the ceremony at the Port of Dolmabahçe on 2 October, tram traffic in this district was discontinued from 11:00 to 15:00.13 At the end of September, the hand-over was complete except for the Mekteb-i Harbiye, a French-occupied transfer department in Sarayburnu, and Italian-occupied buildings in Salıpazarı; these were planned to be relinquished on 1 October. A flag ceremony was to be held in Mekteb-i Harbiye, which had been used as the headquarters of the Allied Powers, at 9:45 on 2 October, and the Italian- and French-occupied buildings were to be handed over in a ceremony at 10:00. Thus, there would not remain a single occupied building as of 10:00 on that day.

The long-planned ceremony did take place. The General Hand-Over and Acceptance Protocol was signed on 2 October by General Harrington and Selahaddin Adil Paşa on the Arabic, an ocean liner that was to take the general to Britain. Thus, it was entered into the written record that the hand-over of weapons, ammunition, and equipment controlled by the occupation powers was complete.14 Ceremony companies of the occupation forces and the Turkish military took their places at the Port of Dolmabahçe on 11:30 on that day. Proceeding to the square, General Harrington, General Mombelli, and General Charpy welcomed Selahaddin Adil Pasha and started the inspection of the troops together. The salute march was played throughout the inspection, and loud applause and background noise arose from the people present at the ceremony. After General Harrington’s hand-shake with the commander of the Turkish company, the flags of the Allied Powers were brought to the square, escorted by four soldiers, and the national anthems of these states were performed. Then, when soldiers carrying the Turkish flag proceeded to the middle of the square and stopped in front of Selahaddin Adil Pasha, the Turkish national anthem was performed. Afterward, allied platoons and generals passed by Selahaddin Adil Pasha with the French band at the forefront. The French platoon was followed by Italian, British, and Turkish platoons. After saluting Selahaddin Adil Pasha, the generals saluted the Turkish flag before the Turkish company.15 Thereafter, soldiers of the Allied Powers and their generals proceeded by motorboat to the ships on the Bosphorus. Watched by thousands of people from the shore, the Arabic set sail on the Marmara Sea at 15:10. Other steamboats followed, and finally the warships departed from Istanbul,16 and the evacuation was complete. Turkish soldiers were the only military presence remaining in Istanbul. After experiencing captivity from autumn 1918 to autumn 1923, Istanbul became a de facto liberated city on 2 October and officially free on 6 October, leaving sorrowful years and memories behind.

Proclamation of the Republic

It was necessary to eliminate uncertainties regarding the regime that emerged after the abolition of the sultanate on 1 November 1922, but this had to wait until the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne. It was achieved by amending the Teşkilat-ı Esasiye Kanunu (Constitution of 1921). The institution of the caliphate remained in existence after the abolition of the sultanate and became a center of attraction for the political opposition. This necessitated immediate action to define the regime in clear terms. During these disputes, the Republic was proclaimed on 29 October 1923.

Proclamation of the Republic had wide repercussions in Istanbul. The news officially reached Istanbul at midnight on 29 October. III Corps Commander Şükrü Naili Pasha published a notice in Istanbul. Some newspapers dated 30 October carried the headline “Republic Officially Proclaimed Yesterday.”17 On this occasion, 101 artillery shots were fired, first from the barracks of Selimiye and then at various points in the city. Initially worried by the shootings and taking to the streets, Istanbulians celebrated with enthusiasm upon hearing the news.18 People rushed to Sultanahmet Square early in the morning, and trams had to stop due to overcrowding on the streets. In the early morning on 30 September, Istanbul was covered with flags, and ceremonies commenced at 15:30 in the Governorship and Army Corps. Parties were organized in various districts in the evening. Foreign missions in Istanbul were notified by the Istanbul representative of the Ankara government, Dr. Adnan Bey, that the form of state was republican, and Mustafa Kemal Pasha was elected as the president. Upon the announcement of the proclamation of the republic in the city, stores and foreign businesses raised Turkish flags. On both sides of the Bosphorus, wharves and steamboats were decorated. Foreign ships in the port flew Turkish flags as well. Torchlight processions were organized in the city, the people gathered and cheered “Long live the Republic!” and mosque minarets and state offices were illuminated.19 Celebrations in Istanbul continued on 31 September. The whole city was decorated. Parties were organized in Sultanahmet, Beyoğlu, and other districts.20 A newspaper of the same date reported that students, the Labor Union, and association members gathered in Sultanahmet Square early in the morning; scouts marched in their uniforms.21 Caliph Abdülmecid Efendi congratulated Mustafa Kemal Pasha with a telegraph on 31 October 1923. Replying to the caliph by telegraph a day later, Mustafa Kemal Pasha expressed his thanks.

Press reactions to the proclamation of the republic can be divided into two categories. In an article dated 31 October 1923, the İkdâm newspaper highlighted that the Republic was not recently proclaimed, and that the name of the form of state established in conjunction with the abolition of the sultanate had been proclaimed, and congratulated Mustafa Kemal Pasha and wished him success.22

Tanîn and Tevhid-i Efkâr newspapers did not share the same opinion regarding the Republic. Tanîn mentioned an interview given by Ali Fuat Pasha to another newspaper in which he stated that the Republic had been proclaimed in the absence of two-thirds of the parliament. Tanîn added that the Republic could yield beneficial results in the event of due execution.23 The strongest critique came from Tevhid-i Efkâr, which stated that the Republic was materialized fait accompli and things could not be fixed this way. Emphasizing that he would like the Republic to be successful, Ebuzziyade also reiterated his doubts regarding the matter. Deemed to be responsible for the proclamation of the Republic, Celal Nuri and Ahmet Ağaoğlu were heavily criticized by Tevhid-i Efkâr for not endowing the public with an idea of their future deeds.24 In the following days, Tevhid-i Efkâr continued its criticisms.

There was, however, no public opposition. Rather, opposition and debate were primarily limited to the press. Most Istanbulians welcomed and celebrated the proclamation of the Republic. In the following weeks, the Istanbul press concluded that it was unnecessary and useless to dwell on the matter, and the disputes came to an end.

Reactions to the Abolition of the Sultanate and Caliphate in Istanbul

When Refet Pasha, delegated to receive Thrace pursuant to the Armistice of Mudania, arrived in Istanbul, Ali Nuri Bey, staff major and aide de camp of Sultan Vahdettin, welcomed him on behalf of the sultan. Refet Pasha saluted Vahdettin as the reverend caliph and asked that his most sincere religious feelings be conveyed to him. His omission of the title of sultan in the formal welcome ceremony was a clue to the future of the sultanate. In his telegraph to Mustafa Kemal Pasha sent on 17 October, Grand Vizier Tevfik Pasha asserted that governments of Ankara and Istanbul would both be invited to the peace conference and offered to act in unison. In his reply on 18 October, Mustafa Kemal Pasha stated that the state of Turkey would be represented at the conference only by the Grand National Assembly of Turkey. Invitations to both governments to the conference in Lausanne by the Allied Powers, and the continuous insistence of Grand Vizier Tevfik Pasha, created a problem regarding representation. During discussions in parliament on 30 October 1922, both supporters and opponents of Mustafa Kemal criticized the sultanate.

On 1 November 1922, the sultanate was abolished following a motion submitted by Dr. Rıza Nur and 78 deputies. The motion included the following statement: “The title of caliph belongs to the Ottoman dynasty and the Grand National Assembly of Turkey shall elect from among the dynasty the most mature and competent member in terms of learning and morality as the caliph. The state of Turkey shall be the fulcrum for the office of caliphate.” While members of the Tevfik Pasha government submitted their resignations on 4 November 1922, the government of Ankara instructed Refet Pasha to take over the administration of Istanbul. During talks with Horace Rumbold, the British high commissioner, in Istanbul on 7 November 1922, Vahdeddin asserted that the government of Ankara was illegal. However, Rumbold advised him that the issue of legalization of the government be adjourned and that Vahdeddin should face that reality, as Ankara would be participating in the conference with a representative. Vahdeddin also asked whether they would help him in case he desired to leave Istanbul. Another notable development was the use of the caliph title without reference to Vahdeddin in a khutbah on 10 November 1922. Vahdeddin, the last sultan, left Istanbul on the British battleship Malaya on 17 November 1922. Indubitably, this development was long desired by the government in Ankara. Newspapers reported that they had been informed about these developments by the British agency’s commentary. It was stated in the commentary that Vahdeddin’s application was accepted as a result of his two-year-long initiative and he was being transferred to Malta on a battleship.25 While Vahdeddin was leaving Istanbul without waiving from the title of caliph, Refet Pasha notified Rauf Bey, the president of the Council Cabinet in Ankara, of this development. Consulting with the sultan’s son, Abdülmecid Efendi, that evening, Refet Pasha conveyed to Rauf Bey by wire that decisions taken in Ankara were approved by Abdülmecid Efendi. On 18 November, Abdülmecid was chosen as caliph. The Law Relating to the Abolition of the Caliphate and Displacement of the Ottoman Dynasty Outside the Republic of Turkey was enacted on 3 March 1924. Action was taken without delay following the adoption of the law. After the Ministry of Interior notified the governor of Istanbul regarding this development, civilian authorities formed a committee under the presidency of the Istanbul governor, Haydar Bey. All telephone lines were disconnected on the night of 3 March at 22:30, and Dolmabahçe Palace was surrounded by military and police troops. Abdülmecid Efendi, who was in the palace library, was notified of the law by Haydar Bey, the Istanbul governor, and Sadettin Bey, chief of police, at midnight. Caliph Abdülmecid Efendi’s protest and the desire to contact Ankara did not yield any results, and Governor Haydar Bey warned the caliph that he would be forced out if necessary. News reports indicated that it was probable that Abdülmecid would leave for Egypt. The newspapers also wrote that Dolmabahçe Palace had been brought under control by the police and the caliph was ready to leave.26

Caliph Abdülmecid Efendi came by automobile in the company of his two wives, son, daughter, secretaries, and personal doctor, escorted by police officers. Before leaving Dolmabahçe, he prayed for his nation’s safety with his hands open. Two separate groups moved from Dolmabahçe, and one drove to Sirkeci. Considering the danger of embarking from Sirkeci, the caliph was taken to Çatalca and embarked on the Simplon Express at midnight. He was given travel allowances and passports. The passports bore only exit stamps from Turkey and entry visas issued by the consulate of Switzerland. Thus, the newspapers’ predictions missed the mark, and it was understood that the destination was Switzerland instead of Egypt. Remaining members of the dynasty would go abroad within a short period of time. These included 16 grooms and 100 princess’s sons (sultanzade). The number of those going abroad totaled 141. A 6 March newspaper story headlined “Abdülmecid Efendi Went Abroad Yesterday Morning” reported that Abdülmecid Efendi granted a final interview before leaving and stated that he would not be exploited by the policies of the foreigners. A story titled “Dynasty Members Leaving Today” reported that most members of the sultan’s family were expected to go to Hungary, Austria, France, or Italy, and some to go to Egypt or Switzerland.27 Another newspaper article reported that the sultan’s son, sultans, and grooms received their passports from the Police Directorate. Other information was more tragic. Since dynasty members had probably become aware of the results of the parliamentary negotiations a few days earlier, they tried to sell their belongings, and people took advantage of this opportunity to purchase these belongings at prices below their worth.28 The press asserted that all male dynasty members had departed by 6 March 1924. A total of 60 people departed on the steamboat Milano; at that time not many dynasty members remained in the city. A newspaper dated 7 March used the headline “Tonight All Dynasty Members Gone.”29 Another newspaper wrote on 8 March that a group had departed from the Sirkeci train station the night before at 21:00.30

Due to the special conditions of the period, these developments were reported without commentary in the Istanbul press, and there was no public reaction.

Another matter of concern during this period was the question of names to be included in the khutbahs of the first Friday prayer following the departure of the caliph. The office of the Mufti in Istanbul stated, in a written notice to the mosques, that prayers should be chanted only for the security and happiness of the nation and glorification of Islam and that no names should be mentioned. The police department warned the mosque preachers, in a notice they were required to sign, that anyone mentioning names would be subject to legal proceedings. As it was an unforeseen situation, the public and press curiously awaited the khutbah on 7 March 1924, but preachers did not mention anyone by name. In the following days, issues related to the state of the caliphate and dynasty members gradually dropped off the agenda. A new period had now started for the Ottoman dynasty abroad.

First Arrival of Atatürk in Istanbul During the Republican Era

After the success of the National Struggle, Mustafa Kemal Pasha paid his first visit to Bursa. A visit to western Anatolia took place in early 1923. Mustafa Kemal Pasha responded positively to an invitation to visit Istanbul on the occasion of the city’s independence in autumn 1923. Although he did not visit Istanbul in 1924, Mustafa Kemal Pasha passed through the city in transit. Embarking on the battleship Hamidiye on the morning of 12 September 1924, he proceeded to Trabzon via Istanbul. Despite invitations from Istanbul in the following years, no visit took place for a long time. Ultimately Atatürk put an end to the long wait by visiting in 1927. Travelling to Ankara in mid-June 1927, Istanbul Mayor Muhiddin Bey invited Mustafa Kemal to Istanbul, and his invitation was accepted this time.

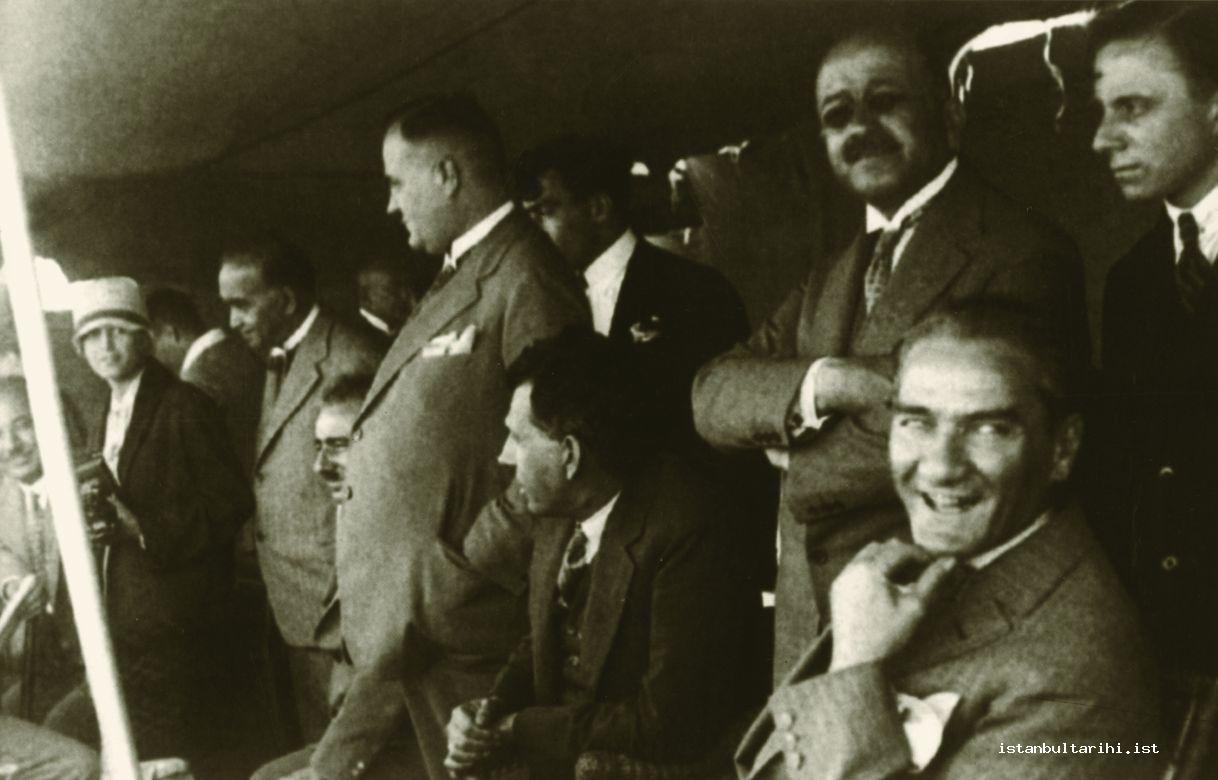

The departure of Mustafa Kemal Pasha from Ankara to İzmit by train on 30 June 1927 culminated in the highest level of mobility in Istanbul. Triumphal arches were set up, and signs praising Gazi Mustafa Kemal were hung in every street in Istanbul. The press wrote that a welcoming committee of 800 people would be waiting for the yacht Ertuğrul at Büyükada. The municipality of Istanbul asked for cigarettes named 1 July Souvenir from the Stage Management to be produced as mementos.31 When the day finally arrived, 13 small and eight large steamboats owned by Seyr-i Sefain İdaresi (the Ottoman Navigation Administration), 12 steamboats belonging to the Şirket-i Hayriye (Auspicious Company), and seven steamboats of the Golden Horn Company set sail from the dock of Galata to the Marmara Sea; the steamboat Burgaz departed at 11:00 as planned. Following the news that the Ertuğrul, which was carrying Gazi Mustafa Kemal, departed from İzmit at 12:50, all steamboats blew their horns at 15:15. As the Ertuğrul appeared in the distance, the Burgaz and the motorboat Istanbul, carrying the welcome committee, proceeded. A naval fleet was standing by offshore as well. The Istanbul approached the Ertuğrul, and the committee extended their welcome on behalf of the residents of Istanbul. Cannons were fired while the Ertuğrul passed by Selimiye. Thousands of Istanbulians gathered in Üsküdar and Sarayburnu to witness this historic day. Following the Anatolian coast, the Ertuğrul sailed up to Çengelköy and anchored by Dolmabahçe Palace. After the welcome ceremony in Dolmabahçe Palace, everyone present proceeded to the Muayede Salonu (Ceremonial Hall). A grand torchlight procession was organized by Dolmabahçe Sarayı accompanied by numerous steamboats and rowboats on the night of 1 July.

Committees came from other provinces to pay a visit to Dolmabahçe Palace as well. A committee arriving on the steamboat Marmara to extend the respects of the people of Balıkesir on 2 July 1927 was admitted to Dolmabahçe Palace. The committee from Kırklareli extended their respects to Mustafa Kemal Pasha and asked him to visit their city.32 In addition, Süleyman Sami Bey, governor of Istanbul, introduced the French consul of Istanbul to Gazi Mustafa Kemal on the official reception night on 2 July; other consuls also had the opportunity to meet Gazi. Foreign representatives participated in the celebrations in Istanbul as well and illuminated their buildings.33 The Committee of the Women’s Union paid a visit to Gazi Pasha on 3 July.34 A committee led by Hakkı Tarık Bey, Giresun deputy, on behalf of the Teacher’s Union on 7 July 1927, offered their respects to the president of the Republic in Dolmabahçe Palace. The meeting lasted for approximately an hour and a half. The committee consisted of Nureddin Ali Bey, rector of Istanbul University, Neşet Ömer Bey, dean of the Faculty of Medicine, Habib Bey, director of education, and Nakiye Hanım, director of the Feyziye School.35 Visitors included the representatives of a friendly country present on 10 July 1927. A delegation representing Afghanistan—including Mahmud Tarzi Han, that country’s minister of foreign affairs, Nebi Han, ambassador to France, and Gulam Ceylani Han, ambassador to Turkey—visited Dolmabahçe Palace.36 Local and foreign delegations continued to visit the palace for three months. Gazi allocated a part of his busy schedule to receiving these visits.

Mustafa Kemal Pasha visited official institutions in Istanbul whenever he found the opportunity. He also made short visits to nearby districts by car or motorboat through the Bosphorus late at night in order to relax and renew his energy after a difficult day. The president also made some official visits in the second week of July. After paying a visit to the Army Corps command, government office, and municipality on 7 July 1927, Gazi Pasha stopped by Şehitlik, Bakırköy, and Baruthane as well.37 Resuming his official contacts on the following day, Gazi went to the Istanbul headquarters of the Cumhuriyet Halk Fırkası (Republican People’s Party) and the Istanbul branch of the Tayyare Cemiyeti (Turkish Aeronautical Association).38 When he had the chance, he traveled to Kalamış on the motorboat Ankara in the evening on 11 July and returned to the palace within a short time. Present in his study the whole day on 14 July, Gazi Pasha sailed to Büyükada on the motorboat Ankara and visited the yacht club and returned on the same boat after spending time in public. In the following days, Gazi occasionally sailed at night on the Bosphorus and traveled to the shores of Yeşilköy, Florya, and Kavak.

Following the arrival of Prime Minister İsmet Pasha in Istanbul on 1 August upon invitation, deputy elections were among the issues to be discussed. They collaborated on the elections frequently in Dolmabahçe Palace. Consequently, candidates nominated by the president were elected all over the country and became deputies.

The great fire of Üsküdar on 23 August 1927 was a tragic event that took place during this time in Istanbul. Starting in Valideatık neighborhood, the fire spread quickly and destroyed 300 residences, six stores, a police station, a mosque, and a masjid within five fours. Gazi Pasha ordered the authorities to take all necessary measures, and the head assistant to the president, Rusuhi Bey, inspected the fire scene and expressed the president’s condolences to Üsküdar residents.39 Gazi Pasha also began an aid campaign by donating 5,000 liras for the fire victims.40 The Istanbul municipal government and the Red Crescent (Hilal-i Ahmer) mobilized to meet the victims’ food and shelter needs. Assistance was provided for officers whose residences had burned, including paying their September salaries early. Nevertheless, it was not possible to recover from the consequences of such a great fire. At the beginning of September, Gazi left the palace through the garden gate by the clock tower in the evening and walked the tram street. Seeing the president among them at the busiest hour of the day, the public applauded Gazi, and he responded to their cheering with a greeting.41 Gazi Pasha carried out a long program of visits that involved interacting with the public on 11 September, when he was driven to Taksim, Şişli, and Hürriyet-i Ebediye Hill via Beşiktaş and Akaratler Street. Upon his arrival at Hürriyet Hill, he paid his respects to the martyrs and conversed with the public while walking. When Gazi arrived at the tram stop in Bomonti, he rode the first second-class tramcar that arrived at the stop and traveled with the public, paying for his tram ticket personally. Gazi Pasha got off at the Tokatlıyan Hotel. He proceeded to Karaköy on a second-class tram from Tünel, reached Beyazıt by driving across the bridge, and arrived at the palace at night.42

Completing his work entitled Nutuk (The Speech), which related the history of the Turkish revolution and proposed new goals for the Turkish nation, was one of the highest priorities for Gazi in his study at Dolmabahçe, and Nutuk was ready in mid-September. Press reports indicated that Gazi would depart from Istanbul in October, and it was considered a certainty that the Congress of the Cumhuriyet Halk Fırkası would be opened with Nutuk in Ankara on 15 October.43

In the last days of his Istanbul visit, Mustafa Kemal Pasha continued making short visits in the city. Leaving the palace on the night of 13 September, Gazi went to İstinye via Ortaköy, Arnavutköy, Bebek, and Rumelihisarı Road, despite İsmet Pasha’s company, and arrived in Beyoğlu via Maslak Road. Gazi and his company walked for some time, rested at Lebon Patissarie, and later returned to Dolmabahçe. Gazi drove to Florya on the evening of 15 September. Resting in a refreshment bar, he returned to Sirkeci on the public train from Hadımköy and arrived at Dolmabahçe Palace by car via Galata, Beyoğlu, Şişli, and Akaratler.44 Gazi did not step outside on the last days of September as the departure date drew closer. He walked in the palace garden on the night of 23 September and sailed on the Bosphorus on the yacht Söğütlü for a short time. On 24 September he traveled to Moda on the motorboat Ankara. President Gazi Mustafa Kemal Pasha completed his first Istanbul visit on 30 September 1927 and left the city. He sailed to Mudania first and later to Bursa on the steamboat İzmir. Resting in Bursa for several days, he returned to Ankara on 10 October 1927 to restart his busy schedule. Undoubtedly, the 1927 visit of Mustafa Kemal Pasha occupies an important place among his Istanbul visits. During this visit, Gazi worked relentlessly and completed work on Nutuk. He followed the 1927 deputy elections from Istanbul.

Another tragic event during that time was the great fire in Üsküdar. Gazi Pasha pioneered an aid campaign again and made efforts to ease the distress of the Üsküdar residents. He met numerous committees and hosted some foreign representatives. After his 1927 visit, Gazi Pasha visited Istanbul at least once a year, and Istanbul became his most-visited city. His twenty-fifth and final visit to the city as president was on 27 May 1938. He was gravely ill during this period, and passed away in Istanbul on 10 November 1938.

Alphabet Reform

The alphabet issue also came to the forefront during the Ottoman Era. One of the important personalities of the Tanzimat Era, Münif Pasha, asserted at a conference in 1862 that the Arabic alphabet should be reformed. Münif Pasha’s conference presentation and article, entitled “The Problem of Orthography” and published in the journal Mecmua-ı Fünun, was highly influential in discussions on this issue. Exchanges of letters among intellectuals continued during the Tanzimat. Two approaches were advocated: using Latin letters instead of Arabic ones, and preserving but reforming Arabic letters. This discussion occupied the agenda during the Meşrutiyet (constitutional monarchy) period. An alphabet reform was considered during World War I by Enver Pasha, and writing Ottoman letters uncombined (huruf-ı munfasıla) was attempted for the first time. This reform was not adopted by the Ministry of National Education. It was used by the First Army for military correspondence, but this attempt failed.

A proposal regarding the adoption of Latin letters submitted in the İzmir Congress of Economy following the National Struggle raised the alphabet issue again. However, the issue was not allocated any space in the agenda by the Congress chair, Kazım Karabekir Pasha. Intense discussions and assertion of the Latin alphabet as a critical option occurred in 1924. Addressing TBMM, Şükrü Saraçoğlu, a deputy representing İzmir, called in a speech for the Latin alphabet to be adopted. The alphabet issue transformed into a matter for scientific discussion between 1924 and 1928.

The adoption of Latin numerals on 28 May 1928 was a development that foreshadowed the adoption of Latin letters. A committee was formed during negotiations on the adoption of Latin numerals, tasked with “considering the configuration and implementation of Latin letters in our language.” The Language Committee commenced its activities in July 1928.

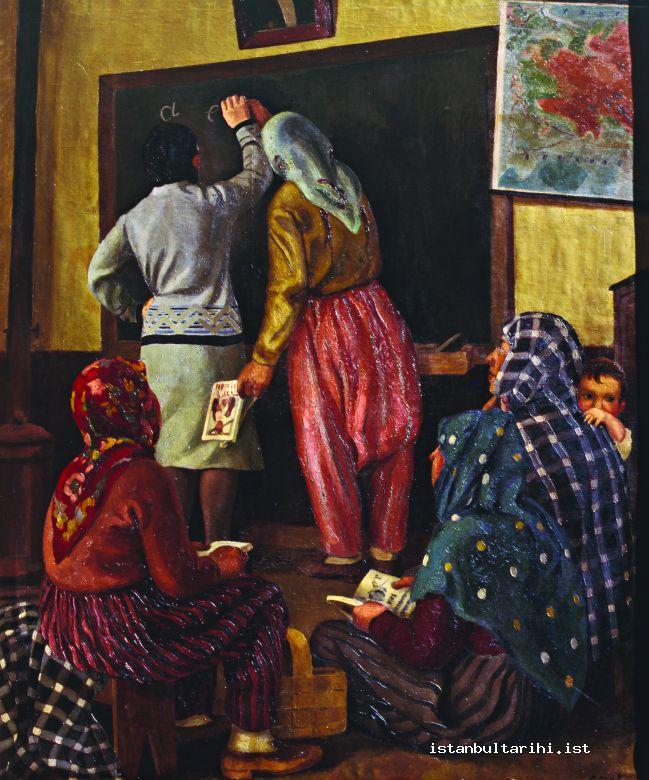

President Mustafa Kemal Pasha observed the alphabet discussions but did not take a position. However, he expressed his opinion to the Language Committee before leaving for Istanbul from Ankara. In the beginning of August 1928, the Language Committee arrived from Ankara to Istanbul and continued their work by consulting Mustafa Kemal Pasha daily. Mustafa Kemal penned a letter to Prime Minister İsmet Pasha in the new alphabet on 5 August 1928. This signaled that it was time to make the alphabet reform public. This declaration was made in a speech by the top authorized person for the first time in Gülhane—a speech that is acknowledged to have launched the alphabet reform. Selection of Gülhane Park for this event was undoubtedly not coincidental. The historically important Gülhane Hatt-ı Hümayunu (Imperial Edict of Gülhane) was declared there in 1839. Istanbul served as the center of the Turkish press. A university was located there, and it was considered the city of culture and science. Therefore, it was the most appropriate place to launch this significant cultural reform. Istanbul was also the center of support and dissidence for the alphabet reform. Mustafa Kemal Pasha planned to enact this reform in 1928 during his journey to Istanbul and to observe the developments personally.

Departing from Dolmabahçe Palace on the Ankara on the night of 9 August 1928, Mustafa Kemal Pasha cruised in the Marmara Sea for some time and proceeded to Gülhane Parkı, where the Republican People’s Party had organized a public concert, toward midnight. In the following hours, he made a speech announcing that the new Turkish letters had been adopted and that he would like all citizens to learn them in due course. The new Turkish letters referred to in this speech were the product of the alphabet project conducted by the Language Commission. The Gülhane speech of Mustafa Kemal could not be published on 10 August; however, it appeared in the newspapers under grand headlines on 11 August, such as “Great Speech by Great Gazi: Nutuk as the Text Announcing the Adoption of Our New Letters.”45 Another newspaper on the same date provided the speech text in the new alphabet under the headline “Gazi’s Speech” and wrote that all citizens should immediately learn the new Turkish letters.46 The alphabet reform constituted the primary agenda for the press and public alike; articles were published in newspapers; lessons started to be published in the new alphabet. Newspapers started reserving space for news in the new letters, and there was an increase in the number of columns written in this style. Mustafa Kemal Pasha desired that statesmen and authorities should learn the new alphabet in due course to serve as examples to the public. Therefore, a group including close friends of Gazi and a small number of deputies were given an alphabet lesson. It was decided on 25 August 1928 that deputies present in Istanbul join the conferences in Dolmabahçe Palace. The deputies were required to study and come to the conference ready. The invitation read “honoring the conference having learned the new Turkish letters.”

As instructed, 80 deputies went to Dolmabahçe Palace and started taking lessons in the new alphabet. This situation was described by the foreign press under the headline “Deputies Go to School.” The meetings between 25 and 29 August 1928 were referred to as conferences in the press while they constituted a congress in reality. The purpose of this event was to illuminate, convince those who could not comprehend the meaning of this de facto but non-enacted reform, and confirm the new alphabet. Humorous articles in the foreign press reflected the reality, since deputies actually became students. Deputies read extracts from the alphabet book, and some were required to write the new letters on the blackboard. Mustafa Kemal Pasha acted as a teacher, giving lectures and examining the deputies. For this reason, he was endowed with the title of Head Teacher. Courses and public schools (millet mektepleri) were opened all over the country to teach the new alphabet. The Head Teacher title of Gazi took its place among official records. Article 4 of the Millet Mektebi Teşkilatı (Public Schools Organization) stipulated the following: “Titles of Organization President and Public School Head Teacher are accepted by President Gazi Mustafa Kemal Pasha.” The alphabet reform was a crucial cultural movement that began in Istanbul and was dedicated to the people. Following his departure from Istanbul, President Mustafa Kemal continued teaching the new alphabet during his domestic visits. Finally, the Law Relating to Adoption and Implementation of Turkish Letters was enacted on 1 November 1928. On 2 November, newspapers reported this under the headline “TBMM Adopted New Letters Law.”47

Death of Atatürk

Atatürk experienced many health problems beginning at a young age. He underwent treatment for kidney problems at the Karlsbad baths toward the end of World War I. After he went to Anatolia during the National Struggle, his kidney problems persisted. He also had two heart attacks, in 1923 and 1927, and suffered from pneumonia in autumn 1936. Frequent nosebleeds and itching were the first symptoms of liver failure. Atatürk’s illness was understood to be serious in winter 1937 and was diagnosed at the beginning of 1938. Despite instant intervention, Atatürk died in Dolmabahçe Palace on Thursday, 10 November 1938 at 9:05.

Upon Atatürk’s death, the presidency flag at the palace was lowered to half-staff. At 11:25, all flags were lowered to half-staff. Photographs and news articles reflected the grief of people from all walks of life.

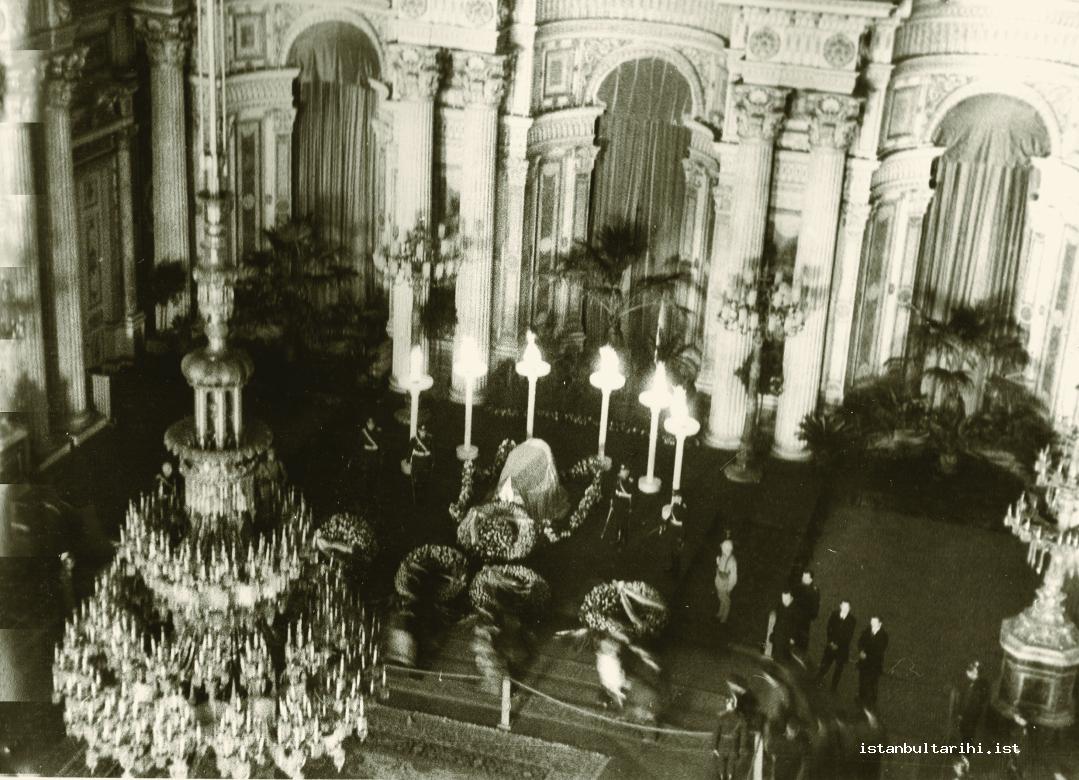

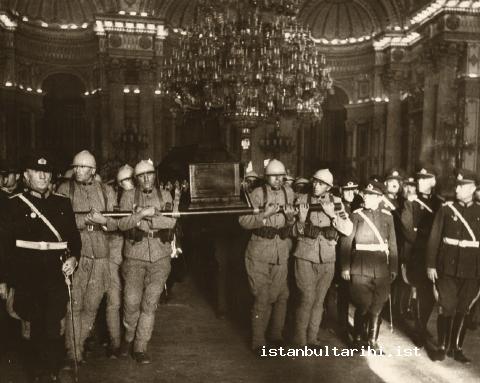

Atatürk’s body was embalmed before the funeral on 11 November 1938 but remained in his bedroom through 13 November. His coffin was placed on a catafalque in the ceremonial hall of Dolmabahçe Palace on 14 November. In the meantime, gathering under the leadership of President İsmet İnönü on 13 November, it was agreed that Atatürk would be placed in the Museum of Ethnography in Ankara until a suitable mausoleum could be built. The funeral program included the following details: opening Atatürk’s catafalque to the public for three days beginning 16 November 1938, reception of the coffin from Dolmabahçe Palace at 8:30 on 19 November 1938, funeral procession, travel by the battleship Yavuz to İzmit, travel from İzmit to Ankara, welcome, procession from parliament to the Museum of Ethnography, and transfer of the coffin to the Museum of Ethnography on 21 November. It was decided that flags would be lowered to half-staff until midnight on 21 November. The catafalque viewing in Dolmabahçe Palace commenced at 10:00 on 16 November 1938. Placed on the catafalque, the coffin was covered with a Turkish flag. Istanbulians started visiting at 12:00 after a visit by dignitaries. On the following day, the press reported the number of visitors as 150,000. This number increased on 17 November. According to some journalists, 180 people passed through the grand hall gate per minute early in the morning, and this number rose to 250 people per minute in the following hours, including during the night. Tragically, 11 people were crushed to death and 40 were wounded during a stampede among 100,000 visitors around 20:00 on 17 November. Among those losing their lives were non-Muslim citizens. This situation demonstrated the deep grief of all citizens over Atatürk’s death. The stampede culminated in a saddening event, which was feared by the government. Results of the autopsies indicated that the deaths were caused by respiratory insufficiency. The incident was attributed to negligence, including the lack of a police line-up and continued operation of the trams bringing people to the viewing site in spite of the crowding. Newspapers did not publish any news or commentaries about the event except for the government notice. An investigation revealed that reopening the leaves of the gate by the clock tower and crowding in this direction had caused the disaster.48 The tragedy became known as the Dolmabahçe Stampede, and the court procedures regarding the officials had widespread media coverage.

The catafalque viewing resumed on 18 November and ended at midnight. Prime Minister Celal Bayar arrived in Istanbul on 18 November for the ceremony preceding Atatürk’s transfer to Ankara. The location of Atatürk’s funeral prayer became another issue. The government did not favor the idea of a funeral prayer at the mosque due to concern about the potential for undesired incidents. Consulted for his opinion on the matter, Prof. Dr. Şerafettin Yaltkaya, a member of the faculty at the Islamic Studies Institute at Istanbul University, said that there was no requirement to transfer the body to a mosque for the funeral prayer, while Rıfat Börekçi, director of religious affairs, remarked that the funeral prayer could be performed anywhere. On 19 November 1938 at 8:10, the coffin was placed on two tables under the big chandelier in the middle of the room and Prof. Dr. Şerafettin led the funeral prayer. All fellow fighters of Atatürk and some deputies and doctors were present at the funeral prayer. Following the prayer, the coffin was taken out at 8:21 and placed on a gun carriage pulled by four black stallions. Upon a signal from Galata Tower, an artillery salute was performed.

The funeral procession followed the tramline passing through Tophane, Karaköy, and Eminönü Square, through the bridgeway and Gülhane Park, over Bahçekapı, Sirkeci, and Salkımsöğüt. Mounted police, who led the way and kept the road open, were followed by a cavalcade carrying spears, an infantry battalion led by a band, and a navy battalion, also led by a band. Next came university students and military officers bearing wreaths; Atatürk’s coffin followed the wreaths. The funeral procession—which included generals, consuls, civilian and military dignitaries, and representatives of numerous organizations—was more than 2 kilometers long. Planes flew overhead as well. When the procession reached Sarayburnu through the park road, it was 12:26. The press reported the number of mourners at 600,000. Without doubt, 19 November 1938 was a historic day for Istanbul.

Atatürk’s coffin was transferred from Sarayburnu to the torpedo boat Zafer and from there to the battleship Yavuz. Taken to İzmit by the Yavuz, the body reached Ankara by train on 20 November. Following the placement of Atatürk’s coffin in the catafalque set up by the parliament, he was transferred to the Museum of Ethnography with an official ceremony on 21 November and stayed here until he was transferred to the mausoleum in 1953.

Events of 6–7 September 1955

It is not possible to evaluate the events that took place in Istanbul and İzmir on 6–7 September 1955 without reference to the Cyprus dispute. Developments in Cyprus render the process comprehensible. The Turkish government did not have a proactive policy regarding Cyprus, one of the most significant problems of Turkish foreign policy, in the first half of the 1950s. As Turkey was considering immediately joining NATO against the USSR threat, it might be probable to fathom this situation until its NATO membership in 1952. Until this date, all requests regarding the hand-over of Cyprus to Greece were rejected by Britain, and it was made clear by Britain that there was no change in the status of the island. Nevertheless, Turkey appeared to be relieved by Britain’s attitude in relation to this development. Moreover, since Turkey focused on the signing of the Balkan Pact, it avoided any intervention in Cyprus which might lead to disputes with Greece. While Turkey assigned utmost importance to the signing of the Balkan Pact on 9 August 1954, Greece did not step back from its requests on Cyprus. Greece applied to the United Nations for self-determination for Cyprus on 16 August 1954. However, the United Nations declined to give a decision following an examination of the matter. Greece’s best diplomatic efforts had yielded no results.

During this period, several developments were taking place in Turkey. A committee was established to communicate and support the Cyprus dispute on 28 August 1954; committee leaders visited Prime Minister Adnan Menderes shortly thereafter. Menderes reiterated during this visit that they would not make any concessions with respect to the Cyprus dispute. The committee took the name Cyprus is Turkish Association (Kıbrıs Türktür Cemiyeti) in October 1954 and tried to defend the Cyprus dispute through propaganda.

Significant developments took place in Cyprus in 1955. While the Greek terrorist organization, EOKA, and protests broke out in spring 1955 in Cyprus against the British administration of the island, Cypriot Turks soon became the target of EOKA. Upon the exasperation of the events, the British government invited Turkey to a conference in London on 29 August 1955 to negotiate the matter. This was an important milestone for the Cyprus dispute.

The activities of the Cyprus is Turkish Association escalated in August. Dr. Fazıl Küçük, leader of the Cypriot Turks, wrote a letter stating that Turks were living under a threat of massacre. This letter had wide repercussions. Burning of Greek newspapers in Istanbul took place with the order of the association to support a demonstration by the association’s London branch on 4 September 1955, and it had a tremendous impact. The demonstration was carried out during the London conference and generated substantial support. New association branches were opened in various cities on 5 September following the demonstration; the number of these branches rose to 135. The London demonstration had already escalated tensions over Cyprus. The Istanbul Union of Workers’ Syndicate stated in a telegram that 180,000 workers in Istanbul were at the disposal of the association. Association president Hikmet Bil stated in his memoirs that he had a meeting with Prime Minister Adnan Menderes on 5 September 1955. Menderes received a telegram from Fatin Rüştü Zorlu (who was in London) stating, “I am in a weak position. I must be able to say ‘we cannot restrain the Turkish public.’ You should act more proactively.” Association President Bil met Turkish President Celal Bayar, Prime Minister Adnan Menderes, and Minister of Interior Namık Gedik in Florya on the night of 5 September and planned a support manifestation. Contrary to statements by Hikmet Bil, Ahmet Emin Yalman stated that the telegram said to have arrived from London did not exist in the archive of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Nonetheless, it is understood that a controlled support rally was planned by some organizations. It was obvious that they wanted to give a clear message to Greece and the Greek community in Turkey. The demonstration going out of control constituted a serious problem. In fact, this situation should have been foreseen, as the psychological environment necessary for provoking and directing the masses appeared to develop.

Radio news reported at 13:00 that windows of Atatürk’s childhood home in Selanik had been damaged by a bomb thrown into its garden. At 16:00 the same day, the Istanbul Express published the news under the headline “Bomb to Atatürk.” The print news was based on the radio news, the events were exaggerated by both sources, and thus the situation fomented great rage among the public. In the meantime, some crowds had already started gathering on side streets in Beyoğlu, the starting point of the events. The Beyoğlu police chief notified the governor of possible breakouts. Warned by the governor, the city police chief responded that there was nothing to worry about and he was seeing off the president and prime minister to Ankara in the meantime. Meanwhile, the Cyprus is Turkish Association started protesting in Taksim against the bombing. A demonstration was held in front of the Republic Monument in Taksim at 17:20, and Turkish flags were hung on the monument. A large number of placards and flags were distributed to the public during the day. A group of people chanting slogans tried to reach the Greek Consulate, but they were dispersed by the municipal police. Another group broke the windows of the Greek high school. Witnesses of the 6–7 September events mentioned several mysterious situations, including men who provoked the crowd with fiery speeches and then disappeared. The number of people in Taksim swiftly rose to hundreds, and the crowds could not be controlled. The events quickly spread throughout Istanbul. Windows of Greek shops and stores in Beyoğlu and other districts were broken. While there was some damage at the beginning, the vandalism turned into looting throughout the night. Looting and attacks were carried out against not only the Greeks but also other minorities. Beginning in Beyoğlu, the events rapidly spread to other districts as well. Kurtuluş, Beşiktaş, Kumkapı, Bakırköy, Dolapdere, Arnavutköy, and Adalar, where many Greeks lived, were ransacked. The government, alarmed by the rapid spread of violence, ordered soldiers to shoot to prevent the events. Similar events took place in İzmir and Ankara. In İzmir, the newspaper Gece Postası wrote on 6 September that there should be no Greek flag in Konak. A crowd gathering afterward raided the Greek pavilion at the Izmir fair and burned it. Later in the evening, the Greek consulate in Alsancak was demolished. Looting took place in districts with a large number of Greek homes and businesses. Most of the rioting had been stopped by the military by midnight. Events in Ankara were less serious than in İzmir and Istanbul. Protesting students in Ulus Square were dispersed by the police. The small number of non-Muslim citizens in Ankara helped prevent the events from getting worse. There were small-scale protests in other cities. Events in Istanbul slipped out of control by 22:00 on 6 September with increasing levels of destruction. A newspaper dated 7 September observed the events minute by minute and reported that the bombing of Atatürk’s house in Selanik was first noticed between 15:00 and 17:00. The youth started marching toward Taksim at 17:20, and the first demonstration took place in front of Hagia Triada Church at 17:50. Following the first attack on the Greek shops on İstiklal Street at 18:05, stores between Taksim and Tünel were attacked until 19:00. By 19:30 demonstrations had started in Karaköy, Tarlabaşı, and Sirkeci; attacks occurred in Bakırköy, Yeşilköy, and other suburban areas at 21:00. At midnight, martial law was declared, and the rioting was brought under control with the help of military units around 2:30 the following morning.49

A total of 5,104 individuals in Istanbul, 300 in Ankara, and 170 in İzmir were apprehended following the declaration of martial law. According to the first statement by the government, the youth had demonstrated to protest the bombing in Selanik, and Communists, taking advantage of this disturbance, looted and destroyed the neighborhoods. Most of the detainees were eventually found not to have participated in the rioting and were released in December 1955. It also appeared that some left-leaning people and communists were arrested based on a list prepared earlier, as the list included the names of people who had died long before or were still doing their military service. The government shut down the Cyprus is Turkish Association due to the 6–7 September events.50 The Minister of Interior, Namık Gedik, resigned on 9 September.

During the rioting, a priest died and 30 civilians were injured; 4,340 stores, 110 hotels and restaurants, 27 pharmacies, 21 factories, three Greek newspapers, 52 Greek schools, eight Armenian schools, 2,600 homes, 73 churches, eight hagiasmas (holy wells or springs), one synagogue, and two monasteries were damaged and looted. Most looted properties belonged to the Greeks; the rest were Armenian or Jewish properties. On 11 September 1955, an aid committee was formed under the auspices of the president and with the voluntary leadership of the prime minister, and a major aid campaign began. Citizens numbering 4,433 declared 69,578,744 liras worth of damage. The aid committee tried to meet these losses through Law no. 6684, enacted in 1956.

The events of 6–7 September remained on Turkey’s agenda as a top matter for months, leading to long discussions in parliament. The opposition party accused the government of not taking sufficient precautions in time. The inefficiency of the police department, lack of coordination, and late intervention by the military came in for substantial criticism. The government, however, asserted in group and parliament that the communists were effective in the events.

The Greek press tried to hold Britain responsible for these events. Turkey and Greece confronted one another over the Cyprus problem, and serious tensions arose between two countries in the following years.

Coup d’État on 27 May 1960

The Democratic Party won the 1950 elections and had even greater success in 1954. The opposition Republican People’s Party only had 31 deputies in the parliament. Although the Democratic Party retained power in the 1957 elections, the Republican People’s Party strengthened, with the Democratic Party obtaining 424 deputies and the opposition 178. Economic problems were on the rise during the last part of the Democratic Party’s time in power. Exports and investments came to a halt due to a foreign currency bottleneck in mid-1958. Existing facilities could not be run, either, due to the lack of financing. This caused shortages in goods, an increase in inflation, and widespread unemployment. To overcome these problems, the Menderes government put stabilization measures into effect in August 1958. These measures appeared to have ostensible contributions; however, hoped-for additional aid and credits from the West, particularly the United States, could not be obtained. Therefore, the government started barter trade with Eastern-bloc countries by necessity. The country experienced high inflation due to the low growth rate since 1954. The stabilization measures of 1958 actually amounted to ringing alarms in the economy. These economic hardships were also reflected in politics. The tension between the government and the opposition increased.

In autumn 1958, Adnan Menderes asked citizens to form the Homeland Front (Vatan Cephesi) to oppose Republican People’s Party leader İsmet İnönü, who was planning to create the National Opposition Front (Milli Muhalefet Cephesi) in cooperation with other opposition parties in the parliament. The Great Offense (Büyük Taarruz) tours, led by İsmet İnönü and accompanied by the party members and journalists on 19 April 1959, caused the political atmosphere to become even more intense; this expression actually denoted the final Turkish attack that had ended the Greek invasion of Anatolia in 1922. During these tours, a stone hit İsmet İnönü. Moving from Uşak to Manisa and İzmir, İnönü arrived in Istanbul on 4 May 1959. When he departed from Yeşilköy Airport for the city center and Topkapı, he was attacked by a group of 10 to 15 people. The car he was in was kicked, its windows were broken, and some people climbed on top of the car. As the police did not take sufficient measures to intervene in the attacks, a cavalry commander passing by with his soldiers dispersed the attackers and perhaps prevented worse violence. Referred to as the Topkapı events, details of this incident were not reported in the press the next day due to a news sanction. However, a newspaper released an issue with the headline “A New Press Sanction” the following day. The newspaper stated below the headline that there were ongoing preparations relating to events that occurred during the arrival of İsmet İnönü in Istanbul that and statements about the events were forbidden.51 Incidents taking place in September 1959 in Çanakkale and February 1960 in Konya aggravated the existing tension. Some incidents occurring during the spring 1960 visit of İsmet İnönü to Yeşilhisar and Kayseri reduced even further the possibility for communication and consensus between the government and the opposition. Events of April 1960 played a determinant role in the destiny of the Democratic Party. In a meeting of the Democratic Party on 7 April 1960, it was reiterated that strict measures should be taken against the opposition planning to overthrow the government by force. A consensus was reached in the party’s 18 April meeting that a parliamentary inquiry commission (tahkikat komisyonu) must be established. This decision was the trigger for upcoming events. The first student demonstrations started in Kızılay, Ankara. Demonstrations supporting İnönü in Kızılay soon turned into protests against the government. One journalist and 21 students were detained; five of these detainees were apprehended in the clash between the police and demonstrators.

A draft bill relating to the Inquiry Commission was passed on 27 April 1960. Speeches about the law in parliament further sharpened existing tensions. Republican People’s Party leader İsmet İnönü finished his address stating, “Should you insist on this path, I cannot save you either.” According to Metin Toker, this address was a declaration that the time was ripe for a coup d’état in Turkey. Information about the adoption of the draft bill authorizing the Inquiry Commission, and an attendance ban on İsmet İnönü for 12 sessions because of his address, reached Istanbul immediately. Preparations began for protests to take place on 27 April by Istanbul youth branches of the Republican People’s Party. According to the memoirs of the professor of constitutional law at Istanbul University, Ali Fuat Başgil, who was revered by Prime Minister Menderes and was the government’s legal advisor, the events at Istanbul University were triggered by student protests on 28 April 1960 at 10:00. A speech was addressed by the Faculty of Law, and demonstrations commenced. After the police failed to intervene sufficiently in the student demonstrations, a military corps waiting by the grand entrance stepped into action in order to bring the students under control. Observing the developments from his university office with concern, Başgil witnessed soldiers, students, and military officers hugging when they met. This was an important moment for Başgil and demonstrated that “the movement spread to the military and the Menderes government was falling.” Prof. Dr. Sıddık Sami Onar argued with police officers and fell, breaking his glasses and injuring himself; this incident also escalated the events. While student protests in Beyazıt Square continued, Turan Emeksiz, a forestry student, died after being hit by a ricocheting bullet, and a high school student was accidentally run over by a tank. These incidents rendered the process uncontrollable. A total of 40 people, 16 of them police officers, were injured in the events. As events expanded into Laleli, a pharmacy named Menderes Eczanesi and a building with the nameplate Vatan Cephesi (Homeland Front) were destroyed. Students boycotted the lectures at Istanbul Technical University and demonstrated on the same day. Student demonstrations also took place at the Istanbul Faculty of Medicine. Consequently, approximately 150 students were detained. At the suggestion of Istanbul Governor Ethem Yetkiner, the government imposed martial law at 15:00 in Istanbul and Ankara. Under the headline “Martial Law” on 29 April, the newspapers reported that publishing information about the events was banned, any kind of meeting was forbidden, and entertainment venues were closed.52 The declaration of martial law could not, however, prevent student protests. Starting on 29 April at the Faculty of Law in Ankara, the protests quickly spread to the Faculty of Political Science. On 30 April, newspapers reported the closure of universities and colleges in Ankara for a month.53

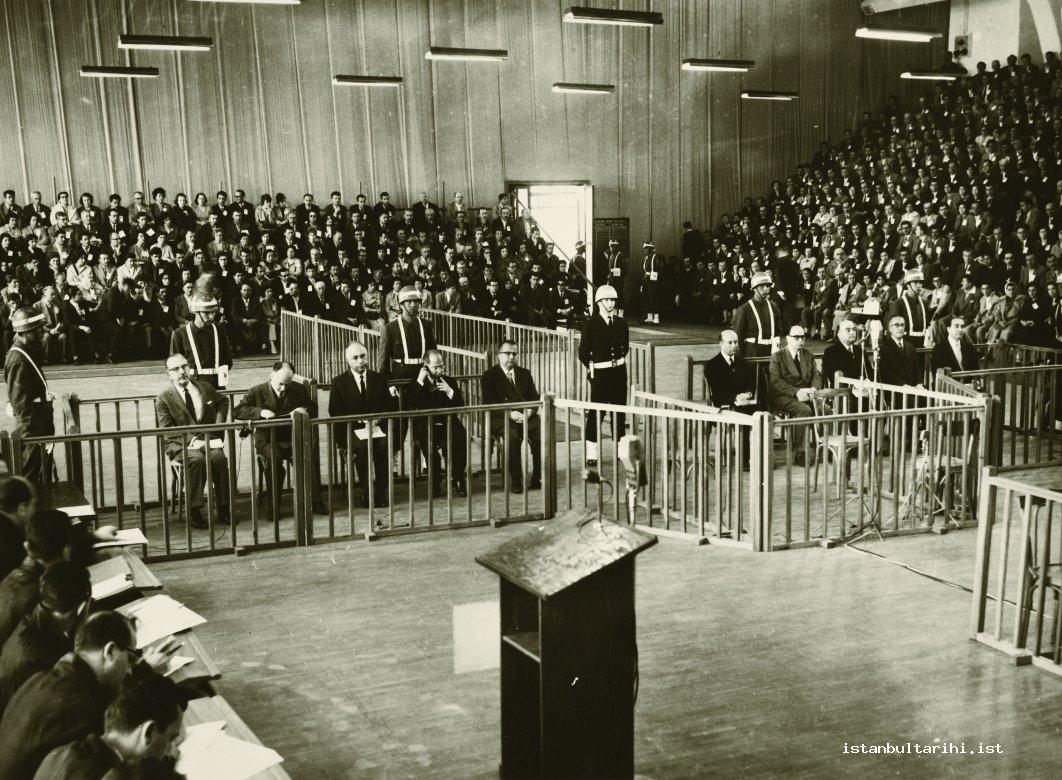

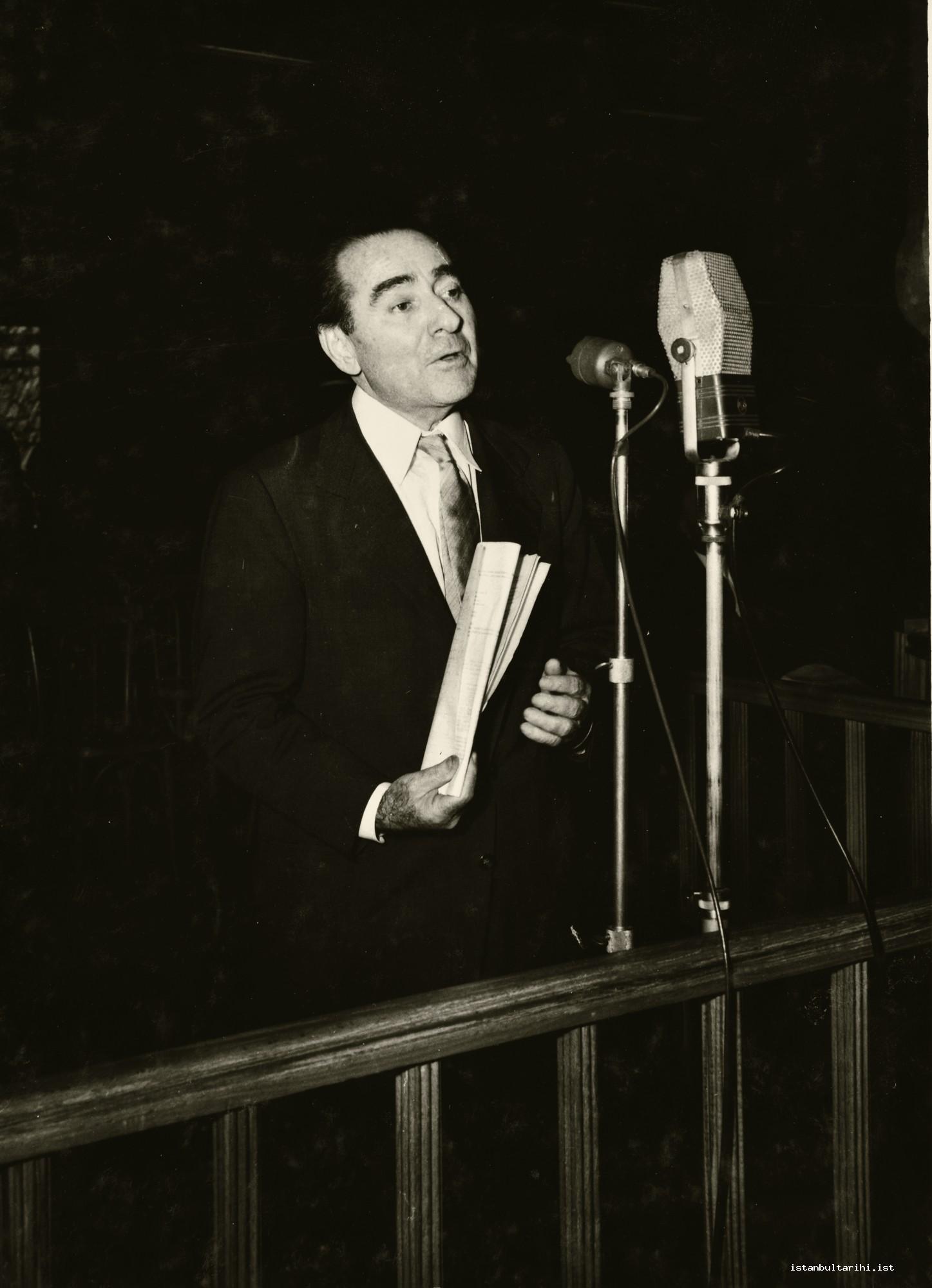

Events in Istanbul continued on 30 April 1960. A student named Nedim Özpolat was killed during demonstrations in Sultanahmet Square. As before, a publication ban was imposed. In fact, these publication bans worked against the government, since rumors exaggerated the problems. In order to prevent the events, the martial law commanderships forbade all meetings and demonstrations both indoors and outdoors. A curfew was imposed from 21:00 to 5:00. Events in Istanbul and Ankara had an impact on government policy. A declaration by Prime Minister Adnan Menderes abolishing the Inquiry Commission came too late and could not prevent the military intervention. The Democratic Party era ended with the coup d’état on Friday, 27 May 1960. The National Unity Committee (Milli Birlik Komitesi) formed by the coup leaders took over the administration on 27 May. On 14 October, trials of Democratic Party leaders began on Yassıada Island by the Supreme Court of Justice, which included members selected by the National Unity Committee. As a result of the trials, Fatin Rüştü Zorlu and Hasan Polatkan were executed on 16 September 1961 and Adnan Menderes on 17 September 1961. Numerous other Democratic Party leaders were sentenced. A major purge of the army was undertaken by the National Unity Committee, and many military officers were forced into retirement. Furthermore, 147 faculty members, most from universities in Istanbul, were removed from office on the grounds that they opposed reforms.

Coup d’État on 12 September 1980

The National Unity Committee took over the administration of the coup on 27 May 1960. The first general elections following the coup took place in 1961. A coalition government by the Republican People’s Party and the Adalet Partisi (Justice Party) was formed on 21 November 1961 as a result of this election. This coalition government did not last long, and political stability could not be restored with the governments that followed, either. Called the undecided governments period, this persisted until 1965 when the Justice Party won enough votes to rule alone.

The youth rebellion that began in France in 1968 found a voice in Turkey; protests on education-related issues started at Ankara University and spread to Istanbul, and students prevented exams from being held by occupying the rectorate and the senate hall following their decision for boycotting at the Faculty of Law on 12 June 1968. The occupation and boycotts ended as soon as the university administration agreed to student requests on 22 June. The university reopened on 27 June, and exams were scheduled to start on 15 July. Summer 1968 was tumultuous for Istanbul. The visit by the United States Sixth Fleet to Istanbul on 15 July was protested by students of Istanbul Technical University. A hotel that housed American soldiers was stoned on 16 July. On 17 July the police raided the Istanbul Technical University student dormitory to detain those involved in the events. A large number of students and policemen were injured in the events. This incident exacerbated the protests. Descending to the port of Dolmabahçe, students beat the American soldiers they encountered and threw them into the sea. The death of student Vedat Demircioğlu, who received a head injury during the Istanbul Technical University student dormitory raid, brought about another wave of protests. These events were regarded as an indicator of anti-Americanism. Another visit by the Sixth Fleet in February 1969 evoked new protests. On Sunday 16 February, two people were killed and 114 wounded in a conflict between leftists and rightists during the March Against Imperialism and Exploitation in Taksim. This “Bloody Sunday” served as a harbinger of future events.

Another intervention in democracy occurred on 12 March 1971. The government fell as a result of the memorandum of the armed forces. Martial law was declared in Istanbul and most cities, and a number of associations and newspapers were closed. Ziverbey Mansion in Istanbul became well known as the venue for the interrogation of left-wing intellectuals who were charged with a coup attempt. The period after 12 March 1970 and before 12 September 1980 was a period of weak governments and crises. Particularly the second half of the 1970s witnessed a number of political murders, disruption of social peace, and an increase in terrorism. Many citizens died and hundreds were injured when crowds gathered on Kazancı Yokuşu after people at the top of the Sular İdaresi Binası (Water Administration Building) shot at the crowd near the end of a speech by Kemal Türkler, chairman of the Confederation of Progressive Trade Unions, in Taksim Square on 1 May 1977. The Milliyet Daily reported on 3 May 1977 that 36 people had died; only two were killed by bullets, while the rest died in the resulting stampede. The reality could not be revealed despite various commentaries and assumptions relating to the perpetrators of the terrorist act. The massacre of 1 May was the first in a series of events leading to the 12 September military coup. Five citizens were killed and 44 wounded, five seriously, in a bomb attack on students leaving Istanbul University on 16 March 1978; the number of deaths rose to seven following the death of two wounded students later.

In autumn 1978, a platitude of political killings occurred, particularly in Istanbul. Murder of well-known public figures and other acts of terrorism could not be prevented despite all efforts, and politics proved to be helpless in general. Another problem was the division of the police into leftist and rightist camps. Political murders committed in Istanbul in 1978 included the killing on 4 October of Recep Haşatlı, Istanbul Chairman of the Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi (National Movement Party) in an ambush on his way home. The dean of the Faculty of Electrical Engineering, Ord. Prof. Dr. Bedri Karafakioğlu, was murdered on 20 October. Aggravation of events and its massive quality led to martial law in Istanbul in December 1978. Abdi İpekçi, the editor-in-chief of Milliyet Daily, was assassinated on his way home on 1 February 1979. Prof. Dr. Ümit Yaşar Doğanay of Istanbul University was killed on 20 November 1979. Prof. Dr. Cavit Orhan Tütengil, a writer at Cumhuriyet Daily, was murdered on 7 December 1979. İlhan Darendelioğlu, leader of the Associations for Struggle with Communism, editor-in-chief of Ortadoğu Daily, and a member of the Istanbul executive board of the National Movement Party, was assassinated on 19 November 1979, and on 4 April 1980, İsmail Gerçeksöz, the new editor-in-chief of the Ortadoğu Daily, was killed. Politicians and journalists from the left and right were killed, and the sociological and psychological conditions for a coup were emerging. The political killings did not stop in the following summer. Republican People’s Party Istanbul deputy Abdurrahman Köksaloğlu was killed in Şişli on 15 July. The assassination of the former prime minister Nihat Erim and his bodyguard in Kartal-Dragos was worrying evidence of the extent of terrorism. The assassination of Kemal Türkler, chairman of the Confederation of Progressive Trade Unions, on 22 July 1980, less than two months before the 12 September coup, had a heavily intimidating effect on the working class.

Social unrest reached a critical threshold in autumn 1980. No political solutions were found, and the parliament could hardly ever convene during this period for lack of a quorum. Despite the two-year-long martial law in Istanbul, terrorism and upheavals could not be prevented. There was no information regarding the coup d’état in Milliyet Daily on 12 September 1980, as it probably went to press early. The front-page news read that bomb placards were hung in 100 places within Istanbul and that four police officers were injured during the removal of these placards.54 Turkey experienced another coup d’état on Friday, 12 September 1980; the army took over the government. Parliament was adjourned and martial law was declared throughout the country. İsmail Hakkı Akansel, commander of the War Colleges and a lieutenant general, was appointed mayor of Istanbul, replacing Aytekin Kotil. Istanbul Governor Nevzat Ayaz remained in office, while General Necdet Üruğ, Commander of the First Army, became the Commander of Martial Law. The first general election following the 12 September coup occurred on 6 November 1983 and ANAP, led by Turgut Özal (d. 1993), formed a government. Nevertheless, a complete return to democracy took longer. Martial law in Istanbul was rescinded on 19 November 1985, and life started to gradually return to normal.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ahmad, Feroz and Ahmad Bedia Turgay, Türkiye’de Çok Partili Politikanın Açıklamalı Kronolojisi, Istanbul: Bilgi Yayınevi, 1976.

Akar, Atilla, Suikastler Cumhuriyeti, Istanbul: Profil Yayıncılık, 2010.

Albayrak, Mustafa, Türk Siyasi Tarihinde Demokrat Parti (1946-1960), Ankara: Phoenix Yayınevi, 2004.

Armaoğlu, Fahir, 20. Yüzyıl Siyasi Tarihi 1914-1980, Ankara: Türkiye İş Bankası Kültür Yayınları, 1988.

Artuk, Cevriye, “Atatürk’ün 1 Temmuz 1927 Senesinde İstanbul’a Gelişi”, IX. Türk Tarih Kongresi: Bildiriler, Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu,1989, v. 3, p. 2081 et seq.

Aydın, Mahir, İstanbul Kurtulurken: İstanbul’un Kurtuluş Bayramı, Istanbul: İlgi Kültür Sanat Yayıncılık, 2011.

Banoğlu, Niyazi Ahmet, Atatürk’ün İstanbul’daki Hayatı, II vol., Istanbul: Milli Eğitim Basımevi, 1973, vol. 1.

Baran, Tülay Alim, “İstanbul Basınında Cumhuriyetin İlânına Tepkiler ve Yorumlar”, Atatürk Araştırma Merkezi Dergisi, 1999, no. 44, p. 627-645.

Belen, Fahri, Türk Kurtuluş Savaşı, Ankara: Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı, 1983.

Boran, Tunç, “Atatürk’ün Cenaze Töreni: Yas ve Metanet”, Atatürk Yolu, 2011, no. 47, p. 490.

Burçak, Rıfkı Salim, On Yılın Anıları (1950-1960), Ankara: Nurol Matbaacılık, 1998.

Çavdar, Tevfik, “Demokrat Parti”, CDTA, VIII, 2060-2075.

Çelik, Âdem, “Harf İnkılabına Giden Süreç (1923-1928)”, master thesis, Marmara University, 2009.

Çoker, Fahri, “Hilâfetin Kaldırılması ve Hanedanın Yurtdışına Çıkarılması”, Toplumsal Tarih, 1999, no. 66, p. 4-11.

Dönmez, Cengiz, Tarihi Gerçekleriyle Harf İnkılabı ve Kazanımları, Ankara: Gazi Kitabevi, 2009.

Dursun, Davut, 12 Eylül Darbesi, Istanbul: Şehir yayınları, 2005.

Eroğul, Cem, Demokrat Parti Tarihi ve İdeolojisi, Ankara: İmge Yayınları, 2003.

Fedayi, Cemal, “Türkiye’nin Siyasal ve Sosyal Kaos Dönemi (1971-1980)”, Türkiye’nin Politik Tarihi, Ankara: Savaş Yayınevi, 2011.

Göktepe, Cihat, “Türkiye’de 27 Mayıs Darbesi Sonrası İç ve Dış Siyasi Gelişmeler (1961-1964)”, Türkiye’nin Politik Tarihi, Ankara: Savaş Yayınevi, 2011.

Gümüşoğlu, Hasan, Osmanlı’da Hilâfet ve Halifeliğin Kaldırılması, Istanbul: Kayıhan Yayınları; 2004.

Güven, Cemal, “Atatürk’ün Ölümü ve Cenaze Merasimi”, Selçuk Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi, 2000, special edition, pp. 114-133.

Güven, Dilek, “6-7 Eylül Olayları ve Failler”, Toplumsal Tarih, 2005, no. 141, pp. 38-49.

Hülagü, Metin, Yurtsuz İmparator Vahdeddin: İngiliz Gizli Belgelerinde Vahdeddin ve Osmanlı Hanedanı, Istanbul: Timaş Yayınları, 2008.

Kabacalı, Alpay, Geçmişten Günümüze İstanbul, Istanbul: Denizbank, 2003.

Nigar, Salih Keramet, Halife İkinci Abdülmecid, Istanbul: İnkılap ve Aka Kitabevleri, 1964.

Ökte, Ertuğrul Zekai, Gazi Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’ün Yurtiçi Gezileri (1922-1931), Istanbul: Tarihi Araştırmalar ve Dokümantasyon Merkezleri Kurma ve Geliştirme Vakfı, 2000, vol. 1.

Önder, Mehmet, Atatürk’ün Yurt Gezileri, Ankara: Türkiye İş Bankası Kültür Yayınları, 1998.

Öymen, Altan, Öfkeli Yıllar, Istanbul: Doğan Kitap, 2008.

Özcan, Besim, “Cumhuriyetin İlânı ve Yankıları”, Atatürk Üniversitesi Türkiyat Araştırmaları Enstitüsü Dergisi, 1999, no. 11, pp. 289-298.

Özkaya, Yücel, “Gazi Mustafa Kemal Paşa’nın 1927 İstanbul ve Sonraki Gezileri”, Atatürk Yolu, 1994, no. 14,p. 185

Özkaya, Yücel, “Türk Basınında Cumhuriyetin İlânının Öncesi ve Sonrası”, Atatürk Yolu, 1993, no. 11, p. 299.

Sakin, Serdar and Sabit Dokuyan, Kıbrıs ve 6-7 Eylül Olayları, Istanbul: IQ Kültür Sanat Yayıncılık, 2010.

Satan, Ali, Halifeliğin Kaldırılması, Istanbul: Gökkubbe, 2008.

Satan, Ali (haz.), İstanbul’un 100 Yılı, Istanbul: İstanbul Büyükşehir Belediyesi Kültür A.Ş., 2010.

Soyak, Hasan Rıza, Atatürk’ten Hatıralar, II vol., Istanbul: Yapı ve Kredi Bankası, 1973.

Şimşir, Bilal, Türk Yazı Devrimi, Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu, 1992.

Temel, Mehmet, İşgal Yıllarında İstanbul’un Sosyal Durumu, Ankara: T. C: Kültür Bakanlığı Yayınları, 1998.

Toker, Metin, Demokrasiden Darbeye 1957-1960, Istanbul: Bilgi yayınları, 1991.

Tokgöz Erdinç, “Cumhuriyet Döneminde Ekonomik Gelişmeler”, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Tarihi II, Ankara: Atatürk Araştırma Merkezi Yayınları, 2002.

Ülkütaşır, M. Şakir, Atatürk ve Harf Devrimi, Ankara: Türk Dil Kurumu yayınları, 1973.

Yalkın, Razi, “Son Halife Abdülmecid ve Hânedânı Âli-Osman İstanbul’dan Nasıl Çıkarıldı?”, Tarih Dünyası, 1950, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 22-23, 42; vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 58-61; vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 120-122; vol. 1, no. 4, pp. 165-167; vol. 1, no. 5, pp. 215-217; vol. 1, no. 6, pp. 261-262; vol.1, no. 7, pp. 305-306; vol. 1, no. 8, pp. 345-346.

Yücel, M. Serhan, Demokrat Parti, Istanbul: Ülke Kitapları, 2001.

FOOTNOTES

1 Tevhid-i Efkâr, 30 August 1923, no. 3825.

2 İkdam, 4 September 1923, no. 9490.