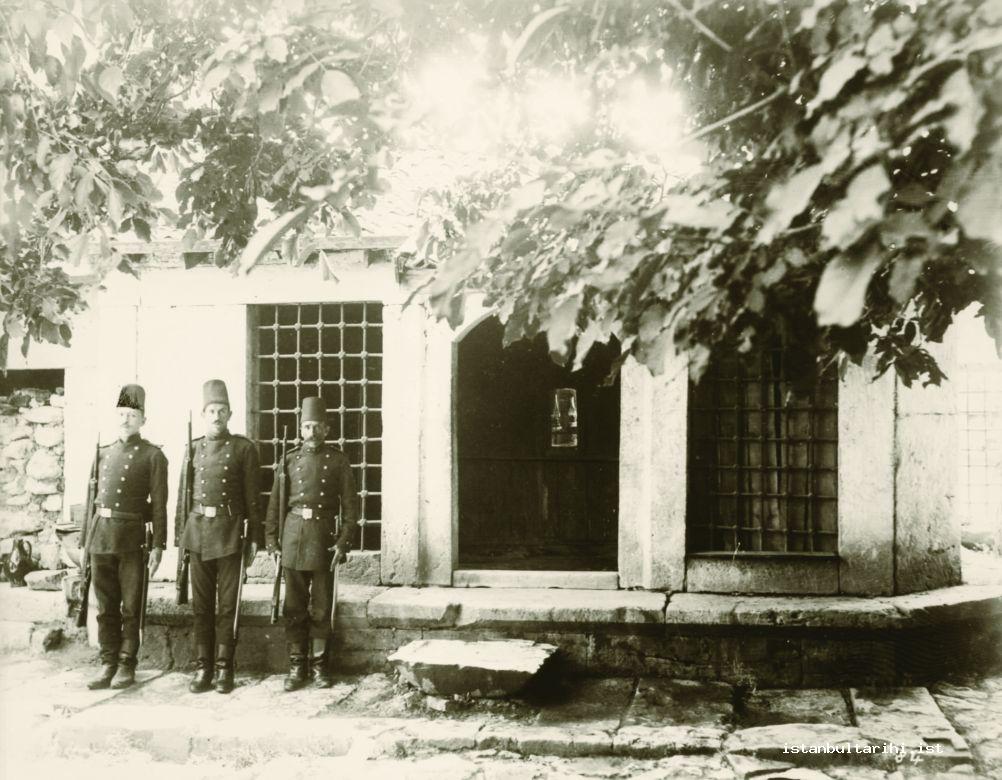

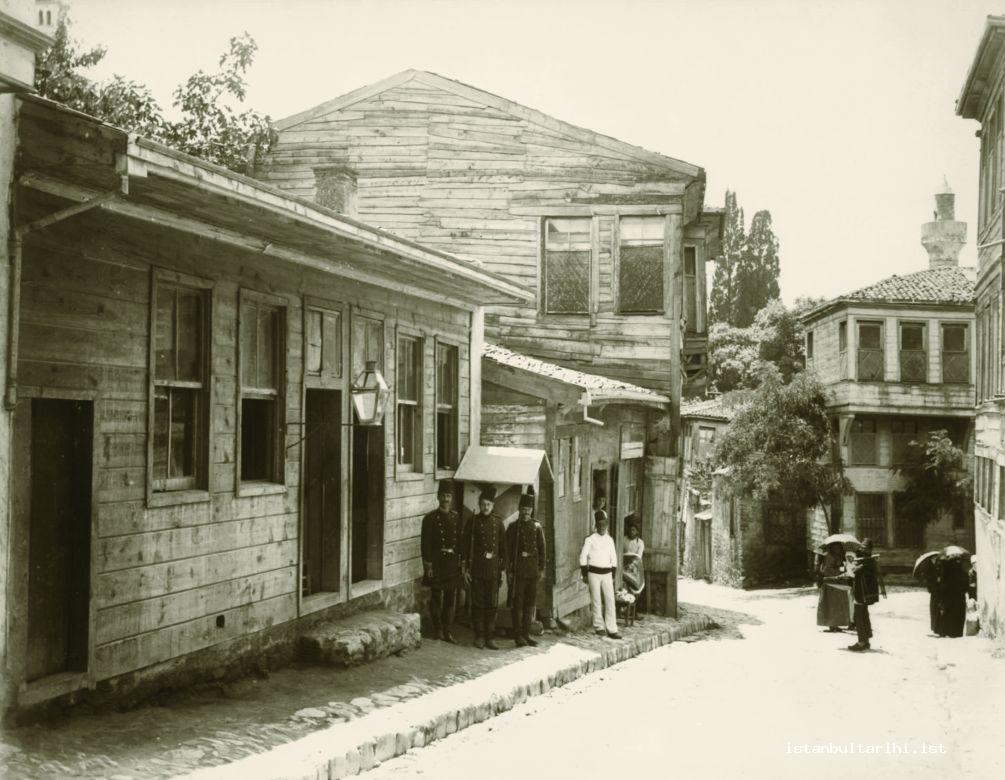

The primary institutions and officials that were responsible for public order and security of Istanbul until Tanzimat Era were the Janissaries and Janissary Agha. Thus, one of the significant changes that happened before Tanzimat was undoubtedly the abolition of the Janissaries by Mahmud II (17 June 1826) and the establishment of a new military organization called “Asâkir-i Mansûre-i Muhammediye” (The Victorious Soldiers of Muhammad). The management of this new army was appointed to a commander called serasker.1 Serasker had the title and authority of senior chief of police of Istanbul. According to this new regulation, Asâkir-i Mansûre-i Muhammediye was responsible for the public order and security of Istanbul side of the capital and Asâkir-i Hassa was responsible for Üsküdar territory. Marines, Asâkir-i Muntazama-i Bahriye (Mariners), were appointed for Kasımpaşa and Eyüp side as in the past. The public order of Galata, Beyoğlu and their surroundings was appointed to the Artillerymen corps as in the past.2 On the other hand, the first police station buildings were constructed during Mahmud II’s reign. These police stations which were previously built from wood in the territories far from barracks and from stone and brick in the territories where the population was dense as of 1831. The first police stations to be built were Bahçekapı, Hatapkapı and Şehzadebaşı police stations. Also, Bostan İskelesi Police Station, Aksaray Police Station, Tevfikiye/Arnavutköy Police Station, Eyüp Otakçılar Police Station (1835), Fatih Police Station (1838) in Eyüp, Şemsi Paşa/Adliye ve Paşalimanı Police Stations in Üsküdar were among the first stone and brick police station buildings in Istanbul. While the buildings that were suitable such as Baba Cafer Dungeon in Yedikule Fortress Zindankapı were converted to police station buildings, new buildings were constructed depending on the needs. The size of police stations and the number of the police who would be appointed to these places depended on the population of the district, number of the buildings and the number of strangers who resided there. The construction of police station buildings started by Mahmud II continued in Tanzimat Era as well.3

One of the arrangements made to solve the public order and security problems that appeared after the abolition of the Janissary was the establishment of İhtisab4 Ministry through a regulation enacted in August-September 1826. İhtisab agha had the duty of provision of public order and subsistence for the public as well as auditing the artisans. According to the regulation, the official for public order could punish an artisan by foot whipping as a warning for other artisans as he was checking the market place; also, he could use his authority to imprison or exile somebody. This ministry was abolished with a new regulation in May 1851 and its duties were given over to Zabtiye5 Marshal. Es‘âr Meclisi6 was set up within Zabtiye Marshal three months later in order to determine the prices of items such as grains, wood, coal etc., negotiate about the operations to be carried out against people who sold the goods over the determined price and who showed their measurements or scales partially and to take the necessary precautions for these problems (13 August 1851). There was a fundamental change in Zabtiye Marshal soon. Accordingly, finance and collection transactions were taken from zabtiyes as the duties of the municipal police increased and they were given over to the Ministry of Finance. Also the assembly was transferred to the Ministry of Commerce as the issues it handled were considered rather related to commerce. Thus, zabtiyes were left with disciplinary work such as security, interrogation etc. İhtisab Ministry was reestablished nearly 5 months after this (4 April 1852) and although Es‘âr Meclisi was given to it, it was dispersed a few months later. İhtisab Ministry was abolished on 25 July 1855 and its duties were given over to the newly established Şehremaneti (Municipality).7

Another important duty assigned to İhtisab Ministry in order to provide public order and security was to prevent idle and errant people from coming from the suburbs to settle in Istanbul. Boaters and porters on the piers, bath attendants in baths and apprentices working for artisans were registered and kept under surveillance in order to ensure this. Also, people without a transit permit, which was necessary in domestic travels, had to be prevented from entering Istanbul. People who had the transit permit and came to Istanbul to work were accommodated in some inns under the control of the ministry until they found a job in order to prevent them from being idle. Furthermore, keeping the records of bath attendants, porters, boaters, bargemen, plasterers, greengrocers, gardeners, drivers, maidens and peasants; head counting them twice a month and preventing them from carrying a gun, finding suspects by controlling bed-sitting rooms, coffeehouses, inns, hotels and slave markets and preventing free people from being sold were considered as the duties of the ministry.8

Zabtiye organization was given more importance in Tanzimat era. There were efforts towards gathering the units of public order and security under one roof. Various manuals and regulations were prepared in order to make these efforts more regular and productive. First legislation in this period were the regulation on 21 March 1845 and Müzekkere-i Umumiye (General Warrant) on 31 March 1845. A copy of this warrant was sent to all embassies in Istanbul and it was stated in this warrant that a new zabtiye practice called “police” started to be implemented; they were given to the command of Tophane-i Amire Marshall Mehmed Ali Paşa; also, an “assembly” was set up to manage this organization.9

The duties of this new zabtiye organization called police and the assembly were explained in the first Police Regulation that was comprised of 17 articles. Accordingly, the primary duty of the police was to watch the trips of foreigners and check their transit permits or passports. As a matter of fact, the new police organization was given to the command of Tophane Marshall that was responsible for the constabulary of this area as foreigners generally came to Istanbul on a ferry and went up to Galata and Tophane. The presence of embassies and foreigner tradesmen in this area and the density of barrooms and brothels undoubtedly played an important role in this decision. In the regulation, matters such as giving license to hunters who would use firearms, providing the protection of state institutions and neighborhoods open to public, preventing people from disturbing people with mendicancy, although they were able to work, helping the poor, unemployed, sick and people, who were discharged from the prison, return to their hometowns, auditing places like inns, restaurants, hotels and bed-sitting rooms, inspecting gambling houses where malevolent people gathered and preventing such places from increasing in numbers, taking precautions against strike action by workers and unrest among them, checking and collecting if necessary the texts and books that would spoil the public morals, taking necessary safety precautions for audience in theatre and other entertainment neighborhoods, regulating the places called “stock market” where merchants work, giving permission to people who wanted to have brokerage and preventing them from working without a license, appointing a chemist, doctor or surgeon in order to determine if a person was sick and why he got sick if necessary, or dead person died due to natural causes, if there was a claim, were considered as the duties of the police.10

It is understood that the aforementioned assembly was assigned to both provide the public order and make the necessary decisions for this issue. Furthermore, assembly was assigned duties that were not stated in the regulation but could clearly be seen in practice such as carrying out the necessary investigation about suspicious people, judging the crimes up to a certain extent and calling the witnesses to the office if necessary. However, the assembly did not have the authority of punishment in its tasks that it was responsible for. Thus, the trial records prepared by the assembly would be transferred to Tophane-i Amire Marshal first and then to Meclis-i Vâlâ (Supreme Court) for verdict and penalty. The assembly started working by employing 46 police officers in the region in May 1845 and its subordination to Tophane-i Amire Marshal did not last long. When the responsibility of public order and security of Galata-Beyoğlu area was assigned to the captain pasha in August 1847, the assembly was given to this office.

On the other hand, although it was stated that a law-enforcement organization called “police” was set up, the old method was resumed substantially in practice when the fact that the assembly was assigned to summon and employ the regular army soldiers located in police stations was considered. As a matter of fact, efforts towards the establishment of zabtiye regiments in Istanbul in a different way from the rural areas started at the beginning of 1847.11 Dersaadet12 felt the need to rearrange the security structure of Beşiktas and Üsküdar upon the reports and complaints of primarily Lord Stratford Canning and English merchants, and other foreign ambassadors and merchants regarding the increase of crimes such as theft and murder in 1850. In the first place it was decided to establish seven troops of zabtiye soldiers and assigning the security work of Galata and Beyoğlu area to Zabtiye Marshal (24 April 1850). It was suggested that the police and bum-bailiffs in that area did not carry out their duties adequately and they should be replaced by 5 troops of zabtiye soldiers as the first step in the report presented by the marshal to the grand vizierate on 8 May 1850 upon the demand for a detailed report on the new system that would be practiced in the area. It was also stated that the police and bum-bailiffs could be included in these zabtiye troops on the condition that they provided a guarantor. Furthermore, it was stressed that an officer should be appointed to Beyoğlu area and a director should be assigned to Galata area in order to command the zabtiye troops. Information about which stations the zabtiye troops, whose establishment was suggested, would be located and what their duties would be was included in the report. Accordingly, the centers of the two troops to be located in Beyoğlu would be Tatavla and Macar locations. The center of the troop in Galata would be Yağkapanı, and the center of the troop in Kasımpasa would be a location in the vicinity. Cavalrymen would be placed in Kağıthane and Alibeykoy. The issues stated in the report were accepted and put into action. The personnel in the police assembly were transferred to Bâb-ı Zabtiye (Gate of Zabtiye) after some time as suggested in the report (3 July 1850). However, security forces that were called “police” within the body of Zabtiye Marshal and that operated since 1845 subsisted as can be understood from some documents although the assembly was abolished.13

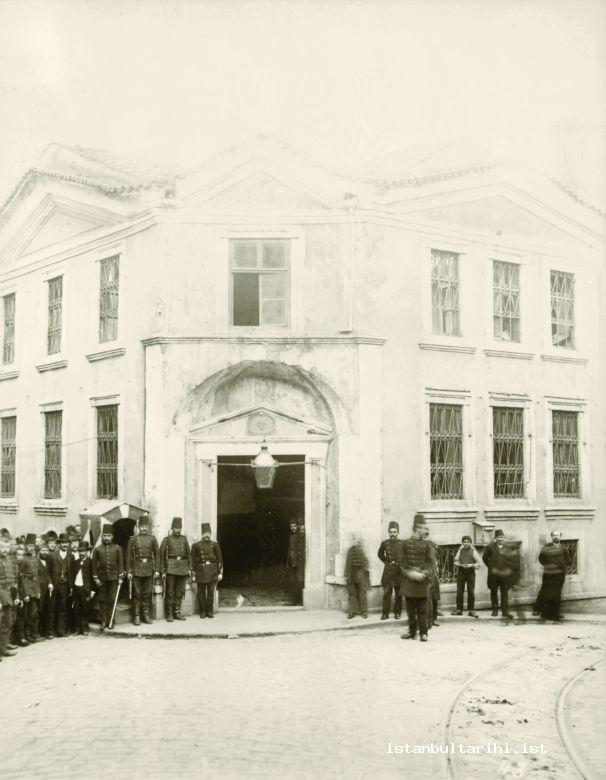

Zabtiye Marshal which has been mentioned above and which formed one of the turning points of Ottoman zabtiye organization was established with an official notice on 15 February 1846. The first person to be assigned to the directorate that started operating in Ticaret Konağı (Trade house) which was in the vicinity of Bahçekapı was the old governor of Niş, Çerkez Hafız Paşa.14 Zabtiye Marshal was established because the constabulary responsibilities of Seraskers caused disruptions in the main duty of soldiers. Although the public order responsibility belonged to the Zabtiye Marshal as of 1846, the marshal was given to and separated from the Seraskerat a few times in the following term. However, it can be said that the constabulary work that was managed by various units until Tanzimat era was gathered in one hand.

One of the important regulations done to ensure the public order and security was the formation of a new zabıta institution called “Memurîn-i Teftişiye” (Inspection Officers). It was stated that four classes of inspection officers were created and their ages should be between 25 and 45 in a document titled “Umûr-ı Zabıta-i Teftişiye Memurlarının Sûret-i Teşkili” (The Organization of Inspection Officers of Zabıta Issues) under the date of 13 April 1865. Also, their salaries, dress codes and duties were mentioned.15 It was stated that the four classes of officers were a different unit than zabtiyes and they would do only police work in a regulation dated 26 July 1867 and also their duties were determined again. These duties included investigating the issues the government was supposed to know, intervening with all municipal police events that they witnessed and giving the necessary warnings and reporting if they fail to intervene. Also, they were responsible for investigating the manners and behaviors of people who visited the country, people who left the country and the passengers inside, checking the passports and transit permissions, informing the government about the people with a fake passport or without a passport. They also made sure that items and provisions were sold for the determined price; inadequate measurement and scales were not used; unbaked and rotten bread was not made; sick and weak animals were not slaughtered; unripe and rotten fruit was not sold and the streets were kept clean. Inspection officers would keep monthly crime statistics regarding the territories they were assigned to and submit them to Zabtiye Marshal.16

It is understood from the analysis of this regulation that they were trying to establish separate law-enforcement forces from zabtiye soldiers in order to replace the police organization that did not become widespread for some reason since its formation in 1845 and that the inspection officers were assigned to particularly intelligence then judiciary, administrative and political constabulary. Also, municipal police works were considered as the main duties of these officers. The police organization founded in 1845 as mentioned above was entrusted similar tasks as well. However, the attempt to set up zabıta forces that would only do the police work did not last long and their tasks were given over to zaptiye soldiers. As a matter of fact, suggesting the reestablishment of inspection offices in a document, dated 10 October 1871, indicates that they were abolished in the same year.17

A new arrangement was applied in the law-enforcement forces of the capital with a new regulation regarding Dersaadet ve Mülhakatı İdare-i Zabıta ve Mülkiye ve Mehâkimi Nizamiyesi (Legal Regulation of Zabıta Management and Administration and Judges of Istanbul and Nearby Cities) on 22 February 1870. Accordingly, the civilian constabulary duties in the capital and its towns in the vicinity were assigned to Zabtiye Marshal. Four assemblies and one agency were founded for this reason. “Meclis-i İdare” (Administrative Council) was responsible for civilian and financial issues. “Meclis-i Fırka-i Zabtiye” (The Division of Zabtiye) was responsible for the selection and administration of zabtiye officers and soldiers. “Teftiş Dairesi” (Agency of Inspection) was responsible for analyzing the documents sent from the directorate through the inspection officers in attendance, taking necessary precautions for putting out fires, finding people sought by the government and performing the operations of people sent to their hometowns or exiled. “Hapishane Dairesi” (Agency of Prison) was assigned to the management of prisons.18 On the other hand, four mutasarrıflıkk19 offices, eight district governorship and five directorates were formed with this regulation. These were Dersaadet, Beyoğlu, Üsküdar, Çekmece mutasarrıflık offices, Galata, Adalar, Kartal, Fatih, Eyüp, Yeniköy, Beykoz, Çatalca district governorships and Küçükçekmece, Suyolu villages, Terkos, Gebze and Şile directorates. This administrative structure, which lasted nearly 10 years, also indicated the zabıta areas. Istanbul was comprised of nine zabıta agencies, Merkez, Fatih, Eyüp, Adalar, Galata, Beyoğlu, Yeniköy, Üsküdar and Beykoz, in the term of Zabtiye Marshal as stated in another source. These agencies were divided into departments and departments were divided into stations (police stations). The departments of these agencies and the number of stations were as follows: the departments in Merkez Zabıta Agency were Topkapı and Kadırga and they were each divided into 11 stations. From the departments in Fatih Zabıta Directorate; Samatya had 13, Salmatomruk 11, Hasanpaşa 11 and old Ali Paşa had 9 stations. Eyüp Zabıta Directorate had only one department which had 12 stations. Adalar did not have any departments but 3 stations. Tophane, which was the only department of Galata Zabıta Directorate, had 15 stations. From the departments in Beyoğlu Zabıta Directorate, Beşiktaş had 6 stations, Ortaköy 2, Arnavutköy 6, Macar 5, Dolapdere 8, Kasımpaşa 8, and Hasköy had 8 stations. From the departments in Yeniköy, Yeniköy had 7 stations, and Büyükdere had 10 stations. From the departments in Üsküdar; Nuh had 9 stations, Çengelköy 9, and Kanlıca had 8 stations. Beykoz did not have any departments but it had 2 stations, İskelebaşı and Kavak. Also, Merkez Zabıta Agency had 1 cavalryman troop at its command. There were 2 cavalryman troops in Fatih, 4 in Eyüp, 1 in Beyoğlu, 2 in Yeniköy, 6 in Üsküdar and 1 in Beykoz Zabıta Agency.20

Another important regulation that could be considered a turning point in zabtiye organization of the Ottoman Empire was the abolition of Zabtiye Marshal and establishment of Ministry of Zabtiye instead on 4 December 1879. The ministry which was considered responsible for the security of Istanbul and subordinate areas at the beginning was later assigned with the administration of the police organization of the whole country. The administration of zabtiye soldiers belonged to Seraskerat. Zabtiye Directorate was replaced by Gendarmerie Agency and Ministry of Zabtiye leaving no possibility of being founded again. After the ministry was founded, efforts towards modernizing the police organization and expanding the police staff numbers started.21 As a result, zabtiye soldiers who were responsible for ensuring the public order and security in Istanbul in 1881 were abolished and replaced by the police organization and the duties of zabtiyes were transferred to the police. Only one gendarmerie troop called “Dersaadet Gendarmerie Troop” which was comprised of only 5 battalions was left in Istanbul. Mutasarrıflık in Zaptiye Marshal’s term was replaced by the “police directorate.” By this way, Istanbul police organization was divided into four agencies, Istanbul, Beyoğlu and Üsküdar Police Directorates and Beşiktaş Police Office and these agencies were divided into stations under the administration of a superintendent. The number of police departments of Istanbul Police Directorate then was 5 and these were Istanbul center, Fatih, Fener, Eyüp and Samatya. The departments of Üsküdar Police Directorate were Üsküdar center, Kadıköy and İskele. The departments of Beyoğlu Police Directorate were Beyoğlu center, Galata, Hasköy, Beşiktaş and Taksim. 22 Zabıta councils that were under the management of mutasarrıflıks before were turned into police councils by decreasing the number of the members.23

The directorates outside of Istanbul Police Directorate were converted back into mutasarrıflık, sort of adopting back the old method after 1886. By this way, the police administration of Istanbul was divided into 3 agencies, Beyoğlu and Üsküdar mutasarrıflıks and Istanbul Police Directorate. These were divided into police departments and stations as in the past. Each department was considered as a police division and given to the command of a superintendent. Second and third class commissioners and police sergeants were at their command.24 39 divisions and one cavalryman division in Istanbul, Beyoğlu and Üsküdar were established in 1902.25 Furthermore, there was a gendarmerie troop that was under the same ministry and responsible for the public order of Istanbul.26 A civilian police organization was formed on 23 May 1899 from the people who could speak foreign languages and who were appointed to following ramblers, suspects and people without a passport. They were also responsible for investigating the source and the means of harmful publications and auditing nearly 100 printing houses in Istanbul.27 Towards the end of the term of Zabtiye Ministry, there was one police organization under the command of a chief of police or a superintendent in almost every city.

Apart from the police, gendarmerie and zabtiye that provided the security of Istanbul, there was an organization with a small personnel cadre called “bugs” that existed from the 18th century till the beginning of the 20th century. The civilian officers called “stray” in this organization that acted as secret zabıta and that was under the administration of a chief called “head of the bugs” were responsible for investigating the incidences with an unknown perpetrator. These people who were chosen from old criminals could easily unveil who the perpetrators were since they knew well the details of crimes such as theft, murder, pickpocketing and robbery and where the criminals would hide. They would generally deliver the criminals to the respective units but they would sometimes punish the criminals themselves.

One of the security forces that directly acted as zabıta or helped zabıta was warders. They existed in the period before Tanzimat and their salaries were given by the inhabitants of the neighborhood. Warders knew the inhabitants of the neighborhood very well so they watched strangers who came to the neighborhood from somewhere else closely, kept an eye on the houses of people who went out of town and warned people in case of a fire at night. Warders, who regulated the relationship between the public and the people in power such as the headmen of neighborhoods and imams, helped the police in rulers’ observation of the public in order to ensure the public order as well as protecting the property and lives of people. As a matter of fact, the intelligence task appointed to the warders was put into writing through the second article of a regulation dated 2 December 1896.28 Also there were market warders who were responsible for protecting the artisans against theft.

Right after the proclamation of Second Constitutional period, efforts to regulate the market and neighborhood warders started. “Neighborhood guards” were deployed instead of neighborhood warders in Istanbul in 1909. It was decided that these sergeants whose appointment and employment depended on zabıta and administration depended on the municipality should have uniforms, and they should carry a whistle, inspection notebook and a weapon (revolver) instead of the sticks they used to carry. They were also given the duties of following suspects, investigating where people who stayed in inns and hotels came from, and intervening in case of a crime and arresting the criminal. On the other hand, neighborhood warders continued to exist although irregularly. On 14 May, it was finally decided in a temporary law that the salaries of the market and neighborhood warders should be regulated and that they should get the approval of Istanbul police directorate before they started working. However, Istanbul governor office stated that the warders came under the influence of community council and the head of the neighborhood and they could not carry out their duties objectively since their salaries were paid by the public as in the past.29 Also, as the wage paid by the public decreased, the warders started working at other jobs which made it difficult for them to stay awake all night while working. This was another reason why the warders could not be as efficient as desired.

Social and economical problems caused by the political developments in regulations regarding the security are inevitable. As a matter of fact, separatist national movements that appeared in the Ottoman Empire at the beginning of the 19th century started to threaten the domestic security with the support they received from Russia, England and France. Thus, observing the foreigners and missioners who came to the Ottoman land and travelled here for various reasons gained importance. In subsequent terms, the social mobility created by the Muslims who had to emigrate from the lands that were lost in particularly Crimea and Balkans made it necessary to observe and get information about which groups settled where and why individuals travelled from one place to the other. Therefore, the practice of carrying a passport for people travelling to and from abroad and transit permission for people who travelled within the country became common. The officials the state relied on in order to strengthen its authority by bringing citizens under its control were the headmen of the neighborhoods, customs and harbor officers and security forces such as the police and gendarmerie. The headmen of the neighborhoods who were the guarantors of the inhabitants of the neighborhood and whose main duty was to provide security would investigate the situation of strangers who came to their neighborhood and check if they had the transit permission. They would inform respective officials about suitable people that they could stay after asking them questions such as why they came and how long they would stay if they had a permission document; otherwise, they would inform them that suspicious people or people without necessary documentation should be sent to where they came from. If necessary, customs and harbor officers helped by the police as well would try to ensure the public order by preventing the criminals, harmful publications, weapons and explosive substances from going into the country.

Efforts were towards preventing the migration of unemployed and stray people, in other words potential criminals, to Istanbul from suburbs through the transit permission. This practice was valid for both Muslims and non-Muslims. People who wanted to come for trade were not prevented. Thus, both ensuring the public order in Istanbul and preventing people from being poor and miserable were aimed, as well as watching the citizens closely and recording them. However, the citizens were trying to convince the officials with reasons such as doing business and needing a change of air in order to avoid the supervision. The government was taking new precautions in the meanwhile. This practice was replaced by the travel document after Constitutional Monarchy and identity documents were given to madrasa students, artisans, laborers and porters so that the supervision over these classes, that sometimes caused incidences, was ensured.

Security gained even more importance as a result of the increasing competition among European states over Ottoman land in Abdulhamid II’s reign. The Ottoman Government, on the other hand, was trying to prevent internal disorder through protection of the property, lives and honor of all subjects, either Muslim or non-Muslim, and announcements about ensuring peace and welfare of each individual. Also, it wanted everybody to be occupied with their own jobs and to stay away from illegal and forbidden situations.30 Also, the government was taking new precautions against situations that spoiled the public order. Armenian committees such as Hınçak and Taşnak caused many incidences that spoiled the public order and security particularly as of early 1890s. They were hoping that the European states would intervene with Ottoman State and their road to freedom would open this way. The members of Hınçak and Taşnak, who thought the protests in the suburbs were not influential enough, moved their protests to Istanbul later. The main protests were the raid of Kumkapı Armenian Patriarchate and Church (28 July 1890), marching towards Bâbıâli with a group of 4000-5000 (30 September 1895), and the invasion of Ottoman Bank where the number of foreigner national workers was high (26 August 1896). People from the committee could not get the attention they desired in the European public opinion due to the use of proportional force and appropriate attitude by the security forces and they attempted to assassinate Sultan Abdulhamid II with a time bomb (21 July 1905). The sultan had the Friday prayer in Yıldız Mosque as always and he avoided the assassination because he took some time talking to Şeyhülislam Cemaleddin Efendi before he got into his car but many people died or were wounded in the crowd. The assassination plan was understood to have been made in Sofia according to the investigation. All these incidences forced Abdulhamid II to watch primarily Bulgarian and Armenian committees and Young Turks that defended freedoms and constitutional government and many other issues; therefore, he also established a broad civilian intelligence organization apart from the modern police organization. The presence of this intelligence organization became one of the main criticism subjects of the subsequent administration in terms of individual rights and freedoms.

After the proclamation of the Second Constitutional period (23 July 1908), the Committee of Union and Progress could not manage power completely; there was a free environment caused by this change and many old administrators and police were discharged claiming that they were spies. All of these caused harm to the public order. Factors such as the publication of hundreds of newspapers and magazines and establishment of many associations all of a sudden increased disorder because the censorship and political amnesty that was granted to demonstrations, meetings, worker strikers and political criminals at the beginning included all criminals later and it was abolished soon. This situation undoubtedly started threatening the property and lives of people and disturbing the public. As a matter of fact, the crime statistics showed there was an increase in some crimes. News regarding failure of the police to do their job and the increase of some crimes escalated in the press. When the Unionists who tried to settle things down through circulars in this chaos at the beginning failed to do so, they started making efforts towards having the control over the police in order to strengthen their positions. For this reason, they organized the reaction against Beyoğlu Mutasarrıf Hamdi Bey who was appointed to Zabtiye Ministry by Abdulhamid II after the declaration of Constitutional Monarchy. Hamdi Bey was dismissed upon reactions. Edirne Governor Ziver Bey who replaced him had to resign after five or six days so first Ferik (lieutenant general) Sami Pasha then Ferik Ali Pasha (15 April 1909) were appointed to the post. As can be understood from these events, there was instability in the administration of Zabtiye Ministry.

Both the instability and certain practices of Unionists caused some backlash after a while. As a matter of fact, the emergence of opposition such as Ottoman Liberal Party and Union of Muhammad Party (İttihad-ı Muhammedi Fırkası) founded on 14 September 1908 and the assassination of some opponents by unknown assailants escalated the reaction against Unionists and a countercoup movement broke out on 31 March/13 April 1909. The Action (Hareket) Army from Thessaloniki came to Istanbul and quashed the riot. Subsequently, Abdulhamid II was dethroned on the grounds that he was involved in the riot. This event, known as 31 March incident, gave the Unionists the chance to abolish Zabtiye Ministry and form a new police organization under their own supervision.

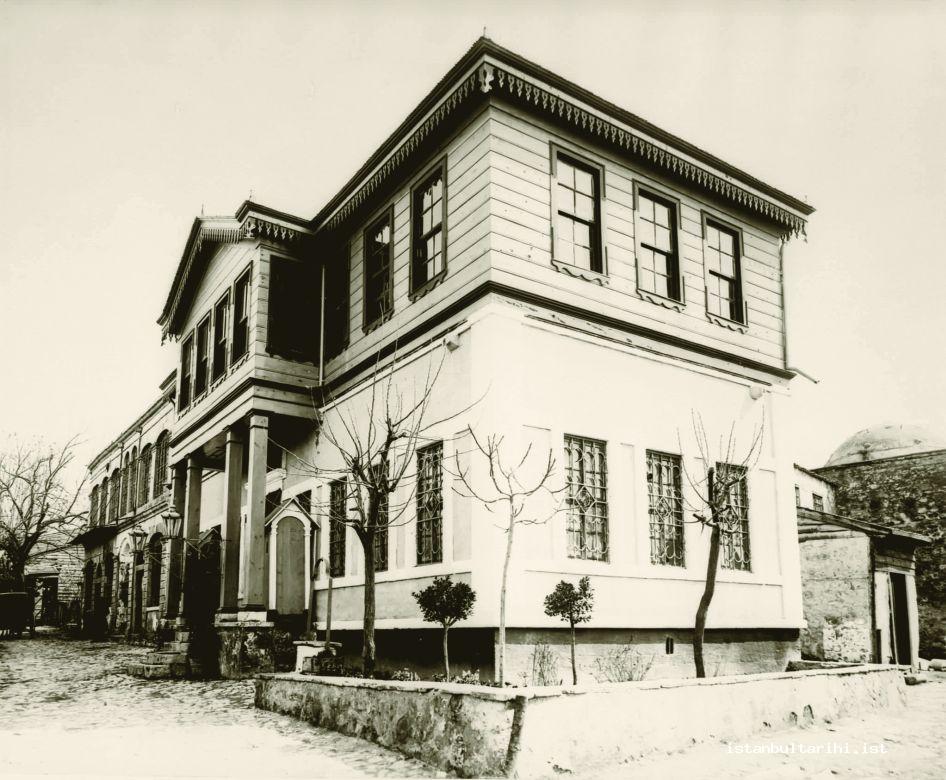

The first regulation in this sense was to establish “Inspector General of Gendarmerie and the Police” and appoint one of the officers of Action Army, Colonel Galip Bey to this post.31 This also caused the emergence of a military influence in the new structure. After a while, Zabtiye Ministry was abolished through Law Regarding the Organization of City of Istanbul and Security General Directorate introduced on 4 August 1909 and “Security General Directorate” was founded directly under the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Issues regarding zabıta and public order in Istanbul were given to Istanbul Police Directorate under the governor. It was stated that the Security General Directorate would function in compliance with the current regulation until a new Police Regulation was prepared.32 The old aide of grand vizierate, Cemal Efendi’s mansion behind Kağıtçılar in Beyazıt was rented and turned into the directorate building.33 Inspector General of Gendarmerie and the Police Galib Bey was appointed as the director on 12 August 1909.34

On the other hand, although Beyoğlu and Üsküdar mutasarrıflık were converted to the police directorates after the proclamation of the Second Constitutional period, they were turned into mutasarrıflık again when the benefit expected from this change in terms of public order was not gained.35 However, these mutasarrıflık were turned into Beyoğlu and Üsküdar Police Directorates once more during the organization of Security General Directorate and the heads of the police assemblies that were abolished were assigned to these directorates.36 Also, Marine Department Office was set up. These directorates were given to the management of an officer so that the work could be carried out faster and more regularly. These 31 departments were divided into stations and stations were divided into posts.37

Both Security General Directorate and Istanbul Police Directorate under the governor’s office were held responsible for the public order in Law regarding the Organization of City of Istanbul and Security General Directorate and this caused authority confusion between these two institutions and some complaints so it was decided that the general security of Istanbul would be taken from the governor and given directly to Security General Directorate.38 However, these arguments continued for a while and a general directorate (Istanbul Police General Directorate) directly under the Ministry of Internal Affairs like Security General Directorate was established.

As a result of the draft law prepared upon the request of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and negotiations in the First Parliament, two articles in Law Regarding the Organization of City of Istanbul and Security General Directorate were amended (4 June 1911).39 According to the new regulation, Security General Directorate would be a branch of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and would not be responsible for the public order of Istanbul. The public order and security of Istanbul was assigned to Istanbul Police General Directorate that was established directly under the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Üsküdar and Beyoğlu Police directorates would be a part of the general directorate.40 Prishtine Mutasarrıf Mazhar Bey was appointed as the Police General Director.41 Later, the gendarmerie in Istanbul became a part of Istanbul Police General Directorate regarding the issues of public order of Istanbul.42

There were some significant changes in the police organization with the Police Regulation, dated 15 May 1913, that was put into effect a few months after Bâbıâli raid on 23 January 1913 when the Unionists took over the administration. The election of officers working under Istanbul Police General Directorate was given back to Security General Directorate in this period. Thus, Istanbul Police General Directorate partially lost its full independence that it possessed at its establishment because proceedings related to personnel affairs of the police were given to Security General Directorate although the management of the security issues of Istanbul was the responsibility of Istanbul Police General Directorate. Istanbul Police General Directorate continued to carry out police service of Istanbul until it was abolished on 24 February 1923 and replaced by Istanbul Police Directorate.

Both the Security General Directorate and Istanbul Police General Directorate tried to ensure the public order of Istanbul through opening new branches and creating new personnel vacancies as needed. The security forces tried to prevent the negative results of strikes, boycotts, and trafficking caused by the war from harming the public in this period. They particularly aimed, through the police, to protect the youth from harmful habits such as gambling, drugs and prostitution that would undermine their morals and push them to criminal activities. Also, the police collected the weapons in order to prevent the increase in killing and physical injury incidents caused by the increasing armament in the public. On the other hand, it can be understood that public order and security were given extra importance in ferry ports, train stations, Grand Bazaar and Galata Bridge as well as places such as ferries, trains, theatres and cinemas where mendicancy, theft, pickpocketing, insulting, fighting and physical injuries would be experienced more often due to the density of people in these areas. As a matter of fact, the practice of having the police in these places started for the peace and security of life and property of the public. More mobile patrols were appointed and security precautions were increased in the holy month of Ramadan, sultan’s visit to the Holy Mantle, Easter, Hıdırellez, 10th day of the month Muharrem, days of fairs and picnic season in the beginning of spring. Furthermore, Istanbul seaside was guarded at night through rowing boats primarily in Bosphorus and Golden Horn although it was sometimes disrupted.

All these aforementioned efforts aimed to monitor both criminals and suspects and to ensure that the public lived in a peaceful and safe environment. They were generally carried out indiscriminately in terms of ethnicity and religion as long as there was not an opponent situation or perception against the administration. However, the activities of observing and recording by the state increased in accordance with unrests that emerged in parallel to the political developments. On the other hand, the increase in transportation and communication opportunities, the development of ethnic awareness and social, economical and cultural changes were directly related to the public order and security; therefore, there was a constant need for new regulations. Moreover, there was difficulty in gaining the expected favor as each regulation brought new problems and uncertainties with it. Despite this situation, success was achieved in some issues. It should not be forgotten that the police organization of the Committee of Union and Progress term constituted the foundation for the organization and practices of Republican period.

FOOTNOTES

1 Serasker or Seraskier is a title formerly used in the Ottoman Empire for a Vizier who commanded the army, and later for the National Minister of Defence.

2 Halim Alyot, Türkiye’de Zabıta: Tarihi Gelişimi ve Bugünkü Durum, Ankara : İçişleri Bakanlığı, 1947, p. 70.

3 Necla Arslan, “II. Mahmud Döneminde Modern Bir Polis Teşkilatının Kuruluş Girişimleri, İlk Karakol Binaları”, İstanbul, 1997, no. 23, pp. 37-41. See BOA, C.ZB, no. 3188 (21 L 1257/6 Aralık 1841) fort he names and repair expenses of some present police stations in Üsküdar territory of Istanbul in 1840.

4 Ottoman constabulary-office for public order

5 Military police organization that was responsible to ensure the public security in Ottoman Empire

6 Assembly to determine officially fixed prices

7 Ziya Kazıcı, “Hisbe”, DİA, XVIII, 143-145; Ali Akyıldız, Tanzimat Dönemi Osmanlı Merkez Teşkilâtında Reform (1836-1856), Istanbul: Eren Yayıncılık, 1993, pp. 287-289.

8 Osman Nuri Ergin, Mecelle-i Umûr-ı Belediyye, İstanbul 1995, vol. 1, pp. 317-347.

9 “Sefaretlere Yazılan Müzekkere-i Umûmiyye Sureti”, see. Ergin, Mecelle-i Umûr-ı Belediyye, vol. 2, pp. 878-880.

10 Ergin, Mecelle-i Umûr-ı Belediyye, vol. 2, pp. 875-878.

11 BOA, İ.MMS, no. 134 (1 S 1263/18 Ocak 1847); BOA, C.ZB, no. 2772 (5 L 1264/4 Eylül 1848); no. 3642 (21 Za 1265/9 Ekim 1849).

12 One of the names of Istanbul

13 Ali Sönmez, “Polis Meclisi’nin Kuruluşu ve Kaldırılışı (1845-1850)”, TAD, 2005, vol. 24, no. 37, pp. 264-269.

14 Takvîm-i Vekâyi‘, 1262, no. 297; Lutfî, Târih, Istanbul: Sabah Matbaası, 1328, vol. 8, p. 88.

15 BOA, YEE, 36/7 (17 Za 1281).

16 23 Ra 1284/26 Temmuz 1867 tarihli “Memurîn-i Teftişiyyenin Sûret-i İntihab ve Vaz‘ ve Hareketleri Hakkında Tarifatı Mutazammın Talimat”, Düstur, Birinci tertip, Istanbul: Başvekalet Neşriyat ve Müdevvenat Dairesi Müdürlüğü, 1289, vol. 2, pp. 748-753.

17 BOA, ZB, 4/20 (26 B 1288).

18 Düstur, Birinci tertip, Istanbul: Başvekalet Neşriyat ve Müdevvenat Dairesi Müdürlüğü, 1289, vol. 1, pp. 688-702; Alyot, Türkiye’de Zabıta, pp. 90-91. See BOA, ZB, 4/20 for the organization, personnel and salaries of Zabtiye Directorate.

19 The name given to the administrators of sanjaks in Ottoman administration structure after Tanzimat

20 Alyot, Türkiye’de Zabıta, pp. 106-108.

21 BOA, Y.PRK.SRN, 1/26 (20 C 1297/29 Mayıs 1880); BOA, A.DVN.MKL, 71/42.

22 Alyot, Türkiye’de Zabıta, p. 183; Hikmet Tongur, Türkiye’de Genel Kolluk, Teşkil ve Görevlerinin Gelişimi, Ankara : Kanaat Matbaası, 1946, pp. 165-166.

23 BOA, ŞD, 1285/21 (24 Za 1299/5 October 1882).

24 Alyot, Türkiye’de Zabıta, pp. 184-185, 194; “18 Nisan 1907/5 RA 1325 Tarihli Polis Nizamnamesi”, Düstur, Birinci tertip, Istanbul: Başvekâlet Devlet Matbaası, 1943, vol. 8, p. 667. There were 8 departments and 62 stations in Istanbul, 6 departments and 49 stations in Beyoglu and 3 departments and 37 stations in Uskudar in 1891 (BOA, ZB, 44/18 (28 September 1307/10 October 1891).

25 BOA, Y.PRK.ZB, 32/51 (2 May 1318/15 May 1902).

26 According to the statement of Zabtiye Minister Şefik Paşa, although 2178 people were registered in Dersaadet Gendarmerie Troop as of 5 April 1900, 120 zabit and 2058 privates, the total number was 1678. There were 300 police stations and 21 agencies in this date (BOA, DH.TMİK.S, 32/4 [23 March 1316]).

27 23 May 1899, BOA, İ.ZB, no. 1 (12 M 1317).

28 “Dersaadet ve Bilâd-ı Selâsede Asayiş Vazifesiyle Mükellef Olan Nizamiye ve Jandarma Asâkir-i Şâhanesiyle Polis Memurlarının Sûret-i Hareketlerine Dair Talimat”, BOA, Y.EE, 6/19 (20 Teşrînisâni 1312).

29 BOA, DH.EUM 6. Şb, 5/18 (31 Kanunuevvel 1331/13 Ocak 1916).

30 BOA, Y.PRK.BŞK, 57/41 (23 August 1898).

31 BOA, DH.MKT, 2902/53 (16 Ağustos 1909/3 Ağustos 1325); BOA, DH.EUM.MH, 2/134 (13 Ekim 1909/30 Eylül 1325).

32 BOA, DH.MUİ, 4-1/39, lef 5; Takvîm-i Vekâyi‘, 1325/1909, no. 338, p. 7.

33 Tanin, 17 Ağustos 1909, no. 344, p. 3; BOA, ML.MKT.d, no. 468, s. 171.

34 BOA, BEO, no. 271301; BOA, DH.MKT, 2898/31 (30 Temmuz 1325/12 Ağustos 1909); Tanin, 13 Ağustos 1909, no. 340, p. 3; Takvîm-i Vekâyi‘, 1325/1909, no. 302, p. 1.

35 BOA, ZB, 326/126 (30 Eylül 1908/17 Eylül 1324).

36 BOA, DH.MKT, 2902/8 (16 Ağustos 1909); 2908/49 (17 Ağustos 1909/4 Ağustos 1325).

37 İstanbul Police Directorate was comprised of Merkez, Ayasofya, Cisr-i Cedid, Kapan-ı Dakik (Unkapanı), Fener, Eyüp, Kumkapı, Aksaray, Fatih, Karagümrük, Şehremini, Samatya, İstasyon, Deniz, Büyükada and Makriköy. Beyoğlu Police Directorate was comprised of Merkez, Galata, Hasköy, Kasımpaşa, Pangaltı, Arnavutköy, Büyükdere, Dolapdere, Beşiktaş and Taksim; Üsküdar Police Directorate was comprised of Paşakapısı, Çinili, Kadıköy, İskele and Haydarpaşa departments (Takvîm-i Vekâyi‘, 1325/1909, no. 344, pp. 5-6).

38 BOA, DH.MUİ, 69-1/71 (23 February 1910/10 February 1325); BOA, MV, 137/86 (8 March 1910/23 Şubat 1325); BOA, BEO, no. 278706 (9 March 1910/24 February 1325).

39 “İstanbul Vilayeti ve Emniyet-i Umûmiyye Müdüriyeti Teşkilatına Mütedâir 17 Receb 1327 tarihli Kanun’un 4. ve 5. Maddelerini Muaddil Kanun”, Düstur, İkinci tertip, Istanbul: Matbaa-i Osmaniye, 1330, vol. 3, pp. 433-434; BOA, DH.İD, 27/21, lef 2, 4 (4 Haziran 1911/22 Mayıs 1327); Takvîm-i Vekâyi‘, 1327/1911, no. 846.

40 Tanin/Senin, 30 May 1911, no. 985-9, p. 2.

41 16 Haziran 1911. BOA, İ.DH, no. 14 (18 C 1329).

42 BOA, MV, 155/23 (6 August 1911/25 July 1327); BOA, DH.İD, 27/21, lef 11, 12, 13.