The Administration of Istanbul from the Tanzimat to the Republic

As the capital and the largest city of the Ottoman state, during the Tanzimat period, Istanbul started to face new undertakings and applications in city administration; these ran parallel to the effects of economic, social, and technological factors. The main characteristic of this change was the transformation from the traditional Ottoman city administration towards a “modern” European municipality model. Modernization through the integration of Istanbul into the new world trade order and the Tanzimat reforms, which were based on Westernization and centralization, constituted the two important axes of this process.

“The modern institution of municipality”, which started to replace the administrative institutions of the classical period, was a new structure that emerged in the 19th century, during the process of change that followed the Industrial Revolution. The rapid urbanization in Great Britain, which was the result of industrialization, led to many problems in a number of areas, such as housing, the environment, transportation, security, health services, etc. Parallel to the characteristics and the size of changes in the local services, the structure of the administration of the cities also underwent changes. In this process, there were attempts to answer the need for public services by introducing new models of organization in areas of special services as well as attempts to improve the former urban institutions. In following days, a process of transition towards a specialized structure of a single local administration that was responsible for local services began. The modern institution of the municipality developed and was legitimized by establishing standard structures of local administration based on specialization instead of structurally or functionally varying models, the development of a legal basis, and the transfer of the responsibilities of the local services to the local administrations. In Great Britain, codes of local administration were introduced in 1835, 1888, and 1894, while in France, the structures of local administrations developed following the 1789 Revolution, with constitutional regulations introduced in 1830 and 1848, and a local administration code in 1884; in Germany, the 1808 Prussian City Regulation marked an important step in the development of the modern municipal institution in Europe.

The effect of industrialization and the migration of the rural population to the cities, although introducing a multifaceted transformation to the city of Istanbul, remained limited when compared to European cities. The primary reason for this was that the Ottoman Empire did not undergo the process of the Industrial Revolution in the same way that Europe did. In this context, it is possible to study the transition in Istanbul’s administration from the structures of the classical period to the modern municipality model in four stages. The first stage was the remarkable expansion in the concept of local services which accompanied the multifaceted and international transformation that Istanbul was undergoing. The second stage was a period in which the functions of the classical structures of the city administration decreased, and thus there was an accompanying increase in the problems experienced in local services. The third stage was the application of modern municipality models to solve these problems. The fourth stage was the expansion of the area of legitimacy for the modern structures of the municipality and their development as principal units of city administration.

The international commercial order in the 19th century was reshaped within the context of an increasing need for raw materials and new markets; this new demand was caused by the rapid economic expansion that took place following the Industrial Revolution. Faced by this need, the new commercial order seriously affected the Ottoman State, a country with a high potential. The signing of trade agreements between the Ottoman State and European states enabled foreign merchants to freely carry out trade in the Ottoman State, thus enhancing the level of integration into the new commercial order. In particular, parallel to increased commercial relations, port cities located within the Eastern Mediterranean basin, such as Istanbul, İzmir, Thessaloniki, Alexandria, and Beirut, witnessed important economic, physical, social and political transformations.1

Bazaars, caravansaries, and market places (kapan), which had been the center of commercial life in Istanbul, experienced a decrease in the volume of economic activities; the district of Galata came to fore as the main commercial center. The organization of new economic relationships began to be undertaken by establishments such as companies, banks, and insurance agencies. The guilds, which had had a significant place in the organization of the city administration, lost their position when the market places departed from their central status in commercial life; in addition workshop-type production started to disappear, giving way to factory manufacturing, and there was a change in public consumption habits. These factors also led to a decrease in the functions of the guilds in governing commercial areas and control of commercial life.2

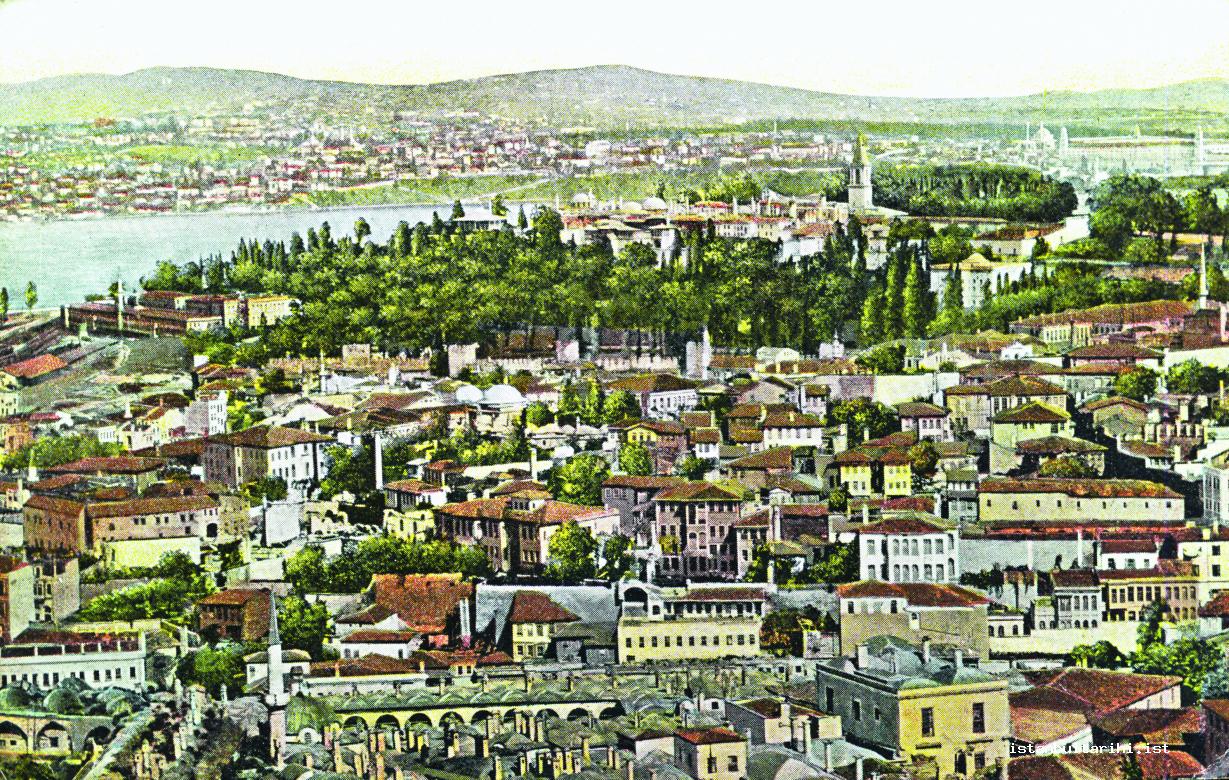

As with many other port cities in the Ottoman State, the economic change experienced by Istanbul led to many accompanying social changes. The cosmopolitan social structure that was fostered by international trade and parallel features in daily life were very different in the Galata-Beyoğlu district than in other parts of Istanbul. Market places and stores, hotels, inns, embassy buildings, entertainment places and houses that had been constructed as a reflection of social and economic changes in the area became the new face of the Galata-Beyoğlu district, an area where Western merchants, middlemen, developers and bankers were concentrated. In addition to the development of new resident areas, such as Şişli, Nişantaşı and Maçka, as well as summer resorts such as the Princes’ Islands, Tarabya and Yeniköy, which had been integrated into the daily life thanks to the ferries run by the Hayriyye Company, developed as the new neighborhoods of residence for the wealthy population. Those who moved to Istanbul from rural areas settled primarily around Eyüp, Hasköy, Kasımpaşa and Üsküdar.3

The classical structure of neighborhoods was under the influence of two important dynamics during the Tanzimat period. The first one was that the population which moved from the rural areas to Istanbul was dense enough to make control of the organizational structure of the neighborhoods difficult. The second one was that the relocation of the wealthy families in regions where families of similar status resided, a result of new economic relationships, created a structure that was different from the classical structure. By damaging the integrity of the relationship between the constituents of the neighborhood organization, these two developments weakened the functions that had been provided by the neighborhood administration. The main problem area was that the imams, the head of the neighborhood administration, were not able to maintain order in the neighborhood. In 1829 attempts were made to restore order by appointing a “first” and “second” neighborhood muhtar (headman) who would take on the administrative and judicial tasks of the imams.4

The structural changes experienced by the society and the state also had an effect on the wakfs, an institution that had a very important role in the execution of local services. As a result of the effects of normative regulations, as well as changes in mentality, attempts “to establish endowments” decreased during this period. With the pressure caused by the weaknesses and corruption in the existing management of the wakfs, the Ministry of Wakfs was established in 1826.5 Despite the establishment of this ministry, a regulation that was in keeping with the perception of a centralized administration, the problems could not be solved.6 In addition to these changes, which reduced the functions of the wakfs, the establishment of institutions that could take their place, such as schools and hospitals, was another factor that affected this process. The wakfs had played an important role in the integration of the stipulations set out in the wakf deeds and the organization of services, however, there was now a decrease in these functions within the context of local services in the city.

Officials such as kadies (judges), muhtasib (policeman who examined weights, etc.), subashi (police superintendent), and mimarbaşı (head architect) represented the state in the administrative organization; these same officials were negatively affected by the administrative reform applications which began in the first quarter of the 19th century, and which increased with the Tanzimat edict. These reforms led to a decline in the functions of some officials, while others were abolished altogether. As a consequence of the abolishment of the Janissary corps in 1826 officials, the introduction of posts such as the subashi, ases (night-watchman), and çöpçü subaşısı (superintendent of the garbage collection) weakened the function of the kadies in controlling the city. The kadies, who lost their authority over the wakfs with the establishment of the Ministry of Wakfs also lost their connection with the grand vizier; judges now fell under the authority of the sheikh-ul-Islam, and were responsible only within limited matters of civil law. The classical period of city administration had consisted of private institutions and state officials, in which the kadies had played a leading role; however, this new situation meant the end of the role of the kadies in the city administration;

Within the efforts to centralize the administration, the office of muhtasib, which was one of the most important offices for inspecting the tradesmen, was reorganized under the Ihtisab Nezareti (Ministry of city officials) in 1826. This new ministry was responsible for collecting the newly issued taxes and already existing ones; however, it was later abolished and its functions were transferred to the Seraskerlik (Ministry of War) and the Ministry of Finance in 1851. Later, the functions related to safety in the city, which had been transferred to the Seraskerlik, were transferred to the Zaptiye Müşirliği (Office of the field marshals,) which was established in 1845. This office also took care of the lighting and sanitation of the city until 1855. Es’ar Meclisi (the board of market prices) was established in order to carry out the tasks related to the Ihtisab.7 In 1852, the Ihtisab Ministry was reestablished in order to carry out inspection of tradesmen and the collection of the taxes. Three years later Ihtisab Ministry was abolished once again, and its responsibilities were transferred to the newly established Şehremaneti (Prefecture).

In 1831 a new institution called the Ebniye-i Hassa Müdürlüğü (Directorate of imperial buildings) was established by uniting mimarbaşılık (the office of head architect) and şehreminlik (the office of the prefect), which had played a very important role in the administration and the development of the city.8This new directorate, which was responsible for the development of the city, carried out a number of services; for example, commissioning Moltke to draw up a map and blueprint of the city, the preparation of the Ebniye Nizamname (building regulations), and constructing roads and pavements. In the following years the Ebniye-i Hassa Müdürlüğü carried out services in a variety of structures under the authority of Meclis-i Umûr-ı Nâfia (commission of beneficial affairs) and the Ministry of Commerce; after the establishment of Şehremaneti (the Prefecture) in the city this directorate was transformed into the Hendesehane (department of engineering), under the control of Şehremaneti.

In Istanbul the concepts of “local service” and “municipal organization” were affected and changed by the developments of the 19th century, undergoing a process of redefinition within the framework of social, economic, and technological developments. The quality, range and size of the services broadened. A need for new organization emerged in parallel to demands for new local services. The municipal officials and the institutions of the classical period, however, remained outside the process of redefining concepts of “local service” and “municipal organization.” When officials like the qadis, muhtasib, subaşı, and mimarbaşı became weakened due to cyclical developments and general administrative regulations, an authority gap appeared in local services in Istanbul. The loss of functions of the waqfs, lonca (guilds) and other neighborhood structures that had had roles in providing local public services led to a decrease in local public services in Istanbul; indeed this reached a level far below what had existed in earlier times. An important gap occurred in local services, for example, the provision of water, transportation, substructure, control of buildings, inspection of tradesmen, lighting, sanitation, etc.

Most of the requests of the local Istanbul population were concerned with reforming the classical institutions of the city to solve the problems of the municipality. On the other hand, those who lived in the neighborhoods of Beyoğlu-Galata or in similar areas, i.e., those who held economic and political power, wanted the European municipal model to be applied to Istanbul. The basis of legality and influence achieved by these social classes within the context of their relationship with Europe became one of the most important factors shaping the new form of administration in Istanbul.

The Tanzimat Era bureaucracy’s approach to the problems of Istanbul, in parallel with the reform approach of the era, was centered round the axis of Westernization, modernization and centralization. Ottoman ambassadors brought the news of the rising modern state in Europe and in their reports discussed the ever-present Napoleonic state, its police organization, postal services, etc. They were puzzled as to how every new service of the state was filling the treasury with more money. The reports of the ambassadors were filled with their admiration for the carefully planned European cities, their wide streets and avenues, and tall buildings.9 In this period, the legal basis of the responses domestic and foreign developments given by statesmen who formed the sector of society which “made the decision to change”, switched from Kanun-i Kadim (the old law) to criteria that originated from Western Europe.

Istanbul constituted a contradiction to European cities in the matter of the local public services. When news about the situation in Istanbul became known among the public via reports in local and European newspapers, important reactions occurred among statesmen.10 According to the statesmen of this period, the way to overcome this situation was to introduce legal regulations and models of administration that had been applied by cities in Europe, which “inspired admiration”, and to adopt the modern municipal implementations.11 Another aspect that made the modern municipality model attractive for statesmen was that it allowed the local administration to run its services supported by taxes which were directly collected from the local population, thus not creating a burden on the central government, which was already in financial difficulties.

During this period, in which the perception of centralization dominated state policies, the modernization of Istanbul was perceived as putting the city in order, establishing communication between various districts, and the beautification of the city. It was in this environment that the earliest examples of modern municipalities came to life in Istanbul. During the process of centralization, the Ottoman State met with the municipalities; this seems to be a contradiction when examined from modern principles, but in fact this was a different kind of centralization. What needs to be taken into account here is that the classical municipal organization allowed public initiative considerable leeway, but the structures of the municipality were established by “the State.”

The Establishment of Modern Municipalities in Istanbul

The Crimean War, which began in 1853, brought the problems of Istanbul to the top of agenda, thus leading to changes in the municipality, and the adoption of modern structures. After the arrival of the British and French navies in Istanbul, the foreign population in Istanbul increased. Many people came from Europe to Istanbul, as soldiers, reserve officers, reporters, health-care workers, diplomats, etc. The arrivals that were coming to the city because of the war were settled in the Beyoğlu-Galata districts. The newly-arrived foreigners often informed the government about their complaints; many of these complaints originated from the fact that the standards to which they were used to were not existent in Istanbul. They desired that Istanbul reach these same standards. The requests, coming from both Ottoman citizens and foreigners living in the Galata-Beyoğlu district, to introduce the modern municipality standards that were present in European cities had a great effect upon the changes in the administrative structure of Istanbul.

Establishment of Şehremaneti

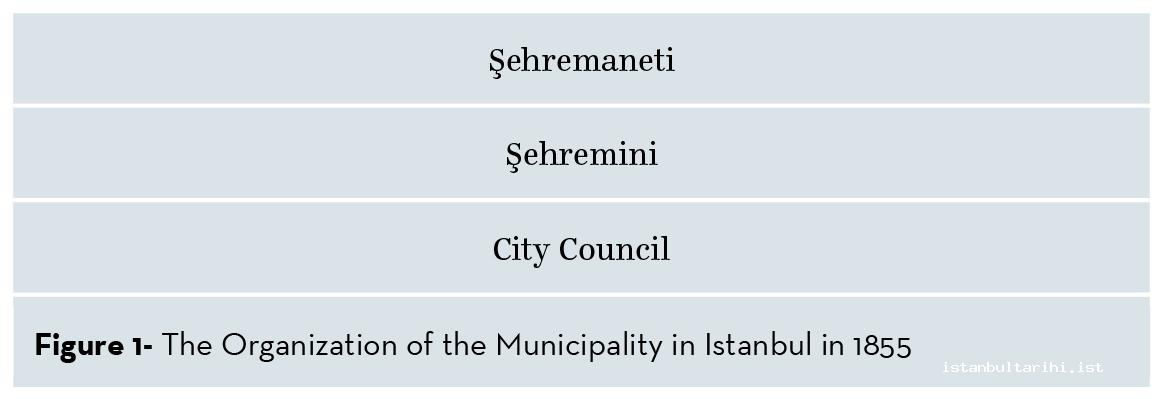

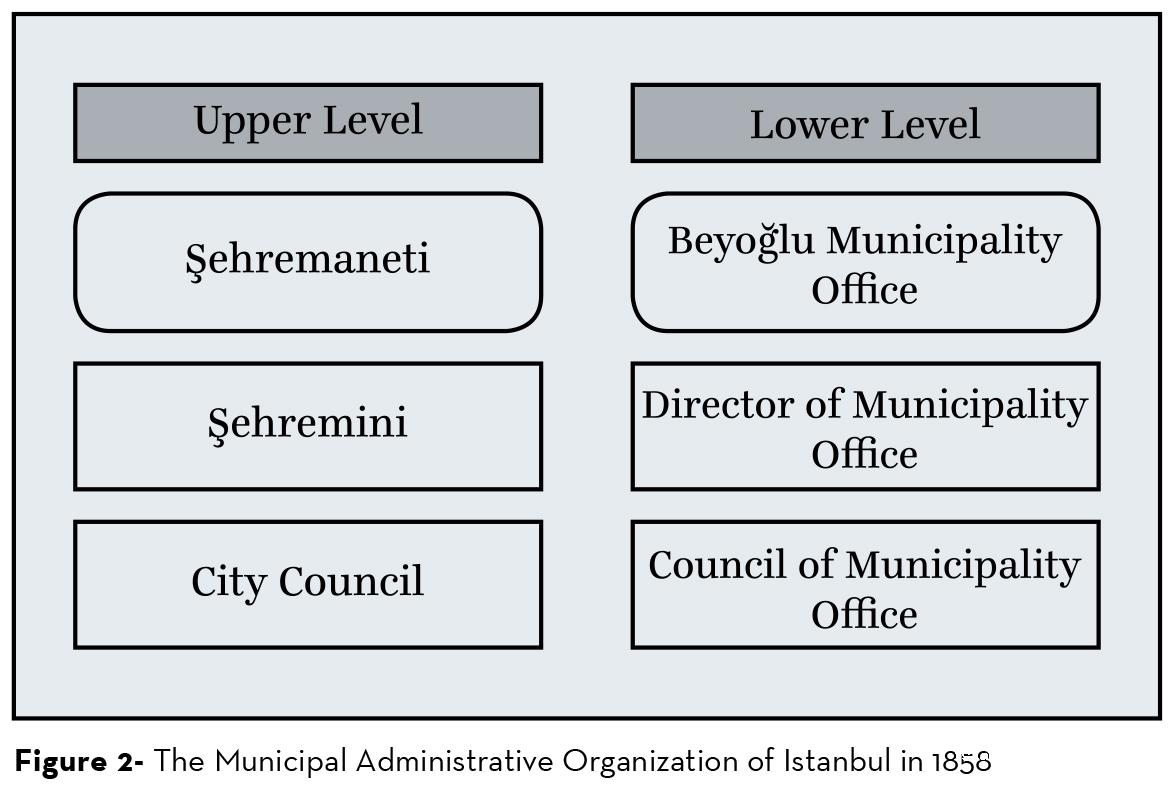

In order to find solutions to the problems that Istanbul was experiencing in providing local services, the Ministry of Ihtisab was abolished on August 16, 1855 and a new structure, known as the Şehremaneti, was established. This model, in which only one government body would be responsible for limited services for the entire city of Istanbul, was a one-step structure.

In Meclis-i Âlî-i Tanzimat (the Grand Council’s Reforms) ruling about the establishment of the Şehremaneti it was stated that due to the large number of foreigners coming to the city for the Crimean War municipal problems could not be ignored; this was a time when European eyes were fixed upon Istanbul. It was stated that the Ministry of Ihtisab had fallen short when faced by the extraordinary situation in Istanbul; thus, in order to find a solution, the Şehremaneti was established.12The operation area for the Şehremaneti was concerned with major matters, such as providing goods and foods stuff, organizing cleanliness and order in the market places and districts, and controlling prices.

During this period, the Şehremaneti was affiliated to the ministries of the central government; this association was in respect to the matters that the Şehremaneti was concerned with. It was affiliated with the Finance Ministry for the collection of revenues, most of which came from taxes paid by tradesmen, and with the Ministry of Commerce in matters related to the control and services of tradesmen; it was affiliated with the Ministry of Public Works and with the commission for the improvement of street maintenance (a part of the ministry) for matters related to construction, cleaning and development, and with the Ministry of the Gendarmerie for related to commerce and the police.

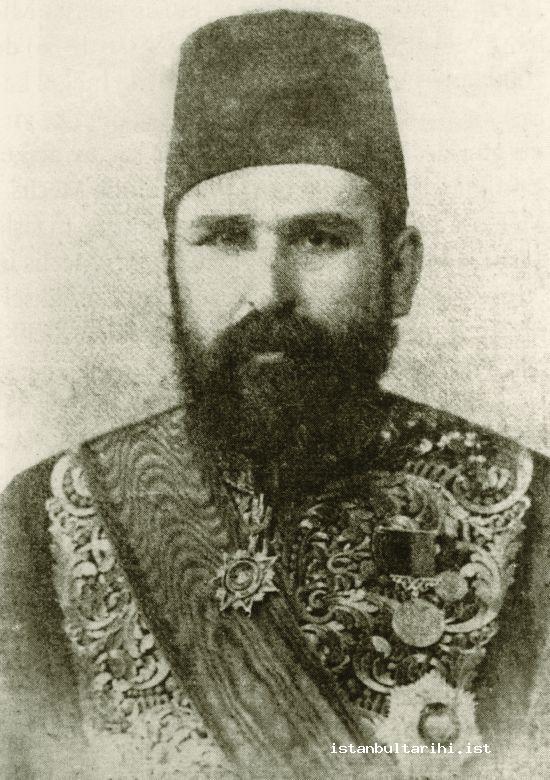

The prefecture of the city was established together with two sub-organizations, namely the şehremini (prefect of the city) and the city council. The şehremini, who had executive power, was selected by the Sublime Porte and appointed by imperial decree. Salih Efendi, who had worked as the police marshal and governor of Amasya, was appointed as the first prefect of the city. In some occasions, as in the appointment of the fourth prefect, Hüseyin Hasib Bey, the prefect was not appointed by the Sublime Porte, rather being directly appointed by the sultan.13

The şehremini, who was the head and executive power of the Şehremaneti, had different functions from that implemented by the office of prefecture in the classical period. The şehremini, one of the four emins (superintendents) of the palace during the classical period, was the officer in charge of restoration and construction in the palace; he was also responsible for some services related to the payment of the salaries and took care of palace needs. This office was abolished in the 19th century with the establishment of the Directorate of Imperial Buildings. Despite the differences in tasks and functions, the name şehremini was chosen for the head of the newly established municipal structure.

The şehremini, who was a government official, was a member of the Meclis-i Vâlâ (council of officials). There was no specific assigned task for the şehremini, but he was responsible for carrying out tasks that were given to the institution. Together with their assistants, the şehreminis inspected the markets and shops to check the prices were as they should be and that there was general order in the market. They were also given the authority to act as judges. In cases related to tradesmen, the şehreminis could send people to prison.

There were two officials called muavin (assistant) working under the şehremini. They would help him to carry out his duties. These muavin were also appointed. They would inspect the market and shops on behalf of the şehremini and act as the head of the city council when the şehremini was not present. These assistants were also automatically members of the city council. They also alternately acted as the head of a special council formed from the city council and hearing the cases related to the tradesmen.

The second division of the Şehremaneti was “the city council,” which functioned as an advisory and decision-making board. The council consisted of fifteen members, including twelve men who were appointed by the sultan, the şehremini and his two muavin. Candidates for the council were first chosen by the Sublime Porte from “subjects of every ethnic community” and from prominent tradesmen; these candidates were presented to the sultan and twelve people would be chosen and appointed to the council by imperial decree.

A system was adopted for the renewal of members to the council. According to this system, four of the twelve members were to be renewed every year. The membership of four members, determined by drawing lots, would be cancelled, and four people who were qualified to be member of the council would be selected and presented to the Meclis-i Vâlâ. After being approved by this council, the selected people were appointed to the council by imperial decree.

The city council was to meet twice a week; however, it was possible that the şehremini could call for an emergency meeting. The council was responsible for procuring the basic necessities, determining and controlling fixed prices, inspecting the market places and shops, maintaining cleanliness and order, and transferring the taxes collected by the prefecture of the city to the state treasury.

The matters decided by the council were classified as “Umur-ı Hayriye (charitable acts)” and “Umur-ı Külliye (general matters).” While decisions related to charitable acts could be implemented by the şehremini, those related to the latter had to be presented to the Meclisi Vâlâ; after being approved by this body they would be approved by the sultan, and only then could be implemented. Decisions of the council related to local public services, such as constructing and pavements, procuring basic necessities and deciding on fixed prices, were executed by the şehremini. In order to execute decisions related to central government services or the duties of the state, such as collection of taxes, the sultan’s ratification was necessary.

The yearly financial records of the Şehremaneti, which did not have a separate budget in the beginning, were overseen by Meclis-i Muhasebe (the Council of Accounting), which operated under the Ministry of Finance. The Şehremaneti had a similar financial structure to the abolished Ihtisab ministry. The Şehremaneti collected the taxes taken from tradesmen, which had been the duty of the Ihtisab, and transferred theses to the central treasury. Only a small portion of this revenue was left to the Şehremaneti. There were also taxes taken from the public in return for constructing roads and pavements and in return for animals used in transportation. During these early years, the revenues of the Şehremaneti could only meet the staff expenses. The financial deficit was made up by the central treasury. The institution had been established with significant expectations that it would be able to solve local problems in Istanbul; however, it was unable to attain equal financial power.

Parallel to its limited role in matters of local services, the institutional structure of the Şehremaneti also had a narrow scope. In addition to the main institutional departments, such as dispatch and accounting, units which issued certificates of iskan (housing) and müruriye (tolls) were organized in the structure of “oda (associations)”. Engineers were employed to carry out those services in which the Şehremaneti had as yet a limited role, such as constructing the roads and pavements, and repairing the water ways and sewer system. In addition, there were employees who were responsible for the public inspection and central administration tasks of the Şehremaneti. Tahrirat Odası (The secretarial services,) Muhasebe Odası (accounting services,) Tezkirehane (official certificates), Yoklama Odası (inspections), Mürur Odası (tolls), Jurnal Odası (the Informer’s Report), Hane Odası (house), and Liman Odası (harbor) were the main offices of Şehremaneti.

The Şehremaneti, which had been established to solve the local service problems in Istanbul, was a continuation, in respect to its functions and authority, of the Ihtisab Ağalık and the Ihtisab Ministry. During this first period, the Şehremaneti did not possess a strong characteristic as a unit of local administration that had administrative and financial autonomy and which was based on political representation. Having authority in only a limited number of local services, the few financial resources, and the fact that it was structured as a unit the operated under the central government limited the ability of the Şehremaneti to produce solutions for the large-scale problems which emerged during the process of change in the city.

The Commission of City Order and the Search for a Model of Municipality

The success of the Şehremaneti, which was established to improve local services, did not live up to expectations in the areas of its main responsibility, such as construction, development, inspection of tradesmen, and providing the vital needs of society. In a report related to this matter,14 although Istanbul, which was one of the most important cities of the world, was the center of the caliphate and the sultanate, it was criticized for being below the expected level in the most important matters, such as construction, as well as the order of the streets and markets. In particular, comparing Istanbul to European cities and the services they provided, the report stressed the need for new institutions that would not be a financial burden; these institutions would carry out higher levels of services, described as tezyîn (decoration), tevsi’ (broadening), tanzif (cleaning), tenvir-i esvak (illumination of streets and markets) and ıslah-ı usul-i ebniye (improvement in construction methods).

In the face of the increasing problems in the local services of Istanbul, the central government embarked on a search for a new municipality model. According to the government, the Şehremaneti had been unsuccessful in applying the European municipal model in Istanbul. It was accepted that the main reason for this was that the members of the city council lacked sufficient knowledge and experience to introduce a municipal administration. Moreover, the city council had failed to offer a tangible model for the new municipality of Istanbul. Upon this, it was suggested that a commission be established; this commission would be made up of local and foreign residents of Istanbul, people who were knowledgeable about the problems of municipal administration. In this way, a new municipality model for Istanbul could be prepared.15 Upon the ratification of this suggestion by the sultan, in 1856 the İntizâm-ı Şehir Komisyonu (Commission Municipale) was established according to an imperial decree. This commission was headed up by Emin Muhsin Efendi and included the following members: Antuvan Alyon, Kamando, Hüseyin Hüsam, Rovelaki, Ferhad, Mıgırdıç, Harmanos Veledi Yusuf, Mehmed Salih, Franko Ben Bericole and Refik Mustafa.16

The İntizâm-ı Şehir Komisyonu was not only a reform commission, but was also important due to its activities in public works, such as establishing routes for new roads, opening new roads, restoring old ones, constructing pavements, offering new methods of road construction, illuminating the cadde-i kebir (main thoroughfares), and regularly collecting waste. In finances, in order to create revenue for the Şehremaneti, taxes started to be collected from animal and cart owners and new regulations were introduced to ensure that home and shop owners contributed to the costs of pavement construction. These works were carried out particularly in the Galata-Beyoğlu district. Not only was the commission unable to complete many projects, due to the fat that it did not produce any tangible suggestions for the municipality model, its activities were brought to an end. Another new commission, with seven members, was established.

The new commission prepared a seven-article report on how to improve the structure of the municipality. Perceiving that foreign support was essential for the reforms in the Istanbul municipality to succeed, in its report the commission stated that it was necessary to have representatives from the relevant country contribute to the project. Moreover, some limited solutions were offered to solve the problems of the city related to water, roads, paving, lighting, and cleaning. The most important work that the new council produced was the suggestion for a new model that would be the basis of the municipality for the next period. According to this model, Istanbul would be divided into 14 district, and the Şehremaneti; a municipality would be established in each district (belediye dairesi). Thus, these district municipalities would be responsible for local services, while the Şehremaneti would carry out duties related to the entire city of Istanbul. Suggestions developed by the commission were mostly related to improving the quality of services, rather than ensuring autonomy. The “Belediye Dairesi (departmental municipality)” model offered by the commission played a pioneering role.

Transition to a Two-Level Administration Structure

The suggestion made by the municipality commission to govern the city of Istanbul according to a model consisting of the Şehremaneti and district municipalities was welcomed also by the central government. An official report stated that it was not enough to merely construct sidewalks and pave the roads in Istanbul, it was also necessary to establish institutions that would make infrastructure investments like sewer systems and the laying of water pipes, and which would assume continuous responsibility for these services. The idea to divide Istanbul into districts which would support one another in dealing with the municipality services of the city and the policing, and the collecting them under one administration was ratified.

Just like its counterparts in Europe, the leading approach to municipality reform in Istanbul became giving local services over to the care of an administration that was formed from members of the local public. In this way, it was hoped that improvements in services, as well as the creation of the finances that would be required could be achieved without burdening the central government. In such an environment, the model of “district municipality”, which would provide services in keeping with the practices of the Ministry of Ihtisab and the Şehremaneti was ratified by the government. Although in principle, elections were to be used to select the municipal district head and council, suddenly it was accepted that the method of appointment should be by the government, based on the idea that election was not practical.

The establishment of 14 districts in the Istanbul municipality was not agred upon; this was a new way of administration which would be applied for the first time and it would cause new financial burdens. Instead of this, a pilot scheme was adopted. The Galata-Beyoğlu area, where the most diverse social composition existed, was selected as the pilot region; this was the region where commercial and financial institutions were most densely located and was Istanbul’s window opening onto Europe. The main reasons given to justify this choice were that there were many profitable buildings in Galata and Beyoğlu, many people who had experiences in different kinds of municipality administrations from a number of countries resided here, and there were also some affluent people living here who could help meet the municipality’s expenses.

During the first division of Istanbul into district municipalities, in 1857 a municipality district called “Beyoğlu” was established in the district of Galata-Beyoğlu. When Istanbul was divided into 14 districts, Beyoğlu formed the sixth region, which is why it began to be known as the “Altıncı Daire (Sixth District.)” The regulations known as the “Altıncı Dâire-i Belediyye Nizâmâtı (Regulations of the Sixth District of Municipality)”17 and “Beyoğlu ve Galata Dairesi’nin Nizamı Umumisi (the general regulation of the Beyoğlu and Galata district)”18 set out a broad legal framework for the municipality, setting out their duties, authority and financial structure. This legal framework also acted as an example for the municipalities that would be established in rural areas.

The government took the negative experiences of the Şehremaneti into consideration, and affiliated the new municipality not to the Şehremaneti, but rather directly to the grand vizier. As a result of this regulation, the new municipality was able more easily able to overcome many of its difficulties with the highest level of support from the central government. For example, the authority to carry out development within the borders of the municipality was taken from the Directorate of the Imperial Buildings, which was at this time responsible for construction works, and was given to Altıncı Daire. Unlike the Şehremaneti, this district was given the authority to collect estate tax, thus demonstrating its privilege in finances. Despite all these privileges that Altıncı Daire had, there were many administrative regulations which required the permission of the Sublime Porte. Some of the most important of these can be listed as follows: inspection of annual revenue and expenditure tables, permission for a great amount of extraordinary expenditures, new taxes and the appointment of officials.

Two organs, that of müdür (director) and Daire Meclisi (district council), were established under the administrative structure of Altıncı Daire. The müdür, who was equal in status to a government officer, was appointed according to a suggestion from the Sublime Porte and on the approval of the sultan. Those who were to be appointed as müdür were selected from among those who were eligible to be chosen for the council. The primary duties of the müdür included the administration of the municipality, chairing the district council, carrying out communication between the council and the office of the grand vizier, the execution of decisions taken in the council, calling the council for a meeting when necessary and authorizing accounts.

The daire meclisi was the decision-making body; this body was made up fifteen members, including the müdür, seven full members, four consultant members, two assistant managers and a translator. To be eligible for the council, an individual had to have 100,000 kuruş worth of property within the borders of the district, have be a resident of the district for at least ten years, and be knowledgeable about municipality affairs. A list of people with these qualifications would be prepared, having more names than positions in the council, and presented to the sultan by the Sublime Porte. The names approved by the sultan would be appointed as the members of the council. Consultant members would be appointed after undergoing the same process. Half of the council members would be reappointed every two years with the same method.

The requirements for being a council member were developed within the context of examples from Europe, and became the prototype for division based on property, which would become widespread in future municipal councils. To be a citizen of the Ottoman Empire was not a condition for membership. With this regulation, the citizens of foreign states also could be given a place on the council. Parallel to this regulation, the social composition of Altıncı Daire was taken into consideration; it was decided that the minutes of the council meetings would be recorded in French as well as in Turkish.

The responsibilities of the district council were listed as follows: inspection of the places, such as fairs, theaters, markets, restaurants, schools, ballrooms, coffee houses and bars; cleaning the district municipality; opening new roads and widening and restoring already existing ones; constructing pavements; establishing a sewer system; washing the streets; controlling and protecting the waterways; checking the scales and other measuring instruments; demolishing old and dangerous buildings; inspecting the sales of cereals, which were basic needs for the people; controlling revenues and expenditures; being responsible for contracts related to municipality businesses; collecting taxes.

In the sub-organization of Altıncı Daire there were two assistant managers who were responsible to the manager and the council. Tasks related to official correspondence and documents were the responsibility of a unit consisting of a head clerk and clerks. Doctors, consultant members of the council, were responsible for activities related to the public health. Architects and engineers of the district coordinated district maps and carried out building activities in the district. District financial matters were the responsibility of the treasurer and the officers under his command.

Altıncı Daire, which used the financial opportunities provided by a high level of means provided by the state well and which constituted an economically powerful section of the city, was relatively successful. Some of its important achievements were the completion of the cadaster, the organization of Karaköy square, the planning and construction of places that had been damaged in fires, illuminating some streets with gas lamps, constructing a slaughterhouse, cleaning the streets, building a garden in Taksim and opening new roads.19

The successful works carried out by the new municipality established in Beyoğlu created a demand for municipality administration in other parts of Istanbul. Tarabya which had first been a summer resort for Beyoğlu but after the improvement of the means transportation were attached to its daily life became the second place where a municipality administration was established. Even though Tarabya was not among the 14 districts where a municipality had been planned to be established, as a result of the application of its prominent members to the Sublime Porte was conditionally accepted and a municipality district was founded in Tarabya in 1864. These conditions were not to put an extra financial burden upon the poor population of Tarabya, not to borrow exceeding the budget limits of the district, not to charge taxes from poor peoples’ houses whose rent was lower than 500 kuruş, and not to collect the regular taxes higher rates than % 2 and extraordinary taxes higher rates than % 3. By making limited changes in the legal regulations of Beyoğlu, a peculiar legal regulation was prepared for Tarabya.20

Tarabya municipality carried out the activities such as cleaning the streets, constructing roads and pavements, lightening streets by petroleum lanterns, and opening a public garden with the local taxes and donations collected from the affluent members of the region. Improvement achieved by the municipality in such a short period of time and its efforts to organization had also reflections in the presence of the state.

Following Tarabya, a municipality administration was established in Adalar upon the application of the headman and prominent members of the public in 1867. Adalar municipality district was constituted from Büyükada, Heybeliada, Kınalıada and Burgazada where non-Muslim community densely lived. As a reflection of the social structure of the region the district manager and the council were formed from non-Muslims.21

Materializing the Municipality Model in Istanbul

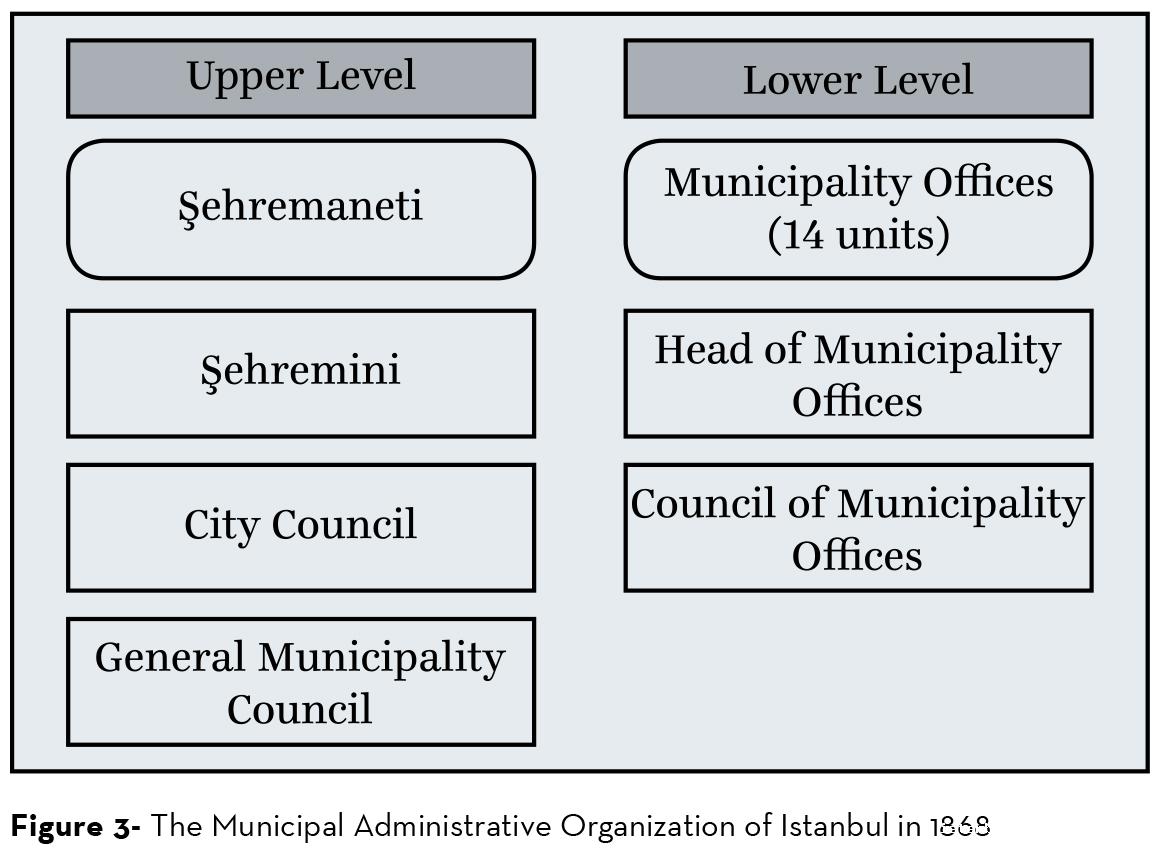

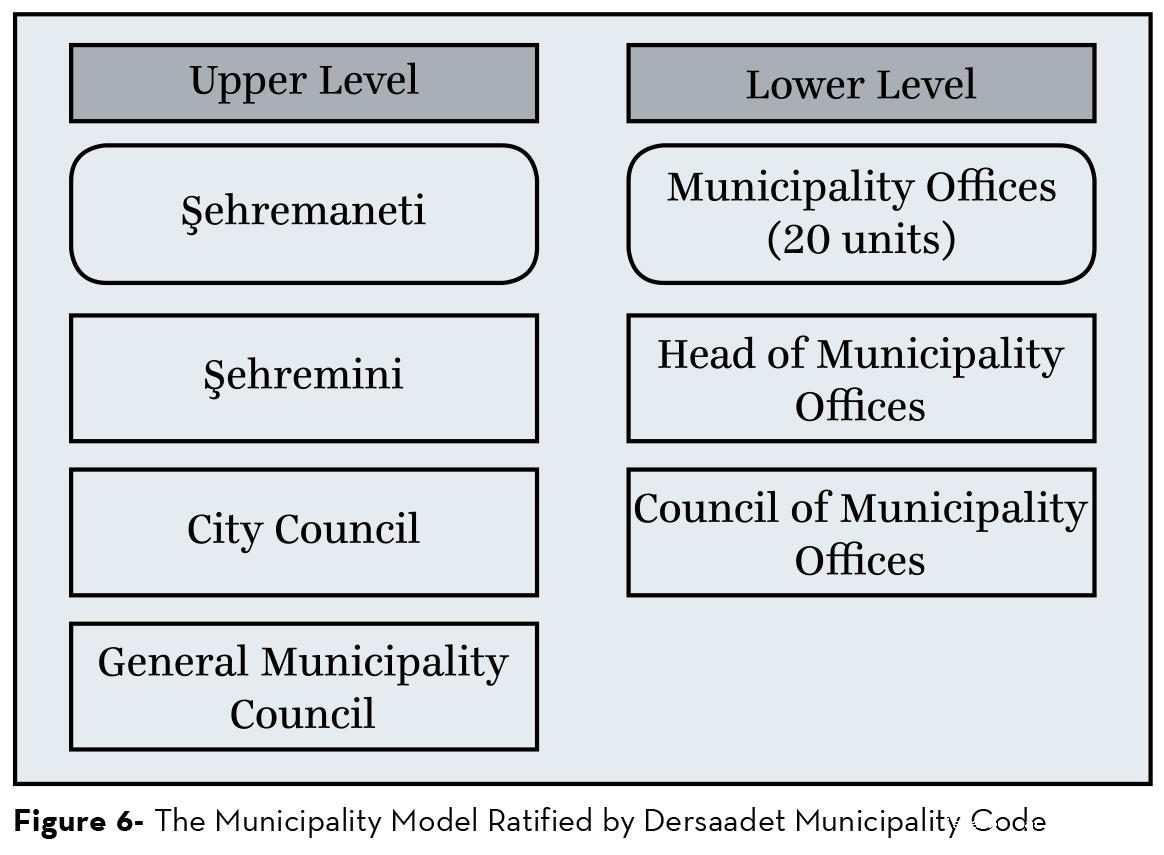

The success of the Beyoğlu municipality, which was the first administration of the city through a model based on the Şehremaneti and municipality districts, and the relatively successful activities of the Tarabya and Princes’ Island municipalities, which were established later, increased trust in the new model. The authority gap in basic issues, in particular, the inspection of tradesmen, cleaning, maintaining the roads, municipality works, was filled by the new institutions that were in charge of these duties; this led to an increase in the legitimacy of the Şehremaneti-district municipality model in the eyes of both the public and the state. During this period, in which Midhat Pasha, Âlî Pasha and Fuad Pasha were influential on the Şûra-yı Devlet (state council) and in the bureaucracy, the Şûra-yı Devlet prepared a law proposal to spread district municipalities throughout Istanbul. After the sultan ratified the code on October 6, 1868, the Dersaadet İdâre-i Belediye Nizâmnâmesi,22 consisting of 63 articles, came into effect.

This was a legal document that was supported by the efforts of Ottoman statesmen to bring Istanbul up to the level of European cities. The reform process that began with the establishment of the Şehremaneti and continued with the establishment of the İntizam-ı Şehir Komisyonu (city order commission) and district municipalities, was presented as a solution to the confusion about authority for responsibility of the services; this was considered to be the source of problems experienced in local services. The code was an important text which discussed the municipality borders, functions, structural features and other rules in one regulation. In this code, which brought many functional and organizational changes to the municipality structure of Istanbul, other than some limited changes, the main structure of the Şehremaneti remained as it had been established in 1855; the Beyoğlu district municipality was used as a model for the 14 municipalities that were to be established.

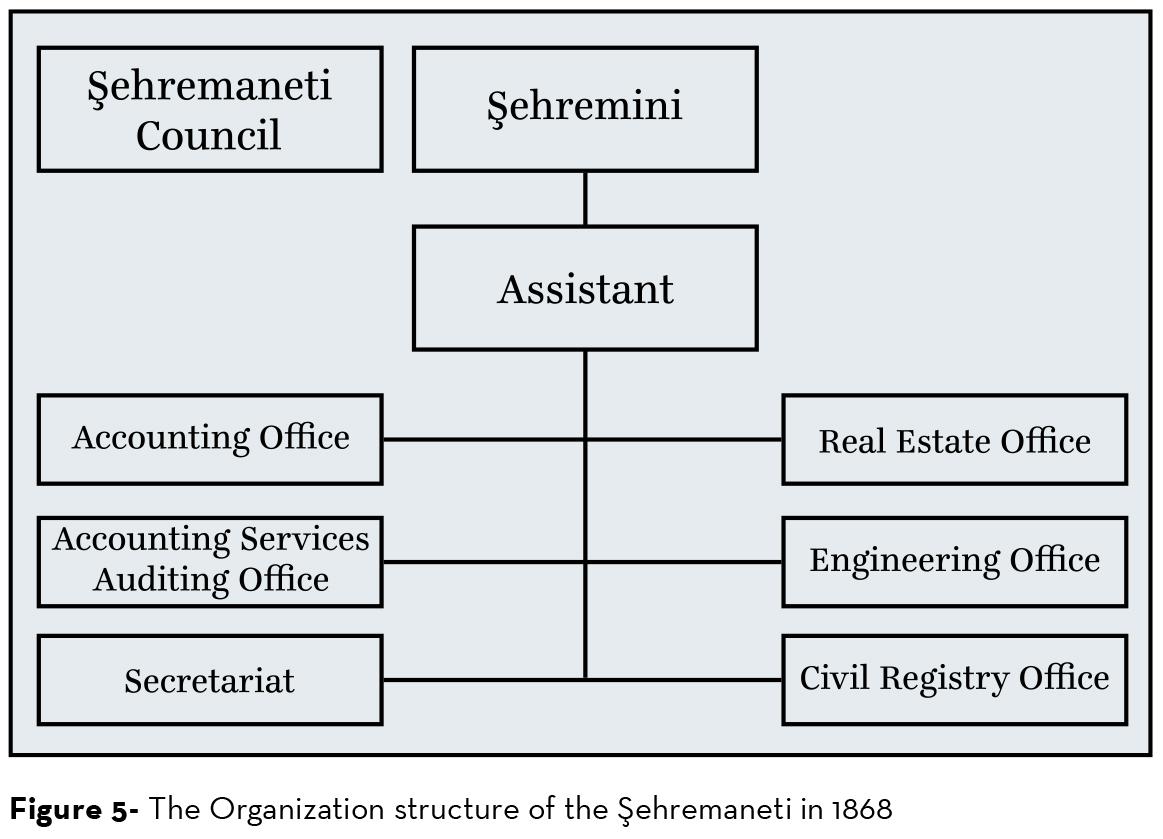

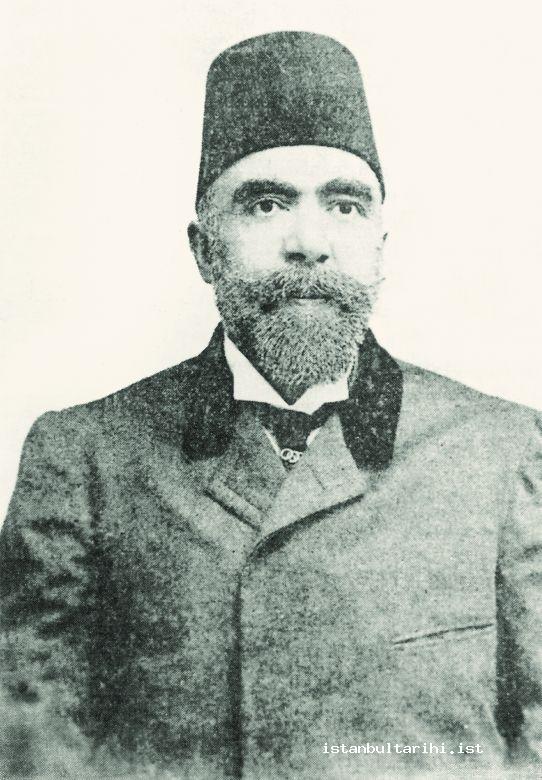

The organizational structure of the Şehremaneti, which was formed by the şehremini and the Şehremaneti council, was maintained. Readopting the former method of appointing the şehremini, as well as his status as executive, this position was defined as a government officer who was suggested by the Sublime Porte and appointed by the sultan. Unlike previous regulations, a new definition was introduced for the duties and the limits of the authority of the şehremini. At the top of the hierarchy of the Şehremaneti, the şehremini was now a rather powerful position, and had the authority to abolish district councils, as well as financial and administrative powers in district municipalities. Server Pasha was appointed as the first şehremini of this period. The title “şehir meclisi (city council)”, which was the second agency of the Şehremaneti, was changed to “Şehremâneti Meclisi (the council of Şehremaneti).” The method of choosing the six members of the council was via suggestion by the Sublime Porte and appointment by the sultan; this was adopted and maintained in the same manner.

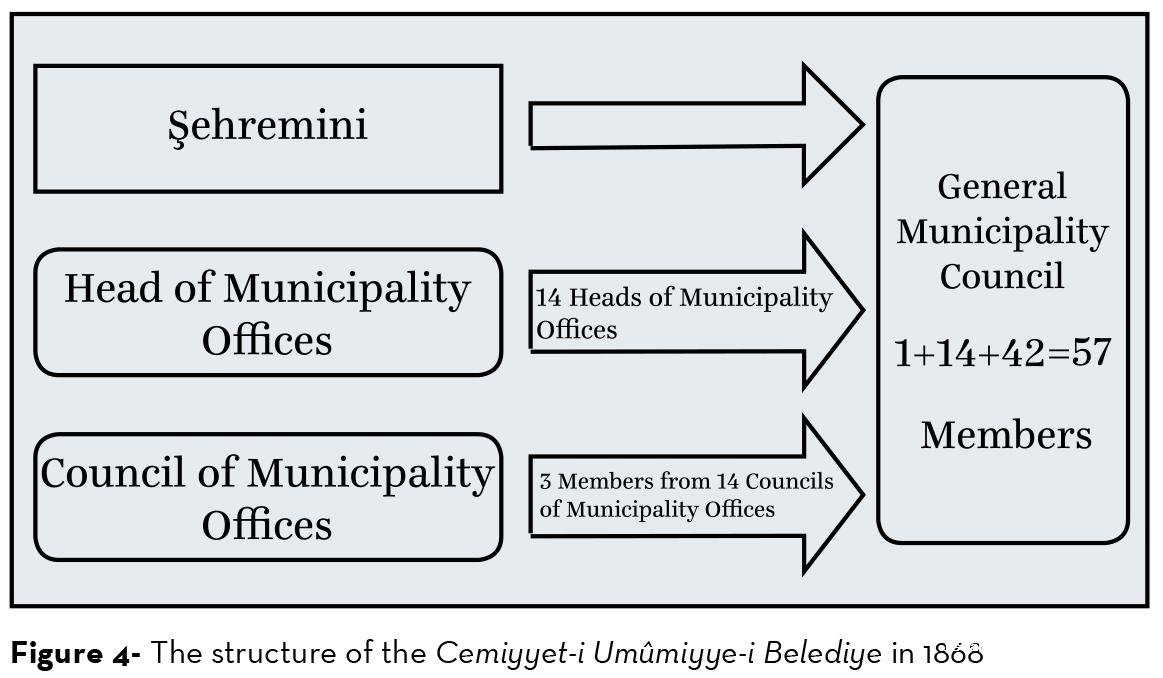

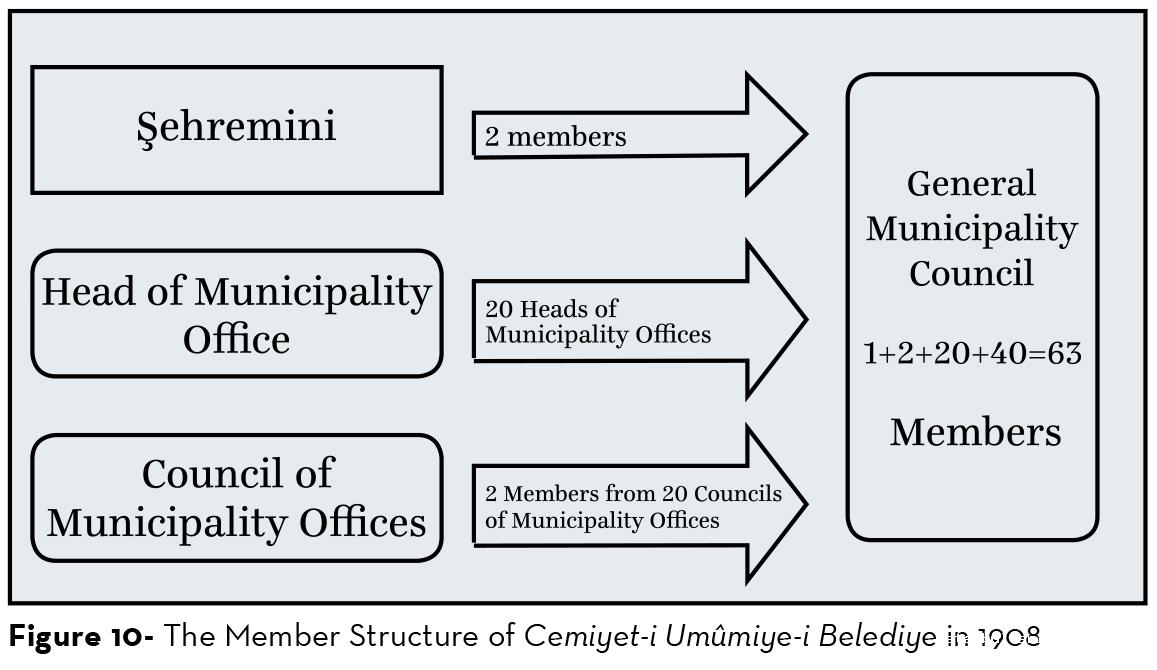

The greatest innovation introduced by the 1868 regulation was the foundation of a new council structure known as the Cemiyet-i Umumiye-i Belediye (Union of the Public Municipality). In a two-part legal structure, composed from the Şehremaneti and district municipalities, this council provided coordination and control. This new council consisted of 57 members, who were headed up by the şehremini, managers of the district municipalities, and three members chosen from each municipal council. This council, which was to meet biannually, discussed budgets, expenditures and the financial state of the Şehremaneti and district municipalities, as well as examining their requests for loans and large-scale development projects. Another important function carried out by this council was the preparation of draft laws related to municipal issues.

As not all the district municipalities that had been planned were brought to life, the cemiyet was unable to open during this period. While the planned administration system could provide benefits in the coordination of the planned administration system, it was weak in the matter of carrying out inspections. The main problem was that the members in charge of inspection were also the representatives of the bodies to be inspected. In fact, even after the declaration of the second Meşrutiyet and the establishment of the cemiyet, this issue would lead to a great deal of discussion.

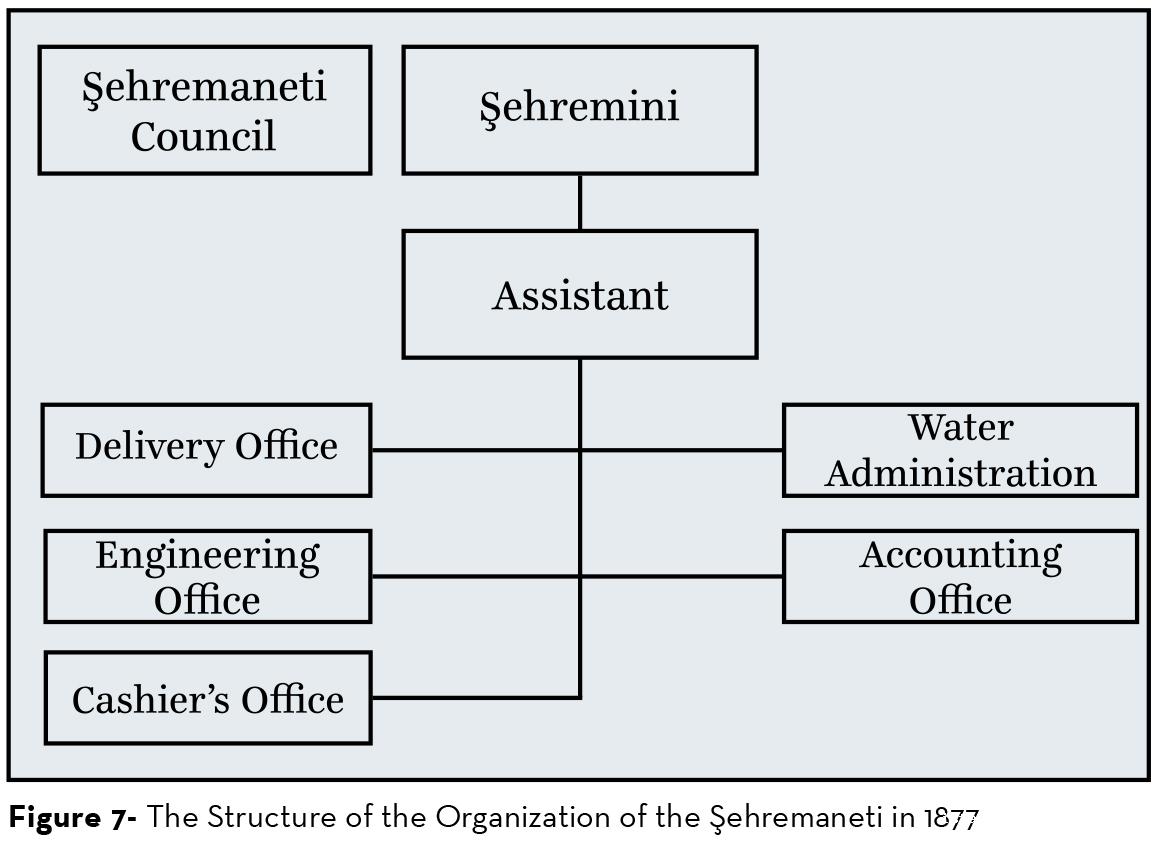

The structure of the Şehremaneti was reorganized in 1868. According to the new structure, in the hierarchical order, muavins (assistants) came after the şehremini. Muavins, who chaired meetings at which the şehremini was not present, had a powerful position in the institution. Parallel to its heightened responsibilities, the organizational structure of the Şehremaneti, which had a simple and functional structure in its early years, was also broadened. The main service units consisted of accounting and real estate offices, auditors, a water management commission, engineering, and a civil registry.

As most of the responsibility for development work was transferred to the Şehremaneti, the ebniye meclisi (building council) was established.23 Until 1868, the construction and road works of the Beyoğlu district were carried out by the directorate of imperial buildings. After this year, these duties were transferred to the Şehremaneti. Moreover, the ıslah-ı tarik (road improvements), which functioned under the Ministry of Public Works and took care of the restoration of places that had been damaged by fire and the construction of new roads, was abolished. The water administration was also transferred to the Şehremaneti, along with its budget. Efforts continued to establish a “Mühendishane” (engineering office), to prepare a regulation related to construction matters, and a special office to supervise construction, known as the called Keşif Kalemi (Survey Office) in place of these earlier offices.

After the 1868 Dersaadet İdare-i Belediye Code (Istanbul Municipality Management Code), the multiple-headed position of the Şehremaneti within the structure of the central administration. In the Ministry of Internal Affairs dated 186924 it was clearly stated that Şehremaneti worked under the Ministry of Internal Affairs.

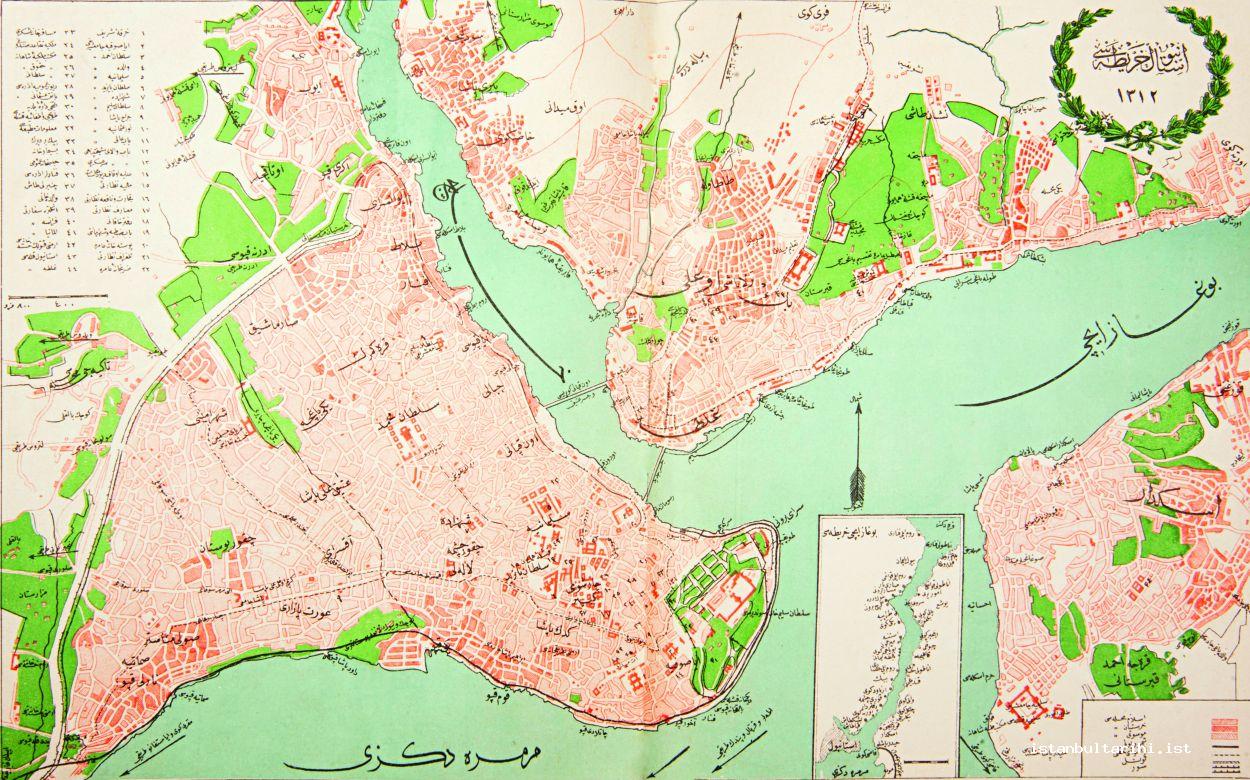

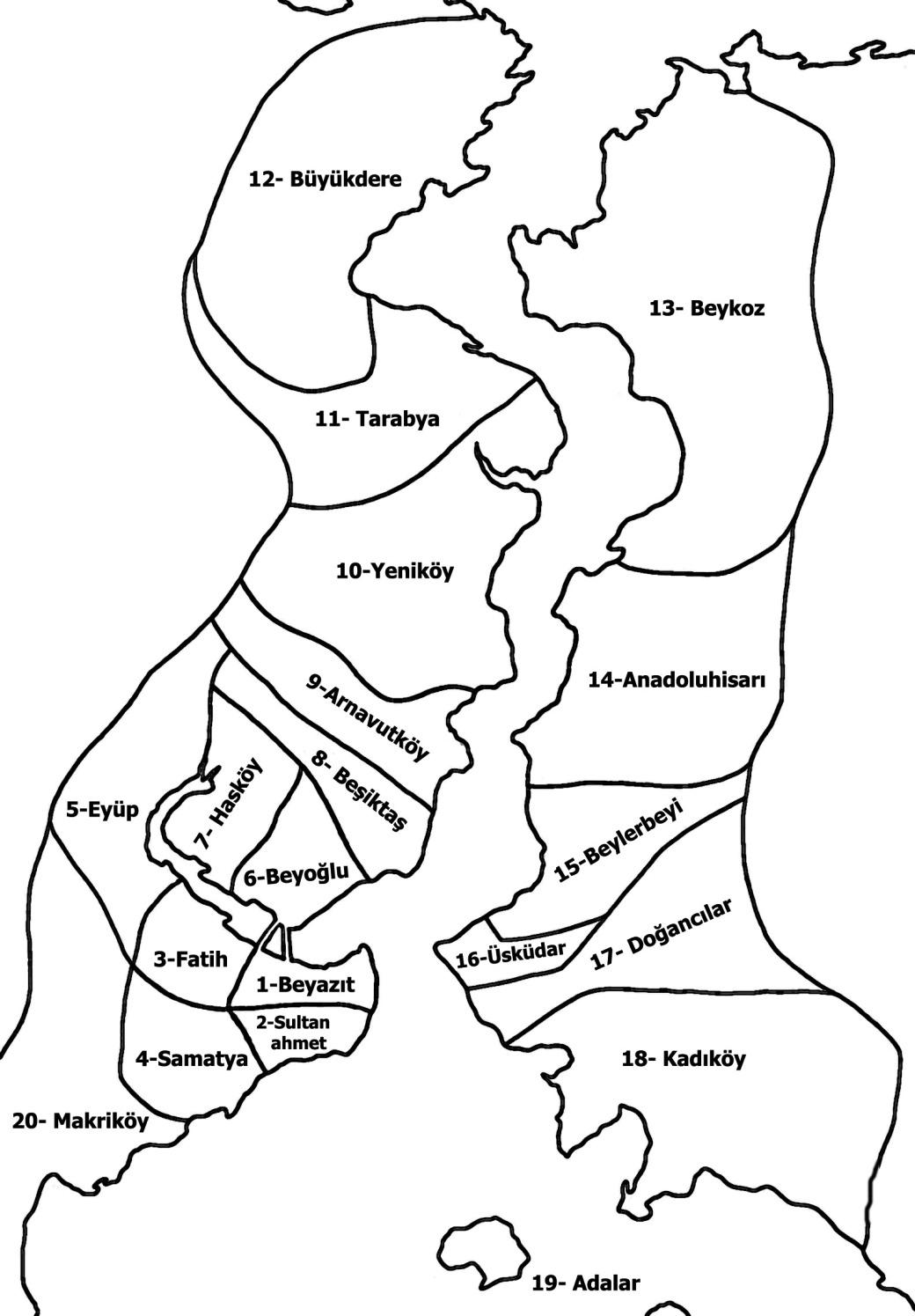

With the Municipality Code dated 1868, a new model which was dividing the administration of Istanbul into 14 municipality districts was established. According to this new division three municipalities were to be located in the city walls, and three on each side of the Bosporus; three more municipalities were to be located outside the city walls on both sides of the Golden Horn. Kadıköy, an important residential area in Istanbul, and the Princes’ Islands, which were connected to the city despite the obstacle of the sea by the Şirket-i Hayriye ferry-boats, also had a new municipality established. All fourteen municipalities were within the borders of the Şehremaneti. The borders of the district municipalities were divided in a way that was unlike those of previous municipalities, which had been based on the areas of authority of the qadis and naibs. According to this new division, the borders of the municipalities were not determined based on realistic criteria; level of income, density of population, topographic features and distances were not taken into account.25

The municipality structure, which had begun with the Altıncı Daire and in which all services were carried out by the agencies of belediye daire müdürü (the municipal district manager) and a council, was accepted as the prototype for the new structures. Working under the Şehremaneti, the district manager, who was appointed by the sultan, was responsible for fulfilling the duties and authorities as set out by the law. As he was appointed by the central government, the manager’s salary was paid by the state treasury.

|

Table 1- Municipal Departments that were to be Established in Istanbul in 1868 |

|||

|

District 1 |

Ayasofya |

District 8 |

Mirgun |

|

District 2 |

Aksaray |

District 9 |

Büyükdere |

|

District 3 |

Fatih |

District 10 |

Beykoz |

|

District 4 |

Eyüp |

District 11 |

Beylerbeyi |

|

District 5 |

Kasımpaşa |

District 12 |

Üsküdar |

|

District 6 |

Beyoğlu |

District 13 |

Kadıköyü |

|

District 7 |

Beşiktaş |

District 14 |

Adalar |

The general decision-making organ within the district municipality was the council. The number of the council members ranged from between eight to sixteen, depending on the size and importance of the district. The municipality code, dated 1868, meant that for the first time the council members were to be elected. In this way, the local populace now had a role in selecting the council members, even though it was a model with limited participation, based on property ownership. Although elections were not carried out during this period, this regulation was important in that it legalized elections for determining the council members.

The control of the election process was to be implemented by “an Election Commission,” which had functions similar to counterparts in the contemporary world. The conditions for being eligible to vote for council members were: being over 21 years old and owning property that could generate more than 2,500 kuruş revenue in a year. Different requirements were established in order to be elected to the council. Those who owned land that generated 5,000 kuruş per year, who were over 20 years of age, who had not been convicted for murder, who were not an employee in one of the district municipalities or in the Şehremaneti, who were not a developer in one of the district municipalities, and who did not carry out any duties in court or work as a lawyer were eligible to be candidates. Members would be elected for a period of two years to the council.

Even though fourteen district municipalities were to be established in this period, not all of them were established. In addition to the municipalities of Beyoğlu, Tarabya, and the Princes’ Islands, which had been established before the introduction of the code, the newly established municipalities remained limited to Yeniköy, Beykoz, and Kadıköy. As a result of the positive applications in Tarabya, immediately adjacent to Yeniköy, leading members of Muslim and non-Muslim communities applied to the government and requested to be able to establish a municipality administration. This request, which was examined by Şûra-yı Devlet (the State Council), was approved provided that these administrations would not be a burden on the treasury. With the opening of the municipality council, composed from leading members of society, at the end of 1873, the municipality was established in Yeniköy. As a result of the process that started with the application by the people of Kadıköy and Beykoz in 1875, the establishment of municipality administrations was approved, with the condition that the tax revenues were sufficient.26

The duties laid out in the municipality code of 1868 introduced significant improvements as compared to previous regulations. The Şehremaneti and the district municipalities went beyond the limited functions of the Ministry of Ihtisab and were organized as administrative units with responsibility for most of the local services. However, sharing the responsibility of the services with central institutions, like the Ministry of Awqaf and Public Works was not completely abolished.

Despite several important regulations that this law introduced, their application was not as successful. There continued to be problems in local in Istanbul. The municipalities, which were still in the establishment stage, did not have the structural or technical substructure to carry out the functions as set out in the law. During this period, to a large extent, the Şehremaneti continued to follow the administrative approach and application of the Ministry of Ihtisab. The Şehremaneti, which lacked the institutional capacity, knowledge and experience to fulfill most of the tasks and duties that fell to it, did not proper make use of its financial.

The failure to establish the municipalities that had been planned, which was the essential foundation of the municipal structure in Istanbul, prevented the Cemiyyet-i Umûmiyye-i Belediyye from opening. It was intended that this body would be formed from the members of the district councils. The model, as set out in the Municipality Code of 1868, could only be applied to a limited extent. This negatively affected and delayed the institutionalization process for the municipalities. The existence of the newly established municipalities in the affluent parts of the city, where most of the residents were non-Muslim, and the authority gap in the local services in other parts of the city created a contradiction.

During this period the financial problems experienced by the state had negative effects upon the municipalities, both in terms of structure and local services. While district municipalities had few personnel, in an attempt to limit expenditure, the Şehremaneti took on a number of functions and thus assumed a more central role. Even though the system was not fully functional, the Municipality Code of 1868 constituted an important step in the process of reorganizing local services with a modern understanding.

The Structure of the Municipality in Istanbul during the First Constitutional Monarchy

One of the turning points in the Ottoman State was the declaration of the Kanun-i Esasi (Constitution) in 1876 and the beginning of constitutional monarchy period. The Kanun-i Esasi, which regulated an administrative system that was based on a constitutional monarchy, was a wide reaching text consisting of 119 articles. This constitutional text adopted an administrative structure based on provinces; there was also a conceptual framework concerned with future regulations and practices. According to this framework, basic principles in the administration of the provinces were the concepts of the “scope of authority” and “separation of powers”.

Rules about the municipalities were regulated in Article 112 of the Kanuni Esasi, under the title Vilayat (Provinces). According to this article, the provision of local services was to be administered by the municipal councils formed from elected members. Legal details, such as the municipalities’ functions, organization, financial structure and election methods, were to be set out in the legal regulations enacted by the Meclis-i Mebusan (Council of Deputies).

Giving the responsibility for local services to the elected municipal councils in a constitutional text was an important point in the transition to the modern municipal structure in the Ottoman State. This regulation demonstrates that municipalities and, more particularly, councils were adopted as the valid model for reorganizing local services in cities; development would be around this axis.

The Dersaadet Municipality Code and Administration Model

In his opening speech for Meclis-i Mebusan (the Council of Deputies,) Sultan Abdulhamid II stated that the laws related to Istanbul municipalities and provinces had been included in the proposals sent to Meclis by the government; furthermore, this body would be instrumental in approving it. This statement was the first sign that the municipalities would be reorganized, as had been briefly mentioned in the constitution. Subsequent to this, a draft municipality law for Istanbul was prepared and sent to the Şûra-yı Devlet. The draft was discussed in the Şûra-yı Devlet Tanzimat Dairesi (State Council Reform Office), and after some minor changes, was presented to the Meclis-i Umumi (General Council). There was debate during the meetings of Meclis-i Mebusan and the Meclis-i Ayan (Senate) concerning issues such as the share that the municipality would have in estate tax, the method of selecting the head of district municipalities from the elected council members, the management of municipality debts, the conditions that new members had to meet in order to be elected, and the limitations imposed on the district municipalities. This new regulation, accepted after some debates and approved by the Meclis-i Vükelâ (Council of Ministers), went into effect as Dersaadet Belediye Kanunu, being promulgated in an imperial edict on October 5, 1877. During this process, another code, entitled Vilayet Belediye Kanunu (Province Municipality Code) was introduced for provincial municipalities. These two codes, which were accepted for the municipalities of Istanbul and the provinces, were important regulations that the Turkish Republic inherited from the Ottoman State, remaining in effect until 1930.

Although the Dersaadet Belediye Kanunu was a new regulation, it did not bring radical changes to the municipal model. It was a legal regulation that aimed to develop and bring maturity to the structure that had begun with the Şehremaneti in 1855, continuing with the Beyoğlu District municipality, and becoming concrete with the municipality code of 1868. The administrative model of Istanbul, consisting of the Şehremaneti and district municipalities, was adopted as it was. This was an important regulation that ensured the municipalities were now full legal entities.

The şehremini was the head of the Şehremaneti and the executive power, as it had been previously. The şehremini, whose period in office was not limited, was appointed by the sultan, as they had been before. As there was no time limit for the şehremini and as they were appointed, it was also possible for them to be removed from their office at any time. The main tasks of the şehremini were to preside over the council of the Şehremaneti and the council, prepare the budget and present it to the council, be the official who had the authority to ratify accounts, to appoint and dismiss the officials, to inspect district municipalities, and to ensure that the police and military forces carried out their duty in related matters when necessary. The şehremini were also authorized to disband the district municipalities, thus being given a very powerful position.

The council was the main decision-making organization of the Şehremaneti. The members of this council, which was formed from a head and six members, were appointed by the sultan. Even though it was stipulated in Dersaadet Belediye Kanunu that the members of the district councils were elected by the public, the members of the Şehremaneti council continued to be appointed. Unlike the 1868 Municipality Code, one of the members of the council was to be an engineer from the Erkan-ı Harbiye (general staff) and another one was to be a doctor from Mekteb-i Tıbbiye Nezareti (the Ministry of Health, Medical School). The structure of the Şehremaneti, which people had thought would be more effective in the administration of the city, was formed in accordance with the control and coordination needs of the central government due to problems previously experienced in the health and development of the city.

The tasks of the Şehremaneti were widely defined, e.g., discussing matters related to the administration of the municipality; discussing matters for which district municipalities had asked permission, conducting primary investigation into complaints about municipality officers and sending these to court, examining the Şehremaneti budget, annual records and expenditure tables, approval of the same, classifying the streets into degrees based on the Ebniye Nizamnamesi (Building Regulations), approving road maps prepared by the district municipalities, resolving disagreements about municipality taxes, examining petitions submitted for tax amnesty or for tax discounts, making relevant decisions, carrying out auctions and contracts for lump-sum taxes, discussing official letters sent by the guilds concerned with lawsuits against tradesmen, deciding the share that would fall to each municipality in contracts that involved more than one municipality, and examining the monthly revenues and expenditures.

The Cemiyyet-i Umûmiyye-i Belediyye, which was made a significant part of the structure of Istanbul’s municipality by the 1868 Municipality Law, but which could not be realized, was reorganized with the Dersadet Municipality Code. Although it maintained its position in this new structure, some changes were made concerning its function and the method of selecting members. In this context, it was stipulated to be created from 63 members, including the şehremini, the heads of the district municipalities, two members selected from each council of the Şehremaneti and the district municipal councils. Unlike the regulation of 1868, there were seats reserved for the members selected from the Şehremaneti.

The task of providing coordination between the municipalities, as well as the task of developing the municipality model, was given to the Cemiyet; this was an important suggestion for the administering of services that exceeded the limits and capacity of one municipality in a city the size of Istanbul. If one considers that the structures developed in Istanbul would act as a model for the municipalities throughout the country, the significance of the Cemiyet can be better understood.

Despite all this, it was not until the declaration of the second Meşrutiyet (constitutional monarchy) that the first meeting of the Cemiyet could be held. The inability to establish a healthy municipality structure and the problems experienced in applications after the Dersaadet Municipality Code, much like the period between 1868 and 1877, prevented the convening of the Cemiyet, most of whose members came from the district municipal councils. As the Cemiyet could not be convened, its functions were assumed by the Şûra-yı Devlet, for the most part.27

|

Table 2-The District Municipalities to be Established in Istanbul in 1877 |

|||

|

District 1 |

Sultanahmet |

District 11 |

Tarabya |

|

District 2 |

Beyazıt |

District 12 |

Büyükdere |

|

District 3 |

Samatya |

District 13 |

Beykoz |

|

District 4 |

Fatih |

District 14 |

Anadoluhisarı |

|

District 5 |

Eyüp |

District 15 |

Beylerbeyi |

|

District 6 |

Beyoğlu |

District 16 |

Yenimahalle |

|

District 7 |

Hasköy |

District 17 |

Doğancılar |

|

District 8 |

Beşiktaş |

District 18 |

Kadıköyü |

|

District 9 |

Arnavutköy |

District 19 |

Adalar |

|

District 10 |

Yeniköy |

District 20 |

Makriköy |

The district municipalities, which began with Beyoğlu, made progress with the establishment of five municipalities. However, the fourteen district municipalities that were set out in the 1868 municipality law could not be realized. Six municipalities had been established in Istanbul and run with difficulty; now twenty district municipalities were to be established, as stipulated by the 1877 Dersaadet Municipality Code. The establishment of this structure was based on the administrative structure of Paris. However, the branches in Paris that had administrative characteristics were transformed into independent district municipalities in Istanbul, each having legal entities separate from the Şehremaneti.

Not only was the number of district municipalities increased to twenty, the Dersaadet Municipality Code also reorganized their limits. In the city center it was stipulated that municipalities that had a smaller area, but which were denser in population be established. On the other hand, even though Beykoz, Kadıköy, Ayestafanos and Büyükdere were among the largest districts of Istanbul, they had a relatively smaller and more dispersed population. The inadequacy of the means of transportation and socio-economic differences in Istanbul enabled the acceptance of smaller municipalities. In this way, it was aimed to strengthen the service capacity of municipalities. Some changes were made in the names of the district municipalities. While the names, Ayasofya, Aksaray, Kasımpaşa, Mirgun (Emirgan) and Üsküdar were abolished, Sultanahmet, Beyazıt, Samatya, Hasköy, Arnavudköy, Anadoluhisarı, Yenimahalle, Doğancılar and Makriköy were established as new district municipalities.

With Dersaadet Municipality Code, the previous two laws regulating the Beyoğlu municipality were abolished. The Beyoğlu District Municipality, which was directly connected to the grand vizier and equipped with special means, was reduced to be equal with other municipal districts. In this way, a single legal structure was created for all Istanbul municipalities, without any differences. This regulation also aimed to put an end to the practice that only some districts benefitted from municipality services.

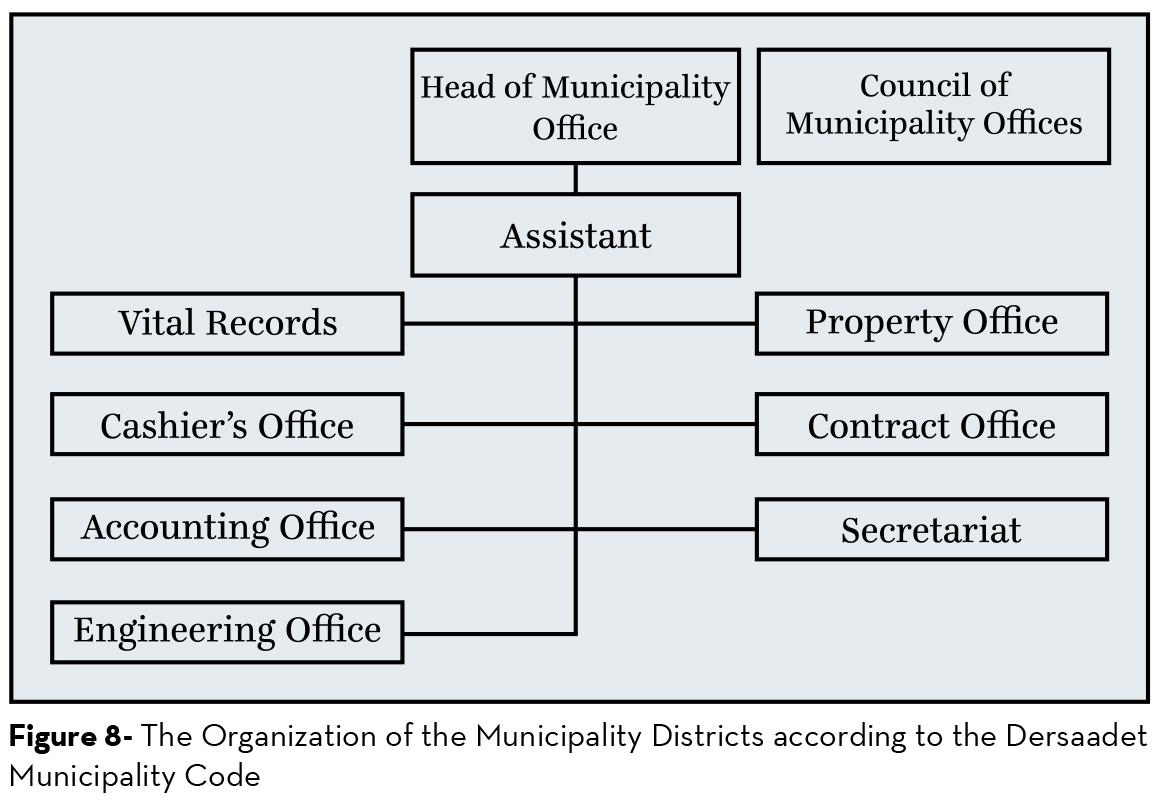

With the Dersaadet Municipality Code, the organizational structure, consisting of the head of the district municipalities and council was maintained. Although the method of appointing the head of the district municipalities continued, stipulating a new condition that the head be chosen from among the council members at least ensured that someone who had already been elected came to the office. In addition to new regulations which were introduced to ensure that the municipalities were independent legal entities, the method of election of the council members and the appointment of the head of the district municipality from among the elected members were regulations that positively affected the independence of the district municipalities.

The district council was composed of eight to twelve members, depending on the size of the district. The members of the council, who were elected through limited participation of the population, remained in office for two years. The head of the district was at the same time the head of the council. It was stipulated that half the council members were to be renewed every year. This procedure was implemented for the first council, at the beginning of the second year, by drawing lots for half of the council members; in following years new members were elected to take the place of the members who had finished their second year. The council, which was to meet every week, had to assemble with an absolute majority and made decisions with a majority vote.

The Functions of the Municipalities

In addition to the efforts to generalize modern municipality structures in Istanbul, there were also efforts to extend the scope of their services. In this context, the scope of services of the Istanbul municipalities were broadened and reorganized with greater details in the Dersaadet Municipality Code. In the Şehremaneti-district municipality model, duties were mainly given to the Şehremaneti, while a more limited functional area was given to the district municipalities, which constituted the second level. It is important that the regulations of the Dersaadet Municipality Code which were related to the responsibilities of the municipalities stayed in effect until 1930. While there were changes in the organizational structure of the Istanbul municipality during this period that lasted for almost half a century, the functional structure continued to exist.

With the Dersaadet Municipality Code, the power to confiscate, an important tool of development in the city, was given to the municipalities. Moreover, having regulations in the Code concerning the organization of the squares, one of the main public places of the city, reflects the importance given to this issue and the change in the perception of city planning. The functions related to the inspection of the construction and restoration of public buildings are similar to the functions of the Şehremaneti during the classical period.

|

Table 3- The Duties of the Municipalities according to the Dersaadet Municipality Code |

|

During this period when trams, the Tünel, and domestic sea transportation were operated by the private sector, based on a method of concessions, the process of granting such concessions was in the hands of the central administration. This was why the task of ensuring the substructure as well as those related to transportation was given to the municipalities. In respect to providing water for the city, there was a system that shared authority with the Ministry of Waqf. This was why the dual structure of the municipalities and the Ministry of Awqaf continued during this period.

One of the important regulations introduced by the Dersaadet Municipality Code consisted of the rules that strengthened the legal entities of the municipalities. Giving the municipalities the right to defend themselves in court, the right to go to court and the right to manage their revenue-generating properties were regulations that demonstrated their legal entity. Moreover, not transferring the revenues that had been collected to the central treasury, but rather being able to spend these funds on matters related to the municipality was a regulation that strengthened their independence.

An Interim Solution for the Municipality Model

In order to establish the twenty district municipalities that were stipulated by Dersaadet Municipality Code, first the members of the district municipal councils needed to be elected. As a first step, İntihab Encümenleri (Election Commissions) were formed. However, due to the Russo-Turkish War, a large number of migrants were coming from the Balkans to Istanbul, and this changed the situation. The election councils were put in charge of the migrants’ board and accommodation. Upon the change in the functions of the commissions, even if temporarily, the election of the members of the council, and therefore the establishment of the municipalities, was postponed.

Although the elections were postponed, the preparations by the commission formed within the Şehremaneti to establish the municipalities continued. Works were carried out concerned with organizational structure and the personnel of the new district municipalities. Even though twenty district municipalities had been set out in the Dersaadet Municipality Code, the reports of the commission demonstrated that such a large number of individual municipalities would require a large budget. In reaction to this, the organizational structure of the municipalities and the personnel tables were reexamined and attempts were made to reduce the financial burden.

In Istanbul, where there was no provincial administration, the task of police work was left to the Ministry of Gendarmerie. Other tasks related to provincial administration were carried out by the Şehremaneti. The sub-provinces (sanjaks) of Biga, İzmit and Çatalca and the district (kaza) of Kordon were connected to the Şehremaneti. At the center of the Şehremaneti was a structure consisting of a council that was responsible for tasks related to the municipality; there was another council that was responsible for civil tasks and various other offices. As the existence of two councils was causing confusion and unnecessary expenditure, the Şehremaneti was in favor of uniting them. Şûra-yı Devlet decided to unite the two councils until a time when the new vilayet kanunu (Provincial Law) was in effect, and thus the budget was significantly reduced.

The delay in the establishment of the district municipalities caused problems in local services in many parts of the city, and this caused people to complain. In order to find ways to solve the problems of Istanbul’s municipality, in 1877 a commission was formed. The members of the council were Yusuf Rıza Pasha from the Şehremaneti, Black Bey, head of Altıncı Dâire-i Belediye (the sixth district municipality,) Halil Râmi and Şerif Ali Efendi. The commission that worked for two years on the matter of the municipalities in Istanbul did not achieve any tangible success.28

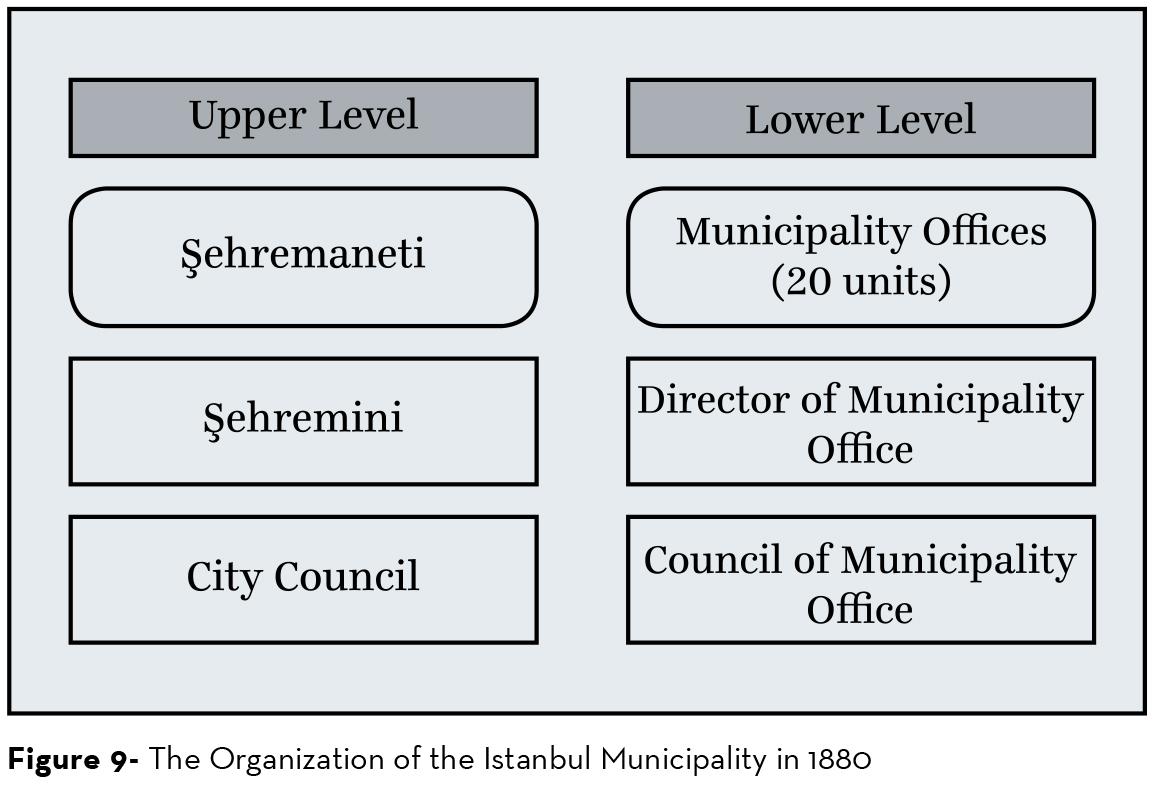

By 1880, the developments experienced during the process of approving the Şehremaneti’s budget led to the emergence of a new municipal structure in Istanbul. The collection of a variety of property tax, based on different regions, was suggested for the new municipalities. The collection of property tax in the thirteen districts of Istanbul was carried out by the central treasury. Some districts were united and the number was reduced to ten; a decision was then made to establish district municipalities in the same regions. This proposal, which was approved by Şûra-yı Devlet went into effect by an imperial edict dated May 29, 1880. The financial saving that was to be achieved by establishing ten municipalities instead of the twenty that were stipulated in the Dersaadet Municipality Code was the main reason for this new structure.29

In this new structure that was formed by reorganizing the twenty municipalities that were set out in the Dersaadet Municipality Code into ten municipalities, there were imbalances among the districts in respect to the sizes of their population. Districts such as Beyoğlu and Beyazıt, which were in the center, had the largest population. And districts like Fatih, Cerrahpaşa and Üsküdar, which constituted secondary centers, had population sizes parallel to their locations. The municipality districts on the coast of the Bosphorus had smaller populations.

The structure that was established in Istanbul in 1880, formed from the Şehremaneti and ten district municipalities, was different from that as set out in the Dersaadet Municipality Code. Not only was the number of district municipalities reduced, the formation of the Cemiyet-i Umumiye-i Belediye was postponed. During the crisis that emerged after the Russo-Turkish War the government chose a model that could function under the circumstances of the day and which would be less of a financial burden.

The members of the district municipal councils were not to be elected, nor were the head of the councils to be selected from elected members. A new structure was developed; here the head of the district municipality and other personnel were to be appointed by the sultan and all were included in the general budget of the government. Parallel to the functions given to municipalities by the Dersaadet Municipality Code, limited units and staff, rather than a structure based on expertise, were formed.

|

Table 4- The Districts of the Municipality and the Population in 1885 |

||||||

|

Municipality Districts |

Male |

Ratio (%) |

Female |

Ratio (%) |

Total |

Ratio (%) |

|

1. Beyazıt |

84.882 |

16,7 |

67.081 |

18,4 |

151.933 |

17,5 |

|

2. Fatih |

64.021 |

12,6 |

50.524 |

13,9 |

114.545 |

13,2 |

|

3. Cerrahpaşa |

63.541 |

12,5 |

59.496 |

16,3 |

123.037 |

14,2 |

|

4. Beşiktaş |

39.935 |

7,8 |

30.672 |

8,4 |

70.607 |

8,1 |

|

5. Yeniköy |

7.497 |

1,5 |

6.353 |

1,7 |

13.850 |

1,6 |

|

6. Beyoğlu |

156.905 |

30,8 |

80.388 |

22,0 |

231.293 |

26,7 |

|

7. Büyükdere |

8.694 |

1,7 |

5.951 |

1,6 |

14.645 |

1,7 |

|

8. Kanlıca |

16.070 |

3,2 |

13.088 |

3,6 |

29.158 |

3,4 |

|

9. Üsküdar |

53.212 |

10,5 |

42.455 |

11,6 |

95.667 |

11,0 |

|

10. Kadıköy |

14.053 |

2,8 |

8.743 |

2,4 |

22.796 |

2,6 |

|

Total |

508.810 |

100,0 |

364.751 |

100,0 |

867.531 |

100,0 |

Source: Cem Behar, Osmanlı İmparatorluğu ve Türkiye’nin Nüfusu 1500-1927, Ankara 1996, p. 75.

On the contrary to the set-out goals, the temporary municipality model of Istanbul, which consisted of ten district municipalities and the Şehremaneti, functioned for 28 years, until 1908. From the point of municipalities, it is possible to describe the period of the First Meşrutiyet as a period when important legal regulations were introduced, but one in which the implementation did not reach the same level, with only a limited development being made. Despite all structural changes and problems experienced by the district municipalities, they were able to expand their legitimacy basis as the main administrative unit.

The Administration of Istanbul during the Second Constitutional Period

The process that began after the declaration of the Second Meşrutiyet meant a new period, not only for the central government, but also for the municipalities in Istanbul. The attempts to reopen Meclis-i Mebusan, which had been closed after the Russo-Turkish War and could not be opened during the subsequent 30 years, provided an opportunity for the application of a belated model for Istanbul municipalities.

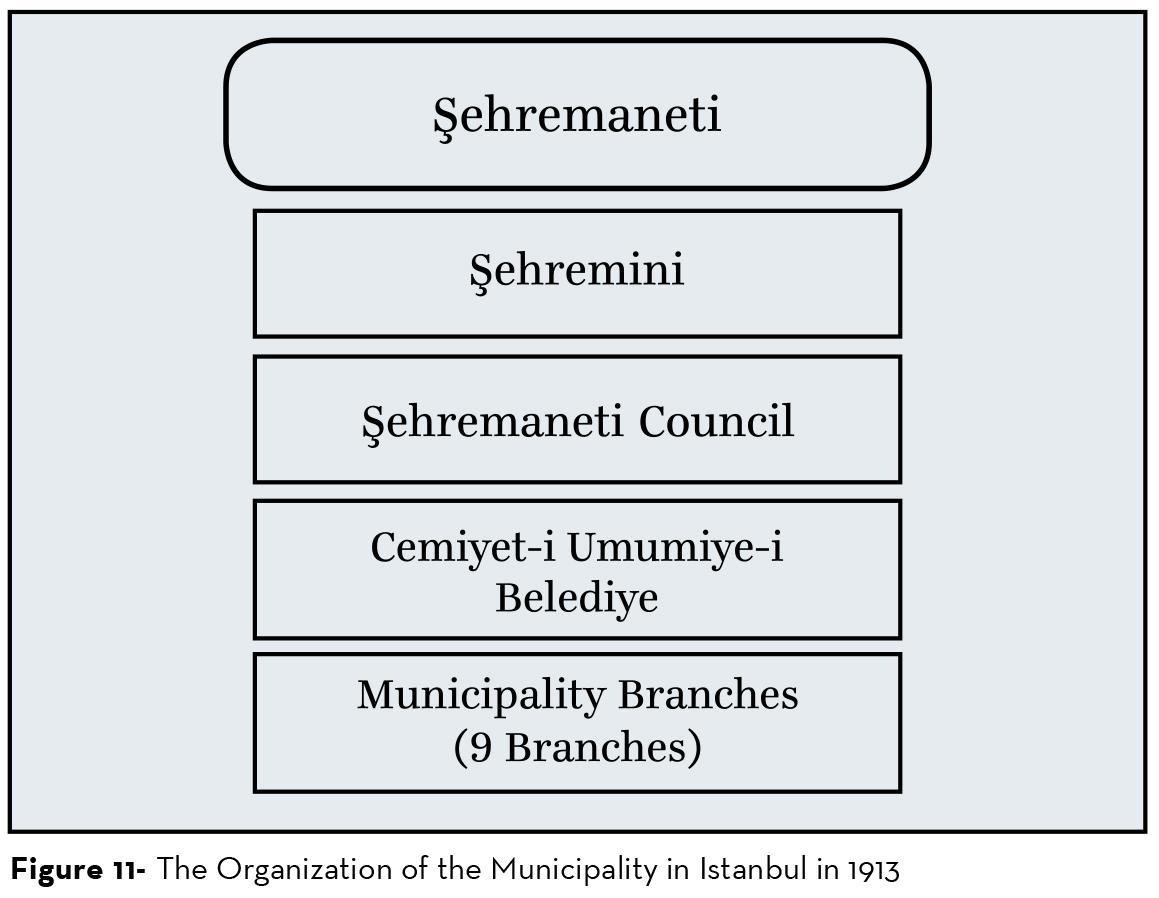

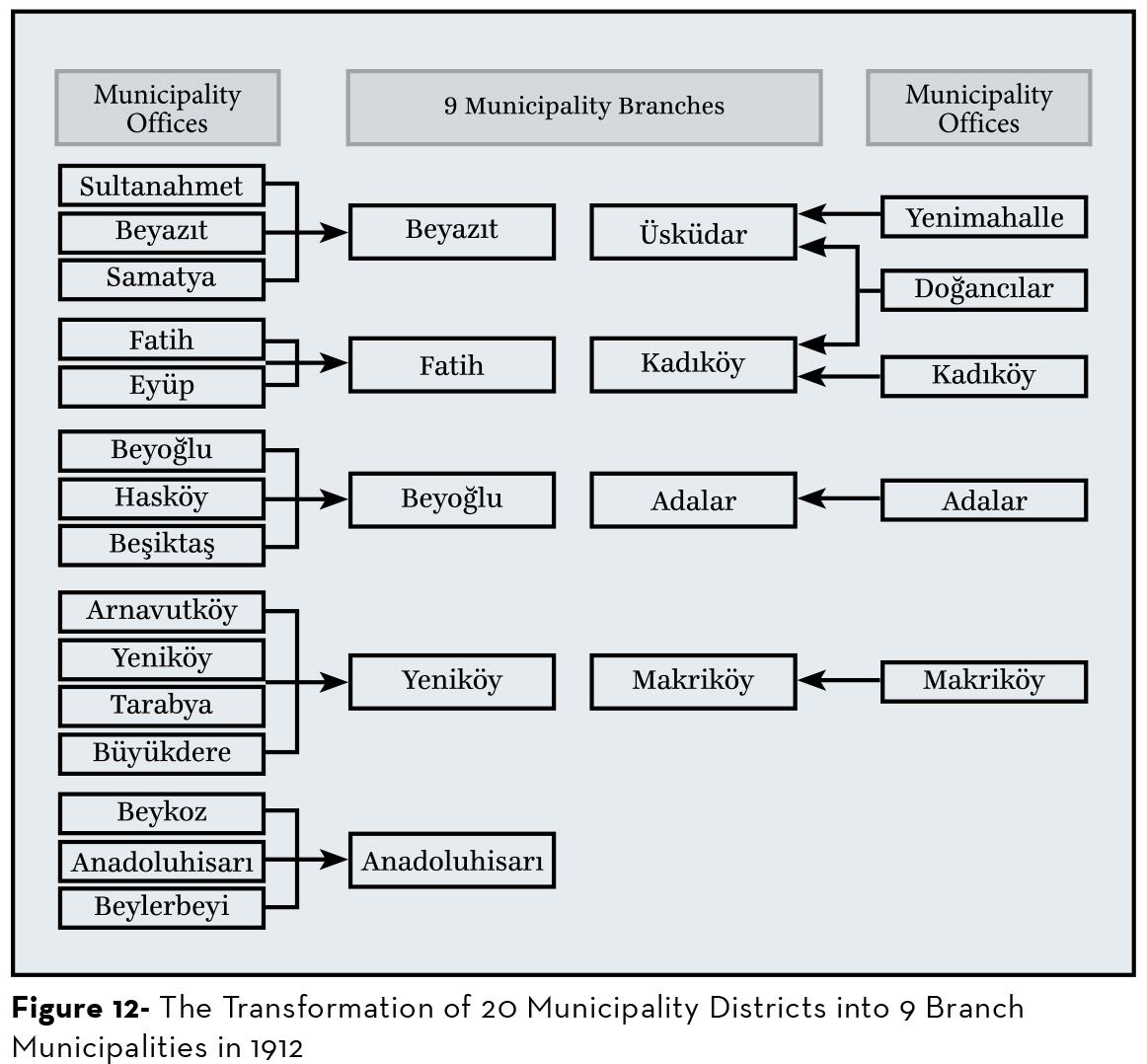

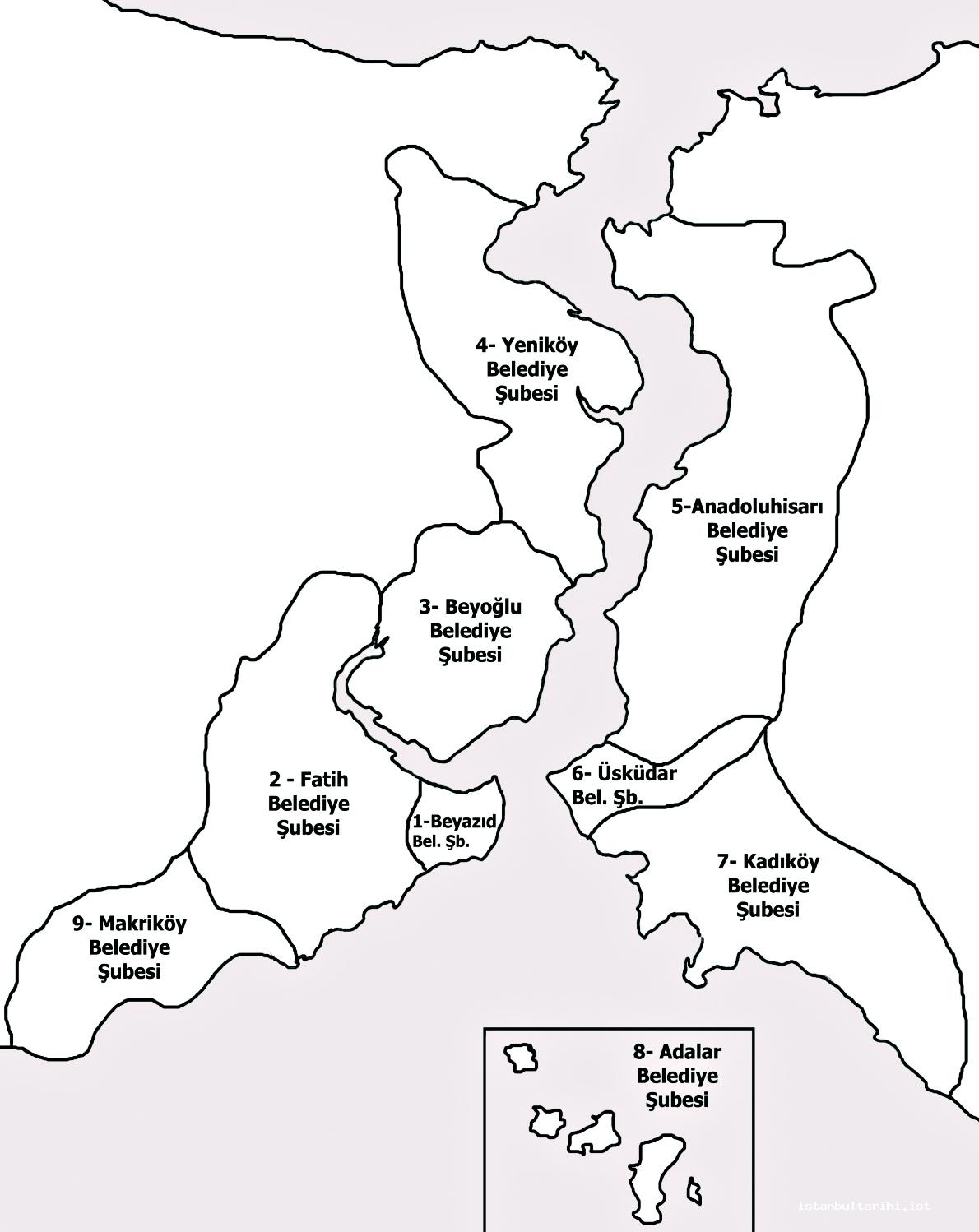

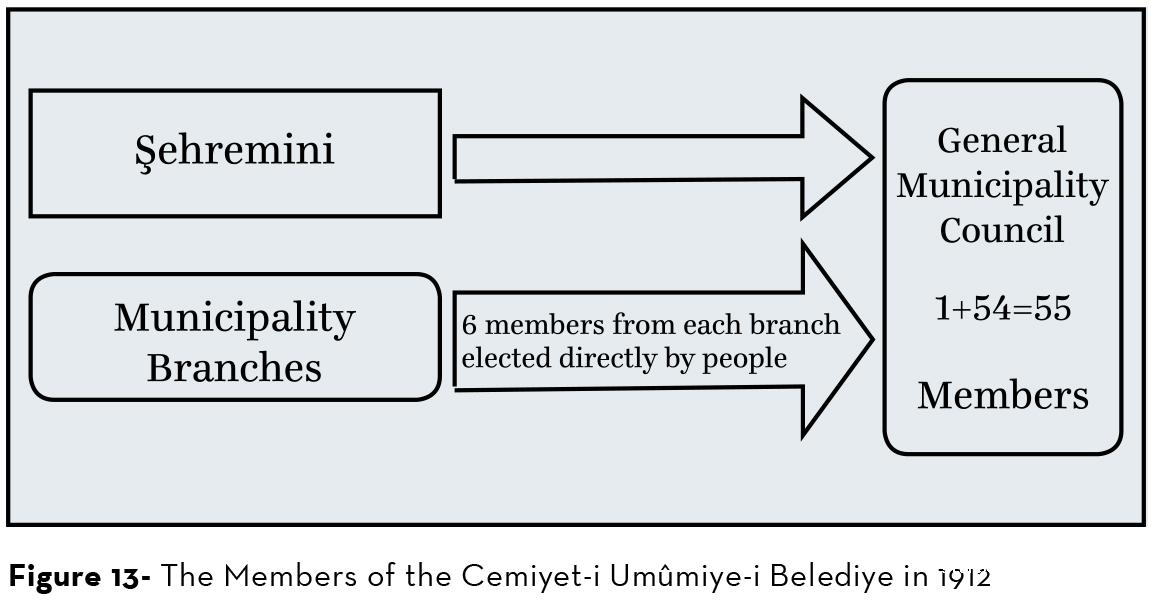

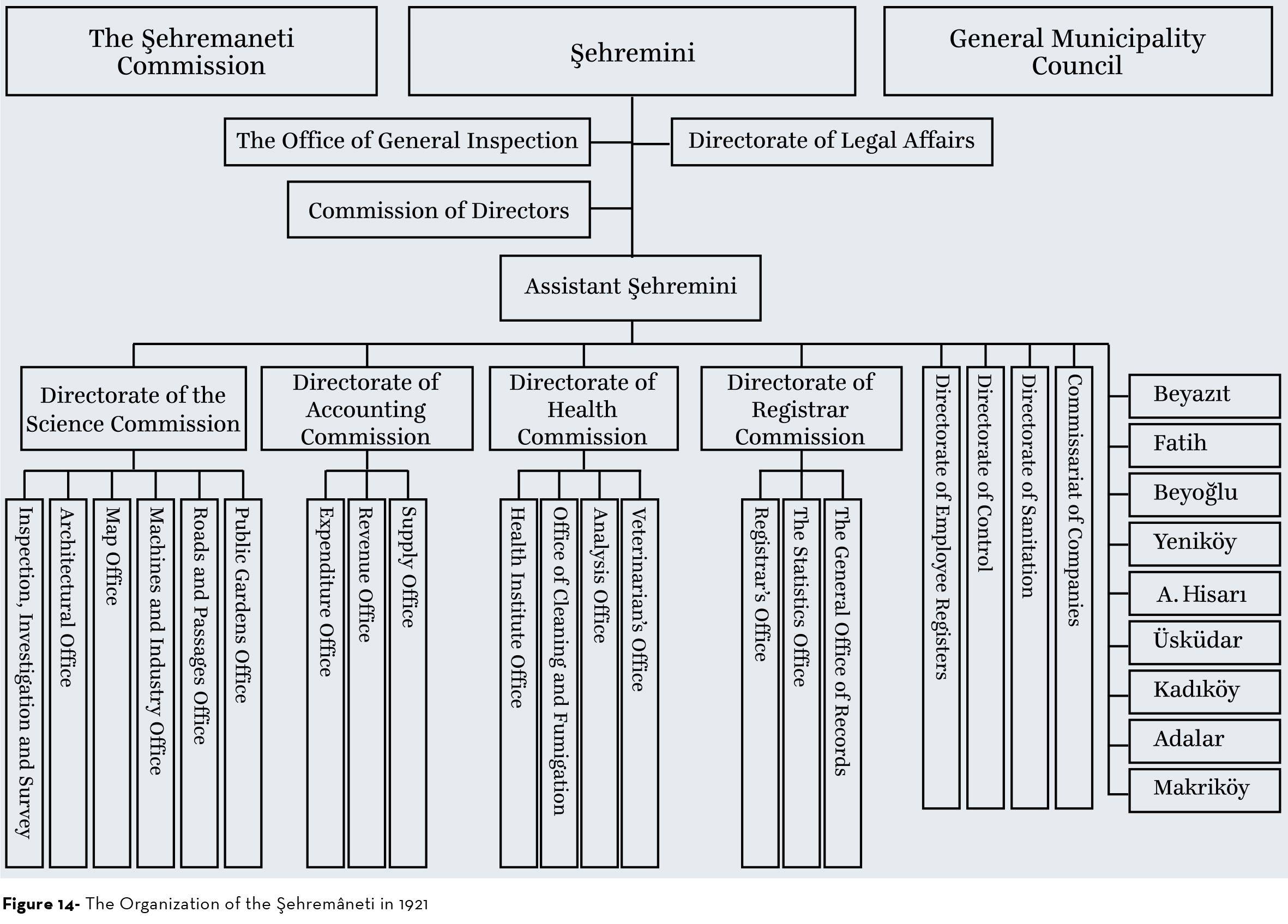

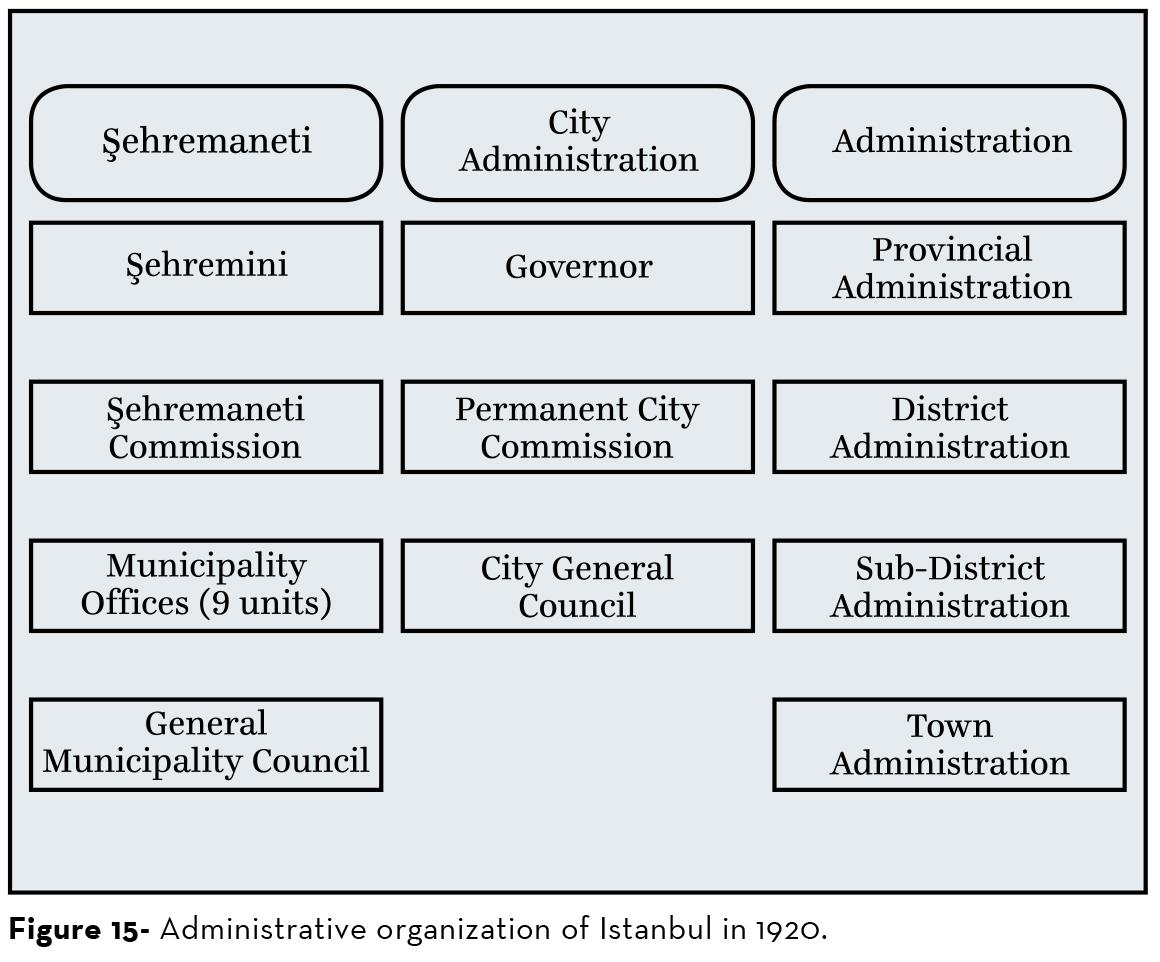

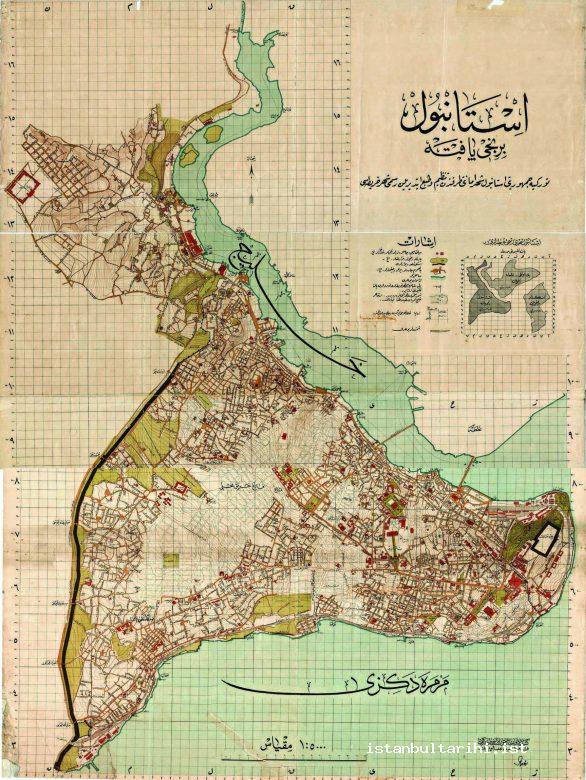

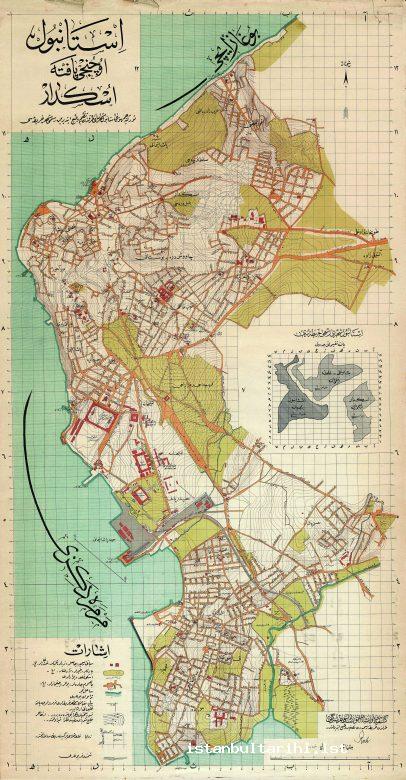

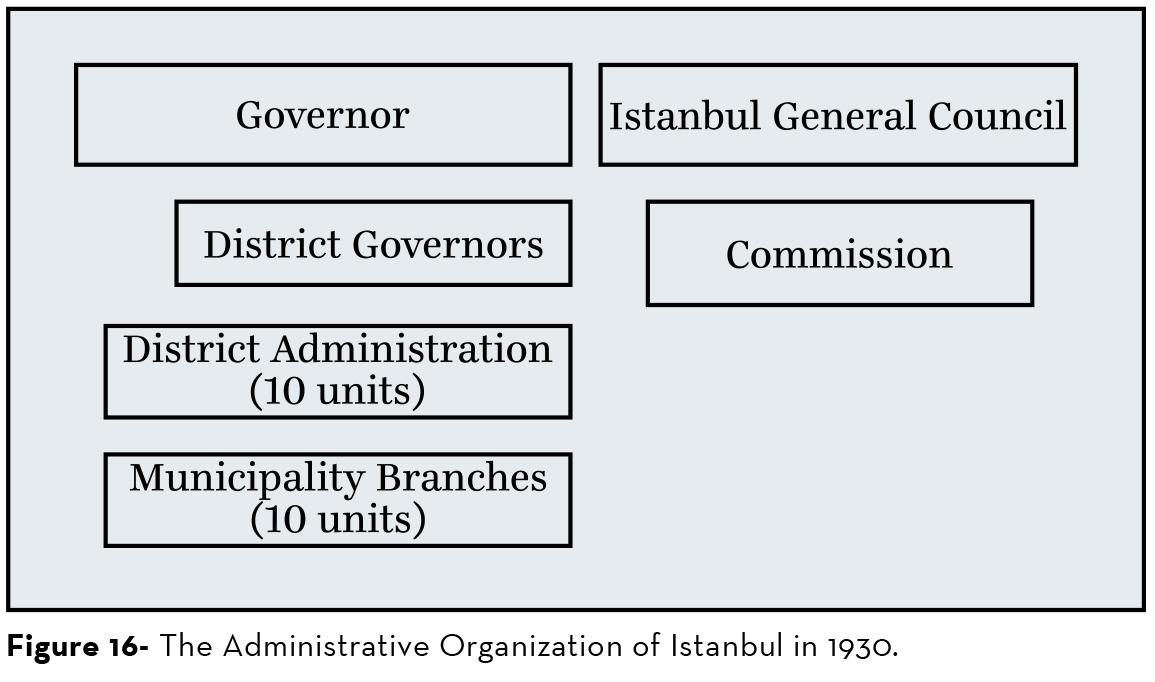

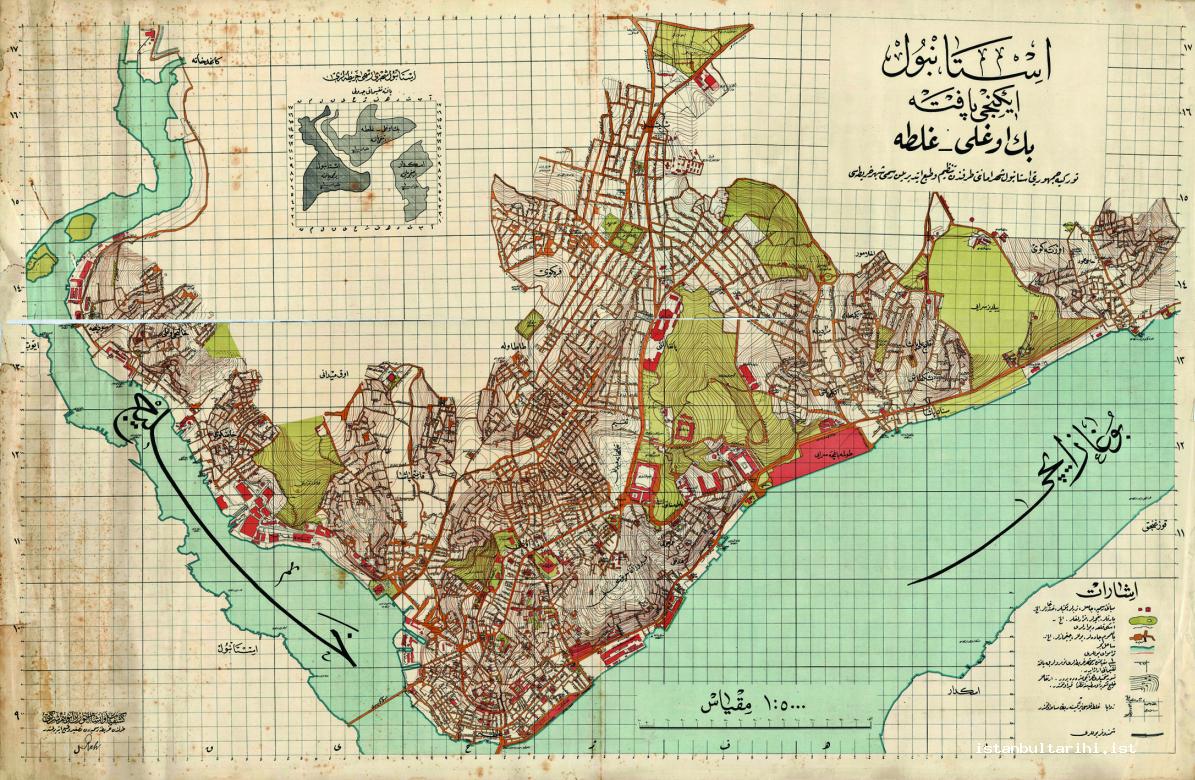

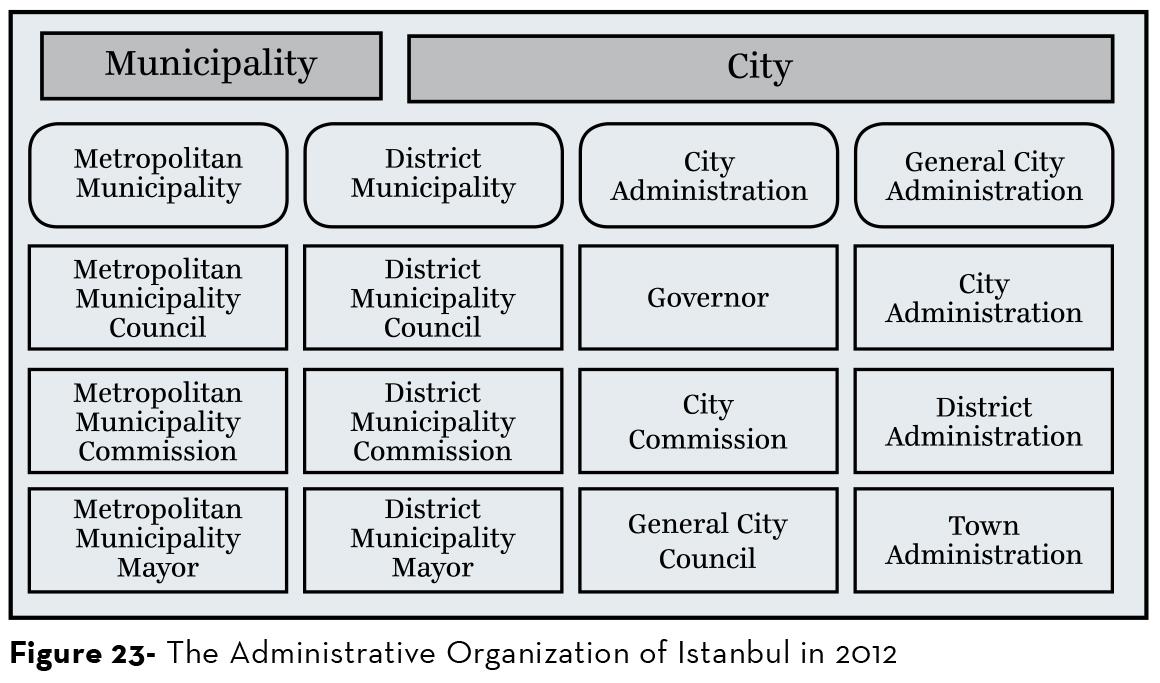

In order to elect the deputies in keeping with İntihab-ı Mebusan Kanunu (the Code for the Election of the Deputies,)30 all twenty municipalities had to be established in Istanbul. Not only had each municipality been designated as an electoral district, the municipal councils were also to assume the function of elective boards. In this context, it was necessary to establish the twenty district councils as stipulated in the Dersaadet Municipality Code and then to carry out parliamentary elections. In a letter sent to ten district municipalities by the Şehremaneti on August 25, 1908, the municipalities were informed that the existing organizations were to be abolished, twenty municipalities were to be established, and the mayors would be determined by election.31