THE CONCEPT OF ENTERTAINMENT IN BYZANTIUM

Entertainment was one of the most fundamental aspects of daily life in the Byzantine era. The Byzantine public was entertained by numerous sacred or secular holidays, festivals and ceremonies. Residents of the empire’s capital city, Byzantium, enjoyed watching chariot races, plays and religious processions in the Hippodrome. The carnival Apokreas, in which residents attended torchlight processions in disguise, was very popular. During the Nea Selene (new moon) phase residents would often celebrate by lighting fires and jumping over them. City taverns would be packed with people eating and drinking wine in great amount while listening to music. The holidays, celebrated only once a year in the provinces, began as religious festivals, but eventually turn into fairs in which magicians (magoi), astrologers and illusionists would participate, in spite of objections from the church. In some cases, the church tried to prevent modes of entertainment that they deemed inappropriate by applying restrictions on performers or banning them outright, but these efforts would not often deter the Byzantines.

One of the era’s most essential forms of entertainment were the shows held at the Hippodrome. While all major cities contained hippodromes, the most spectacular was that in the capital. As a venue for shows and spectacles, the hippodromes also provided important social areas for the general public. On offer to Byzantine audiences were a wide variety of shows: horse races, trained animal performances, gladiator competitions similar to those which took place in Ancient Rome, and less violent spectacles as well. In addition to these, the Hippodrome also held sacred ceremonies, public celebrations and political debates. In such cases, the Hippodrome would become the proverbial heart of the city. Theatrical performances were often subject to censorship or restricted due to the fact that actors could criticize the Church. While pantomime performers would put on improvisational plays, acrobats and musicians would transform the major cities into fairs.

It was traditional for aristocratic circles to organize lavish feasts (symposion), hunting parties, sports tournament such as tzostra and tzykanion. At the same time, it was traditional for the common public to watch various street performances: animal shows performed by the Romany population, using dogs, monkeys bears, snakes, elephants, camels, rhinos, and other exotic beasts, acrobatic demonstrations, magicians and dancers; the Byzantine public were also familiar with puppet shows. The public also would enjoy themselves at the taverns where they consumed alcoholic beverages and danced. Large-scale and important religious festivals were an excuse to organize fairs. Quite often, sheds and carefully-prepared tents would be erected for these fairs in open spaces close to religious structures, thus giving them a religious and commercial significance. The most famous fairs were those in Trebizond (Trabzon), Khonai (Honaz)1 in the Phrygia Pacatiana region, and the Demetria in Thessaloniki.

WORLDLY ENTERTAINMENT IN BYZANTIUM

Festivals Inherited from Ancient Rome (Romaikai Giortai)

The most famous holidays were the Borta, Byrtae, Broumalia, Mayoumas, Rozalia or Rouzalia, and the ‘anniversary of the city’. The Bota Publica was a pagan festival, which had been celebrated on January 3 since 44 BC in Rome; during this festival the participants would pray for the state’s welfare and the emperor’s longevity. This was an exuberant festival during which many races would be organized, animals were sacrificed and feasts were held; it was cancelled by an order of the emperors Arcadius and Honorius. This festival, which would take place at the Hippodrome in Byzantium, was finally banned by the Council of Trullo (692) because people continued to sacrifice animals while they were enjoying themselves.2 Following this, the Bota holiday continued to be celebrated in Constantinople until the ninth - tenth centuries, albeit in a transformed state. Although this festival appeared in the official calendar during the reign of Emperor Konstantinos Porphyrogennetos VII and its ritual was adapted to the Christianity, it was completely forgotten by the twelfth century.3

Another holiday that was celebrated with feasts and dancing was Byrtae. According to Faidon Koukoules, an expert on Byzantine social life, some identified Byrta with the Mayoumas Festival, although the roots of the former remain unknown. Recourse to Byzantine sources reveals that this festival was banned during the reign of Emperor Anastasios.4 According to John of Antioch, this ban was enacted when the archon (chief magistrate) of the capital, Constantine, lost the public support when he continued to want to celebrate the Byrtae Festival over a period of time: “τὴν αὐτὴν ἐπιτελεῖν τῶν Βρυτῶν πανήγυριν βουλευσάμενος ὀλίγου διώλεσε τὸν ἃπαντα δῆμον”.5

In spite of its Roman roots, some thought that this festival embodied Hellenistic motifs in the twelfth century. As a matter of fact, Theodoros Balsamon stated that Broumalia and Bota were ancient Hellenistic festivals.6

Natalis Dies (the anniversary of the city) continued to be celebrated until the reign of Theodosius III (eighth century) in Constantinople. The public used to sing hymns, and would ask for permission to dance on Mese Street, which was known as the largest and most central street of the city. In the meantime, there were symposion (feasts) held at the palace for the archonts.

Carnival (Apokreas)

The Lupercalia Festival was a legacy from Ancient Rome that continued to be celebrated under the name of apokreas (carnival) in the Byzantine era. According to the Roman tradition, butchers were in charge of events during the Lupercalia Festival, which celebrated the arrival of spring. The festival aimed to clean the city by expelling evil spirits, thus unleashing health and bountiful growth. Dating back to Ancient Rome, this pastoral celebration was held between 13-15 February. On the basis of its general character and the dates of celebration, some believe that the Lupercalia Festival formed the basis of the carnivals that were later held in European countries.

The primary types of entertainment were sacred and civil ceremonies. Ceremonies arranged to exclusively celebrate an event or an anniversary in the capital Constantinople created colorful scenes on the streets of the city and filled the city with great crowds. According to the opinions of modern Byzantine experts, there was a direct connection between the apokreas and the Hippodrome. This connection was so strong that when the people’s interest in horse racers began to wane at the end of the twelfth century, the impression performances organized by Emperor Alexios Angelos III held at the Hippodrome drew the attention of the public back to this space. The emperor had the musicians of the Hippodrome brought to the Blachernai Palace on the coast of the Golden Horn to amuse the guests in the last days of the apokreas. The Makellarion Hipodromion performances were organized during the Sarakostis fasting period, held before Easter; at this time, the Hippodrome would be closed and the horse racing season was over.

Carnivals held in the centers of provinces and cities materialized in the Byzantine era as they did in European countries. These carnivals contained a number of ancient traditions, and expressed in particular a need both for entertainment and to break free from the oppressions of society. Transitions between seasons, in particular that from winter to spring, marked the union of worldly-material pleasures with metaphysical concerns. The entertainment aspect of the carnival became overpowering. The carnival was celebrated with costumes, entertainment and the giving of alms, much in the manner that Halloween is celebrated today. The conventional implication of the carnival was a period of entertainment and amusement. Held before the start of a seven-week period of fasting, in which marriage, dancing, entertainment and even the wearing of jewelry was forbidden, carnivals allowed Christians to prepare for periods of abstinence by first indulging themselves. The opening ceremonies of these Triodion (three-week carnivals) would be marked with fireworks, calls from town criers, and drums.

Early Byzantine sources mention that both male and female residents of Byzantium had taken part in carnival festivities since the fifth century; they would wander around the city clad in costumes. Sources from the same century also note that soldiers would occasionally sneak into crowds of citizens in disguise, imitating their generals and having fun. It is also clear that Byzantines continued to enjoy the carnival’s festivities in the seventh century, despite the early prohibitions, restrictions and fines issued by the Church. These sources also mention that priests attended carnival festivities wearing animal costumes in the tenth century. However, the carnival underwent a transformation, in the broadest sense of the word, in the thirteenth century. This was a time when similar carnivals were being held in European countries.

W0eddings (Gamoi)

Weddings were one of the most important occasions in Byzantine social life. Over time, wedding ceremonies gradually embraced the customs of the Church, with marriage being institutionalized. As a result, the Church was able to ban relationships other than marriage. As an institution, marriage came to be identified with special ceremonies, and thus became a traditional institution. Traditions, such as putting a garland on the heads of the newlyweds, exchanging rings and placing belts decorated with pins, hoops, and figures on the bride, became essential parts of these occasions. Byzantine laws and traditions banned subjects from consanguineous marriages, marrying heretics, Jews, or those from different social classes. The pairing of bride and groom was typically made by the parents, and particularly the fathers, of those who were to be married. A woman from the outside would play an intermediary role in these marriages. In exchange, she would receive twenty percent of the dowry and pre-nuptial presents. This was, in a way, a financial insurance that the marriage would last. If the woman filed for divorce, she would lose all the property that she had brought to the marriage, or a percentage of her dowry equivalent to this value.

Weddings in the Byzantine Empire were typically celebrated for more than a week, with certain weddings lasting up to thirty or forty days. Imperial weddings were special cause to celebrate, with great amounts of wine and plenty of musical performances. The groom often ordered feasts to be arranged throughout the entire empire.7 The expenses of these feasts, which were open to the public, were met by the imperial treasury. The thirteenth-century writer Georgios Akropolites revealed the splendor of an imperial wedding in his account of the wedding between Emperor Isaac Angelos (1185-1195) and a Hungarian princess. According to historians of the Byzantine era, large numbers of animals were sent to the capital from the provinces and from nearby Bulgaria; these were distributed to be butchered for the feasts.8 This must have been a sight worth seeing.

Byzantine historians also state that a number of residents who had gold and silver goods in their house got caught up in the excitement of this wedding and displayed their wealth during the celebrations. Protocol demanded that the emperor made donations of gold and silver to the Church, the nobility and the people.9 At these times, the emperor would pardon prisoners10 and promote those who were waiting advancement.11

Among the commonest instruments played in Byzantine celebrations were the kithara, the flute and the panflute. Members of the public would typically wear garlands on their heads.12 Many theaters would be set up in central parts of the city; here comedians and magicians would perform while the public watched. In certain theaters it would be common for performers to tease and mock their audiences. The Church, meanwhile, regarded wedding celebrations as a continuation of pagan traditions, that is, an invention of Satan, and thus objected to these celebrations. The Church wanted to impose religious beliefs on the Byzantines traditions and rituals, which were predominated by simplicity. The Church believed that wedding celebrations were sacred rituals, and this should be emphasized. They imposed the idea that marriage should be pursued with caution and modesty, and that it must be equipped with simplicity and good manners.13

It was normal for events and entertainment to be organized in the Hippodrome to mark imperial weddings. Apart from the highly popular horse races, the Hippodrome also played host to spectacles in which exotic animals and birds were put on display. Exhibitions of tightrope walking and other performances in the Hippodrome caused excitement among the general public.14 Emperor Theodosius II (b. 401- d. 450) followed the traditions of the day and ordered not only horse races, but also theatrical performances to honor his marriage to the Athenian Eudocia in 415.15

However, there were also solemn wedding celebrations abiding by the regulations of the church. Theophylact Simocatta described the wedding ceremony of Emperor Maurice, which took place at the end of sixth century, in these words: “Garlands were placed on the heads of the emperor and the empress, and like everybody else who follows this most sacred and true belief they delved into the mystery of Jesus, both from the divine and mortal aspect.”16

PLACES OF LEISURE AND ENTERTAINMENT IN THE BYZANTINE EMPIRE

Strict laws and regulations influenced Byzantine communal living; in general, such rules did not encourage entertainment. Texts written by priests urged the people to lead a life in keeping with Christianity. According to this doctrine, Christians should not be inclined to dance or take part in theatrical performances if such undertakings seemed not to be in keeping with Christianity. However, such suggestions and prohibitions, which appeared frequently in Byzantine texts, suggest that the people did not comply. Despite the fact that such strict pious regulations and rules appeared, as well as constant warnings to comply with the same, it would not be accurate to think that the residents of Constantinople obeyed. Sacred holidays, anniversaries and important government occasions presented appropriate opportunities for entertainment.

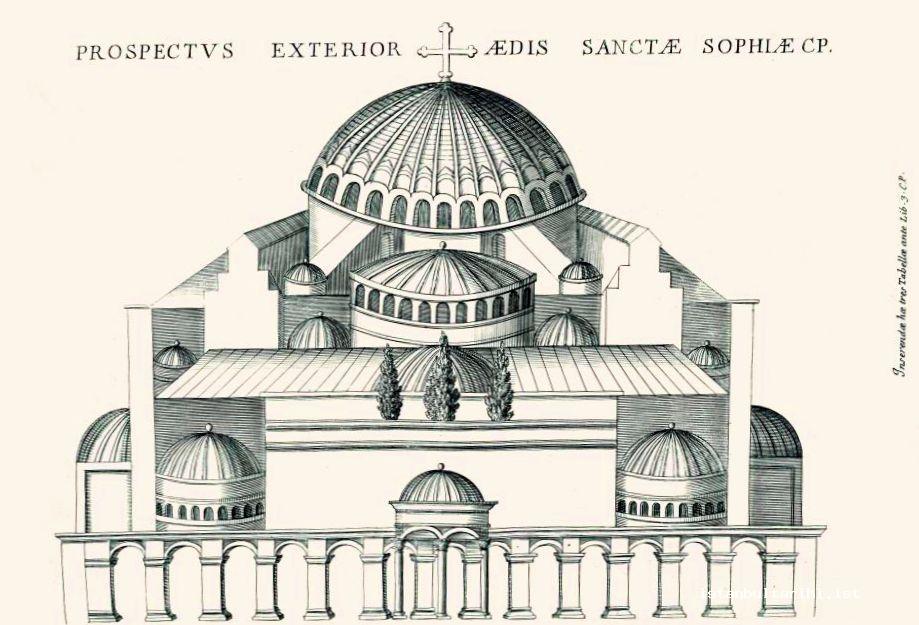

Between 324-330 Emperor Constantine the Great, the founder of Constantinople, adorned and invigorated his new capital city with wonderful artefacts brought from all over the empire. While Rome was built on the basis of suitable architecture and pagan traditions, Constantinople was designed as a Christian city to house the most sacred and important palace. The buildings within the palace, which were surrounded by decorated fountains, mosaic roads, works of art, and gardens with rare plants and trees, as well as the Hippodrome building, which extended from the palace’s inner courtyards, were the most important venues for socializing in the Byzantine capital. The Circus Maximus was taken into consideration before the Hippodrome was built; upon completion, the Hippodrome acted as a natural extension of the palace’s facilities. This spectacular building grew to become the heart of the city, and a few times a year massive crowds would sit on the Hippodrome’s marble stairs and watch entertaining spectacles; these included horse races, chariot racing (Hippodromies) and other shows. Not only the public, but also the emperor and his retinue would attend horse races here. The permission and approval of the palace was necessary for these races to be held. They would take place on special occasions and bring great joy to the city; occasionally races were held in honor of visiting foreign leaders or ambassadorial representatives.

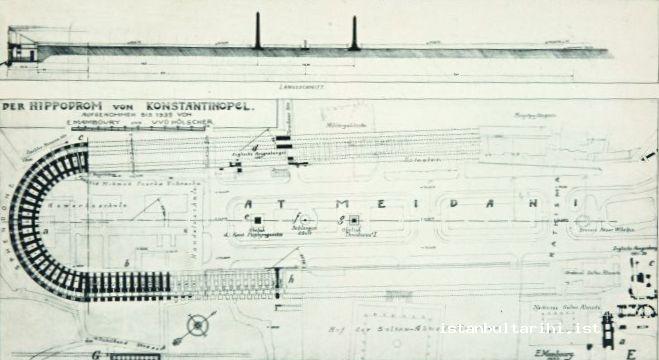

The Hippodrome (Ippodromos)

The word ἱππόδρομον, which means “horse path” in Greek, is still used today. The building’s construction began during the reign of Septimius Severus (193-211), one of the late Roman emperors, but was finished during the reign of Constantine II. As the grandest structure of its type, the Hippodrome could seat a large audience, which would sit in the massive stands, running up and down the structure. The Hippodrome’s field was divided into two sections by a wall known as the spina. During races, officials would move sculptures to indicate the number of laps completed by competitors. The overall size of the venue was 120 meters in width and 480 meters in length, allowing for up to ten chariots to compete at once. The stands were split into forty level stands and could hold 100,000 spectators. During hot weather, the Hippodrome would be covered with awnings called velum, put in place with the help of hundreds of pulleys. Stables for horses and changing rooms for competitors and performers were located beneath the stands.

The Emperor himself would often be present to watch the races with his entourage and family; they would sit in a box called the kathisma. The residents of the capital would be seated in the part reserved for the demos. The kathisma had a special enclosed section, in which only the emperor would sit; this area had an exit directly to the palace, which was designed to keep the emperor safe if the crowd got out of hand.

The Hippodrome was the center of social and political life in Constantinople. The venue was the site where official announcements about succession to the throne were made, and was also frequently used for state visits. In the wake of riots, prisoners would be displayed in the Hippodrome. Similarly, the Hippodrome was the venue of religious executions, and also celebrations of military triumph. Audiences at these events would cheer to express their support, and jeer to communicate their discontent. The Hippodrome was also an open-air public speaking venue in which the public announced their requests and expectations from the government. There would be frequent bouts of verbal sparring between the passionate spectators of competing teams. Emperors would often discover the needs, wants, hopes and desires of the public via this type of expression in the Hippodrome.

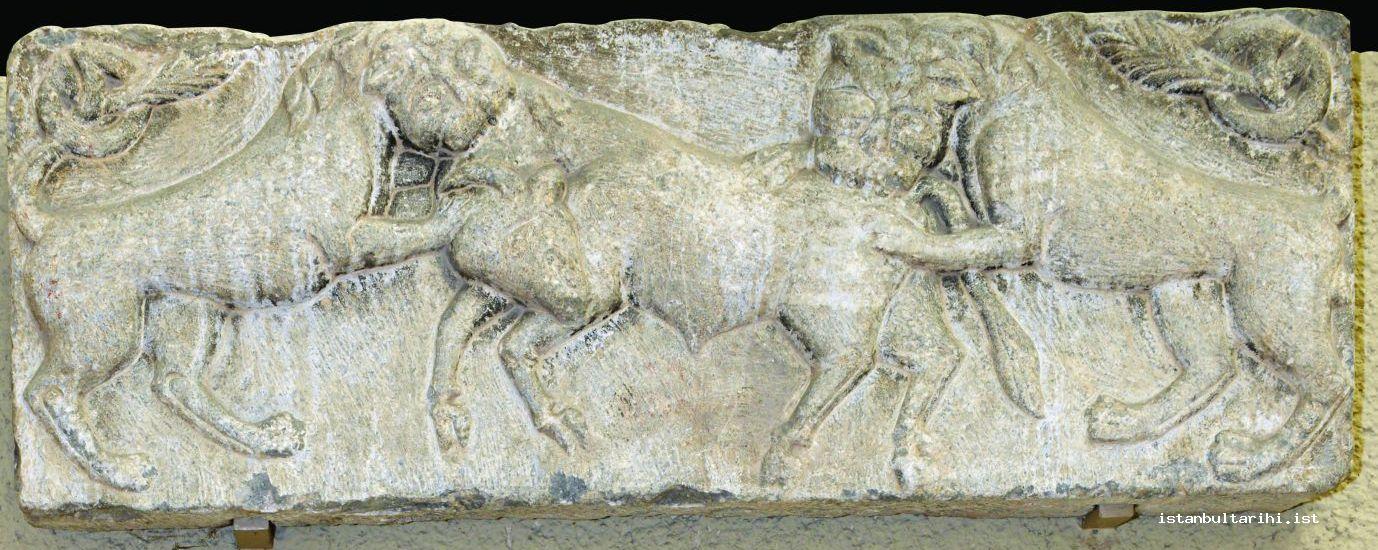

The chariot races, or the hippicon (τὸ ἱππικὸν), were the most popular activities in the Hippodrome. Despite the fact that these activities would usually take place on predetermined dates according to the calendar, they would also be held to honor military victories, the birthdays of the emperor and his family and official state visits. Additionally, chariot races were sometimes organized in order to get people ignore the failed military expeditions. In addition to the most important holidays, including religious festivals such as Cristougenna (Noel), Theophania and Easter, as well as Hagioi Apostoloi, chariot races did take place on Sundays. These races were subjected to objections from the clergy, as they drew people away from church. Despite this opposition, the Byzantines were the most passionate supporters of chariot races.

The Orthodox Church clergy cited the fact that the Byzantine cities would be packed with competitors and supporters on race days. According to Christopher of Mytilene, citizens who could not make it to the Hippodrome would often ask the results of the races from their friends who attended.17 Those who could not gain entrance to the Hippodrome would climb nearby buildings to watch the races from the balconies and terraces which had views of the Hippodrome. No matter their vantage points, spectators would typically watch the racing chariots, shouting, swearing and quarreling with the opposing team’s supporters; they would get into fights and place large bets on these races.

The demos were responsible in large part for organizing the social aspects of the races; the residents of the capital were divided into four demos. Each demos enthusiastically supported a certain team. These teams were the representatives of the demos, and were clad in clothing of different color material, woven with golden or silver thread. The color divisions were as follows: Blues (οι Βένετοι: Venetoi), Greens (oı Πράσινοι: Prasinoi), Reds (οι Ρουσσοι: Russoi) and Whites (οι Λευκοι: Leukoi). The Blues and Greens were the most powerful teams. Apart from having their own color, each demos also had its own emblem. The seating plan was organized so that the supporters of the Blues and Greens would be seated facing each other. The Blues were seated at the carceres, while the Greens could be found at the spendon, the arc-shaped part of the Hippodrome.

The long time that these teams continued to exist reflects the power of tradition in Byzantine society. While the primary teams were the Whites and the Reds, these two were soon joined by first the Blues and then the Greens, eventually forming a four-team rivalry during the reign of Augustus (BC 31 - AD 14).18

The respective colors of these teams represented the earth (green), air (white), fire (red) and water (blue).19 However, with the addition of the Purples (porphyry) and the Golden (dore) teams during the reign of Emperor Domitian (b.51 – d.96), the symbolic meanings of the teams became lost.20 Soon after, the least successful teams were incorporated into more successful ones; as such, the Reds joined the Greens, and the Whites joined the Blues, affiliations that made both teams stronger. These unifications had such strong implications that the races held during the early and middle ages in the Byzantine Empire were typically between the Greens and the Blues.

While the Greens were situated around Chalcedon (Kadıköy) and Hagia Euphemia Church, the Blues were located on the other side of the Bosphorus, close to the Blachernai Palace (Ayvansaray). Given these circumstances, competition between the two was more than just athletic, and the rivalry often amounted to political and religious opposition as well. In the event of a threat to the city, however, the teams would typically unite to form a unified military force; this sort of defense, for instance, was very effective during the Gothic invasion around Adrianople (Edirne) in 378, and actively defended Byzantine land during battles with the Avars. Increases in the number of supporters at times like these demonstrated that the Byzantines could rise to the occasion and prove themselves in the event of military threat. Sources tell an insightful story about the Byzantines and their obsession with chariot racing. According to this story, during the reign of the Emperor Justinian I (527-565) a certain Antiokhos resisted pressure to sell his property, which was located close to Hagia Sophia. The emperor’s deputy dutifully imprisoned him on the eve of races held at the Hippodrome as punishment. Not wanting to miss the spectacle, the poor man eventually agreed to sell his property.

Chariot racers in the Byzantine era were the equivalent of modern-day football stars, and they often had a great number of passionate supporters who followed them with devotion. The Hippodrome, however, was not a venue unique to the Byzantine capital; there were hippodromes in other large cities. One of the well-known Byzantine priests, the church father John Chrysostom (347 - 407), complained: “If you were to ask someone the number of Jesus’s apostles, do not expect an answer. But this man would know everything about the racers and their horses at the Hippodrome.” In another work, Chrysostom also states the following:21

They would complain and get bored if we were to go into details in church. They would say that they are aching and feel tired. However, even if there were heavy rains, or strong winds, or if it was boiling hot not, for an hour or two hours, but for most of the day, they would stay there at the Hippodrome. The elderly people have no shame in spite of their white hair, and how ridiculous they look as they run faster than the young just to attend the races held at the Hippodrome.22

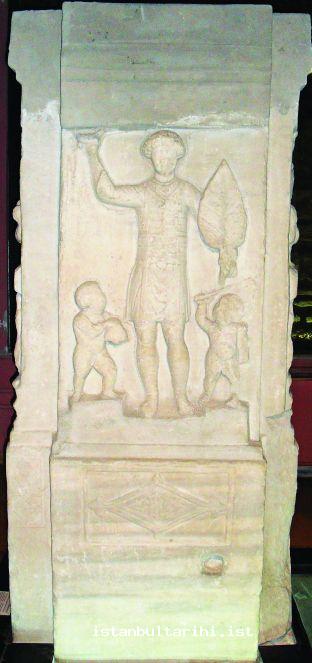

Although the general public considered the chariot racers to be stars, the authorities did not regard them as dignified citizens. This was a stance taken by the Byzantine government since Ancient Rome. In Ancient Rome, slaves were known as the heroes of the circus. The display of busts and sculptures that supported such an attitude towards slaves was subsequently banned from the Hippodrome and areas open to the public (unless they were displayed in the background).

In the early Byzantine era, the organizers of the Hippodrome races were known as the hypatos; this was a time in which Roman traditions of urban living were adhered to, up until the sixth century. In later years the emperors themselves took on this role. In chariot races, the winning charioteer was awarded a palm leaf known as the baion, which also lent its name to a race which consisted of seven laps. Race winners were also given silver crowns, as well clothing and money. When the empire was in financial difficulty, victors would have to give their crown to the winner of the next race. A representative of the emperor, known as the aktouarios (ἀκτουάριος), would present this crown to the champions. The personal crowning of the champion by the emperor was a great, though rare, honor.

The start of games in the Hippodrome would be announced by the hanging of pennants on the entries to the building the day before. The games would sometimes last throughout the entire day, but on other occasions events would finish before noon. Races typically featured chariots in which a single rider would command a team of four horses. The placement of the riders and their horses, clad in their team colors, was decided by drawing lots before the races began. A device known as a kylistra was used for the drawing of lots. During the races, chariots were required to complete seven laps around the Hippodrome’s track, turning at the dangerous spots at the ends of the spina named the meta. A normal race consisted of seven laps around the spina. At these points, competitors had to exhibit their racing skills and talent; the rider had to have great control of both his own movements and that of his horses. It was important for the driver to adjust the speed of the horses in order to successfully navigate the racetrack’s curve, so that his horses would not waste or lose their momentum. Regardless of these and other obstacles, the aim was always to finish ahead of the other competitors and win the race. This great desire to win could not be curtailed among the racers, even in the event of serious accidents which put the lives of the competitors in danger. One way in which competitors sought to weaken the chances of their opponents was by knocking off the helmet of a fellow racer; to achieve this was the guarantee of the opponents failure. Likewise, capturing the helmet of the opposition could put one at a great advantage.

The Byzantines often turned to magic as a means of either achieving good fortune or avoiding failure in their quests to become victorious. To this end, they often used an assortment of amulets. Coins which featured the bust of Alexander the Great were occasionally used as amulets, as they were believed to be the most effective. We learn from hagiographic sources and from laws that are contained in the texts such as Codex Theodosianus, that the Byzantine government’s attempts to punish the use of magic with the death penalty were normally futile. The archeological material that sheds light on the government’s attempt to control magic also supports the idea that the use magic was a common practice. The figures and writings on a piece of crockery found in the sphendone of the Hippodrome suggest that magic was prevalent among the Byzantines. The most common act of sorcery in this time period was to draw the horses of one’s racing opponents on a blade with the following inscription: “Let the horses of the Greens (or the Blues, etc.) with the following names be unsuccessful, weak and powerless.” Likewise, it was believed that chancing upon a priest would bring bad luck to the racer.23 Tablets found in archaeological excavations prove that these materials were used in the belief that they place curses on one’s opponents. Despite the fact that these formidable and exciting races were favored by neither pagan nor Christian church leaders, their fanatic spectators could not be subdued.

The reason a blind eye was turned to this extreme behavior in the Byzantine public, which was normally so strictly controlled, was that the teams and the races carried out serious social responsibilities. The emperor was responsible for the protection and care of Christian citizens, and he arranged these sorts of games to enhance their entertainment and prosperity. The citizens of the capital did not only cheer in support of their team, but also for the victory of the emperor; over time, this became a ritual.

It must have been a spectacular sight to see the public divided into their respective sections (by demos), wearing their team colors, and saluting the emperor. Nika was a typical way of cheering. From time to time, such events would get out of control, and rival teams would occasionally unite to rebel against the government. The Nika Riots, which happened at the Hippodrome, provide a good example of this. The riots were started by spectators who had become irate after the execution of some team members by the government; eventually they gained the support of some nobles who had suffered under the tax policies of Justinian I in 532. This example shows how these teams had political importance.

The Hippodrome also hosted other competitions and performances apart from chariot races. These included performances, athletic shows and spectacles put on by theater companies, all of which would entertain the public during official ceremonies. Often the Hippodrome would be transformed into a venue for circus performances when there were no races. Immediately following the races, or during intermissions, the Hippodrome would be filled with pantomime, acrobatic, dance and theater performances. In particular, children took part in the dance shows. However, the pantomime, acrobatic, comedy and singing performances were typically favored over dances and theatrical plays, which tended to focus on more serious topics. The Hippodrome also held rabbit and dog races, circus performances including elephants, giraffes, bears, and tigers, equestrian vaulting, tightrope walking and wild animal fights, all of which seem to have been equally popular.

Benjamin of Tudela, a Jewish traveler who visited Constantinople during the reign of the Emperor Manuel Comnenus I (1143-1180), wrote the following:

Skillful people from all over the world would gather here to display their personal performances (acrobatics, dexterity skills, dancing numbers, comedy pantomimes). These people would bring lions, leopards, bears and feral donkeys which they had fight each other. It simply is not possible to see a sight like this anywhere else in the world.24

The hunting of wild and exotic animals was also a popular attraction held at the Hippodrome. The Emperor Justinian I had twenty lions, thirty panthers and various other wild animals brought to the city for shows held at the Hippodrome. The program also typically included exotic birds and people brought from distant countries clad in traditional clothing. Another popular type of show was martial arts spectacles. Nikephore Phokas, an emperor who had a military background, is known to have organized such a martial arts show. The crowd, nevertheless, did not respond well to this show, and many are believed to have left in states of shock. Another odd incident took place at the Hippodrome when a Turk climbed on top of an obelisk and jumped off in an attempt to fly. This was during the shows that the emperor had ordered to honor the visit of the Seljuk prince, who had come from Lycaonia (Konya). The Turkish performer attempted to fly dressed in loose garments that resembled a parachute, to which he had attached flexible branches. After waiting for a suitable wind, the man was subjected to taunts of “Fly! Fly!” from the increasingly impatient crowd. When the man did eventually jump, he fell straight to the ground.

Acrobatics, tightrope walking, equestrian vaulting and theatrical plays also amused and entertained the public. The magician Philarius, who died a wealthy man, was just one example of those who were able to make livings out of entertaining the Byzantine public. The following story involving theater actors demonstrates that the Hippodrome was a perfect venue for the emperor to reach his public. Circuses were typically free to the public, and were events in which the public would address their concerns and complaints to the government. According to the sources, a sergeant named Nicephorus seized a ship owned by a widow during the reign of Emperor Teophilus. In spite of her repeated attempts to claim the ship back, her efforts were futile. Lacking alternatives, the widow resorted to a plan involving some actors who performed at the Hippodrome. The actors placed a miniature ship on top of a wheelbarrow and then presented it to the emperor. With the encouragement of a fellow actor, one of the main actors attempted to swallow the ship, only for the former to declare with rage: “The palace official managed to swallow the whole ship, why can you not do the same?” Theophilus thus discovered Nicephorus’s crime, and duly punished him for it.

Athletic events were also held at the Hippodrome; referred to as Greco-Roman in modern day society. These sorts of events had been held since Ancient Greece and Rome and were very popular. Christian doctrines did not regard with favor the idea of taking care of one’s body for the sole purpose of athleticism. Athletic events did not, as a result, fit in with Christian principles. The church frowned upon athleticism partly due to the fact that it was done in the nude. The educational role of athleticism during the Byzantine era meant that such displays were restricted to demonstrating working skills. The sort of athleticism that was allowed by law included wrestling, boxing, pole-vaulting and discus throwing. Other branches included javelin throwing, weight lifting, archery and the shot put. This categorization also determined the type of punishment that was to be implemented if one’s rival competitor was wounded or killed.

The splendid processions that took place when the Byzantine army was victorious in battle included officers, statesmen, soldiers and slaves walking on streets carpeted with flowers; these events, as well, were a type of entertainment that would bring Byzantines together. Spectators of such processions, whether in the imperial box alongside the emperor and his high officials, or in the stands with the general public, would celebrate with great excitement. Such passion, although criticized by some Byzantine authors, was widespread throughout society.

Sporting events that were open to the public called for athletes who were independent citizens. Slaves were only allowed to attend special events that were not open to the public. The Byzantines regarded those who participated in these games for the sake of money, such as gladiators and wild animal fighters, as dishonorable people. The athletes, in particular, were strictly controlled before the games took place; they were required to follow strict diets and were expected to stay away from women. Among the other games was included the akontismos; in this sport, a short spear and an arrow were used, as well as sticks like walking sticks; the aim was to trip up one’s opponent. A poem by Amphilochius of Iconium contained critical statements regarding the theater performances and circuses that were held at the Hippodrome. He especially found the circus dangerous, as it often divided the city into distinct social camps and encouraged citizens to riot and fight.25

The Fourth Crusade (1204) brought with it great changes, resulting in the adoption of new ceremonies by the Byzantines. Knights who came to the city from Western Europe during the fifty-year reign of the Latin Empire brought some of these ceremonies with them. As the central social sphere of the Byzantine capital, the Hippodrome witnessed many bloody tournaments organized by the city’s Western conquerors at this time.

At the same time, among the tournaments diadoratismos (διαδορατισμός) stood out. More commonly known as kontaromachia (κονταρομαχία), kontarochtipima (κονταροχτύπημα) or tzostra (τζόστρα), this was a challenging game in which mounted armor men displayed their skills in jousting and fighting. It was the most popular form of entertainment for the Western European knights and nobles in the Middle Ages. It is to be expected that this game gained favor in Byzantine at this time due to the fact that a number of emperors and wealthy, land-owning aristocrats had risen from the military class. Diadoratismos, in which members of two opposing teams competed on trained horses, had been known since the ninth century. In the centuries that followed, these jousting tournaments spread throughout all of Western Europe, especially enjoying great popularity in France, where it was referred to as tournoi. This form of competition was also exported with great success to Italy, where it came to be known by its original Greek name, giostra. The primary aim was to strike one’s opponent with a lance held under the armpit while riding towards him at high speeds, in order to unhorse him. This tournament was typically only open to noblemen, and it often ended with one of the competitors either seriously injured or dead. Erotokritos26 and similar epic and romantic tales provide rich details and information about this type of tournament.

In Europe, these tournaments were organized for the last time in Turin in 1839. John Cantacuzenus wrote about the Western nobles who organized the tournaments that took place in the Hippodrome in honor of Andronicus III Palaiologus, one of the Byzantine emperors from the fourteenth century, who was also the husband of Anna of Savoy. The historian explained that this type of entertainment was known as coustria or ternementa, and also recorded that the Byzantines learned the sport from France, Germany and Burgundy.27

Chikanion (tzykanion) was a form of polo that was adapted from the Sassanid-Persian Empire (τζυκάνιον, from the Persian tshu-kan); like Diadoratismos, this sport was performed on horses. It was typically played in a stadium known as a tzykanisterion, which was generally located in the vicinity of a great palace. It is generally accepted that the Byzantium stadium was built just southeast of the imperial palace during the reign of Emperor Theodosius II (408-450). According to John Cinnamus, the goal of cikanion was for teams to win points by hitting a leather ball (the size of an apple) through their opponent’s goal with long sticks that had nets fastened to their ends.28 This game proved to be very popular among Byzantine aristocrats, and was said to have been brought from Persian lands. Cikanion came to the Byzantine Empire during the reign of the Emperor Theodosius, and it is said to have been introduced by the Turks. Emperor Theodosios had a stadium called either cikanisterion or spherodromio built for the sole purpose of housing cikanion competitions, which grew to become a popular meeting point for the Byzantine nobility. The game reached its peak during the rule of the founder of the Macedonian Dynasty, Emperor Basil I (867-886). This is why the emperor had the old stadium knocked down, and had the Nea Ecclesia (New Church) built on a site farther east. The Nea Ecclesia was built larger and had two galleries connected directly to it. The Trebizond emperor, John I (1235-1238), in fact died after suffering a fatal blow while playing this game. The game tzykanion was played in many of the empire’s largest cities, including Sparta, Ephesus, Athens, Trebizond, and, of course, Byzantium.

Market Place (Agora)

Agoras and harbors were very important centers of social life. Shops and squares were often meeting points for those who lived in the city. Almost all of the houses in the city were situated facing the Bosphorus, the Marmara Sea (Propontis), or the Golden Horn (Khrysokeras). One of the largest agoras was located in the center of Mese Avenue, a thoroughfare that connected the city from one end to the other; this market was named after the city’s founder.

There were other agoras that were smaller in comparison, including those named after Emperor Theodosius and Emperor Arcadius. There were many colonnaded stoas and hundreds of shops where Byzantine citizens used to shop. Mansions belonging to wealthy families were also located around the markets. Apart from these permanent markets, there were many others located outside of the city. Some of these markets would be held on specific days of the week in different neighborhoods located throughout the city. Producers and various guild members would sell their products at their best prices in these markets. Such markets were not only used for shopping, but also for entertainment purposes; travelling entertainers would often come to entertain the crowds.

In addition to the annual international carnivals that were held in large cities throughout the Empire, such as those in Thessaloniki, Trebizond (Trabzon) and Ephesus (Efes), it was customary to dance, wrestle, lance, and shoot bows and arrows in the local markets. Naturally, people would also shop and drink in these markets. Despite the fact that the Church did not approve of these commercial carnivals, the state refrained from intervening, as these carnivals produced high tax revenues for the treasury.

At times like these the Romany citizens would often dance in the streets and perform feats of snake charming. Giant men, dwarves and even Siamese twins would also perform on occasion in these environments. Extraordinary performances by magicians were held in high regard and drew the attention of Byzantine shopkeepers, who were typically able to leave their shops only for a few minutes at a time. Momentous events, such as an execution of a traitor or the physical punishing of a criminal also brought crowds into the city center. Eustathius of Thessaloniki mentions that citizens would attend dances such as the syrto and antikristo (reception). Numerous kapeleia (taverns), mageireia (restaurants), and mimareia (public theaters) were typical places for entertainment, including magic and acrobatic shows. Women were forbidden from attending performances which took place in the evenings. It was also frowned upon for reputable people to attend these sorts of performances regularly. Moreover, priests and monks were not allowed inside such places of entertainment, and the women who worked in them were generally considered to be prostitutes.

During festivals, the main streets of the city would be livened up with dancing and cheering crowds who would encircle instrument players and singers. Elsewhere, others would be seated on the floor, entertaining themselves with gambling games, such as backgammon, which were banned by the Church. It appears as if priests and monks would, on occasion, play these games despite the ban. As a matter of fact, in the fourth century Eusebius of Caesarea explained that while “everyone took their own time when the preacher called for service,” “if they were to hear an instrument playing they would rush in its direction like they possessed wings.” The public particularly loved to watch female dancers as they swung their long hair. During festivals there were various shows, in many cities, that lasted from the morning until the evening. Performances by illusionists (displaying dexterity), tightrope walkers, acrobats, musicians and singers, trained monkeys, dogs and dancing bears were among the most popular.

The following information was provided by John Malalas, a 6th century historian:

One year an Italian brought a yellow dog, capable of great tricks, to the city. While its owner was standing in the markets, many people from all over the world would either give him money or jewelry, which he would then bury underground. The man would command the dog to find what he had just buried and give it back. And the dog did this! He would then ask the dog to perform many other similar tricks, and the dog would oblige! And then many began to claim that this dog had the soul of the Delphoi.29

Byzantine Taverns

It is difficult to attempt to describe the taverns in which both Byzantine high society and the general public spent ample amounts of time. There is a major lack of information which could shed light on this area of study, except for a selection of written sources; from these, we might assume that Byzantine tavern culture was similar to that of the Antiquity period (particularly in Pompeii). There were two important items that characterized the taverns: the continuous benches, the cavities where wine amphoras were placed, and the cauldron, placed above a fire, in which water was continuously boiled. Boiled water was used in the taverns to dilute wine, which was necessary due to the drink’s very high alcohol content. Eparchikon Biblion, one of the most important sources of Byzantine history from the early tenth century, states that fires burning below city shops needed to be put out at the day’s end, otherwise customers would continue to drink all night long.30 Libanius of Antioch, who lived in the third century, corroborates the popularity of these taverns: “The emptied glasses at the taverns were uncountable, both sec and diluted alcoholic drinks were consumed excessively and even those who could not manage to hold their liquor acted as if they were the lord of the drink, and they took pride in it.” Despite everything, the public’s perception of the taverns and pubs were very different.31 In every era of the thousand year long empire, drinkers and clients could always be found to make sure that this occupation continued.

FOOTNOTES

1 For Chonai, see: K. Belke and N. Mersich, Phrygien und Pisidien, Tabula Imperii Bizantini (TIB) 7, Wien: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1990, pp. 222-225.

2 F. Trombley, “The Council in Trullo (691-692): A Study of the Canons Relating to Paganism, Heresy and the Invasions”, Comitatus: A Journal of Medieval and Renaisance Studies, 1978, vol. 9, p. 5.

3 G.A. Rhalles and M. Potles, Sintagma (Σύνταγμα), Athens: G. Charophylakos, 1852, vol. 2, p. 450.11-15.

4 Trombley, “Trullo”, p. 5.

5 Ιωάννης Αντιοχείας, Ιστορία Χρονική, ed. Excerpta Constantini, De Ins., pp. 58-150 and FHG IV, 535-622; Rhalles and Potles, Syntagma (Σύνταγμα), vol. 2, pp. 448-449.

6 Rhalles and Potles, Syntagma(Σύνταγμα), vol. 2, p. 448.

7 Βίος Θεοφανούς (Vita Theophanus) (BHG 1794), Zwei griechische Texte über die hl. Teophano, die Gemahlin Kaisers Leo VI., Memoires de l’Academie Imperiale, edited by E. Kurtz, St. Petersburg: J. Glasounof, 1898, p. 6; Ioannes Kinnamos, Epitome Rerum ab Joanne et Alexio Comnenis Gestarum, edited by A. Meineke, Bonnae: Weberi, 1836, p. 211, line 5-13.

8 Georgii Akropolitae, Historiae, Γεωργίου Ακροπολίτου, Χρονική Συγγραφή, ed. A. Heisenberg, Stuttgart, 1878, vol. 1, p. 18, line 6-14.

9 Συμεων Μαγίστρου και Λογοθέτου (Pseudosymeon), Χρονoγραφία, Symeonis Magistri, Annales, edited by I. Bekker, Theophanes Continuatus Ioannes Cameniata, Symeon Magister, Georgius Monachus, Bonnae : E. Weber, 1838, p. 624, line 15; p. 625, line 8; Georgii Monachi, Vitae Imperatorum Recentiorum, ed. I. Bekker, Bonnae: E. Weber, 1838, p. 789, line 15; p. 790, line 16; Grammatikos, Chronographia, ed. I. Bekker, Bonn: E. Weber, 1842, p. 213, line 20; p. 214, line 2, Βἰος Θεοδώρας, Vita Sanctae Theodorae Imperatricis (BHG 1731), edited by W. Regel, Analecta Byzantinorussica, Petropoli: Lipsiae, 1891, p. 5; Kinnamos, Epitome, p. 211, line 7-13.

10 Bios Theophanes, p. 6

11 Konstantinos Porphyrogennitos, De Ceremoniis [Ekthesis], ed. I. Bekker, Bonnae: Weberi, 1829, p. 632, line 12.

12 Ζωσίμου, Ιστορία Νέα, Zosimi Historiae, ed. I. Bekker, Bonnae: Weberi, 1837, p. 5, line 3, 4.

13 Ioannes Chrysostomos, “Eis to Apostolikon Rhiton”, Patrologia Graeca, Paris: Migne, 1862, vol. 51/3, pars 1, pp. 210-212; Ioannes Chrysostomos, “Homilia 49”, Patrologia Graeca, Paris: Migne, 1862, vol. 54, p. 443.

14 Chronicon Paschale, ed. L. Dindorf, Bonnae: Impensis ed. Weberi, 1832, vol. 1, p. 578, line 13-17; Gregorobios, Αθηναις Ιστορία τής πόλεως τών Αθηνών, μετά- φρασις μετά προσθηκών ύπό Sp. Lampros, Πρακτικά τής έν Αθήναις Αρχαιολογικής Εταιρείας, 1-3, Athens 1974, pp. 72-73.

15 Ioannis Malalas Chronographia, ed. L. Dindorf, Corpus Fontium Historiae Byzantinae (CFHB), vol. 34, Bonn,: Weber, 1831, pp. 263, line 1-3, and p. 264, line 17-p. 265, line 7; Ioannes Laurentius Lydus, De Mensibus (Περὶ τῶν μηνῶν), ed. I. Bekker, book 4, chapter 30, line 30-40 (TLG). CSHB, vol. 29, Bonn : Impensis Ed. Weberi, 1837, p. 65, line 19 – p. 66, line 10.

16 Theophylactus Simocatta, Historiae, ed. D. D. Boor, Leipzig: B.G. Tevbneri, 1887, liber I, cap. 10, p. 57, line 17-19; pp. 58-59, line 17-19.

17 “Stichoi diaphoroi Christophorou anthypatou, gegonotos kritou tis Paphlagonias kai ton Armeniakon, tou Mitylinaiou)”, Die Gedichte des Christophoros Mitylenaios, edited by E. Kurtz, Leipzig: A. Neumann, 1903, pp. 56-57.

18 Konstantinos Porphyrogennitos, Ekthesis [De Ceremoniis], p. 588, line 20, p. 589, line 2, 4, 5, 11 (TLG).

19 Lydus, De Mensibus, book 4, chapter 30, line 30-40 (TLG). CSHB, vol. 29, p. 65, line 19 – p. 66, line 10.

20 Dion Cassius, Historiae Romanae (Ρωμαική Ἱστορία) (Xiphilini epitome), p. 219, line 4-5 (TLG); Byzantios Skarlatos, Κωνσταντινούπολις, s. 453.

21 Ioannes Chrysostomos, “Homilia 33”, Patrologia Graeca, Paris: Migne, 1862, vol. 59, pars 8, pp. 187-188.

22 Ioannes Chrysostomos, ‘Homilia 58’, Patrologia Graeca, Paris: Migne, 1862, vol. 59, pars 8, pp. 320-321.

23 Codex Theodosianus, ed. Th. Mommsen – P. M. Meyer, vol. I.1, I.2, II, Berolini: Weismannos, 1904-1905, p. 9.16.11.

24 The Itinerary of Benjamin of Tudela, Critical Text, Translation and Commentary, edited by Marcus N. Adler, London : Henry Frowde, 1907, p. 21.

25 Amphilochius, Bishop of Iconium, Amphilocii Iconiensis Iambi ad Seleucum, ed. Eberhard Oberg, Berlin: De Gruyter, 1969.

26 Erotokritos, Poema Erotikon, ed. Vincenzo Cornaro, Venetiis, 1835, vol. II, line 1324-2375; vol III, line 60. Ioannes Kantakuzeni Eximperatoris Historiarum, ed. L. Schopen, Bonnae: Weberi, 1828, vol. 1, p. 205, line 8-10, 13-16.

27 Ioannes Kantakuzeni Eximperatoris Historiarum, vol. 1, p. 205, line 8-10, 13-16: “Σαβοιας ουκ ολίγοι των ευπατριδων εις την Ρωμαίων αφικνούμενοι, .... κυνηγεσίων και γαρ συμμετειχον τω βασιλει, και την λεγομένην τζουστρίαν και τα τερνεμέντα αυτοί πρωτοι εδίδαξαν Ρωμαίους πρότερον περι των τοιούτων ειδότας ουδεν.”

28 Kinnamos, Epitome, p. 263, line 17; p. 264, line 11.

29 Malalas, Chronographia, p. 453, line 15; p. 454, line 4.

30 Das Eparchenbuch Leons des Weisen, ed. J. Koder, Corpus Fontium Historiae Byzantinae (CFHB), vol. 33, Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1991, p. 132, no. 19, pars. 2-4 (Περί καπήλων).

31 Libanius of Antioch, Libanii Opera: Orationes, ed. R. Forster, IV vol., Leipzig: B. G. Teubneri, 1903-1908.