As a result of an initiative taken by seven insurance companies of varying sizes in Trieste in 1833, the insurance company Lloyd Austriaco was established.1 The directors intended to collect all the up-to-date data about the situation of foreign markets, general navigation news, and all accidents at the Trieste Port; they employed agents working in important ports to carry out this task. They demanded two florins of every 1,000 florins from the total funds of other insurance companies who wanted access to this information, thirty florins a year from the traders in Trieste, and fifty florins from independent Austrian citizens.2 The Lloyd Austriaco Company quickly proved to be profitable, and after realizing its goals the company decided to enter the marine transport business, which at the time had not been sufficiently developed in Austria or Trieste. On May 28, 1855, the company communicated this intent to its shareholders and to the Austrian government.3 Consequently, Austria, which had been tardy in carving out a market for itself in the Far East and the North American continent,4 now concentrated on the Mediterranean Sea and the Ottoman State.

Karl von Bruck, a member of the board of directors,5 travelled to Vienna on October 5 1835, to explain the reasons for entering the marine transport business.6 The directors knew that it would be impossible to raise the capital of 1,000,000 florins that was needed for the business from Trieste; thus, they intended to establish a corporation and include capitalists from Viennese society in the company.7 Salomon Rothschild, who was contacted in Vienna by Marco Palenta, one of the founders of the company,8 not only supported the enterprise in Vienna, but also purchased stocks worth 300,000 florins.9 The Greek and Bavarian governments and the Egyptian governorship also purchased company shares.10

|

Table 1- Freight and Passenger Transportation by the Austrian Lloyd Steam Company in 1838 |

||||||

|

Voyage |

Total Number of Passengers |

Material Value of Freight (in Florins) |

Number of Letters |

Freight |

Small Packages |

|

|

Number of packages (parcels) |

Weight |

|||||

|

Trieste-Istanbul-Alexandria (16 voyages) |

3.331 |

2.237.361 |

44.480 |

12.926 |

19.138 |

2.577 |

|

Trieste-Istanbul (8 voyages) |

1.343 |

1.128.699 |

23.353 |

4.453 |

9.675 |

738 |

|

Istanbul-Alexandria-Thessaloniki-Trieste (10 voyages) |

538 |

110.076 |

3.112 |

1.376 |

2.596 |

174 |

|

Total |

5.212 |

3.476.138 |

71.945 |

18.755 |

31.409 |

3.489 |

Source: Giornale del Lloyd Austriaco di Notizie Marittime e Commerciali, 1839, v. 5, nr. 71, p. 3-4.

The Austrian government, whose intention was to increase its influence in eastern ports, as well as to maintain its dominance over the French in the Mediterranean and to establish a modern communication network, viewed the company in a favorable light. In the end, with the permission of Emperor Ferdinand, the company was established on April 30, 1836.11 As a consequence, based on this new development, on August 2, 1836, the company altered its bylaws, adding shipping and marine transportation to the insurance department; it was then announced that the Navigazione A Vapore dell Lloyd Austriaco had been established and that it would offer voyages to the Adriatic, the Mediterranean and the Black Sea for the public.12

The First Voyage to Istanbul and the Black Sea Route

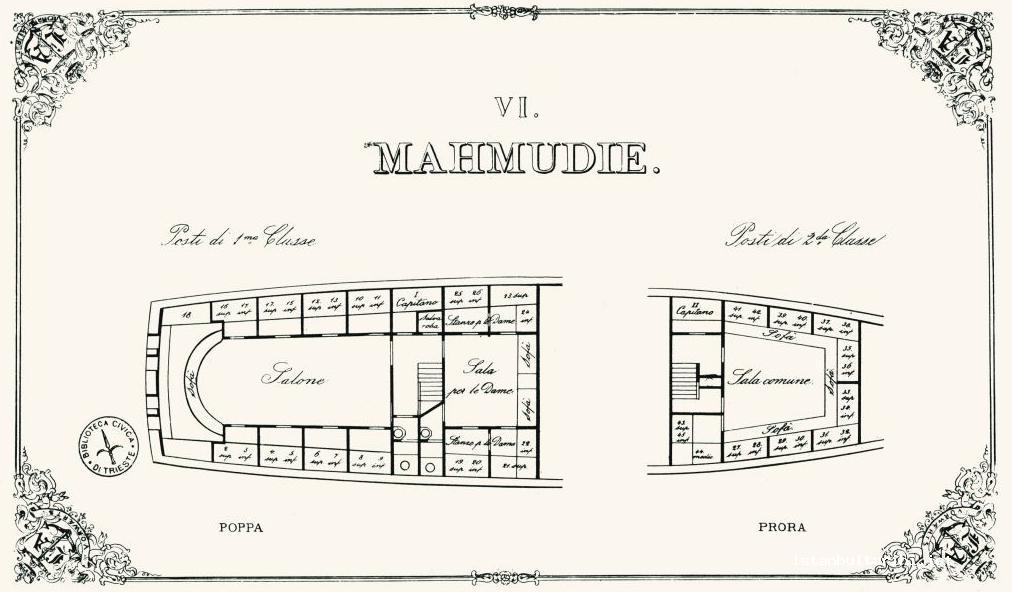

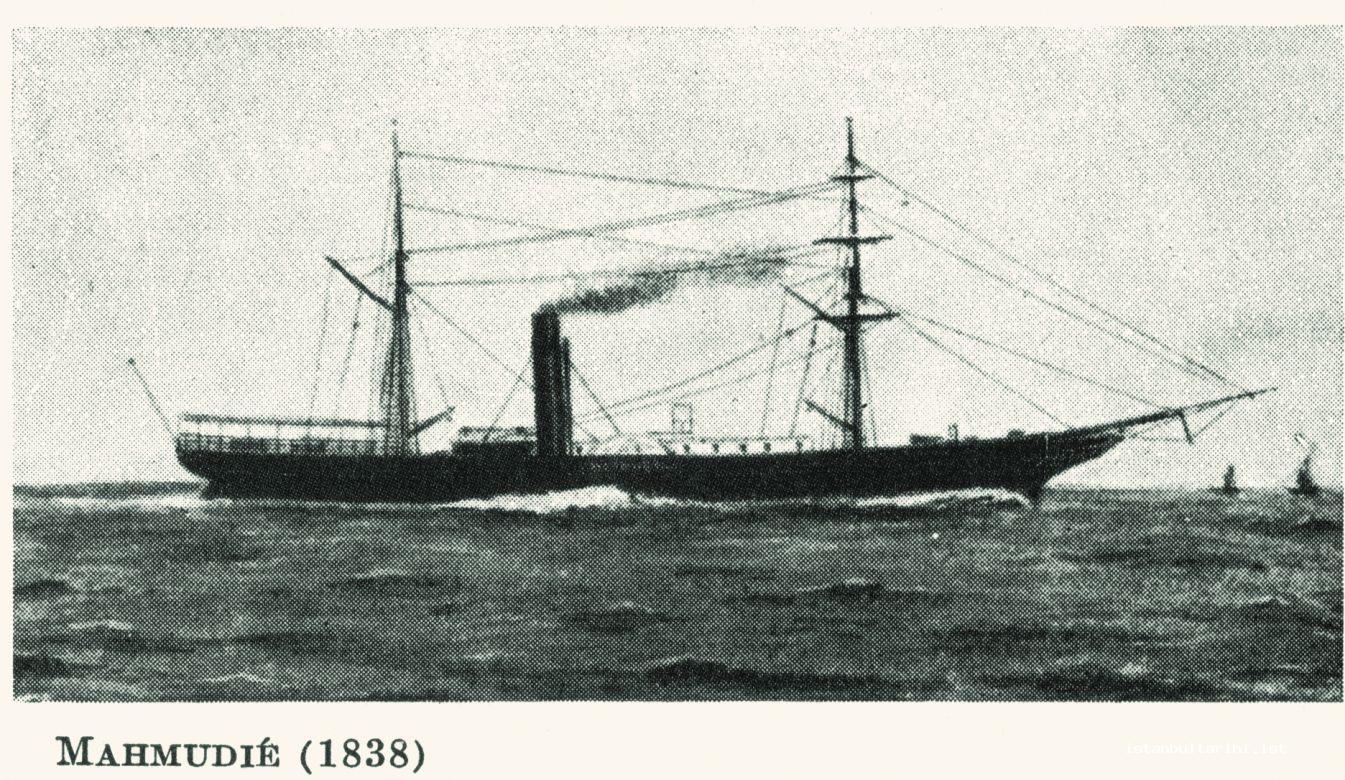

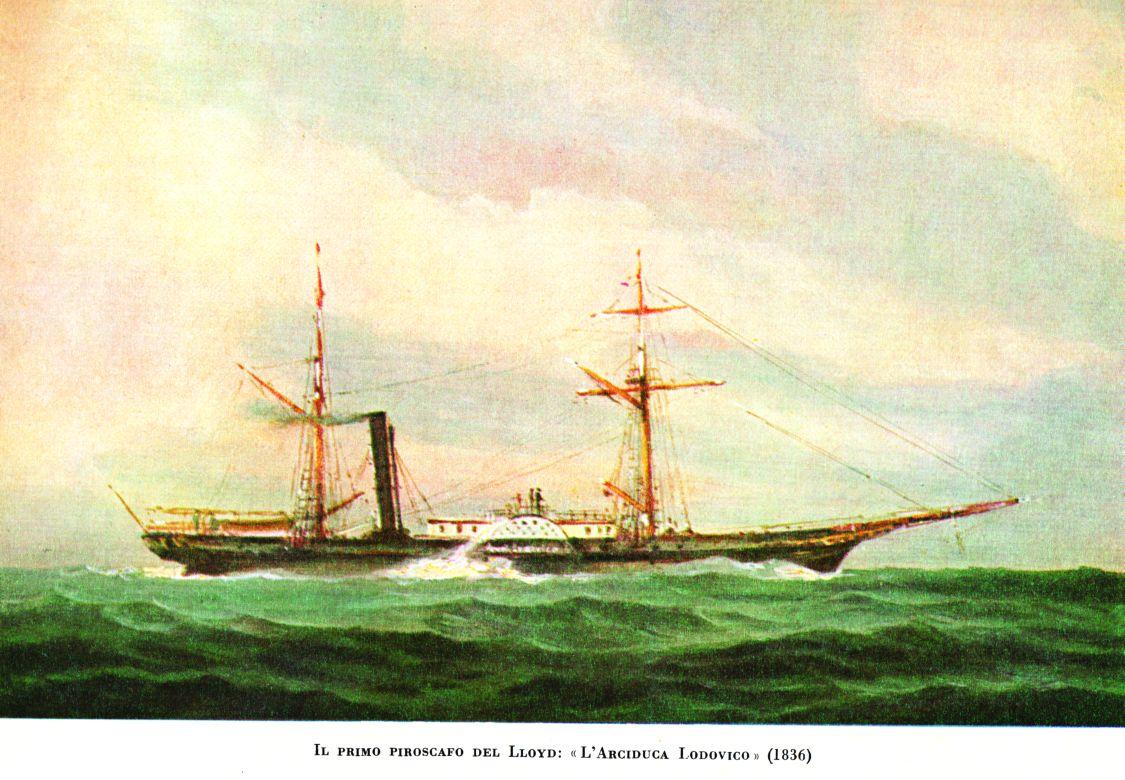

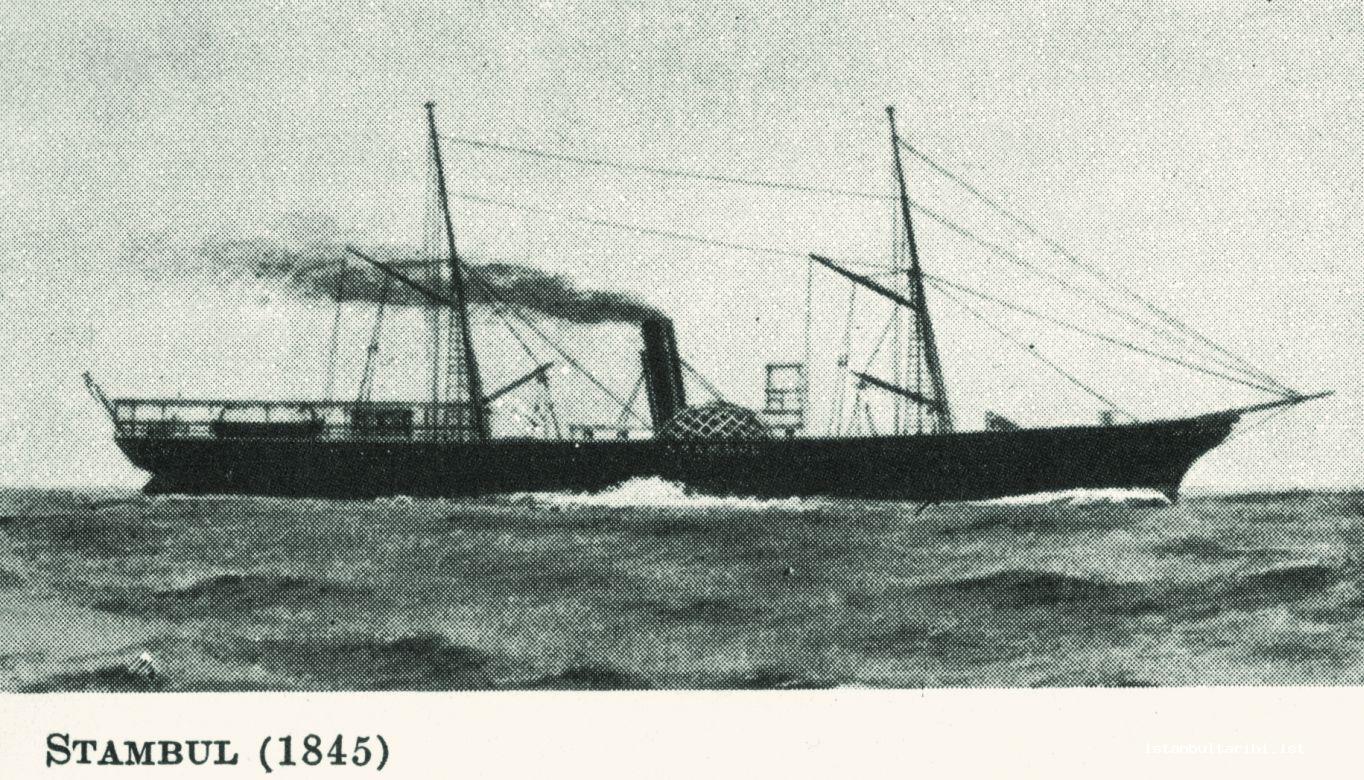

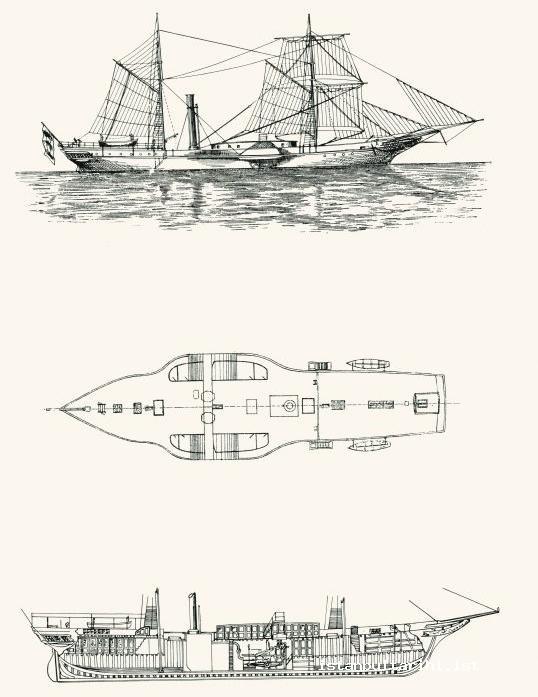

The company started out with a capital of 1,000,000 florins, and ordered six steamboats; Franz von Reyer, chairman of the board of directors of the company, initially set out to gather information about eastern ports.13 The first ship ordered from England arrived in Trieste on March 11, 1837. This ship, measuring forty-one meter in length and called Arciduca Ludovica,14 departed from Trieste on May 16, 1837, under the command of Captain Giovanni Paolo Triscolo; it carried fifty-three passengers and completed the first journey by travelling to Istanbul via Ancona, Corfu, Patras, Piraeus, Siros (Syros) and İzmir.15 Even though the company had to deal with problems regarding its establishment in the following year, it continued to transport passengers and freight to Istanbul.

The Erste K.K. Priviligierte Donaudampfschiffahrt-gesellchaft (the first licensed Austrian Danube steamship transportation company), which was established in 1829, began offering scheduled voyages down the Danube in 1831. This company, which had expanded its route to the lower part of the Danube within Ottoman borders, entered the sea transport business with six steamships that had been purchased in 1836.16 Within the same year the company opened the Istanbul-Trabzon, Istanbul-İzmir and Istanbul-Kalas routes and began offering scheduled voyages.17 However, the Donaudampfschiffahrtgesellchaft began to suffer losses in its sea routes from the 1840s onwards; as a result it was decided to sell the six steamships to Lloyd, via the mediation of the Austrian government.18 An agreement was signed in 1845 and the aforementioned ships joined the Lloyd’s fleet; as a result, Lloyd was now an important part of the traffic that sailed into Istanbul, both from the Black Sea as well as from the Mediterranean.

The Lloyd’s Agency, Post Office and Coal Storage Facility in Istanbul

Austria, which began carrying post within the Ottoman State in 1721,19 began to accept letters from civilians from 1726 on.20 Couriers, who had earlier travelled in an irregular manner, began scheduled delivery, once a month, from 1746 onwards; the Treaty of Sistova institutionalized these scheduled shipments.21 By this time, Austrian consulates had also begun to transport commercial mail; however, it is necessary to state that the transition from a diplomatic courier to a commercial postal service was the result of circumstances, and not based on any written agreement.22

|

Table 2- Lloyd Routes Connecting with Istanbul |

||

|

Route |

Ports of Call |

Explanation |

|

Trieste-Istanbul |

Siros, Piraeus, Çeşme, İzmir, Lesbos, Babakale, Bozcaada, Çanakkale, Gelibolu |

Zante (Zakynthos) and Chios were also added to the ports of call after 1835. The voyages took place once a week. |

|

The Thessaly Route |

Istanbul, Gelibolu, Çanakkale, Larissa, Volos, Stylis |

This route, which began in 1853, was divided into two in 1857, with two different routes being established: Istanbul, Gelibolu, Çanakkale, Thessaloniki and Istanbul, Gelibolu, Çanakkale, Kavala, Volos. |

|

Istanbul-Alexandria |

İzmir |

This express line began in 1837, but was closed the following year. The voyages began in 1853 once again, and continued without interruption until 1914. |

|

Istanbul-Kalas |

Express |

This voyage took place once a week. |

|

Istanbul-Trabzon |

Sinop, Ordu, Giresun, İnebolu |

The voyage took place once a week. It was extended to Batumi later on. |

Source: The data in this table are taken from Tranmer, Austrian Post Offices, p. 13; Stefani et. al., Il Lloyd Triestino, p. 240-241 and BOA, Y.PRK.ASK, no. 102/39.

Over time, the offices of Lloyd’s Insurance Department, which were located in numerous ports, began to take on a variety of roles and duties. The offices were the steamboat representatives in the cities in which they were located and acted as Austrian consular agencies in places where there were no Austrian consulates;23 in addition they managed the Lloyd Post Office. As was the case in many Ottoman port cities, the company also established a post office in Istanbul; however, this did not remain open long, and was only able to operate from 1861 to 1887.24 The mail coming to Istanbul from within the Ottoman State, as well as that from Austrian post offices located outside of the country, were transported on Lloyd ships both before 1887, as well as after this date.

The Lloyd Post Office, located close to the Galata shore, received letters and parcels up until the departure time of the relevant ship.25 It is clear that that this practice, along with the existence of little or no formalities, played a decisive role in the preference of the Lloyd Post Office, despite the lack of competitive pricing.26 The employees at the Lloyd Post Office would begin work at seven in the morning, have a lunch break from twelve to three, and complete their shifts at seven. However, an employee would be at the Lloyd Post Office up until thirty minutes before the ship sailed into the port; in addition, someone would be in the office during the entire time the ship was in port, and up until thirty minutes after it sailed, supervising the transfer of the packages.27

The routes displayed in Table 2 were those that were directly connected with the Istanbul Port. On the other hand, the port cities connected to Istanbul by Lloyd were not limited to only these. For instance, the Lloyd’s connection between Istanbul and important Adriatic ports, such as Venice and Rijeka, cannot be understood from this table, which only shows direct routes. A connecting port would be used to get to these cities; a steamboat stopping at Venice would carry the commercial goods, passengers or post packages it picked up here to areas determined as connecting ports, such as Syros, Piraeus or Rhodes. The post delivered to the ship in these ports for transport to Istanbul would be sent there via another ship that also stopped at these connecting ports. As a result, the connection between Istanbul and all the ports at which Lloyd berthed were ensured.

All marine transport companies stored the necessary coal for the steamboats at various ports. One of Lloyd’s coal storage facilities was in Istanbul. Even though the Ottoman government wanted to eliminate this storage facility, located near Unkapanı, as it was causing environmental pollution, it was unable to do so;28 in fact, in the twentieth century, in addition to this storage facility, which no longer met the demands of the company, a second storage facility near Hasköy was rented.29 The company stored the coal it purchased via its Cardiff agency from England,30 and from Trieste and Rijeka,31 as a result of agreements signed with the government, and thus supply the ships. When necessary, the company could also sell coal to the Ottoman government.32

Lloyd’s Istanbul Transportation

The port traffic of Istanbul underwent a tremendous growth period during the nineteenth century; the total amount of imported and exported goods, which was approximately 400,000 tons in the 1830s, had increased to 13,000,000 tons by 1896.33 This increase in the total tonnage, of course, also had an effect on the number of ships that came and went from Istanbul. In response to research carried out by an international commission established in 1869, in order to organize port traffic,34 in 1873 connection buoys were placed at the docks.35 The connection buoys were used to prevent confusion caused by the ships trying to anchor at the port; the number of piers was insufficient and thus the buoys could be used to reserve space for company ships which made regular voyages to Istanbul or for use by government ships. Documents demonstrate that Lloyd had two buoys allocated for its use.36 When, towards the nineteenth century, the Istanbul harbor became suitable for steamboats, the Lloyd Company discontinued the use of buoys and began docking its steamboats at the pier.37

|

Table 3- Istanbul Port Statistics For 1901 |

|||||||||||||

|

FLAG |

From and to the Black Sea |

From the Mediterranean and to the Black Sea |

From and to the Mediterranean Sea |

From the Black Sea and to the Mediterranean |

Total |

||||||||

|

Unit |

Tonnage |

Unit |

Tonnage |

Unit |

Tonnage |

Number (unit) |

Tonnage |

Unit |

Tonnage |

||||

|

Britain |

- |

- |

1.603 |

2.635.783 |

92 |

120.461 |

1.609 |

2.641.998 |

3.304 |

5.398.242 |

|||

|

Greece |

14 |

6.972 |

723 |

791.567 |

139 |

31.925 |

711 |

784.254 |

1.587 |

1.614.718 |

|||

|

Other |

181 |

141.310 |

967 |

1.385.944 |

139 |

87.032 |

953 |

1.370.195 |

2.249 |

2.984.531 |

|||

|

Steamboat |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Hidiviye |

- |

- |

2 |

3.988 |

50 |

54.603 |

2 |

3.088 |

54 |

62.579 |

|||

|

Messageries |

- |

- |

38 |

60.002 |

51 |

103.121 |

38 |

59.366 |

127 |

222.489 |

|||

|

Fraissinet |

- |

- |

15 |

17.182 |

5 |

5.952 |

14 |

15.906 |

34 |

39.040 |

|||

|

Austrian, Lloyd |

20 |

21.698 |

132 |

176.453 |

57 |

82.444 |

132 |

175.199 |

341 |

455.794 |

|||

|

Rus |

94 |

79.780 |

143 |

285.512 |

- |

- |

141 |

278.195 |

378 |

643.487 |

|||

|

Rubattino |

6 |

7.482 |

102 |

161.804 |

3 |

4.572 |

103 |

162.964 |

214 |

336.822 |

|||

|

Georgian Company |

35 |

35.030 |

54 |

28.373 |

91 |

21.345 |

53 |

27.231 |

233 |

111.999 |

|||

|

İdare-i Mahsusa (Ottoman State Steamboat Company) |

90 |

72.280 |

78 |

45.031 |

44 |

22.850 |

41 |

38.451 |

253 |

178.612 |

|||

|

Pan-Hellenic |

- |

- |

56 |

48.813 |

2 |

1.153 |

57 |

49.273 |

115 |

99.239 |

|||

|

Total |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

8.880 |

12.147.552 |

|||

Source: A&P Records, Diplomatic and Consular Reports on the Trade and Finance of Turkey, Report for the Year 1901 on the Trade of Constantinople, London 1902, p. 26.

|

Table 4- Istanbul Port Statistics for the Year 1902 |

||||||||||

|

FLAG |

From and to the Black Sea |

From the Mediterranean and to the Black Sea |

From and to the Mediterranean Sea |

From the Black Sea and to the Mediterranean |

Total |

|||||

|

Unit |

Tonnage |

Unit |

Tonnage |

Unit |

Tonnage |

Unit |

Tonnage |

Unit |

Tonnage |

|

|

Britain |

- |

- |

2.060 |

3.622.591 |

103 |

158.747 |

2.062 |

3.894.399 |

4.225 |

7.405.737 |

|

Greece |

9 |

4.785 |

841 |

939.366 |

461 |

87.691 |

831 |

985.688 |

1.842 |

1.917.480 |

|

Other |

239 |

186.796 |

1.139 |

1.741.591 |

136 |

90.088 |

1.132 |

1.727.580 |

2.646 |

3.746.055 |

|

Steamboat |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hidiviye |

- |

- |

1 |

2.106 |

53 |

66.320 |

1 |

2.106 |

55 |

70.532 |

|

Messageries |

- |

- |

39 |

62.433 |

48 |

97.728 |

39 |

63.074 |

126 |

223.240 |

|

Fraissinet |

- |

- |

12 |

13.828 |

2 |

2.552 |

13 |

15.104 |

27 |

31.484 |

|

Austria, Lloyd |

26 |

29.893 |

131 |

180.891 |

54 |

81.462 |

130 |

179.223 |

341 |

471.469 |

|

Rus |

104 |

88.081 |

145 |

265.432 |

- |

- |

143 |

261.387 |

392 |

614.900 |

|

Rubattino |

- |

- |

114 |

184.932 |

5 |

7.502 |

112 |

180.593 |

231 |

378.077 |

|

Georgian Company |

25 |

21.065 |

60 |

36.182 |

112 |

20.222 |

57 |

34.898 |

254 |

118.367 |

|

İdare-i Mahsusa |

67 |

59.369 |

70 |

41.566 |

29 |

27.612 |

34 |

31.761 |

200 |

160.308 |

|

Pan-Hellenic |

- |

- |

56 |

53.544 |

- |

- |

55 |

52.592 |

111 |

106.126 |

|

Total |

470 |

389.989 |

4.668 |

7.144.517 |

703 |

595.924 |

4.609 |

7.108.345 |

10.450 |

15.238.775 |

Source: A&P Records, Diplomatic and Consular Reports on the Trade and Finance of Turkey, Report for the Year 1902 on the Trade of Constantinople, London 1903, p. 25.

|

Tablo 5- Istanbul Port Statistics for the Year 1904 |

||||||||||

|

FLAG |

From and to the Black Sea |

From the Mediterranean and to the Black Sea |

From and to the Mediterranean Sea |

From the Black Sea and to the Mediterranean |

Total |

|||||

|

Unit |

Tonnage |

Unit |

Tonnage |

Unit |

Tonnage |

Unit |

Tonnage |

Unit |

Tonnage |

|

|

Britain |

1 |

1.203 |

1.897 |

3.536.718 |

92 |

141.388 |

1.894 |

3.530.497 |

3.884 |

7.209.806 |

|

Greece |

18 |

10.432 |

915 |

1.092.554 |

191 |

45.798 |

910 |

1.097.013 |

2.034 |

2.245.797 |

|

Italian |

- |

- |

236 |

356.091 |

8 |

8.397 |

236 |

356.157 |

480 |

720.555 |

|

Austro-Hungary |

17 |

9.820 |

188 |

350.715 |

1 |

1.995 |

187 |

350.132 |

393 |

712.662 |

|

Germany |

1 |

1.389 |

155 |

241.903 |

11 |

28.815 |

153 |

240.904 |

320 |

513.013 |

|

Others |

249 |

181.034 |

441 |

594.256 |

124 |

60.699 |

427 |

605.556 |

1.241 |

1.441.515 |

|

Steamboat |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hidiviye |

- |

- |

1 |

2.106 |

55 |

77.296 |

1 |

2.106 |

57 |

81.508 |

|

Messageries |

- |

- |

41 |

75.196 |

45 |

91.326 |

45 |

76.907 |

134 |

243.429 |

|

Fraissinet |

- |

- |

16 |

22.651 |

8 |

10.951 |

17 |

23.572 |

41 |

57.174 |

|

Austria, Lloyd |

7 |

9.410 |

139 |

204.886 |

86 |

119.095 |

414 |

208.780 |

373 |

542.171 |

|

Rus |

114 |

82.581 |

158 |

265.129 |

- |

- |

155 |

259.657 |

427 |

607.367 |

|

Rubattino |

- |

- |

113 |

192.510 |

5 |

8.140 |

112 |

190.901 |

230 |

391.551 |

|

İdare-i Mahsusa |

49 |

39.986 |

36 |

27.112 |

23 |

25.883 |

18 |

17.495 |

126 |

110.476 |

|

Georgian Company |

39 |

29.034 |

35 |

16.506 |

79 |

23.245 |

33 |

12.492 |

186 |

81.277 |

|

Pan-Hellenic |

- |

- |

55 |

53.699 |

- |

- |

56 |

54.591 |

111 |

108.290 |

|

Total |

495 |

364.889 |

4.429 |

7.031.944 |

728 |

643.028 |

4.385 |

7.026.760 |

10.037 |

15.066.621 |

Source: A&P Records, Diplomatic and Consular Reports on the Trade and Finance of Turkey, Report for the Year 1904 on the Trade of Constantinople, London 1905, p. 26.

|

Table 6- Istanbul Port Statistics for the Year 1905 |

||||||||||

|

FLAG |

From and to the Black Sea |

From the Mediterranean and to the Black Sea |

From and to the Mediterranean Sea |

From the Black Sea and to the Mediterranean |

Total |

|||||

|

Unit |

Tonnage |

Unit |

Tonnage |

Unit |

Tonnage |

Unit |

Tonnage |

Unit |

Tonnage |

|

|

Britain |

- |

- |

1.740 |

3.285.186 |

67 |

135.279 |

1.734 |

3.272.535 |

3.561 |

6.693.000 |

|

Greece |

43 |

23.727 |

994 |

1.193.824 |

232 |

62.508 |

989 |

1.192.990 |

2.258 |

2.473.049 |

|

Italy |

- |

- |

236 |

330.184 |

4 |

4.041 |

235 |

328.556 |

475 |

662.781 |

|

Austro-Hungary |

21 |

11.235 |

206 |

412.341 |

3 |

1.134 |

206 |

412.341 |

436 |

837.051 |

|

Germany |

106 |

71.530 |

514 |

664.302 |

101 |

55.017 |

506 |

659.147 |

1.227 |

1.449.996 |

|

Steamboat |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hidiviye |

- |

- |

2 |

2.855 |

63 |

97.883 |

2 |

2.855 |

67 |

103.593 |

|

Messageries |

- |

- |

52 |

96.484 |

60 |

136.597 |

52 |

96.452 |

164 |

329.533 |

|

Fraissinet |

- |

- |

25 |

37.437 |

3 |

3.799 |

25 |

37.626 |

53 |

78.862 |

|

Austria, Lloyd |

2 |

2.464 |

133 |

202.116 |

82 |

117.629 |

135 |

204.555 |

352 |

526.764 |

|

Rus |

102 |

82.237 |

137 |

233.011 |

- |

- |

136 |

232.265 |

375 |

547.513 |

|

Rubattino |

- |

- |

98 |

171.566 |

18 |

28.804 |

99 |

172.107 |

215 |

372.477 |

|

İdare-i Mahsusa |

37 |

20.236 |

28 |

25.923 |

6 |

5.552 |

26 |

29.381 |

97 |

81.092 |

|

Georgian Company |

35 |

35.647 |

29 |

19.767 |

30 |

12.891 |

23 |

11.480 |

117 |

79.785 |

|

Pan-Hellenic |

1 |

962 |

61 |

59.819 |

2 |

1.843 |

60 |

59.305 |

124 |

121.929 |

|

Total |

347 |

248.038 |

4.389 |

6.937.987 |

702 |

635.725 |

4.358 |

6.913.930 |

9.796 |

14.785.680 |

Source: A&P Records, Diplomatic&Consular Reports on the Trade and Finance of Turkey, Report for the Year 1905 on the Trade of Constantinople, London 1906, p. 26.

|

Table 7- Istanbul Port Statistics for the Year 1906 |

|||||||||||||

|

Bandıra |

From and to the Black Sea |

From the Mediterranean and to the Black Sea |

From and to the Mediterranean Sea |

From the Black Sea and to the Mediterranean |

Total |

||||||||

|

Unit |

Tonnage |

Unit |

Tonnage |

Unit |

Tonnage |

Unit |

Tonnage |

Unit |

Tonnage |

||||

|

Britain |

5 |

2.110 |

1.783 |

3.488.474 |

79 |

1.781 |

1,781 |

3.430.180 |

3.648 |

7.099.469 |

|||

|

Greece |

63 |

32.963 |

946 |

1.133.173 |

260 |

63.957 |

937 |

1.127.762 |

2.206 |

2.357.855 |

|||

|

Italy |

- |

- |

191 |

247.736 |

4 |

5.468 |

191 |

247.736 |

386 |

500.940 |

|||

|

Austro-Hungary |

21 |

11.235 |

172 |

344.469 |

2 |

2.252 |

172 |

344.469 |

367 |

702.425 |

|||

|

Germany |

- |

- |

172 |

294.900 |

9 |

18.433 |

171 |

292.691 |

352 |

606.024 |

|||

|

Others |

174 |

112.185 |

546 |

751.890 |

107 |

69.376 |

540 |

742.253 |

1.367 |

1.675.803 |

|||

|

Steamboat |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Hidiviye |

- |

- |

2 |

3.886 |

59 |

100.829 |

2 |

3.886 |

63 |

108.601 |

|||

|

Messageries |

- |

- |

50 |

93.513 |

51 |

118.346 |

54 |

101.221 |

155 |

313.080 |

|||

|

Fraissinet |

- |

- |

26 |

41.294 |

5 |

5.355 |

27 |

42.717 |

58 |

89.366 |

|||

|

Austria Lloyd |

2 |

2.287 |

134 |

203.027 |

72 |

103.410 |

137 |

206.139 |

345 |

514.863 |

|||

|

Rus |

99 |

75.959 |

146 |

254.304 |

- |

- |

144 |

245.767 |

389 |

576.030 |

|||

|

Rubattino |

- |

- |

103 |

181.766 |

13 |

21.330 |

103 |

181.893 |

219 |

384.989 |

|||

|

İdare-i Mahsusa |

52 |

41.006 |

29 |

21.764 |

2 |

1.863 |

22 |

21.711 |

105 |

86.344 |

|||

|

Georgian Company |

65 |

62.051 |

8 |

5.247 |

26 |

11.609 |

4 |

1.786 |

103 |

80.693 |

|||

|

Pan-Hellenic |

- |

- |

52 |

49.272 |

1 |

460 |

53 |

50.142 |

106 |

99.874 |

|||

|

Total |

481 |

339.796 |

4.360 |

7.114.715 |

690 |

651.393 |

4.333 |

7.090.452 |

9.869 |

15.196.356 |

|||

Source: A&P Records, Diplomatic and Consular Reports on the Trade and Finance of Turkey, Report for the Year 1906 on the Trade of Constantinople, London 1907, p. 18.

In terms of establishment, Lloyd was a postal transportation company; steamboats were not developed enough to allow the transportation of freight and passengers in the 1830s, and were used mostly for the transportation of letters and parcels. However, developments brought the steamboat to the fore for the transportation of freight and goods. Nevertheless, it cannot be claimed that Lloyd was a leader in the transportation of goods and freight; the total amount of goods Lloyd transported to Istanbul did not amount to even 1 % of the amount transported by its competitors. In 1855 the Lloyd Company actually attempted to engage in coastal trading between the Prince Islands and the Golden Horn;38 however, because the government made tremendous efforts to protect its coastal rights in the Marmara Sea via the Bosphorus docks, the company was unable to realize this aim.39 It can be ascertained that the actual goals of the company for transporting goods and merchandise were the provincial ports. In fact, Lloyd’s share of total provincial sea transportation was twenty-five percent.40 The reason why the amount of goods transported to Istanbul by Lloyd, a company that was active in Ottoman ports, was lower than that of other transportation companies was because this company also provided transit transportation and warehouse services. It is also known that from 1849 on, Lloyd, which had introduced the warehouse practice to the Ottoman Empire, also embezzled a significant amount of goods from Ottoman authorities.41 When the warehouses were brought under government control, the company began to smuggle transit goods, avoiding the revenue officers’ inspection by transferring the goods from one ship to another, particularly at the Port of Istanbul. 42

Documents demonstrate that more than 300 Lloyd steamboats travelled to Istanbul at the beginning of the twentieth century, bringing with them between 400,000 and 500,000 tons of goods.43 As stated above, this amount was only around 1 % of the total goods and merchandise entering and leaving the Istanbul Port. At this period, the amount imported by the Ottoman government from Austria was around 3 % .44 When this is taken together with the transportation that Lloyd carried out to the provincial ports, it can be understood that Austria’s exports to the Ottoman Empire were limited to those transported by Lloyd.

CONCLUSION

When analyzed statistically, it can be seen that Lloyd’s marine operations to and from Istanbul were smaller than their operations at other Ottoman ports; however, these voyages were more important for the residents of Istanbul, and their perception of Lloyd went beyond mere numbers. It was as if the company embodied Austria, or to take it further, as if it made Europe more tangible for the residents of Istanbul. The reason for this was that Lloyd was one of the first companies to provide steamboat transportation; in addition, it continued to operate without interruption from 1837 until the First World War. Moreover, Lloyd provided the limited amount of commercial transportation between the Ottoman State and Austria, so naturally people saw it as an extension of Austria. Another reason behind this perception was that some of the company agencies also carried out the duties of the Austrian consulate.

The boycott against Austrian merchandise, which began when Austria annexed Bosnia-Herzegovina on October 5, 1908, also affected Lloyd, the tangible face of Austria in Ottoman territory. In this period, the trade volume of Austrian post throughout the country decreased; however, contrary to this general situation, the trade volume of the Istanbul Post Office increased.45 In fact, during the boycott, no backlash, either from the people of Istanbul or from the government, occurred to affect the company. Notwithstanding, after the breakout of the First World War, private steamboats were included into the Austro-Hungarian fleet to be used in supply services. When at the end of the war, Trieste, the city in which the general headquarters of Lloyd were located, remained within Italian borders, the company continued to make journeys to Istanbul from 1919 onwards under the Italian flag under the name Lloyd Triestino.

FOOTNOTES

1 According to the Declaration of Association, dated April 20, 1833, these seven partners were: Ang. Giannichesi, Marco Parente, C. L. Bruck, G. G. Sartorio, G. B. Silverio, G. Padovani and Cesare Cassis Faraone (Giuseppe Stefani et. al., İl Lloyd Triestino: Contributo Alla Storia İtaliana della Navigazione Marittima, Verona: Officine grafiche A. Mondadori, 1938, p. 17).

2 Ronald E. Coons, Steamships, Statesmen and Bureaucrats: Austrian Policy Towards the Steam Navigation Company of the Austrian Lloyd 1836-1848, Wiesbaden : Steiner, 1975, pp. 5-6.

3 Coons, Steamships, Statesmen and Bureaucrats, p. 27.

4 İlber Ortaylı, Osmanlı’da Milletler ve Diplomasi: Seçme Eserleri III, Istanbul: Türkiye İş Bankası Kültür Yayınları, 2008, p. 205.

5 For a brief biography of von Bruck, who served as Austrian ambassador to Istanbul for a year as well as the Austrian minister of finance for a period, prepared immediately after his death, see: C.A.S., Finanzminister Karl Freiherr von Bruck, Wien: Fr. Förster u. Brüder, 1861.

6 Coons, Steamships, Statesmen and Bureaucrats, p. 32.

7 Coons, Steamships, Statesmen and Bureaucrats, p. 35.

8 Stefani et. al., İl Lloyd Triestino, p. 23.

9 Coons, Steamships, Statesmen and Bureaucrats, p. 39.

10 Fünfundsiebzig Jahre Österreicher Lloyd 1836-1911, Trieste: Österreichischer Lloyd, 1911, p. 10.

11 A&P Records, Foreign Office Miscellaneous Series No 41 History of the Austrian-Hungarian Steam Navigation Company Lloyd, London 1887, p. 1.

12 A&P Records, History of the Austrian Lloyd. p. 1; Regolamento per le Agenzie della Prima Sezione del Lloyd Austriaco, Trieste: Tipl. del Lloyd austr.,1846, p. 1; a facsimile of the regulations can be found in: Stefani et al., Il Lloyd Triestino, p. 64.

13 A&P Records, History of the Austrian Lloyd, pp. 1-2.

14 Stefani and others, Il Lloyd Triestino, p. 83; A&P Records, History of the Austrian Lloyd, p. 2.

15 Anthony Virvilis, “Correspondence Between Greece and Egypt During 1833-1881”, Philotelia, 1999, no. 596, p. 13; A&P Records, History of the Austrian Lloyd, p. 2; Stefani et. al, Il Lloyd Triestino, p. 85; Coons, Steamships, Statesmen and Bureaucrats, p. 63; Keith Tranmer, Austrian Post Offices Abroad, Sussex: Austrian Stamp Club of Great Britain, 1976, vol. 8, p. 14.

16 Henry Hajnal, The Danube: Its Historical, Political and Economic Importance, The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1920, pp. 121-126, 134-136; Virgina Paskaleva, “Osmanlı Balkan Eyaletleri’nin Avrupalı Devletlerle Ticaretleri Tarihine Katkı (1700-1850)”, İFM, 1968, vol. 27, no. 1-2, pp. 68-69.

17 R. T. Claridge, A Guide Along the Danube from Vienna to Constantinople, Smyrna, Athens the Morea the Ionian Islands and Venice, London: Howlett and Son Priters, 1837, p. 5.

18 Coons, Steamships, Statesmen and Bureaucrats, pp. 114-117.

19 M. Bülent Varlık, “Bir Yarı Sömürge Olma Simgesi: Yabancı Posta Örgütleri”, TCTA, vol, p. 1653.

20 Ayşegül Okan, “The Ottoman Postal and Telegraph Services in the Last Quarter of the Nineteenth Century”, post-graduate thesis, Bosphorus University, 2003, p. 33.

21 Varlık “Yabancı Posta Örgütleri”, vol. 4, 1653.

22 Varlık “Yabancı Posta Örgütleri”, vol. 4, 1654; Mübahat S. Kütükoğlu, “Osmanlı İktisadi Yapısı”, Osmanlı Devleti Tarihi, ed. Ekmeleddin İhsanoğlu, Istanbul: Feza Gazetecilik, 1999, vol. 2, p. 603; Yaşar Türedi et. al., Geçmişten Günümüze Posta, Ankara: PTT Genel Müdürlüğü, 2007, p. 173; Taner Aslan, Osmanlı’da Levant Postaları, Ankara: Berikan Yayınevi, 2012, pp. 116-117; Okan, “The Ottoman Postal and Telegraph Services”, pp. 33-34.

23 Rudolf Agstner, “Zur Geschichte der Österreichischen (Österreich-Ungarischen) Konsulate in der Türkei 1718-1918”, Österreichen in Istanbul, ed. Rudolf Agstner and Elmar Samsinger, Berlin: Lit Verlag, 2010, p. 146.

24 The reason the post office was closed was because there was also an Austrian government post office in Istanbul; two post offices in the same city would cause confusion. (Andreas Patera, “Die Örtliche, Bauliche und Raumliche Situation der Österreichischen Postamter in Konstantinopel”, Österreichen in Istanbul, ed. Rudolf Agstner ve Elmar Samsinger, Berlin: Lit Verlag, 2010, p. 239).

25 Tanju Demir, “15 dakika öncesine kadar (up until 15 minutes before) (“Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’nda Deniz Posta Taşımacılığı ve Vapur Kumpanyaları”, OTAM, 2006, no. 17, p. 6); however, Patera states that post would be accepted “up until 90 minutes before”. (“Österreichischen Postamter”, p. 254) .

26 Joseph Nalpas and Jacob de Andria, Annuaire des Commerçants de Smyrne & De L’Anatolie, İzmir: Imprimerie Commerciale G. Timoni and Co., 1893, p. 72.

27 Patera, “Die Örtliche”, p. 239.

28 BOA, MV, 42/68, 24 April 1889; BOA, DH.MKT, 1908/81, 7 January 1892.

29 BOA, ZB, 375/87, 6 February 1907.

30 A&P Records, Foreign Office 1894, Annual Series Diplomatic and Consular Reports on Trade and Finance: Austria-Hungary, London: HMSO,1894, p. 24

31 A&P Records, History of the Austrian Lloyd, p. 5.

32 BOA, HR.MKT, 288/14, 18 May 1859; BOA, HR.TO, 327/39, 24 June 1867, document 2.

33 Wolfgang Müller-Wiener, Bizans’tan Osmanlı’ya İstanbul Limanı, İstanbul 2003, pp. 132, 143.

34 BOA, HR.HMŞ.İŞO, 181/61, August 17, 1898, document 2.

35 Wiener, İstanbul Limanı, p 133.

36 BOA, HR.HMŞ.İŞO, 181/61, August 17, 1898, document 2.

37 BOA, HR.HMŞ.İŞO, 181/62, April 27, 1899.

38 BOA, HR.MKT, 108/79, May 14, 1855.

39 For the debates about coastal transport on the Bosphorus and Marmara, see: Kaori Komatsu, “XIX. Yüzyıl Osmanlı-İngiliz Deniz Ticareti Münasebetlerinde ‘Kabotaj’ Meselesi”, Osmanlı, ed. Güler Eren, Ankara: Yeni Türkiye Yayınları, 1999, vol. 3, pp. 373-379; İlhan Ekinci, “Osmanlı Devleti’nde Marmara’da Kabotaj Tartışmaları”, Afyon Kocatepe Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 2006, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 99-122.

40 Paul Fesch, Abdülhamid’in Son Günlerinde “İstanbul”, tr. Erol Üyepazarcı, Istanbul: Pera Turizm ve Ticaret, 1999, p. 517.

41 BOA, HR.MKT, 27/44, 22 August 1849.

42 BOA, Y.A.HUS, 453/138, 8 August1893, document 1.

43 Please see tables below.

44 F. R. Bridge, “Habsburg Monarşisi ve Osmanlı İmparatorluğu 1900-1918”, Osmanlı İmparatorluğu ve Büyük Güçler, ed. Marian Kent, tr. Ahmet Fethi, Istanbul: Alfa Yayıncılık, 2013, p. 59.

45 Donald Quataert, Osmanlı Devleti’nde Avrupa İktisadi Yayılımı ve Direniş (1881-1908), tr. Sabri Tekay, Ankara: Yurt Yayınevi, 1987, p. 118.