Messageries Maritimes’ Istanbul Routes

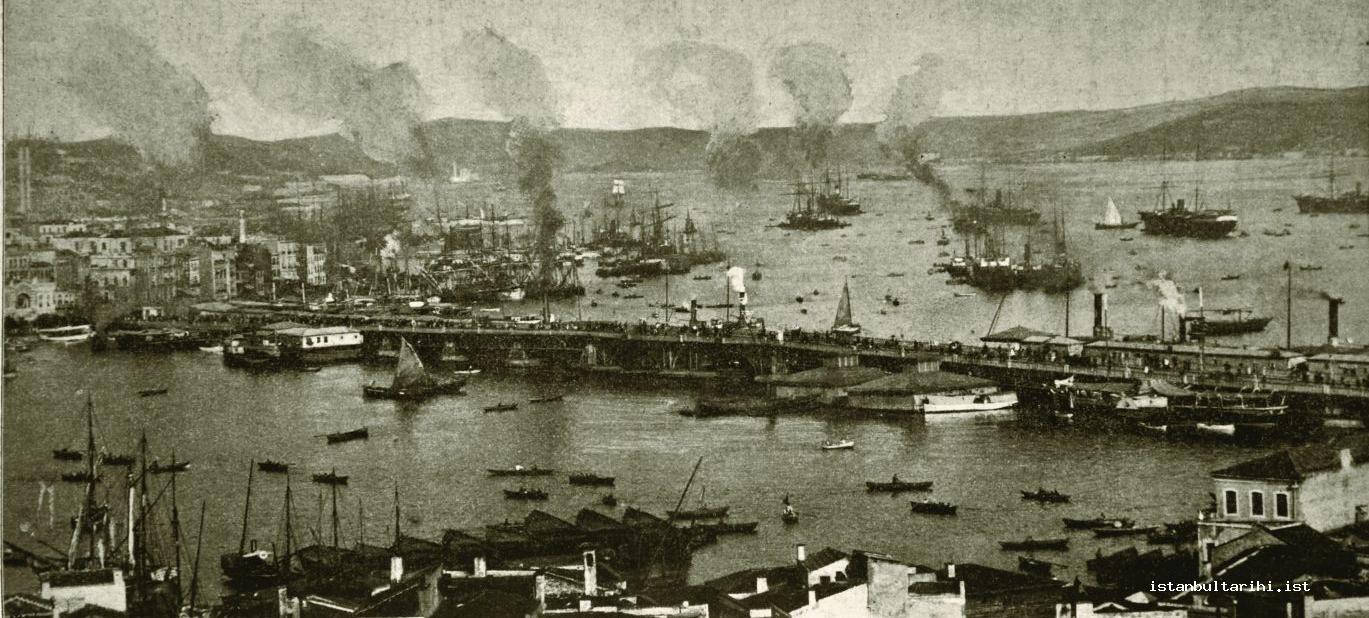

Until the first quarter of the nineteenth century, the French played a prominent role in Istanbul trade. Although severed by the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars, Istanbul trade, which was concentrated in Marseille, began to flourish once again after 1815. All of the merchant ships which sailed under foreign flags stopped by the Istanbul Port were sailboats of various sizes. The Swift, the first English steamboat to enter the Istanbul harbor in 1828, was the harbinger of a new era in commerce. Just a short time after this event, in 1831, A. C. Comte de Guillemont (1774-1840), the French ambassador to Istanbul, negotiated a regular route between Marseille and Istanbul by steamboat; in the same year, English entrepreneurs started journeys using two steamboats along a route that stretched from Istanbul to Trabzon, transporting goods from Iran.1

The French joined these enterprises with the Le Service Maritime Postal de l’Etat, established in 1835. This Postal Company started up three voyages a month on a regular basis; the first voyage was completed using the steamboat Scamandre between Marseille and Istanbul in 1837.2 In the mid-1840s, transportation companies from a variety of nations were involved in commercial activities in the Istanbul Port. Opportunities provided by the Treaty of Balta Limanı (dated August 16, 1838) undeniably played an important role in bringing about this situation.3 A traveler who visited Istanbul on the steamboat belonging to the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company in the 1840s stated that he saw Austrian, Russian, English, Greek and American steamboats anchored in the Istanbul Port.4

Except for the Le Service Maritime Postal de l’Etat, most of the foreign transportation companies entering Istanbul Port transported post, passengers or commodities. Because the main aim of the Le Service Maritime Postal de l’Etat was to provide a connection between France and Istanbul, it had very few commercial concerns.5 Rostand et Compagnie, also known as Compagnie des Paquebots à Vapeur du Levant, attempted to meet the commercial transportation needs between Marseille and Istanbul.6 Having been granted permission by the Ottoman government7 to operate steamboats between Marseille and İzmir and Marseille and Istanbul, the Rostand Company carried out its first voyage with the Hellespont steamboat on July 11, 1846.8 However, negatively affected by competition with the Austrian Lloyd Company (Lloyd Autrichien), which was using the same route, from the last months of 1846 Rostand Company decreased their voyage frequency from twice a month to once a month.9

Le Service Maritime Postal de l’Etat and the Rostand Company were established in order to transport mail and commodities from France to the Orient; however, this was far from being a satisfactory solution. Le Service Maritime Postal de l’Etat was essentially a sub-unit of the French naval forces and had few commercial concerns, while the Rostand Company was a small family business that had only three steamboats in its fleet; thus, neither could satisfy the commercial needs for the route between Marseille and Istanbul.10 These two companies stood no chance against leading transportation companies like the English Peninsular & Oriental and the Austrian Lloyd Company. Hence, by 1850, Le Service Maritime Postal de l’Etat had lost over 37.000.000 francs,11 and the condition of the Rostand Company was no better.12

Realizing that it was not possible to compete with large transportation companies like the English Peninsular & Oriental or the Austrian Lloyd Company, but wanting to ensure commercial relations between Istanbul and the Levant, on February 28, 1851 the French government granted privileges for transporting mail to the Mediterranean to La Compagnie Messageries des Nationales, a land and maritime transportation company operating in France.13 The name of the company was Compagnie des Services Maritimes des Messageries Nationales); 14 this was shortened to Messageries Maritimes.15 The company’s Istanbul agency was managed by C. Beuf (1851-1856), Jules Girette16 (1856-1873), M. Grugoli (1873-1875), M. Bentraud17 (?-1883), Martin des Pallières (?-1891), Charles Dechaud (?-1907), M. Nicoullaud (1907-1909), Fernand Pican (1909-1910), Maurice Lecouflet (1910-1911) and Andrien Monge (1912-?).18

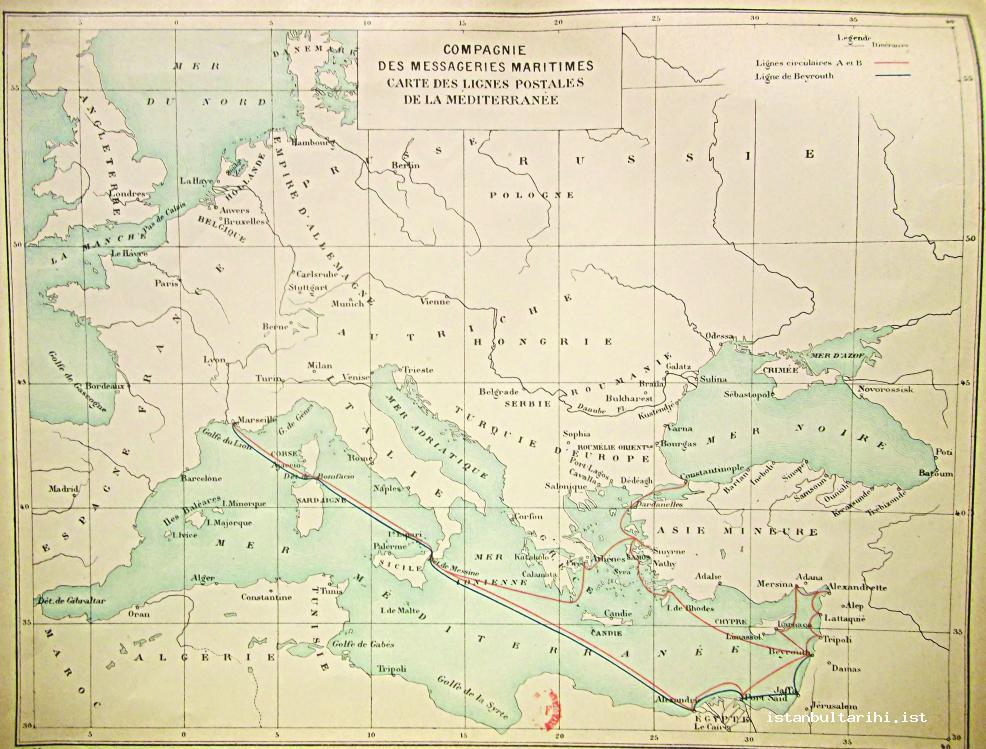

With the establishment of Messageries Maritimes, steamboats working on the Istanbul route belonging to Le Service Maritime Postal de l’Etat and the Rostand Company joined the fleet of the new company. In 1851, thirteen of the sixteen existing steamboats (the Eurotas, Leonidas, Lycurgue, Mentor, Scamandre, Tancréde, Sesostris, Osiris, Nil, Louqsor, Egyptus, Caire and the Telemaque19) belonging to the Le Service Maritime Postal de l’Etat and the remaining three steamboats (Hellespont, Bosphore and Oronte) belonging to the Rostand Company were bought by Messageries Maritimes.20 The number of steamboats operating with this company increased to forty in 1855 and sixty-seven in 1900.21 The administration of Messageries Maritimes designated Istanbul as the base of operations in the Levant. For this reason, Eastern Mediterranean routes were based in Istanbul.22 According to the agreement dated 1851 between the administration of Messageries Maritimes and the French government, the company’s steamboats were to go from Marseille to Istanbul once every ten days, using a route from Malta, Siros, İzmir, Lesbos, Çanakkale and Gallipoli; once every twenty days they would go from Istanbul to Alexandria via İzmir, Rhodes, Mersin, İskenderun, Latakia, Tripoli, Beirut and Jaffa.23

|

Table 1- Freight transported by Messageries Maritimes during the Crimean War on the Istanbul-Black Sea route

|

||||

|

Year |

Passenger |

Commodities |

||

|

|

Military |

Civilian |

Military (Francs) |

Civilian (Francs) |

|

1854 1855 1856 |

28.800 53.128 38.496 |

15.747 47.128 35.985 |

6.872.000 9.768.000 3.672.924 |

8.515.181 16.975.436 15.580.875 |

Source: AFL. 1997 002 5199, Assemblée Générale du 31 Mai 1857, pp. 33-36; AFL. 1997 002 5199, Assemblée Générale du 31 Mai 1856, p. 38.

In September 1851, the Messageries Maritimes’ steamboat Scamandre completed its first voyage between Istanbul and Alexandria, while Mentor and Erotas carried out their first voyages between Marseille and Istanbul.24 However, the onset of the Crimean War and France’s involvement in this war changed the destiny of the company; it now entered into an array of agreements with the French Ministry of War to transport infantry, ammunition and wounded soldiers.25 Additionally, while increasing services between Marseille and Istanbul, the Black Sea was added to the network of activity.26 On March 31, 1855, with a supplementary agreement signed with the French Ministry of War, routes between Istanbul and Varna, Istanbul and the Crimean ports, Istanbul and Balaklava and Istanbul and Sevastopol were introduced; these voyages began to take place once a week on a regular basis.27 The company’s route between Istanbul and Alexandria was temporarily changed, now going from İzmir to Alexandria.28 As a result of this change, the company’s steamboats now went from Istanbul to Gallipoli, Çanakkale, Lesbos and İzmir, making 52 postal deliveries a year; they also followed the İzmir, Rhodes, Mersin, İskenderun, Latakia, Tripoli, Jaffa and Alexandria routes, making 26 postal deliveries a year. The French government subsidized the company for the Black Sea and Mediterranean routes.29 Messageries Maritimes provided important logistical support, carrying civilian and military passengers, as well as commodities30 during the Crimean War.31

France’s alignment with the Ottomans in the Crimean War secured great advantages for French companies, particularly for the Messageries Maritimes. In 1856, in response to complaints about lack of piers for steamboats made by the Istanbul representative of the company, Jules Girette,32 the Sublime Porte granted permission to the company in March, 1857 to build a dock, pier, warehouse and wharf near Kireçkapı in Galata.33 However, this transaction occurred during a period in which it was not legal to sell property to foreigners; Istanbul residents protested the granting of this privilege to the company. In response, the Sublime Porte repurchased the dock, pier, warehouse, and wharf at a cost of 900,000 francs; the original price that the Messageries Maritimes had paid was 325,000 francs. The usufruct was leased to the company for 30,000 francs a year for a period of twenty-five years.34

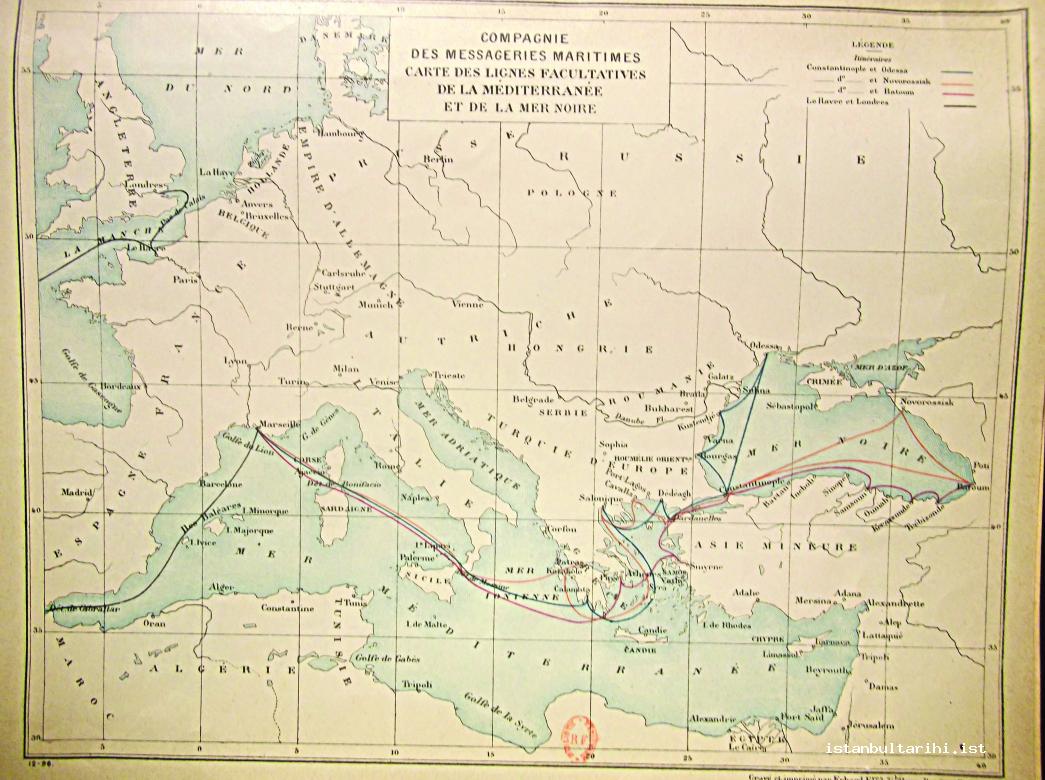

In this way, the company was able to establish the necessary infrastructure in Istanbul Port and made the temporary routes that had been established during the war permanent. After the war, the company’s Danube and Black Sea routes from Istanbul were expanded to include the Lower Danube and Trabzon. According to an agreement between the company and the French government, dated May 29, 1857, the company’s steamboats were to travel once every ten days on a regular basis from Istanbul to Trabzon and from Istanbul to Kalas and Braila.35 The duration of the voyage to Trabzon was specified as lasting ninety hours; for Kalas and Braila it would be 120 hours. The length of these journeys would eventually decrease to twenty-four hours, thanks to technological developments.36 Upon Jules Girette’s request for permission for a trial postal route on the Istanbul-Kalas-Braila route,37 the company’s steamboats started to operate between Istanbul and Braila, Kalas and Tulcea.38 The voyages that departed from Istanbul would stop at Sinop, İnebolu, Samsun, Ünye, Fatsa, Ordu and Giresun, ending at Trabzon;39 however, these journeys could only begin on July 1, 1857 due to the Crimean War.40 The creation of different routes and the opening of agencies, particularly in Samsun and Trabzon, was welcomed by the Sublime Porte.41 On September 1, 1858, the company started regular voyages between Istanbul and Volo (Thessaly) once every fifteen days; from December 8, a voyage between Istanbul and Thessaloniki, solely for commercial purposes, was begun. The French government included these routes as subsidized postal routes.42 With the increasing importance of Istanbul for the company, Kireçkapı Pier became the main stop for the steamboats, due to the new routes.43

Upon the temporary cessation of the Austrian Lloyd Company services between Istanbul and Alexandria in 1859, this gap was filled by the Messageries Maritimes. However, the company’s administration was forced to terminate this service in early 1860, as the French government had not subsidized the route, and the earnings did not compensate for the expenses quickly enough.44

With the establishment of the Third Republic in France, the agreements that were signed between the company and the government were revised. With an agreement drawn up on July 15, 1875, the subsidy for the Black Sea routes was removed and the company’s routes on the Black Sea and the Danube were converted to free-trade routes.45 In addition to this, the postal service between Marseille, Thessaloniki and Istanbul was converted to a free-trade route and its frequency was decreased from once a week to once every fifteen days. In a similar manner, the postal route between Istanbul and Thessaly, which operated once every fifteen days, was also converted into a free-trade route. On March 20, 1875, the French government approved the establishment of a direct postal route between Istanbul and Odessa to replace the earlier routes.46 In this way, the subsidized postal routes in the Mediterranean were designated as a weekly, direct journey to Istanbul from Marseille, a return journey from Istanbul to Marseille every fifteen days via Piraeus, and a return trip every fifteen days via İzmir. Another postal route was to be established; this would go from Istanbul and Syrian ports to Alexandria and take place every fourteen days.47

|

Tablo 2- Passenger and commodity freight revenue of Messageries Maritimes Istanbul Agency in 1882-1883 |

||||||

|

Stops |

Passenger Revenue (francs) |

Commodities Revenue (francs) |

Total (francs) |

|||

|

1882 |

1883 |

1882 |

1883 |

1882 |

1883 |

|

|

Çanakkale İzmir Syria Syra Piraeus Napoli Marseille Odessa İnebolu Samsun Giresun Trabzon Ordu Sinop Constanta Sünne Tulcea Kalas Braila Dedeağaç Port Lagos Kavala Thessaloniki Mont Athos Indo-China |

3.556 14.672 49.247 14.985 33.411 17.307 154.491 11.193 4.877 14.644 6.108 20.845 666 380 8.749 910 1.533 8.923 2.523 1.576 7.571 8.803 20.181 16.711 --- |

2.992 20.218 64.235 10.468 35.173 19.192 138.132 6.025 6.315 16.651 10.232 28.974 1.913 626 7.842 920 964 8.556 1.389 1.789 8.232 5.716 30.874 14.798 --- |

1.211 4.962 31.825 1.924 3.248 15 265.187 5.546 4.399 18.004 6.969 29.568 505 823 10.002 2.352 2.627 35.775 18.156 1.592 6.393 3.791 10.078 971 1.114 |

899 5.969 28.068 4.256 4.367 35 355.184 1.710 5.578 27.096 6.387 48.360 984 1.286 6.566 1.881 2.102 20.662 10.495 1.878 8.367 4.314 10.496 1.101 491 |

4.767 19.634 81.072 16.909 36.559 17.222 419.678 16.729 9.276 32.648 13.077 50.413 1.171 1.203 18.751 3.262 4.160 44.698 20.679 3.168 13.964 12.594 30.259 17.682 1.114 |

3.891 26.187 92.303 14.724 39.540 19.226 493.316 7.735 11.893 43.747 16.619 77.334 2.897 1.912 14.408 2.791 3.066 29.218 11.884 3.667 16.599 10.030 41.370 15.900 491 |

Source: AFL. 1997-002-4404, Compagnie de Messageries Maritimes Agence de Constantinople, Rapport Général de Service Exercice 1882, 1883, Chapitre 4, Trafic.

By the 1880s, most of the company’s routes in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea had been converted to free-trade routes. The premium law, passed in France on January 29, 1881, had a strong influence on the preference of the company administrators for trade routes over subsidized postal routes. According to this law, 1.5 francs would be given for every 1,000 miles of travel to steamboats made in French shipyards and 0.75 francs to steamboats made in foreign shipyards.48 In addition, company administrators adopted the policy of allowing representatives to have autonomy, their salaries being regulated according to the annual earnings of the region in which they were operating. The reasoning for this was based on the principle of laissez faire. With the new system, Istanbul and Alexandria now became main agencies.49 Agencies in the Black Sea, Mediterranean and Danube were affiliated with the main agency in Istanbul; small agencies, like Jaffa and Port Said, were affiliated with the main agency in Alexandria.50 Thus, decisions, such as changing trade routes in the Mediterranean, Black Sea and Lower Danube, as well as the addition of new voyages, were left to the initiative of the Istanbul agency. As Istanbul was the main stopping point, the agency’s passenger and commodity revenue consisted of trade between Istanbul and Marseille and routes that were connected to Istanbul. The Istanbul agency also had connections with various European cities and with Indo-China.51 The table below gives a general idea about the relationship of the Istanbul agency with nearby cities and distant regions.

According to an agreement made between the company and the French government on June 30, 1886, the route between Marseille and Istanbul became a free-trade route.52 In fact, due to political concerns the French government did not want to eliminate the Istanbul postal route; however, as far as the company was concerned, the connection between Thessaloniki and the railroads53 had eased the influx of Central and Eastern European products to the Mediterranean, and thus the commercial importance of Istanbul was on the decline. As a result, the company’s administration converted the Istanbul route to a free-trade route;54 at first the frequency of voyages between Thessaloniki and Istanbul was decreased, and eventually, in 1888, the route was cancelled altogether.55 In 1886 voyages between Istanbul and Trabzon were extended to include Batumi and Poti; these voyages were made once every fifteen days.56 The company started to make weekly voyages along trade routes they had established between Marseille, Istanbul and Odessa and, alternately, between Istanbul and Batumi in 1892.57

The company established a direct trade route to Istanbul via London, Havre and Marseille on January 1, 1889.58 In the following year, it removed the commercial voyages between Istanbul and the Lower Danube (Braila and Kalas).59 By the 1890s, there were significant changes in the French government’s Mediterranean and Black Sea policies. Removal of the subsidy from Istanbul postal routes and the limitation of the Eastern Mediterranean service caused the French public to protest.60 Upon these protests, the French government revised the company’s Mediterranean and Black Sea postal routes; based on an agreement that took effect on July 14, 1895,61 two postal routes to Istanbul were established. On the cyclical A route, a regular fourteen-day postal service was established, with the company steamboats coming to Istanbul via Marseille and then crossing from here to Piraeus and İzmir; the return voyage went from Istanbul to İzmir and Rhodes, or Samos, Beirut and Alexandria, finally docking in Marseille. On the cyclical B route, which started from Marseille, the steamboats went to İzmir and Istanbul via Alexandria, Beirut and Rhodes, or alternatively Samos; on the return journey, they went to Marseille via Istanbul, İzmir and then Piraeus. This route also operated once every two weeks. The company also connected Larnaca (Cyprus), Mersin, İskenderun, Latakia and Tripoli to Beirut in a way that coincided with the cyclical A and B routes. Moreover, in addition to the free routes between harbors in Marseille, Istanbul and the Black Sea, the company committed to a journey to the Thessaloniki Harbor once every two weeks, and in particular, promised to improve its services along the northern coast of the Black Sea.62 In the case of low commercial returns on the Marseille-Istanbul and Black Sea free-trade routes, such as the A and B routes, the company was offered subsidies.63

|

Tablo 3- Passenger and commodity freight revenues of the Istanbul agency Messageries Maritimes between 1881 and 1883 |

|||

|

Year |

Passenger Revenue (Francs) |

Commodities Revenue (Francs) |

Total Revenue (Francs) |

|

1881 1882 1883 |

491.392 421.873 442.214 |

436.804 467.046 558.143 |

928.196 888.919 1.000.357 |

Source: AFL. 1997 002 4404, Compagnie de Messageries Maritimes Agence de Constantinople, Rapport Général de Service Exercice 1881, 1882, 1883, Chapitre 4, Trafic; Chapitre 6, Comptabilite.

Post and Freight Transportation Offered by the Messageries Maritimes in Istanbul

By the end of the nineteenth century, although the steamboat traffic in the Istanbul Harbor was decreasing every day, the routes to Istanbul’s hinterland started to decline. Most of the commodity freight that was shipped by the Istanbul Messageries Maritimes agency was from Anatolia and the Balkans. As a result of the Ottoman loss of Romania and periodic insurrections in the Balkans, some of the freight revenue associated with these regions was lost. In addition, Armenian revolts in Istanbul and Anatolia had a negative impact on Istanbul’s economy, indirectly affecting the company’s revenues. Due to all of these reasons, from the end of the 1880s to the early 1900s the company’s passenger and commodity transportation revenues in Istanbul followed a fluctuating and ultimately declining course. By this time, the commercial activities of Messageries Maritimes in Istanbul consisted only of the transportation of passenger, commodities and post. Passenger and commodity revenues between 1881 and 1883 for the Istanbul agency can be seen in Table 3.

|

Table 4- Messageries Maritimes’ passenger and commodity freight revenue in Istanbul, between 1901 and 1913 |

||||||||||||

|

Year |

Postal route round trip |

Commercial route round trip |

Total |

|||||||||

|

Passenger |

Commodity |

Passenger |

Commodity |

General |

||||||||

|

Number |

Revenue (Francs) |

Parcel |

Revenue (Francs) |

Number |

Revenue (Francs) |

Parcel |

Revenue (Francs) |

Revenue (Francs) |

||||

|

1901 1902 1903 1904 1905 1906 1907 1908 1909 1910 1911 1912 1913 |

7.580 7.034 5.978 4.892 7.370 7.286 7.557 8.568 9.648 13.213 11.485 9.375 11.538 |

294.568 292.040 265.309 205.870 355.110 322.044 342.736 356.788 440.835 600.016 606.267 411.973 471.073 |

53.976 56.493 29.693 19.569 25.947 37.767 37.038 30.259 37.136 42.559 74.399 21.399 2.634 |

102.793 90.020 70.429 65.659 100.711 115.649 116.239 98.350 138.632 193.949 190.751 115.105 162.143 |

1.974 2.809 2.937 2.194 2.793 3.455 3.727 3.393 3.349 4.385 2.911 4.309 7.825 |

54.450 89.467 92.590 69.123 87.600 114.682 108.681 91.458 100.216 118.610 98.897 146.470 228.992 |

28.398 48.008 49.075 57.922 67.320 89.976 112.916 83.508 87.206 62.520 81.055 108.573 6.363 |

96.330 136.954 234.451 308.968 320.839 290.527 316.786 240.070 355.458 317.695 262.040 262.040 373.873 |

548.141 608.481 662.779 649.620 864.260 842.902 884.442 786.666 1.035.141 1.230.270 1.157.955 935.588 1.236.081 |

|||

Source: AFL. 1997-002-4404, Compagnie de Messageries Maritimes Agence de Constantinople, Rapport Général de Service Exercice 1910, 1912, 1921 Chapitre 4, Trafic.

The competition between the Istanbul agency and other steamboat transportation companies differed according to the route. The company competed with the Austrian Lloyd and the Italian companies on the Piraeus route, while on the Odessa route they faced the Russian Steam Navigation and Trading Company; their competitors were the Russian and Khedivate companies on the Syrian route.64 Even though Austrian Lloyd and the Italian companies made regular weekly voyages to Thessaly and Piraeus, the Messageries Maritimes made voyages on this route once every fifteen days.65 In order to increase its revenues, the Istanbul agency decided to organize additional voyages; it also signed an agreement in 1883 with companies that were working on the Thessaly route to fix prices for deck passengers.66

This 1881 agreement, signed with Austrian Lloyd, French Paquet (Compagnie de Navigation Paquet), İdare-i Mahsusa (State Steamboat Management) and the Russian transportation companies with whom the Istanbul agency was competing on the Istanbul, Samsun, Trabzon route, greatly increased the company’s revenues along this route.67 The Messageries Maritimes greatest rival was the Russian transportation company on the Odessa route; this was a route that the company used to ship grain. As the competition along the route drastically decreased the freight revenue, in 1883 the amount of annual voyages was decreased from forty-nine to twenty-three.68 The Istanbul agency was also in competition with the Russian company on the Syrian route. Because the Messageries carried passengers to Syria via İzmir instead of a more direct route, this journey was not attractive to passengers; they preferred a Russian company which made direct voyages once every two weeks.69 Although the freight revenues of the Messageries Maritimes in Istanbul declined in the early 1900s, they started to rise again after 1908.

|

Table 5- 1909-1912 arasında İstanbul’a en fazla un taşıyan yabancı şirketler |

||||

|

Companies |

1909 (Sacks) |

1910 (Sacks) |

1911 (Sacks) |

1912 (Sacks) |

|

Messageries Maritimes Paquet Fraissinet Germans |

250.833 102.104 47.664 42.139 |

130.090 122.704 27.890 5. 461 |

87.818 41.745 5.128 3.975 |

37.750 28.247 500 --- |

Source: AFL. 1997 002 4404, Compagnie de Messageries Maritimes Agence de Constantinople, Rapport Général de Service Exercice 1910, 1912, Chapitre 4, Trafic.

Most of the Istanbul agency’s freight revenue came from passenger transport. While the passengers carried by the company’s steamboats from other regions to Istanbul were mostly deck passengers, two-thirds of the passengers embarking from Istanbul were first and second class cabin passengers.70 The Messageries Maritimes exported silk, silk chrysalis, second class silk, wool, wine, olive oil, tobacco, rags, hardwood, beeswax, salts, aniseed, toads, horn, mohair, leather, chickens, opium, eggs, hazelnuts, beans and other goods from Istanbul. The company also imported flour, cotton, dresses, hats, silk, oil, shoes, fabric scraps, perfume, hardware, alcoholic beverages, sugar, tea, coffee, building materials, nails, bolts, cutlery, porcelain and tiles.71 A large portion of these products were procured from Marmara and Mudanya. Starting in 1902, with the establishment of direct but irregular commercial voyages, firstly between Mudanya and Hamburg, and later between Le Havre and northern European harbor cities, the steamboats of the Messageries Maritimes started to make voyages at irregular intervals to Mudanya.72

As the most populous city in the Ottoman State, Istanbul’s commerce was based more on import. Istanbul’s need for food was met by the Rumelian and Anatolian railroads; however, with regulations that were introduced in different periods in order to equalize internal and external custom tariffs, the food requirements started to be met more easily and cheaply via sea transportation.73

|

Table 6- Post carried from Istanbul by the postal delivery companies between 1906 and 1912 |

||||

|

Year |

Messageries (Parcels) |

Lloyd (Parcels) |

Ottoman Company (Parcels) |

German Company (Parcels) |

|

1906 1907 1908 1909 1910 1911 1912 |

1.918 1.863 1.520 1.074 2.106 1.723 1.744 |

- 505 843 708 1.076 628 1.217 |

- 309 957 1.022 1.190 781 676 |

1.445 1.216 1.975 1.174 951 1.557 - |

Source: AFL. 1997 002 4404, Compagnie de Messageries Maritimes Agence de Constantinople, Rapport Général de Service Exercice 1910, 1911, 1912, Chapitre 4, Trafic.

The Messageries Maritimes was one of the leading companies in the transportation of food products like flour and livestock to Istanbul. The company’s steamboats procured the grain they transported to Istanbul from Russian or Danube ports or sometimes from Mersin, İskenderun (grain from Konya) or the Marseille ports. For this reason, products that were declared as import freight by the agency were sometimes bought from abroad, or from different provinces.74 The most important reason why Istanbul imported flour and not grain was the high cost of transporting and storing the grain, purchased at a reasonable price, which was sent to Istanbul from distant regions. For example, at the start of the 1900s, one kg of wheat could be transported to Istanbul from Constanta at eight kuruş and from the steamboat to the mill at twelve kuruş. Because of these prices, the importation of flour was more attractive.75 The transport of processed flour by the Istanbul agency of the Messageries Maritimes increased significantly after 1908. The need for flour in Istanbul increased to such an extent that almost all of sea transportation companies started to transport flour after 1908.76 The amount of flour carried by the companies which played an important role in satisfying Istanbul’s need between 1909 and 1912 can be seen in Table 5.

Another commercial item that made up a significant share of the company’s Istanbul imports was cattle. Their steamboats carried 3,979 cattle to Istanbul in 1909, 5,569 in 1910, 2,634 in 1911 and 4,535 in 1912.77 Messageries Maritimes also took revenue from items other than passengers and commodities.78 The amount of post shipped by the Istanbul agency was another important source of revenue for the company. Post carried by the four large steamboat transportation companies that were in competition for postal delivery in Istanbul between the years of 1906 and 1912 can be seen in Table 6.

The post revenues of the Messageries Maritimes were 309,000 francs in 1908, 368,000 francs in 1909, 477,000 francs in 1910, 601,650 francs in 1911, and 814,000 francs in 1912.79 In addition, the agency earned income from the debarkation of passengers and commodities, and benefited from the exchange rate difference; however, they had numerous expenses that had to be taken account of, such as coal, traffic, hospitals, lighting, repairs, mooring tax, worker and bargeman salaries, and payments to middlemen for the supply of passengers and commodities.80 Armenian merchants like the Kassapian Brothers, the Gülbenkyan Brothers, Essefian, Uncıyan, Karagözyan, Mazlumiyan, Arslanian, Telfelyan and Basmacıyan provided the company with passengers and commodities.81

The company’s Istanbul-based routes were divided into two parts: postal and trade. These routes were designated sometimes according to the political interests of France, while at other times they were designated according to the economic interests of the Messageries Maritimes. Due to this variety of interests, the passenger and commodity revenues of the company on Istanbul-based routes showed huge fluctuation while it operated from the Istanbul harbor between 1852 and 1913. Because Messageries Maritimes was also France’s economic representative in the eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea, it campaigned for influence in Istanbul and its hinterland to ensure the commercial interests of France.

FOOTNOTES

1 W. Müller-Weiener, Bizans’tan Osmanlı’ya İstanbul Limanı, tr. Erol Özbek, Istanbul: Tarih Vakfı Yurt yayınları, 2003, pp. 94-95.

2 Moniteur Universel, 24 Mars 1835, p. 599; Archive de L’Assaciation French Lines (AFL.), 1997 002 5015, Les 75 Ans d’Existence des Messageries Maritimes; H. Grout, Les Services Maritimes Postaux en France, Paris: V. Giard & E. Brière, 1908, pp. 20-22; P. Bois, Le Grand Siècle des Messageries Maritimes, Marseille: Chambre de commerce et d’industrie de Marseille, 1992, vol. 7, p. 163.

3 Şevket Pamuk, Osmanlıdan Cumhuriyete Küreselleçme, İktisat Politikaları ve Büyüme, Istanbul Türkiye Iş Bankasi Kultur Yayınları, 2007, pp. 29-31.

4 M. Angelo Titmarsh, Notes of a Journey from Cornhill to Cairo by Way of Lisbon, Athens, Constantinople and Jerusalem, New York: Putnam, 1846, pp. 58-59.

5 Grout, Les Services Maritimes, pp. 21-23.

6 R. Caty and E. Richard, Armateurs Marseillais au XIXe Siècle, Marseille: Chambre de commerce et d’industrie de Marseille, 1986, vol. 1, pp. 27-28.

7 BOA, DMA, Şura-yı Bahriye (Naval Council), 4/78A, February 21, 1847.

8 Paul Bois, Histoire du Commerce et de L’Industrie de Marseille, XIX-XXe. Siècles, Armements Marseillais Compagnies de Navigation et Navires à Vapeur (1831-1988), Marseille: Chambre de commerce et de l’industrie de Marseille, 1988, vol. 2, p. 63; H. Giraud, Les Origines et l’évolution d e la navigation à vapeur a Marseille (1829-1900), Marseille: Société anonyme du sémaphore de Marseille, 1929, p. 37.

9 Bois, Le Grand Siècle, vol. 7, p. 13; Bois, Histoire du Commerce, vol. 2, p. 63.

10 Marie-Françoise Berneron-Couvenhes, Les Messageries: l’Essor d’Une Grande Compagnie de Navigation Française, 1851-1894, Pups, Paris: Presses de l’université Paris-Sorbonne, 2007, p. 58; Bois, Histoire du Commerce, vol. 2, p. 63; Giraud, Les Origines et l’évolution, p. 37.

11 M. Louis Girard, “Les Grandes Compagnies Maritimes sous le Second Empire”, Les Origines de la Navigation à Vapeur, ed. Michel Mollat, Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 1970, p. 107.

12 Bois, Histoire du Commerce, vol. 2, p. 63.

13 R. Musnier, Les Messageries Nationales, Paris 1947, pp. 98-100; Roger Carour, Sur Les Routes de la Mer avec Les Messageries Maritimes, ed. A. Bonne, Paris: A. Bonne, 1968, p. 22; Giraud, Les Origines et l’évolution, p. 46.

14 In official Ottoman records, the name of the company is usually recorded as Mesajeri Maritim Kumpanyası (Messageries Maritimes Company) or Mesajeri İmperyal Kumpanyası (Messageries Imperial Company).

15 AFL. 1997 002 5242, Compagnie des Services Messageries Maritimes des Nationales, Convention du 28 Février 1851, p. 42; Moniteur Universel, 17 Juin 1851, Seances des 12, 14, 16, pp. VIII-IX.

16 Guide des Services Maritimes des Messageries Imperiales Dans La Méditerranée, Marseille: Impression à l’identique de l’édition d’origine, 1856, p. 6.

17 AFL. 1997-002-4404, Compagnie de Messageries Maritimes Agence de Constantinople, Rapport Général de Service Exercice 1881-1883, Chapitre 1, Personnel.

18 AFL. 1997-002-4404, Compagnie de Messageries Maritimes Agence de Constantinople, Rapport Général de Service Exercice 1907, 1909, 1910, 1911, 1912, Chapitre 1, Personnel.

19 Bois, Le Grand siècle des messageries maritimes, pp. 162-166.

20 AFL. 1997 002 5199, Assemblée Générale du 28 Mai 1853, p. 16.

21 In the 1850s, the tonnage of the company’s steamboats were 1,200; in the 1860s the tonnage was 1,500 and 2,600 in the 1870s. In the 1880s the tonnage went up to 3,400 and 5,000 in the 1890s and at the beginning of the 1900s. The steamboats produced in the early years used 160 hp, in 1857 this increased to 800 hp; in the 1860s the horsepower was 1,600 and 2,900 hp in the 1870s, 4,000 hp in the 1880s, 7,000 hp in the 1890s, and 7,200 hp in the 1900s. (AFL. 1997 002 5199, Assemblée Générale du 28 Mai 1853, pp. 4-5; AFL. 1997 002 5199, Assemblée Générale du 31 Mai 1864 p. 7; AFL. 1997 002 5200, Assemblée Générale du 28 Mai 1897, p. 10; AFL. 1997 002 5200, Assemblée Générale du 25 Mai 1908, p. 11).

22 AFL. 1997 002 4857, Compagnie des Services Messageries Maritimes des National, Convention du 28 Février 1851, pp. 1-2.

23 AFL. 1997 002 5242, Compagnie des Services Messageries Maritimes des National, Convention du 28 Février 1851, p. 5; Moniteur Universel, Seances des 12, 14, 16, p. VIII-IX.

24 Bois, Le Grand siècle des messageries maritimes, pp. 162-163.

25 AFL. 1997 002 5242, Compagnie Services Maritimes des Messageries Imperiales, Convention Pour l’Extension des Services Postaux, Le 25 Février 1854, p. 3; AFL. 1997 002 5242, Convention du 13 Juin 1854.

26 AFL. 1997 002 5242, Compagnie Services Maritimes des Messageries Imperiales, Convention Pour l’Extension des Services Postaux, Le 25 Février 1854, p. 3.

27 AFL. 1997 002 5242, Convention du 31 Mars 1855, pp. 2-6.

28 AFL. 1997 002 4857, Convention du 28 Février 1854.

29 AFL. 1997 002 4857, Convention du 28 Février 1854.

30 AFL. 1997 002 5199, Assemblée Générale du 31 Mai 1857, pp. 33-36; AFL. 1997 002 5199, Assemblée Générale du 31 Mai 1856, p. 38.

31 AFL. 1997 002 5199, Assemblée Générale du 31 Mai 1857, pp. 33-36; AFL. 1997 002 5199, Assemblée Générale du 31 Mai 1856, p. 38.

32 BOA, HR.MKT, 136/17 (January 9, 1856).

33 BOA, HR.MKT, 136/17 (January 17, 1856); BOA, İ.DH, 376/24867 (April 17, 1857).

34 BOA, ŞD, 567/6 (May 25, 1885).

35 AFL. 1997 002 5242, Compagnie Services Maritimes des Messageries Imperiales Convention pour l’Organisation des Services Posteaux dans la Mer Noir (Ligne du Danube et de Trebizonde) Modificative de la Convention du 28 Nov. 1854, p. 1; Commandant Lanfant, Historique de la Flotte des Messageries maritimes-1851-1975, Cholet: Hérault, 1997, p. 20.

36 R. C. Cervati, Guide horaire général international pour le voyageur en orient, Constantinople, Paris: Cervati et Ce., 1909, pp. 245-255.

37 BOA, HR.TO, 319/9 (dated July 12, 1856, the letter writen by Messageries representative Jules Girette to the Minister of Foreign Affairs Fuad Pasha).

38 AFL. 1997 002 5199 Assemblée Générale du 28 Mai 1857, p. 12.

39 AFL. 1997 002 5242, Compagnie Services Maritimes des Messageries Imperiales Convention pour l’Organisation des Services Posteaux dans la Mer Noir (Ligne du Danube et de Trebizonde) Modificative de la Convention du 28 Nov. 1854, p. 4.

40 AFL. 1997 002 5199, Assemblée Générale des Actionnaires, du 5 Novembre 1857, pp. 7-9; Annales du Commerce Exterieur Turquie, Faits Commerciaux, N° 12, 1844-1859, Librairie Administrative de l’Aul Dupont, Paris 1860, pp. 12-13.

41 BOA. HR.MKT, 198/8 (July 18, 1857).

42 AFL. 1997 002 5199, Assemblée Générale du 31 Mai 1857, p. 11; Adolphe Joanne-Emile Isambert, Itinéraire de L’Orient, Paris: Librairie de L. Hachette, 1861, p. 353.

43 AFL. 1997 002 5199, Assemblée Générale du 31 Mai 1859, p. 14; AFL. 1997 002 5199, Assemblée Générale du 28 Mai 1857, p. 25.

44 AFL. 1997 002 5199, Assemblée Générale du 3 Juin 1861, pp. 6-7.

45 Journal Officiel, 8 Aout 1875, Seance du 23 Juillet 1875, p. 6521; AFL. 1997 002 5200, Assemblée Générale du 27 Mai 1876, pp. 14-15.

46 AFL. 1997 002 5200, Assemblée Générale du 27 Mai 1876, pp. 14-15.

47 Journal Officiel, 8 Aout 1875, Seance du 23 Juillet 1875, p. 6521.

48 AFL. 1997 002 5200, Assemblée Générale du 31 Mai 1890, p. 14; Journal Officiel, 30th of January 1881, pp. 529-530.

49 Carour, Les Routes de la Mer avec Les Messageries Maritimes, pp. 159-160.

50 Couvenhes, Les Messageries: l’Essor d’Une Grande Compagnie de Navigation Française, pp. 481-485.

51 AFL. 1997-002-4404, Compagnie de Messageries Maritimes Agence de Constantinople, Rapport Général de Service Exercice 1882, 1883, Chapitre 4, Trafic.

52 R. Thery, Les Services Contractuels des Messageries Maritimes Devant la Crise Mondiale, Paris 1936, p. 12; Bois, Le Grand siècle des messageries maritimes, p. 62.

53 Ali Akyıldız, Anka’nın Sonbaharı [Fall of the Phoenix] , Istanbul 2005, pp. 107-146; Vahdettin Engin, Rumeli Demiryolları Istanbul: Eren Yayıncılık, 1993, pp. 207-208; P. Fesch, Abdulhamid’in Son Günlerinde İstanbul, tr. Erol Üyepazarcı, Istanbul: Pera Turizm ve Ticaret, 1999, pp. 513-515.

54 AFL. 1997 002 5200, Assemblée Générale Ordinaire & Extraordinaire du 31 Mai 1887, p. 22.

55 “Ministère du Commerce, de l’industrie et des colonies”, Bulletin Consulaire Français Recueil des Rapports Commerciaux, Par les Agents Diplomatique et Consulaires de Francse à L’étranger, 1890, vol. 20, 2. Semestre 1890, p. 323.

56 Journal Officiel, 8 Juillet 1887, Assemblée Nationale, seance du 1 Juillet 1886, Annexe 996; Bulletin des Lois de la République Française, 1888, XII. Serie, Deuxieme Semestre de 1887, p. 158.

57 AFL. 1997 002 5200, Assemblée Générale des Actionnaires du 31 Mai 1892, p. 8; Journal Officiel, 8 Juillet 1887, Assemblée Nationale, seance du 1 Juillet 1886, Annexe 996.

58 AFL. 1997 002 5200, Assemblée Générale du 31 Mai 1890, p. 22.

59 AFL. 1997 002 5200, Assemblée Générale du 31 Mai 1891, p. 23.

60 Carour, Les Routes de la Mer avec Les Messageries Maritimes, p. 146.

61 AFL. 1997 002 5200, Assemblée Générale des Actionnaires du 31 Mai 1895, p. 13; AFL. 1997 002 5200, Assemblée Générale des Actionnaires du 31 Mai 1897, p. 15; Bulletin des Lois de la Republique Française, 1894, II. Serie, Dexieme Semestre de 1895, p. 189; Chambre de Commerce et D’Industrie, 1re Année, N° 54, Paris 1894, pp. 3-4.

62 Bulletin des Lois de la Republique Française (1894), II. Serie, Dexieme Semestre de 1895, p. 190.

63 Bulletin des Lois de la Republique Française, (1894), II. Serie, Dexieme Semestre de 1895, p. 193; AFL. 1997 002 5200, Assemblée Générale des Actionnaires du 28 Mai 1897, pp. 9-12.

64 AFL. 1997 002 4404, Compagnie de Messageries Maritimes Agence de Constantinople, Rapport Général de Service Exercice 1882, Chapitre 4, Trafic.

65 AFL. 1997 002 4404, Compagnie de Messageries Maritimes Agence de Constantinople, Rapport Général de Service Exercice 1881, 1882, Chapitre 4, Trafic.

66 AFL. 1997 002 4404, Compagnie de Messageries Maritimes Agence de Constantinople, Rapport Général de Service Exercice 1883, Chapitre 4, Trafic.

67 AFL. 1997 002 4404, Compagnie de Messageries Maritimes Agence de Constantinople, Rapport Général de Service Exercice 1883, Chapitre 4, Trafic.

68 AFL. 1997 002 4404, Compagnie de Messageries Maritimes Agence de Constantinople, Rapport Général de Service Exercice 1883, Chapitre 4, Trafic.

69 AFL. 1997 002 4404, Compagnie de Messageries Maritimes Agence de Constantinople, Rapport Général de Service Exercice 1882, 1883, Chapitre 4, Trafic.

70 AFL. 1997-002-4404, Compagnie de Messageries Maritimes Agence de Constantinople, Rapport Général de Service Exercice 1910, 1912, Chapitre 4, Trafic.

71 AFL. 1997 002 4404, Compagnie de Messageries Maritimes Agence de Constantinople, Rapport Général de Service Exercice 1910, 1911, Chapitre 4, Trafic; AFL. 1997 002 4404, Compagnie de Messageries Maritimes Agence de Constantinople, Rapport Général de Service Exercice 1910, Chapitre 5, Contentieux.

72 AFL. 1997 002 4404, Compagnie de Messageries Maritimes Agence de Constantinople, Rapport Général de Service Exercice 1904, Chapitre 2, Secretariat; Fesch, Abdulhamid’in Son Günlerinde İstanbul, pp. 543-544.

73 Pamuk, Osmanlı’dan Cumhuriyete Küreselleşme [Globalization from Ottomans to Republic], p. 37.

74 AFL. 1997 002 4404, Compagnie de Messageries Maritimes Agence de Constantinople, Rapport Général de Service Exercice 1907, Chapitre 2, Secrétariat; AFL. 1997 002 4443, Compagnie de Messageries Maritimes Agence de Mersina, Rapport Général de Service Exercice 1887, Chapitre 2, Secrétariat; AFL. 1997 002 4389, Compagnie de Messageries Maritimes Agence d’Alexadrette, Rapport Général de Service Exercice 1882, 1991, 1910, Chapitre 4, Trafic.

75 Liman Mecmuası, 1927, no. 1, pp. 2-3.

76 AFL. 1997 002 4404, Compagnie de Messageries Maritimes Agence de Constantinople, Rapport Général de Service Exercice 1910, Chapitre 2, Secretariat.

77 AFL. 1997 002 4404, Compagnie de Messageries Maritimes Agence de Constantinople, Rapport Général de Service Exercice 1910, 1012, Chapitre 4, Trafic.

78 AFL. 1997 002 4404, Compagnie de Messageries Maritimes Agence de Constantinople, Rapport Général de Service Exercice 1882, 1883, 1910, 1911, 1912, Chapitre 6, Comptabilite.

79 AFL. 1997 002 4404, Compagnie de Messageries Maritimes Agence de Constantinople, Rapport Général de Service Exercice 1910, 1911, 1912, Chapitre 6, Comptabilite.

80 AFL. 1997 002 4404, Compagnie de Messageries Maritimes Agence de Constantinople, Rapport Général de Service Exercice 1910, 1911, 1912, Chapitre 6, Comptabilite.

81 AFL. 1997 002 4404, Compagnie de Messageries Maritimes Agence de Constantinople, Rapport Général de Service Exercice 1911, Chapitre 4, Trafic.