The Bosphorus Bridge, also popularly known as the “First Bridge,” due to its being the first bridge to be constructed over the Bosphorus, is a suspension bridge that connects Asia and Europe via a highway between Ortaköy and Beylerbeyi. The idea of connecting the continents of Asia and Europe with a bridge and enabling an easy journey between the opposite shores has been on the agenda throughout history. As a matter of fact, the story of the construction of the first bridge over the Bosphorus is to some extent mythical. According to Herodotus, known as the father of history, the renowned Persian emperor Darius I had his army pass over the Bosphorus towards Thrace using a floating bridge that had been constructed by Mandrokles of Samos when the latter marched against the Scythians in the first quarter of the sixth century B.C. Mandrokles is believed to have built this bridge by lining and bonding large rafts and boats next to one another. It is known that at this time, this kind of bridge was often used to transfer soldiers to the opposing shore; these bridges were also used during the early period of the Ottoman Empire.

It is known that the idea of building real and permanent bridges over both the Golden Horn and the Bosphorus was brought onto the agenda from time to time. As a matter of fact, it is narrated that the Italian Renaissance artist Michelangelo wanted to build a bridge over the Golden Horn and that Leonardo da Vinci sent a letter to Bayezid II suggesting the construction of a bridge over the Golden Horn or Bosphorus around 1502. After a long time, at the end of the nineteenth century, the idea of connecting the two shores of Bosphorus via a bridge or submerged tunnel came onto the agenda again. S. Preault, a French railway engineer, designed a project regarding the construction of a submerged tunnel between Sarayburnu and Üsküdar (Salacak) in 1891. This project, known as the “Submerged Steel Tunnel,” aimed to create railway transportation via a submerged tunnel. However, the project was abandoned at the drawing phase since it required robust construction technology and funding. Soon after, Uluslararası Boğaz Demiryolu Şirketi (International Bosphorus Railway Company) proposed to build a ring highway encircling Istanbul, with two bridges connecting Asia and Europe.

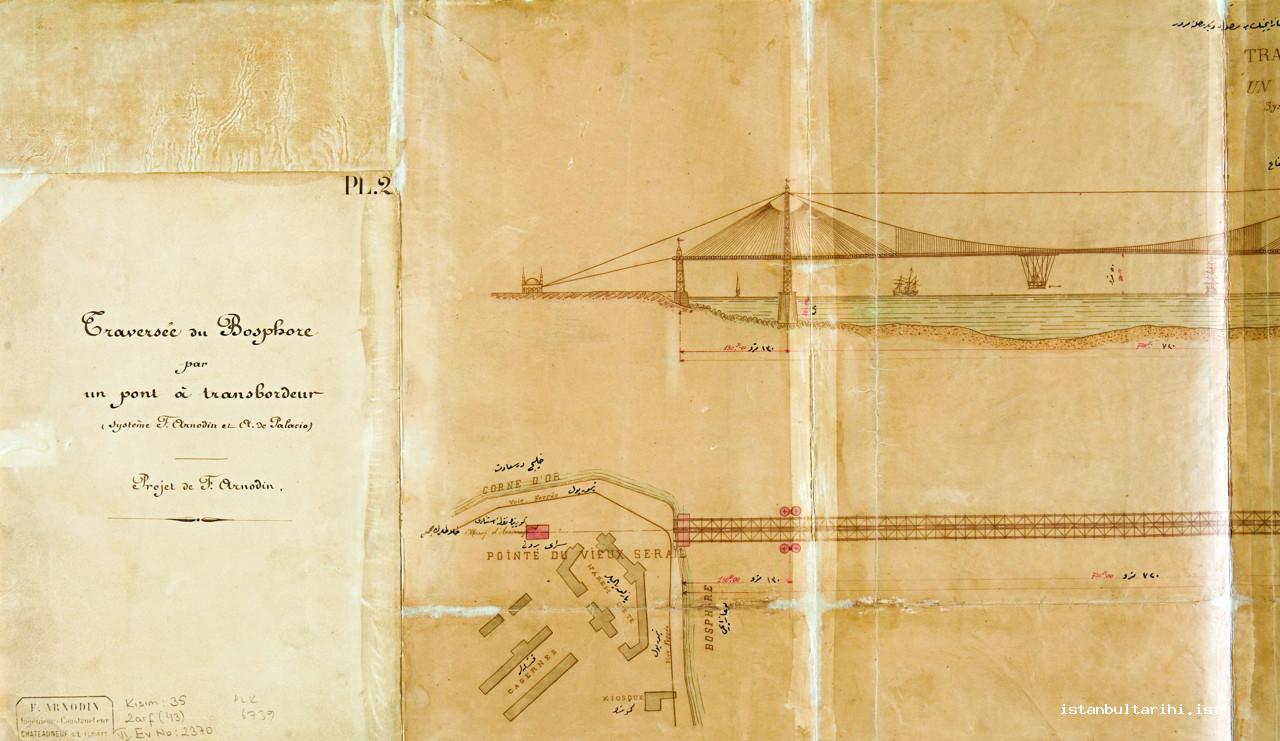

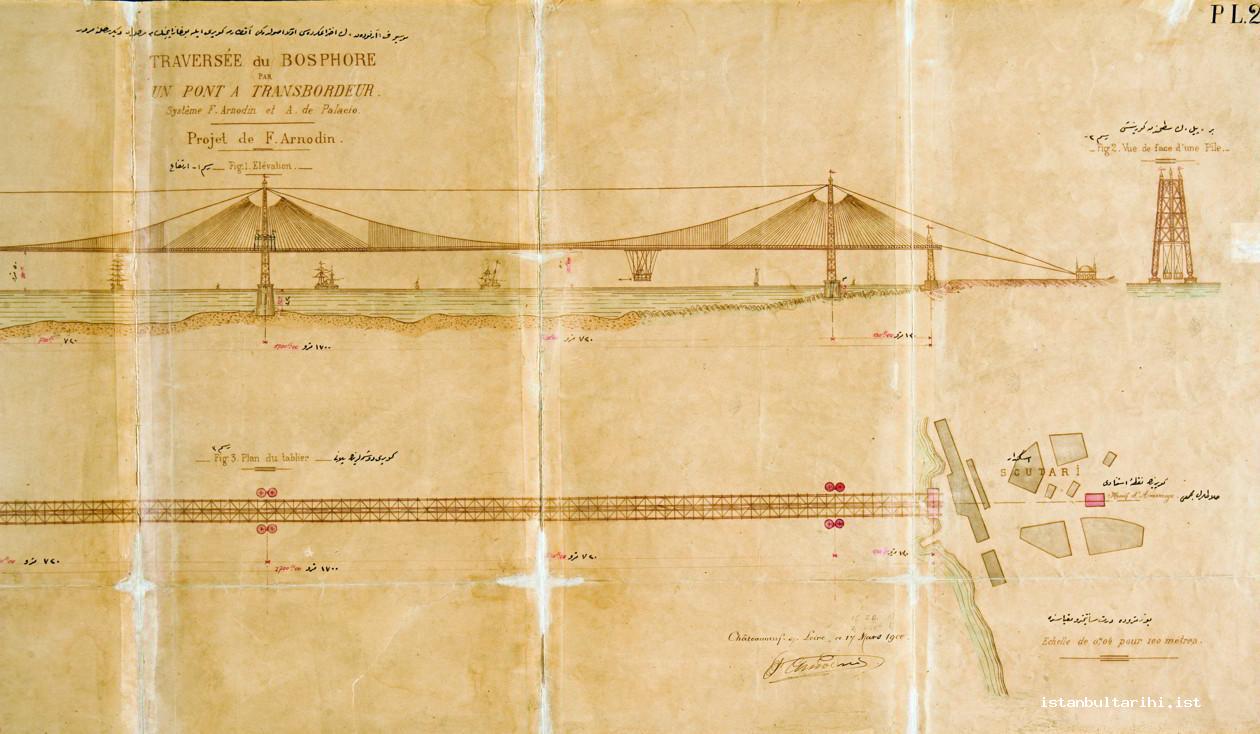

This proposal was put forward by the French engineer and industrialist Ferdinand Arnodin and presented to Abdülhamid II in March 1900. The main purpose of this project was to build a railway system that connected the two continents. To achieve this aim, it was proposed to construct two bridges over the Bosphorus, one between Sarayburnu and Üsküdar and one between Rumelihisarı and Kandilli.

According to this plan, the railway system which ended at Haydarpaşa, stretched from Üsküdar to the European shore; a bridge would be built in this region to connect the railway system on the two shores. The project also envisaged the integration of two regions that had recently become prominent; Bostancı, on the Haydarpaşa-İzmit line and Bakırköy on the Istanbul-Edirne line; this was to be done with another bridge built between Rumelihisarı and Kandilli. Thus, uninterrupted transportation between important hubs of the city, such as the Istanbul Historical Peninsula, Galata, Üsküdar and the villages along the Bosphorus could be realized. Another striking element of this project is that Arnodin was able to foresee the future development of Istanbul; he prepared important plans to this end. Nevertheless, Arnodin’s project was not adopted by the Palace.

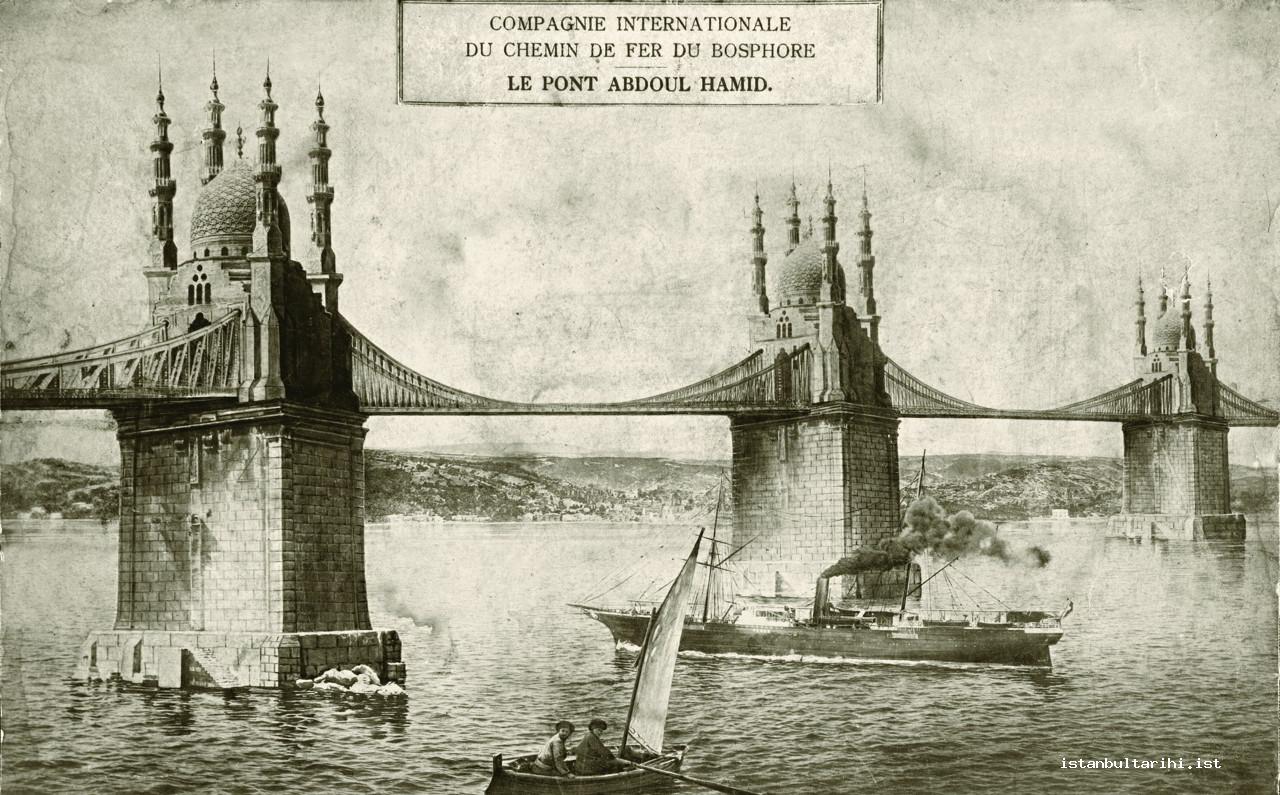

In the same year, after comprehensive planning the Boğaz Demiryolu Şirketi proposed building a bridge between Rumelihisarı and Anadoluhisarı. The bridge, which would carry train, car and pedestrian traffic, was to be called Hamidiye, in keeping with the general traditions of the era. However, this project, which envisaged the construction of a magnificent bridge, was not approved by the sultan either.

Once again, in the era of Abdülhamid II, three American engineers, Frederik E. Strom, Frank T. Lindman and John A. Hilliker proposed a subway project to the palace. For the era, the Tunel-i Bahri (marine tunnel) was a utopian underground railway system; it was designed to operate between Asia and Europe. The plan suggested a tunnel to be constructed between Sarayburnu and Salacak. However, this proposal was also rejected as a flight of fancy. As in subsequent days the Ottoman Empire entered a period of domestic turmoil and wars, the idea of a bridge or a tunnel over the Bosphorus was no longer one of the main topics on the agenda.

The first initiatives in the Republican era regarding the construction of a bridge over the Bosphorus were carried out by the distinguished entrepreneur Nuri Demirağ in 1930s. Demirağ wanted to build a suspension bridge, similar to the Golden Gate Bridge of San Francisco, in cooperation with engineers and experts he invited from the United States. The planned bridge was to be located between Ahırkapı and Salacak. It was to be 25.6 meters in length, 20.72 meters wide and 53.34 meters high.

Separate roads were envisaged for train, tram, car and pedestrian traffic on the bridge. According to the project, the train would switch from Kumkapı and arrive in Haydarpaşa via Doğancılar, thus making it possible to integrate train systems from Europe and Asia. It was projected that the project would be completed within three and half years and cost 11,000,000 liras. Although the project was approved and transferred to the government by Atatürk, the Minister of Public Works Ali Çetinkaya and Prime Minister İsmet İnönü opposed it. Demirağ continued to try to realize this bridge project over the Bosphorus until the 1950s, but was unable to achieve his dream. The fact that the population of the city was not large, and that there was not sufficient traffic to warrant such a bridge which would require a great deal of funding, and differences of opinion with Demirağ all played an important role in this failure.

Although the idea of constructing a bridge over the Bosphorus had been brought forward and failed constantly since the end of the nineteenth century, the idea of connecting Asia and Europe with a bridge never lost its appeal. The construction of a bridge or tunnel over the Bosphorus was one of the main topics of discussion, particularly after the 1950s when Istanbul was developing rapidly and the population had started to grow. For example, the engineer Metin Pusat prepared a project for crossing the Bosphorus via a tunnel in 1950; he announced this project at a press conference. However, his project did not attract a significant public attention. On the other hand, the German Krupp Company commissioned the architect Paul Bonatz, a lecturer at Istanbul Technical University, to conduct a bridge study in 1951. According to this study, the best location for the bridge was Ortaköy-Beylerbeyi; the current location of the bridge. The Krupp Company prepared a project in accordance with this study. However, their work did not bear fruit either.

A committee composed of representatives from the Ministry of Transportation, Municipality of Istanbul, General Directorate of Highways, Directorate of Construction of Railways and Stations, Directorate of Construction and Public Works and Istanbul Technical University carried out studies regarding the construction of a bridge or tunnel over the Bosphorus. Due to the serious dimensions of this project, the committee concluded that this study should be conducted by a qualified company. As a result, the General Directorate of Highways contracted the American De Leuw, Cather and Company on July 8, 1955. The company published its report in May, 1956. This report also designated the Ortaköy-Beylerbeyi line as the best location for the construction of the suspension bridge. The General Directorate of Highways was authorized to select a consulting firm for the construction of the bridge over Bosphorus with a law passed at the Grand National Assembly of Turkey on September 13, 1957; subsequently the bidding process began. A contract was made with the winner, the American D. B. Steinmann Consulting Engineers, on October 24, 1957. The company submitted the project and technical specifications at the beginning of 1960 to commence the bidding. At this time, the German Dyckerhoff und Widmann Company also proposed a different project, suggesting a bridge to be built with a concrete conveyor belt system, this time between Kuzguncuk and Yıldız. However, their proposal was rejected on the basis that a suspension bridge would contribute to the beauty of Bosphorus. The bridge was decided to be built in accordance with the project of D. B. Steinmann Company. The government commenced bidding process and asked for proposals until May 16, 1960. However, just at a time when a bridge could have been built over the Bosphorus and this centuries-long dream would come true, the military coup of May 27, 1960 disrupted the process and the bidding was cancelled.

However, the issue of constructing a bridge over the Bosphorus came to light again with the increase in population that was caused by internal migration, rapid urbanization; added to this increased population, the inadequacy of car ferries for transferring people between the opposing shores played an important role. A new bidding process was begun due to the fact that the earlier projects had been prepared for obsolete technologies and due to the former conditions. On August 31, 1967 the companies who were qualified were asked to prepare projects for a suspension bridge over the Bosphorus and a ring highway. A contract was signed with the company that won the bid, the British Freeman, Fox and Partners Company, on February 8, 1968. The construction tender was awarded to the German consortium Hochtief A. G. and the British Cleveland Bridge and Engineering Company.

The dream of connecting two continents to one another via a bridge, a project that had taken years of consideration and planning, was about to be realized. The foundations of the Bosphorus Bridge were laid on February 20, 1970 at Beylerbeyi. The bridge was officially inaugurated by President Fahri Korutürk on October 29, 1973, a date that marked the fiftieth anniversary of the Republic (Photograph 1). The construction of the Bosphorus Bridge and ring highway, which enabled the connection of the continents of Asia and Europe for the first time, was subjected to significant criticism. Primarily the Chamber of Architects and several other institutions, individuals and politicians did not approve of the construction of a bridge over the Bosphorus. Their criticism was essentially based on the opinion that a bridge to be built over the Bosphorus would seriously destroy the natural and historical silhouette of both Istanbul and the Bosphorus.

The Bosphorus Bridge is located between Ortaköy and Beylerbeyi, with three lanes going from Asia to Europe and three lanes from Europe to Asia for vehicles, and two lanes in each direction for pedestrians. The total length is 1,560 meters, the length between the abutments is 1,073 meters and the height above the sea is sixty-four meters. After May 2, 1974 the bridge was opened to pedestrians for a toll of one lira. However, it was closed in 1978 due to frequent suicide incidents. Vehicles are subject to tolls on the Bosphorus Bridge. Thus, the bridge has been a significant contributor to the economy since the day it was opened. In addition to the financial contributions the bridge has made to the economy, it has been serving the citizens for a variety of social events as well. The Asian and European People’s Marathon, which crosses over the Bosphorus Bridge, began on April 1, 1979; today this event is known as the Intercontinental Istanbul Eurasia Marathon, and draws international participation. The bridge was illuminated on April 22, 2007, offering a spectacle of different coloured lights for the residents of Istanbul and tourists.

It was renamed as 15 Temmuz Şehitler Köprüsü (Bridge of 15 July Martyrs) in the memory of the civilians who were killed there during the coup d’etat attempt on 15 July 2016

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Boğaz Köprüsü Üzerine Mimarlar Odası Görüşü, site and date not available.

Çelik, Zeynep, Değişen İstanbul, Istanbul: Türkiye Ekonomik ve Toplumsal Tarih Vakfı, 1996.

Erer, Tekin, Boğaziçi Köprüsü, Istanbul: Boğaziçi Yayınevi, 1973.

Eyice, Semavi, “II. Beyazıd Devrinde Davet Edilen Batılılar”, BTTD, vol. 4, no. 19 (1969), pp. 23-30.

İlter, İsmet, Boğaz ve Haliç Geçişlerinin Tarihi, Ankara: Karayolları Genel Müdürlüğü, 1988.

Kayserilioğlu, R. Sertaç, Osmanlı’da Ulaşımın Serüveni, II vol., Istanbul: İETT İşletmeleri Genel Müdürlüğü, 2011.

Kuruyazıcı, Hasan, “Boğaziçi Köprüsü”, DBİst.A, vol. 2, pp. 288-289.

Nuri Demirağ’ın Hayat ve Mücadeleleri, Istanbul: Nu. D. Matbaası, 1957.

Sezen, Salih and Ahmet Apaydın, İstanbul’da Ulaşım, Istanbul: İETT İşletmeleri Genel Müdürlüğü, 2012.

Tekeli, İlhan, Kent İçi Ulaşım Yazıları, Istanbul: Tarih Vakfı Yurt Yayınları, 2010.

Yılmaz, Ömer Faruk, “Boğaziçi Tüp Geçit Projeleri”, Yedikıta, no. 13, 2009, pp. 12-15.