Since the dawn of time great states have given importance to communications in keeping with their positions; the aim is to maintain communication systems between the capital and the provinces in a constant active and functioning manner. With a centralist, bureaucratic structure, and possessing vast territories and dominions, the communication systems of the Persian, Roman, Byzantine and Ottoman states are remarkable examples of this. In this article, the historic process that communication underwent in the city of Istanbul will be discussed, dating from its foundation to the collapse of the Ottoman State.

THE ROMAN AND BYZANTINE ERA

From the time that the city of Constantinople was established, communication activities were conducted in a variety of means. This important city was included in the communication system (curcus publicus) that had been established by the Roman Empire, and which was developed by imitating the Persian postal service. Not only did this system connect vast territories of the empire with the center, the advanced road network which Rome had used for military purposes from the fourth century BC also provided official communication for the state (i.e., the emperor and, with a special permit, the Roman elite). There were posts known as civitates on the Roman military routes at which messengers stayed. In addition, there were mutationes (stations) where messengers and horses were changed and there were mansiones (inns) , which hosted messengers and soldiers.

The news that needed to be conveyed was announced by town-criers in the marketplaces of the cities. In addition, news documents with official content, known as Acta Publica or Acta Diurna, were hung on the walls of important buildings around the plaza, thus informing the public about developments.

This Roman communication system was also used in Byzantium. That is, the mansiones and mutationes of Rome could be found here as well. A great variety of orders, official documents and news from high-ranking bureaucrats, in particular, from the emperor, were transmitted to the provinces thanks to this system. The public was also able to benefit from this state-controlled system after the necessary permission had been attained. Expenditure on the buildings and facilities that were part of the communication network were covered by the locals living in the vicinity. This system, which functioned well between the fourth and sixth centuries, later lost its efficiency; private messengers came to prominence in intracity communication during the final era of the Byzantine Empire. In addition to these, important landowners had personal messengers.1

The Byzantines also used high signal towers and hills to communicate with one another within and outside of the city. Based on sight, this system was mostly used along the Tarsus-Constantinople route to warn about Arabian raids that originated from the southeast; reports were given about incoming enemies or potential threats with burning fires and smoke from the signal towers; thanks to this system, reports could be relayed quite rapidly. For instance, information about an attack that occurred near the border could be relayed to Constantinople in a matter of hours. These towers were erected on the European side of Constantinople, at Ahırkapı, and on the Anatolian side, near the Moda Peninsula, the Fenerbahçe Lantern and Kayışdağı. The signal tower at Kayışdağı, next to the Byzantine monastery, used fires to rapidly relay the signals that came from other towers to the Fenerbahçe Tower, while the Fenerbahçe Tower relayed the news onto the Ahırkapı Tower. A military committee was in charge of communication at a lighthouse which was part of the emperor’s palace, known as Kontoskopium; signals sent from furthest places were relayed from tower to tower and reached Kontoskopium. In this way, the Byzantine palace was kept informed of all developments. Because of this, the emperors placed great importance on the tower.2 A communication system that consisted of signal towers was used up until the eleventh century. According to Celal Esat Arseven, this communication system was banned by Michael III, the Drunk, (r. 842-867). Michael III was a great fan of the hippodrome races performed in the Hippodrome. One day bad news was received from the tower and led to confusion during a race; Michael III banned any further communication in this way. The Latins, for example the Genoese and Venetian, established commercial colonies in the city, and used their own messengers and communication networks.

OTTOMAN POSTAL SYSTEM AND ISTANBUL

The Ottoman State, with its political, economic and social structure, was a rich civilization that was established on the geographical and cultural inheritance left by former civilizations; the vast transportation and communication system centered in Istanbul had an effect on the formation of this civilization. When Constantinople was conquered, the communication system, like many other Byzantine institutions, had already lost its efficiency. As a result, the communication system was completely restructured, and once again centered in Istanbul. Official communication in the Ottoman State was, for the most part, carried out by the postal system known as ulak-menzil (messenger-post). There were both military routes and postal routes, most of which followed the same course, spreading throughout Anatolia and culminating in Istanbul. Three main routes (the right, central and left branches), leading to both Anatolia and Rumelia, made up the basis of Ottoman transportation and communication system. The right branch began in Üsküdar, went through Anatolia until Aleppo, Damascus and the Hejaz; the middle branch also started in Üsküdar, went through south-eastern Anatolia, going as far as the Persian Gulf via Kirkuk and Baghdad. The left branch followed the route of the middle branch, and then went through Erzurum to Kars and Tabriz. On the Rumelian side, the right branch stretched towards Istanbul, Kırklareli, Babadağı, İsakçı, Akkirman, Özü and the Crimea, while the middle branch stretched towards Istanbul, Edirne, Plovdiv, Sofia, Nis and Belgrade; the left branch headed towards Istanbul, Tekirdağ, Komotini, Kavala, Thessaloniki, and then through Larissa to Durres.3

There were resting places on route, first known as derbent, and then as menzil (posts), which provided security for the region and allowed the messengers to change horses, find lodging, food and rest. The new communication system, under the total control and at the service of the state, was known as the ulak-menzil system, and was established during the era of Lütfi Pasha, one of the grand viziers of Süleyman I, the Magnificent.4 In the ulak-menzil system roads stretched across Anatolia and Rumelia and spread over vast areas; there were menzilhane (stations) located in suitable places where messengers and the army could rest. The menzilhane were used to communicate with Istanbul and also served as post offices.

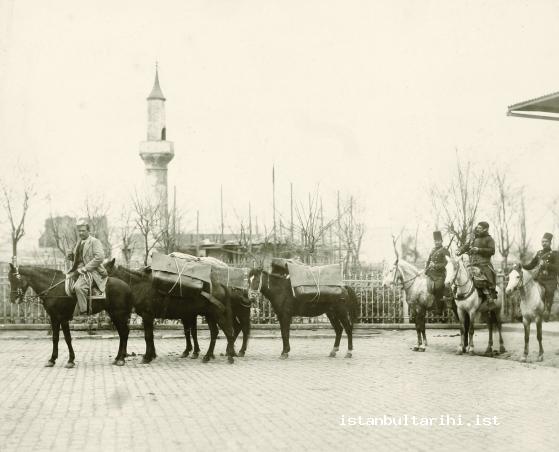

Officials who carried news and orders, for example ulak5 (messengers), Tatars and sergeants benefitted from the stations. The ulak, who were selected for physical stamina and trustworthiness, ensured the rapid official communication of the state between the capital and the countryside. Mounted messengers were at first chosen from the Crimean Tatars, and they were equipped with their own special uniforms and headwear. The Tatar Ağa was the chief of the post Tatars. Moreover, mounted sergeants, part of the sergeants’ organization, acted as the sultan’s runners, providing the transmission of the royal decrees and secret communications of sultans. Abdulhamid I organized menzilhanes and reorganized the Tatar messengers under the order of the Tataran Ocağı in 1775, thus introducing control and discipline to this institution. 228 Tatars were serving in 1785, both in Istanbul and the countryside.6 Generally referred to as ulak, the Tatars served the sultan, the grand vizier, viziers and other high-ranking administrators and bureaucrats; in other words, they were active in official communication, but not responsible for communication between ordinary people. Merchants and the people in Istanbul used private messengers, travelling merchants, caravaneers and sailors, all of whom worked for a fee, to carry out their communication. As the official communication establishment declined, the number of private messengers increased.

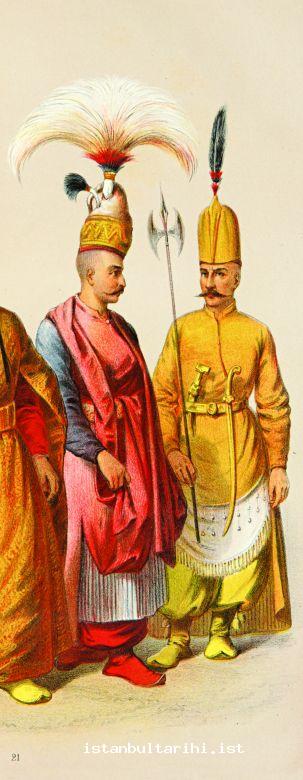

Existing from the fifteenth century onwards, the duty of the peyks was mostly concerned with intracity communication. The term peyk was used by the Ottomans to refer to a foot-messenger. Peyks were a part of the palace organization and usually relayed urgent messages and decrees from the sultan to the relevant parties in the city;7 in addition, they accompanied the sultan, running in front of his horse, as well as reporting the return of the pilgrims and the locations at which they had arrived during the pilgrimage season. They were led by the peykbaşı; over time, their numbers increased to 150. As they were stationed beside the sultan, the peyks wore ornamented and magnificent uniforms;8 they wore silver-gilt embroidered garments, silver-jeweled sashes, golden daggers, held tabars (poleaxes) in their hands, and sported golden crowns and hoods on their heads. In short, their appearance made it easy to understand that they were affiliated with the palace. Athletic, slim, agile, resilient and fast-footed people were selected for this post. As they could be required to run for hours, they were in constant training; to maintain their energy, they consumed almonds and sweets. They could cover the distance between Istanbul and Edirne, a distance of 156 kilometers, in 24 hours. The peyks were members of the Peykân-ı Hassa Corps, and the peykhâne (barracks) were located in the vicinity of the Blue Mosque; this location is still referred to by the same name. The organization of the peyks was abolished in May, 1829.9

In Istanbul, important notices, information, news, reports and messages were announced by town-criers; the state also used people who had influence in society, for example, imams, preachers, prayer-leaders and sheikhs, to promulgate information. Mosques, tekkes (dervish lodge) and coffeehouses in Istanbul were also important sources for people to attain news.

ORGANIZED POSTAL SERVICES IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

Increased economic and commercial activity in the period which began with the Industrial Revolution in Europe caused a change in the means and methods of communication. This process, during which long-range commercial relationships were intensified, sped up communication and directly affected the Ottoman State. With the spread of railroads and the telegraph, the perception of time also changed, creating an impact on economic and political life.

The Foundation of an Organized Postal Order

Mahmud II (r. 1808-1839) wanted to reorganize the state infrastructure, which was unable to meet the requirements of the times, with European-style institutions. First of all, he attempted to establish a centralized system. The sultan, thinking to use means of communication to inform the public about the reforms he was introducing and those he was planning to carry out, as well as to help implement centralization policies and ensure control over the people, had the first official Turkish newspaper Takvim-i Vekayi published on November of 1831. Published in a variety of languages, ranging from French, Armenian, Greek, Arabic to Persian, this newspaper was published in order “to be the language of the state, to guide the people and to consolidate centralism.” Certain characteristics, such as reporting about all domestic and foreign developments, including official and unofficial advertisements, and that merchants, artisans, individuals and civil servants could subscribe to the newspaper, made the Takvim-i Vekayi an important source of information and news.10

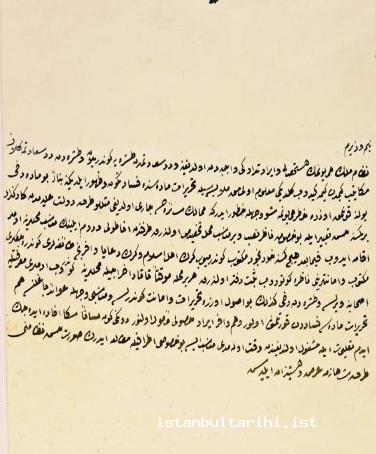

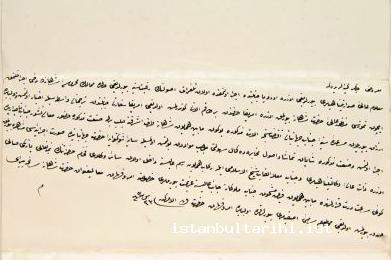

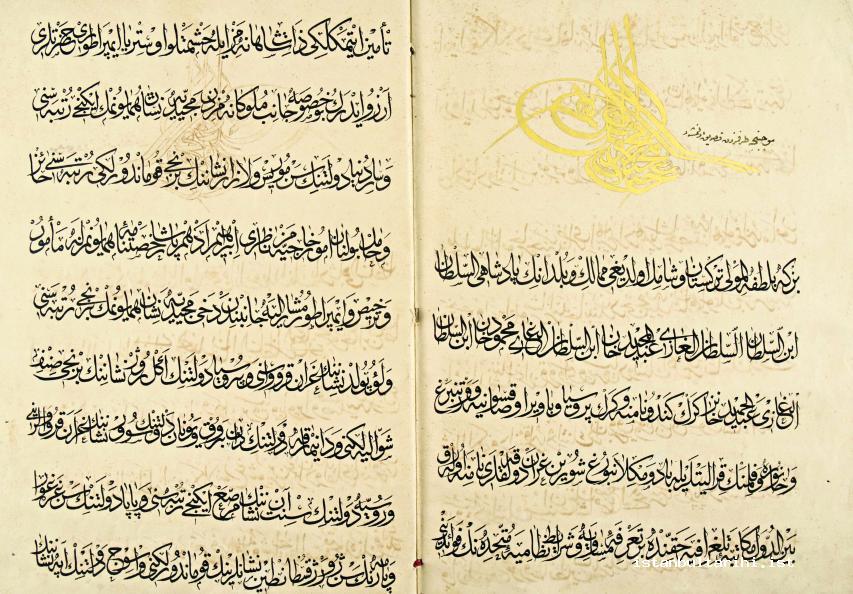

Mahmud II undertook the establishment of the first postal service, in the real sense of the term. This institution was considered to be an important means of support for centralization. In 1833, the sultan informed Grand Vizier Reşid Mehmed Pasha about his ideas and desires on this matter. Considering the lack of order in the circulation of letters and documents, the sultan ordered that a postal service be established, thus allowing for the regulation of postal activities and communication, preventing the loss of mail, providing the Ottoman subjects and foreigner residents with a reliable postal service, as well as being a means for earning revenue from these services. For this purpose, first someone who was familiar with this subject was to be appointed, and then a provincial base of communications was to be organized, thus establishing a strong basis for communications between the center and provinces.11 In keeping with this decision, the 18-hour postal road between Üsküdar and İzmit began to be reconstructed; in October 1834 this route opened with a ceremony that was attended by the sultan.12 Carriages were used for transportation between the postal stations on this route.

The modern postal service which Mahmud II planned to establish was actually only established in the first years of the reign of Abdülmecid, Mahmud II’s son. In these years a postal commission was established; Mustafa Sami Efendi, who was familiar with the relevant applications in Europe, was appointed to direct the postal service on 4 July, 1840. Later, on 9 September, 1840, Ahmed Şükrü Bey was assigned as the first minister of the Postal Service, and on 23 October, 1840, the Postahane-i Amire Nezareti (Postal Service Ministry) was established. Financially it was affiliated with the Treasury and for administrative matters with the Ministry of Commerce. The ministry, according to the austerity measures taken in 1868, was affiliated with the Telegraph Directorate and Ministry of Public Works; on 21st of September 1871, it was bound to Ministry of Internal Affairs as the Posta ve Telgraf Nezareti (Postal and Telegraph Ministry).13

At this time, as in former eras, the post was carried by the Tatars on horse or by carriage; the menzilhanes were put into use for this purpose.14 In this period postal carriages were dispatched about once a week; the postal service attempted to reach even the remotest regions of the country. For example, in 1847 every Monday evening two messengers would be sent to deliver the mail; one would go to Edirne and the other would go to Thessaloniki and Ioannina; they would return on the following Sunday. Every Wednesday evening, five messengers would depart from Istanbul to Anatolia; they would go to İzmir, Alanya, Damascus, Kayseri and Diyarbakır; these messengers would return to Istanbul on the following Sunday. Gradually, the number of days on which messengers were sent was increased and mail was sent more often by sea.15 In the early days of 1841 it was declared that the carriage of mail was the monopoly of the Postal Service Ministry. This precaution was taken due to the fact that some carting companies and tenants, runners, consignees, muleteers, as well as some independent Tatars were providing private postal service. As this situation caused damage for the state, precautions were taken.

The ministry was an institution that not only carried official communications, but it also benefited the people and the merchants. Carrying official documents as well as the people’s mail, the first mail carriage set off for Edirne from Istanbul on 28 October, 1840; on 2 November another one set off for Anatolia. At this time, only paper-based materials, e.g. mails, documents, newspapers and calendars, were carried. The mail was separated into three categories; regular, registered and tahrirat-ı mühimme (official). Starting from January 1841, money and sample trade materials were added to the service; these efforts were met with great satisfaction. However, as the mail could not be carried by carriage, the transportation of money and freight brought many problems. For this reason, the freight service was ended in 1866. However, in 1862, postal transfers were implemented between some centers to reduce the risk of robbery and the difficulty of transportation. The second Posta Nizamname (The Postal Regulation), promulgated in 1871, allowed for the sending of letters, gold and silver coins, jewelry, trade samples and books weighing under 2.5 kg.16

Thus, not only the state, but also the people were provided with inexpensive and organized means of communication. Starting from the 1840s, mail was sent via the sea and in 1863 a coastal postal service was established. Austrian, Russian, English and French steamboat companies were the main operators.17 Beginning from the 1860s, the railroads were included in the postal service; while speeding up the service, the trains also decreased costs.

During the ministry of Yaver Pasha (1868-1871), important changes were made to the central and provincial organization of the Postal Service Ministry. Two general directors worked under the minister; in addition, a Council of Post and Telegraph was established, with high-ranking ministry officials as members. In this period, the Tatar Ağası had 88 Tatars under his command. In addition, there were 8 inspectors, two of whom were stationed in Istanbul, with the other six being in the provinces.18 Despite all these developments, a modern postal service, in the full sense of the term, could only be established during Abdulhamid II’s reign.19 The ministry was reorganized according to the Posta ve Telgraf İdare-i Umumiyyesinin Teşkilât-ı Cedidesine Dair Nizamname (Regulation on the New Order of the Postal Service and Telegraph Ministry), on 5 November, 1876. In this new regulation, troubling aspects of the 1871 regulation were eliminated and the authority and responsibilities of the officials were defined.

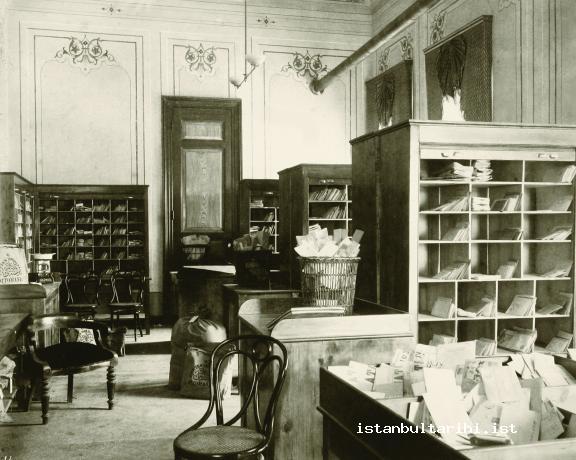

Istanbul Post Offices

Post offices in Istanbul were generally built in neighborhoods where non-Muslims and Europeans resided. The first Ottoman post office went into service in Eminönü, near commercial and transport centers. This post office was opened in a wooden building in the courtyard at the rear of Yenicamii; which was previously used as a Cizyehane (tax office), and was known as Postahane-i Amire (Imperial Post Office). There was an area in front of the building for unloading mail from the provinces. The upper floor of the building, a property belonging to a foundation, housed the Postal Service Ministry, while the lower floor acted as the post office. The tuğra (signature) of Abdülmecid can be seen on the plaque above the entrance to the building, as well as the inscription Postahane-i Amire, written in calligraphy, and the French word Poste. The post office accepted mail only on the day on which it was to be transported and only at certain times of day. When stamps and letterboxes started to be used in 1863, these limitations were abolished. Beginning from 1871, the post office started to accept mail every day but Friday. Two years later the regulation that the Istanbul post office was to be open from sunrise to three hours after sunset was put into effect.20

In earlier years, the minister of the postal service also acted as the director of the Istanbul Post Office. In 1841, the staff of the post office, not including the minister and the director of the post office, consisted of 24 members of staff, 9 officials and 15 Tatars. The sum salary of these personnel was around 18,000 kuruş. Gradually, in parallel with the development of the organization, both the amount of staff and their salaries increased.21 The first Ottoman stamp was printed on 13 January 1863, under the ministry of Çapanzade Agah Efendi.22 This stamp was made by printing and coloring a lithograph printed on cigarette paper in the Darphane-i Amire (Imperial Mint), created by the Ser-sikkegen (Head of the Imperial Mint), Abdülfettah Efendi. Starting from 1865, the star and the crescent pattern was added to postal stamps of different values, all containing the tuğra of Abdülaziz. After 1863, not only was the ministry personnel increased in the headquarters, but the number of post offices in Istanbul also grew. In addition to the Postahane-i Amire (in Sirkeci), post offices were opened in Beşiktaş, Galata, Şehzadebaşı, Sultanahmet, Eyüp, Kasımpaşa, Kadıköy and Üsküdar.23 While the postal stamp made it easier to send documents and mail, it also helped prevent abuses of the system. Once again, on the initiative of Agâh Efendi, postal boxes placed in different areas of Istanbul meant that it was no longer necessary to go to the post office, and, as a result, the amount of mail sent increased.

Adding the telegraph in 1871, the ministry’s name became The Postal Service and Telegraph Ministry; the Postahane-i Amire became the Istanbul Post Office. A new stone building was constructed in 1892, replacing the old building which was unable to answer the increasing needs. Construction stopped a couple of times due to rumors that the building was not safe; this building was not used for a long time. After serving some time as a post office for packages, the building was finally handed over to İş Bankası in the Republican era.24 The Istanbul Post Office started to function at the building that was completed in 1909; it is still housed here. Built between 1905 and 1909, located at Büyük Postahane Caddesi (Great Post Office Avenue) in Eminönü, today the building serves as the Sirkeci Main Post Office. This structure is the work of the architect Vedat Tek, a representative of the First National Architecture era. It is accessed by stairs on the both sides; offices are placed in the area of the corridors that enclose the rectangular main space.25

Another historical post office in the city was the Beyoğlu Telegraph Office. The telegraph office was first set up on Kalekapısı Mektep Street; later it operated in different locations, finally moving to Galatasaray (Post Office of Galatasaray). Establishing a post office in Beyoğlu was mostly about the demographic and social structure. In addition to merchants and bankers who had commercial relationships with Europe, embassies were also here. Serving as the Beyoğlu Telegraph and Postal Center, this post office was mostly concerned with telegraphs, and most of the workers were foreigners who were familiar with European languages.26

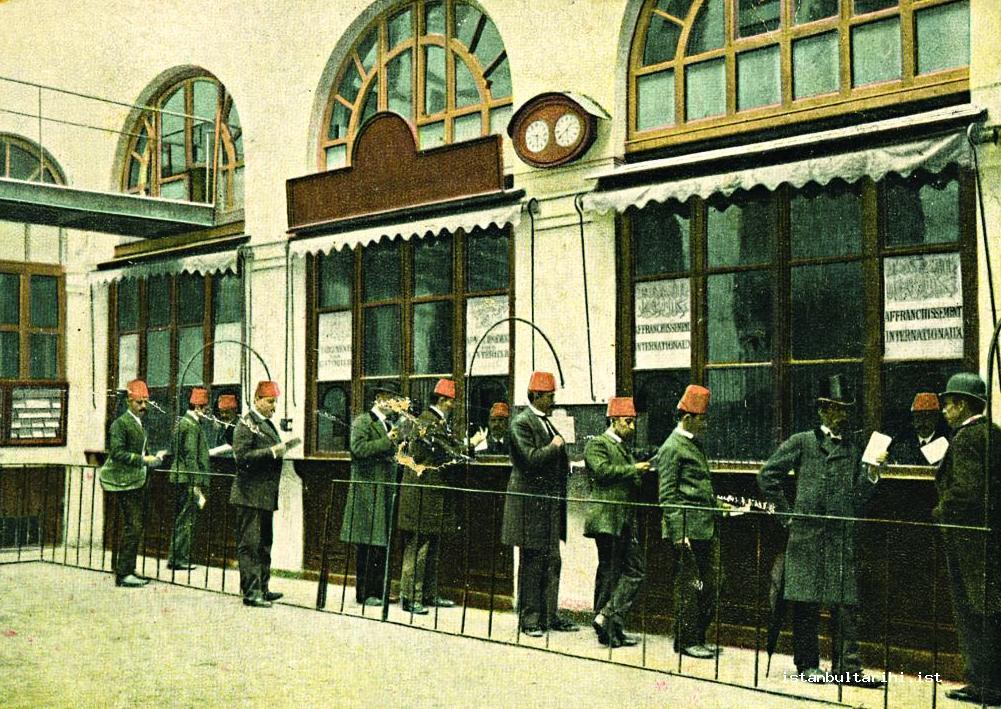

Istanbul Postmen

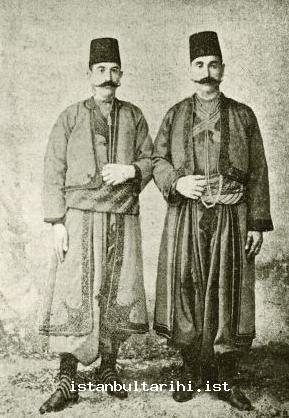

In earlier periods, although Tatars, peyks, messengers and sergeants carried out the function of mail carriers, mail carriers, in today’s sense of the word, only appeared in the second half of the nineteenth century. Mailmen, or as they were called in that period, müvezzi (distributors), carried mail and messages to the relevant addresses. Even after the establishment of the Postal Service Ministry, the Tatars continued to serve. However, their uniforms were simpler than in the previous era. In the 1870s the Tatars earned a salary of 500-600 kuruş. Heading up the Tatars, who resided at Elçi Han and were affiliated with the Tataran Ocağı, was the tatarbaşı; after 1840 this individual was known as the sertatarân or tatarân müdürü. The working principals of the Tatars were defined in accordance with a regulation dated 1871. With the establishment of the ministry, the activities of the Tatars in distributing the mail started to decline and they started to be replaced by mailmen. In 1918, after mail started to become more frequently transported by sea and rail, the Tatars were finally relieved of their duties.

Between 1852 and 1857, the concession for the distribution of the mail was granted to İsmail Pasha as a tax farm (iltizam). İltizams were awarded after bidding, and a certain fee was provided in return for the delivery of the mail. However, this system was later eliminated, as it was not to the benefit of the treasury and as it was very open to abuse.27 Before 1861, the letters came to the post office and after being checked by the director, the addressee had to come and pick up the mail; in other words, the mail was not taken to the recipient. In accordance with a regulation dated September 1861, if the addressee did not come to pick up the letters, then the letter was delivered; thus, we can understand that such a practice of delivery existed.

In August 1865, the concession for the intracity distribution of mail in Istanbul, that is the Birinci Şehir Postası (First City Post Office), was given to Yanyalı Lianos Efendi, in exchange for 365,000 kuruş. The City Post was only responsible for the intracity distribution of mails. This was, actually, a reiteration of the iltizam that had existed between 1852 and 1857. The City Post was quickly organized in accordance with the Dersaadet Şehir Postası Nizamnamesi (Regulation for Istanbul City Post) and started its activities, i.e., the transportation of letter, newspapers and posts between the people of Istanbul, the Princes Islands, and the Bosphorus, in 1865. The number of offices increased as the people in Istanbul showed greater interest. This institution was unable to distribute letters coming from the provinces; however, it was able to accept mail that was sent from Istanbul to the provinces. This system, which meant that the people of Istanbul did not have to go to the post office, was abolished in March 1867, before its time was up; the duty of distributing intracity mail was given to the Directorate of the City Post, which was affiliated with the Postal Service Ministry. In December 1869, the Second City Post started to function under the auspices of the ministry; 14 branches were opened in Beyoğlu, Galata, Sultanmehmet, Beyazıt, Aksaray, Yeniköy, Büyükdere, Tarabya, Ortaköy, Arnavutköy, Kadıköy, Üsküdar and Büyükada.28 In September 1875, the Third City Post was established.29 With the establishment of city posts in Istanbul, the Istanbul ministry staff increased.

According to the new postal law, promulgated after 1882, the fees for delivering letters were abolished. Other forms of mail were distributed by the post office.30 The procedure for sending letters and mail included the following steps: the sender gave the mail to the official, the official recorded the fee, which varied according to the distance, on the mail, the mail was classified according to the place it was to be sent, and it was then given a number. During the reign of Abdulhamid II, mail carriers used a courier bag and wore a uniform jacket and a fez. Due to these aspects, the mail carriers occupied an important place not only in Istanbul’s communication, but also in its folklore.31 The mail service expanded considerably during the reign of Abdulhamid II; while in 1888, 11.5 million pieces of mail were sent; this increased to 24.38 million in 1904.32

Postal Fees and Complaints

Letter and document fees varied according to the distance, weight, and means of transportation. According to the first tariff, an ordinary letter, weighing 3 dirhem (1 dirhem=3.2 grams) cost one lira for the distance of an hour, 4 dirhem was 1.5 lira, and 5 dirhem cost 2 lira; the rates for registered mail was twice as much. In cases where registered mail was lost, compensation of 100 kuruş was to be paid to the sender. However, these fees were valid only for regular post offices; other offices collected the fee from the addressee.33 Mail sent via sea was less expensive. Common complaints made to the postal management included overcharging, the opening of letters and irregular procedures. According to the newspaper Ceride-i Havadis, dated November 1874, merchants’ letters had been opened for a variety of reasons; this contravened European postal regulations, and did nothing but cause people to use the foreign post offices in Istanbul and other cities, thus increasing their revenue.34 The postal management decided not to charge relatives of soldiers for the delivery of letters during the 1877-1878 Russo-Turkish war.35

Foreign Post Offices in Istanbul

The post offices of European states played an important role in the internal and external communications of the Ottoman State. In parallel with capitulations, foreign post offices operated over three centuries, mostly based in Istanbul. Starting from the sixteenth century, Venice, one of the first states to be awarded capitulations due to its commercial connections, employed couriers in trade cities, such as Istanbul, İzmir, Alexandria and Aleppo. Countries that had commercial connections with Istanbul followed suit. Starting from the eighteenth century, the first post offices in the modern sense were constructed by foreign states in Istanbul. The problems with the Ottoman postal system played an important role in the establishment of foreign post offices. Austria led the way in this matter, starting a diplomatic postal service in 1746 and an organized postal service in 1821. A total of 78 post offices, three of which were in Istanbul, were opened in trade centers. Austria’s famous steamboat companies, the Lloyd and Danube steamboat companies, took on an important role in the transportation of mail between Ottoman harbor cities and Europe.36

Between the second half of the eighteenth century and the nineteenth century, Russia, France, England, Italy, Germany and even Greece and the Khedivate of Egypt were granted capitulations to establish post offices and postal management.37 In accordance with these capitulations, the states could use their own currency, stamps and tariffs. Jewelry and other valuables were smuggled into the country using these postal systems. Attempts to shut down the foreign post offices (Levant-Orient posts), which increased their activities with the foundation of the Postal Service Ministry in 1840, were made on the initiative of Âlî Pasha, but this was unsuccessful. The post offices, which were active from the nineteenth century on, were in conflict with the sovereignty and independence of the state, and instrumental in the economic and cultural expansionism of Europe; they are clear examples of the “semi-colonization” of the Ottoman State.38

In 1876 the Beynelmilel İttihad Postaları Merkez-i Umumisi (General Headquarters of International Union of Postal Services) was opened in the Millet Hanı in Galata. Here European experts worked in order to bring foreign post offices under control, to compete with them and to continue communication and postal services with Europe. In 1880, four international post offices were opened in Galata. Even though offices were opened in other major cities, due to the problems experienced in these post offices, foreign postal services continued.39 The foreign postal services were also the means for evrak-ı fesadiyye (publications opposed to the government and the sultan) to enter the state. For example, the Greek post offices in Istanbul were closed in 1868 because they had imported propaganda about the 1866 Crete Riot into the state. At the same time, opposition newspapers and magazines that belonged to Young Turks, who were opposed to the authoritarian administration of Abdulhamid II, were brought to Istanbul and the rest of the country in this way. Even though the foreign post offices were under strict surveillance and control, the entrance of forbidden material could not be prevented. Operations to seize foreign postal services on May 5, 1901 failed due to the reactions of the embassies.

Attempts were made to restrain the activities of foreign postal services in a number of ways; indeed, there were even attempts to close the post offices. Efforts to be competitive by offering reduced prices on bulk stamps and holding raffles among stamp buyers were among the efforts taken to curb the popularity of the foreign postal services. However, in 1904 the foreign postal services offered the same benefits, leading to a decrease in the Ottoman state’s postal revenues. Austrian post offices and postal boxes were destroyed during the boycott that occurred in Istanbul in response to Austria taking advantage of the declaration of the Second Constitutional Period to annex Bosnia-Herzegovina.

The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) also tried to eliminate foreign postal services, or at least tried to make them less effective by enhancing domestic post offices; but they were unsuccessful.40 Finally, foreign postal services were abolished with a law passed on 1 October, 1914, known as the İmtiyazat-ı Ecnebiyyenin Lağvı (Abolishment of Foreign Capitulations); thus, on entry into World War I all capitulations were abolished. During the process to compensate for the increasing workload, a new post office was opened in Galata and the post offices in Pangaltı, Galata, Beşiktaş, Kumkapı, Aksaray and Mahmutpaşa were renovated and extended. In addition, delivery had been sped up with the introduction of automobiles.41 However, when the Ottoman State lost the war, the foreign postal services, in both military and civilian aspects, started to function again. Their position was consolidated by the Treaty of Sèvres. This subject, which was very complicated, would be resolved with the elimination of foreign postal offices in accordance with Article No. 113 of the Treaty of Lausanne at the end of War of Independence.42

THE TELEGRAPH IN ISTANBUL

The telegraph was a means of communication that enabled news and messages to be transmitted over long distances in a short time by the use of codes. Before the advent of the telegraph, it was planned to build communication towers between Istanbul and Silistre (Bulgaria), at one-hour distance from one another; however, this scheme failed to produce anything conclusive around the Bosphorus. After the invention of the telegraph, from 1843 its usage spread through the USA, and western and northern Europe, as well as through Russia. Samuel Morse, who invented the telegraph in 1837, was invited to Istanbul a short time later. During this time, Morse was using the telegraph in Paris. Morse’s partner, Mr. Chamberlain, brought the telegraph machine to Istanbul in 1839. He wanted the invention to be accepted by the Ottoman State and Austria, in other words, he wanted to obtain its patent. However, during trials held in the house of Cyrus Hamlin (the principal of Robert College) there were some problems, and as a result it was decided to have the device inspected in Vienna and then brought back to Istanbul. However, the ship that was carrying Chamberlain and his team sank in the Danube, and with the death of Chamberlain, this initiative failed to bear fruit.43

The second initiative was taken by an American geologist, Lawrence Smith. Smith brought a telegraph machine and installed a telegraph line from Istanbul to a nearby city; the first trial was held before Sultan Abdülmecid at Beylerbeyi Palace on August, 9-10 1847.44 The sultan not only awarded Smith with a medal, but on 22 January 1848, he sent the first telegraph patent from Europe and a medal to Morse. Morse replied to the sultan with a letter of gratitude on 6 January1849.45 Even though the sultan asked Smith to install a line to Edirne, nothing resulted. These developments demonstrate that the Ottoman State was interested in the telegraph before European states were.

The Crimean War and the Use of Telegraph in Istanbul

Immediately after its appearance, the telegraph started to be used in Istanbul and first served as a means of communication during the Crimean War. A vast network of telegraph line was established during the Crimean War (1853-56), a war in which the Ottomans, Britain, and France fought Russia. The first telegraph lines were installed for military purposes; a practical communication device was needed in order to learn what was happening in the war. One of these was the Varna-Istanbul line. Reports on the construction and cost of the telegraph, prepared by English and French entrepreneurs, were inspected by a commission at the Ministry of Internal Affairs; after the sultan gave his approval it was decided to install the telegraph.46 While the French were installing the Istanbul-Edirne-Belgrade and Edirne-Shumen lines, an underwater line was being installed between Varna-Balaklava-Istanbul. Finally, the Istanbul-Edirne line was completed on 19 August 1855 and the Edirne-Shumen line was completed on 6 September 1855;47 both lines were connected to the Varna-Shumen line, which had earlier been installed by the French. On 19 August, M. de la Rue, who had taken on the installation of the line, informed the Ministry of Internal Affairs that the telegraph line had been completed by sending the first telegraph from Edirne to Istanbul.48 This 270 kilometers of line arrived in Edirne after passing through Küçükçekmece, Büyükçekmece, Kumburgaz, Ereğli, Çorlu, Lüleburgaz and Havza.

In late 1856 the sultan approved the installation of another line which was to start from Istanbul and end in Thessaloniki after passing through Tekirdağ, Gelibolu and Serez. One branch of the line was later extended to Austria going through Bitola, Skopje, İlbasan, Shkoder (and later Sarajevo), while the other one extended to Otranto (Italy), passing through Ioannina, Preveza and Vlore. The first telegraph that was sent to Thessaloniki from Istanbul was dated July 7, 1860.49

Telegraph Offices of Istanbul

During the Crimean War the line to Edirne proved insufficient; in September 1855, the British installed an underwater line that stretched from Varna Harbor to the Kilyos shore. A house at Tepebaşı in Beyoğlu functioned as a telegraph office and an overhead line was established to Kilyos. Telegraph officers from the British army started to use this line.50 M. de Lusson was the director of the Telegraph Office in Istanbul at this time. On 10 September 1855, the news that “the allied army had entered Sevastopol” was transmitted to Europe via the Ottoman telegraph system. The British left the Varna-Istanbul underwater line51 to the Ottoman State; this line was used until 1864. However, an overhead line was installed as the underwater line was insufficient and often severed.52 At the same time, the Üsküdar-İzmit line had been completed and a telegraph office was opened in Üsküdar, in January 1859. Nevertheless, with the affiliation of the Telegraph Administration to the Postal Service Ministry, the telegraph office was moved to central Istanbul.

The Ottoman Telegraph Administration was established in 1855, and operated under the Ministry of Internal Affairs until it was merged with the Postal Service Ministry. The first general director of the telegraph was Billurizade Mehmed Efendi, who was appointed to this post in March, 1855. On 21 September 1871 the Telegraph Administration was affiliated with the Postal Service Ministry as an executive precaution and austerity measure, thus making it easier to manage; thus the Postal Service and Telegraph Ministry was formed.53 Istanbul stood at the core of the telegraph network which stretched across the Ottoman State. In 1855, M. de la Rue started to construct a telegraph office across from the Sublime Porte. Built by the famous architect Fossati, the Telgrafhane-i Amire (The Imperial Telegraph Office) was designed as a two-storey building; today, the remains of this building no longer exist, but it stood near Topkapı Palace. A remarkably plain building, it was positioned between the Alay Kiosk and the Soğukçeşme Gate, adjacent to the city walls. Positioned at the start of the route that runs along the city walls to Yedikule, the building was extended with annexes; later, during renovations the telegraph office was torn down.54 The Alay Kiosk was once connected to the Telegraph Office, and the ministers of Postal Service and Telegraph had offices there.

The Galata, Üsküdar and Rumelihisarı telegraph offices were included in the telegraph network. The latter was opened in November1867 was constructed next to Rumelihisarı; it played an important role in fire-fighting. As a result of this development, the amount of staff at the central telegraph administration was increased. In early 1861, there were over 80 personnel working in the Istanbul, Üsküdar and Beyoğlu telegraph offices.55 In addition to these, there were secondary telegraph offices, like Maslak-Emirgan, Tersane-i Âmire (Kasımpaşa), Dolmabahçe Palace and Tokatköy (Beykoz) Çiftlik-i Hümayun. Sending telegraphs that came from the provinces across the Bosphorus was a major problem. Telegraphs that came from Anatolia to the telegraph office in Üsküdar were transmitted to Istanbul via rowboats or along the line that went between Ahırkapı and İhsaniye. However, as this line was often severed by boats and there were not sufficient rowboats, in 1863 a French line, consisting of cutting-edge technology, had to be installed.56

The telegraph not only helped official communication, but brought great ease to the people of Istanbul and merchants. Thus, people gave their support and contributed to the installation of the telegraph lines. To ease communication with Europe for merchants, a telegraph line was installed from Galata to the stock market. The greatest impact of the rapid transition of information via telegraph could be seen in financial and commercial fields. However, there was some abuse and corruption; for example, telegraph lines in Istanbul were distributed by poles and hooks set into the walls of buildings. This resulted in some dishonest people attempting to learn about developments in Europe, particularly about those in the stock market, and thus making an illegal profit. For the most part Europeans, non-Muslims and Levantines profited by spreading false reports57 about the stock market or by learning important information illegally. To prevent such developments, it was decided to construct a building in Yedikule where the lines would link up; here telegraphs would be collected and distributed by mounted messengers.58 In this situation, a telegraph transmitted to Üsküdar telegraph office was transmitted to the base in Yedikule, over Anadoluhisarı-Rumelihisarı and Beyoğlu, and then distributed to the city from there.

Telegraph Schools and the Telegraph Factory

Because the telegraph was fast and reliable, Levantines, bankers, goldsmiths and foreign merchants who lived in Istanbul used it for communication purposes. At first, telegraph officers and technical and administrative personnel were brought from France. However, from 1856 onwards, Turks and Muslims started to take on these duties. In parallel with the increasing number of telegraphic offices, the need for qualified employees also increased. Even though personnel were trained at the Istanbul telegraph center, this was not enough to meet the needs. Thus, the first Fünun-ı Telgrafiyye Mektebi (Telegraph School) was opened in 1860 to train personnel, and to provide theoretical and practical lessons. The location was a wooden house near the Forensic Science building, across from Gülhane Park in Soğukçeşme. However, when this school was closed a short time after opening (probably in 1864), a new school, Mekteb-i Fünun-ı Makineciyan, was opened. In January 1872, the Posta ve Telgraf Mektebi (The Postal and Telegraph School) started to provide education in this field. Some of the graduates were sent to Europe to pursue advanced engineering education. When this school was closed in 1880, the Darüşşafaka Mektebi added classes about telegraphy to its curriculum, and telegraphers were selected from the graduates of this school. Finally, the Telgraf Mekteb-i Âlisi (Telegraph Academy) was opened in January 1910.59 Telegraphers who were educated in this school took on important duties, particularly during World War I. This school continued to operate in the Republican era.

Another problem that appeared with the introduction of the telegraph in the Ottoman State was the procurement of tools and equipment. At first, telegraph equipment was brought from Europe, creating an external dependence; moreover, these imports were expensive. As a result, in May 1869, while Feyzi Bey was the head of the Telegraph directorate, equipment started to be manufactured for the first time. The factory was established in a wooden building that had been a tailor’s; this was located across from Gülhane Park near the Forensic Science building. Here, a hundred telegraph machines were produced in two months. These were less expensive, more practical and sturdier than those that had been imported from Europe. After being relocated in a couple of different places, finally being placed within the city walls, the factory was developed and was able to meet the needs of not only the residents of Istanbul, but the entire country. This successful factory produced more than 5,000 telegraph machines between 1869 and 1918.60

Telegraph Language and Tariffs

One of the problems that occurred when the telegraph began to be used in Istanbul was what language should be used. Telegraphs were first sent in French along all lines; however, this prevented ordinary people in Istanbul from using the technology. A short time after the telegraph came into service, Turkish also started to be used. Owing to the Mustafa Alphabet (Turkish telegraph alphabet), developed by Mustafa Efendi, who had studied this matter, the first telegraph in Turkish, consisting of 128 words, was sent from Edirne to Istanbul on 3 May 1856. Thanks to the new Turkish telegraphic language, the people of Istanbul started to use the telegraph and the number of telegraphs sent increased.61

The tariff for telegraphs was calculated according to word count and the distance that the telegraph was to be sent. From 1855 to 1876, telegraph tariffs were rather expensive. In 1855 the Telegraph Commission prepared the first telegraph tariff; this was valid for ten years. According to this tariff, sending a telegraph of 25 words between Istanbul and Edirne would cost 33 kuruş, while between Istanbul and Shumen it would cost 52 kuruş; between 1862 and 1863, sending a telegraph of 20 words from Istanbul to Ankara would cost 40 kuruş, while it would cost 90 kuruş to send a telegraph between Istanbul and Vlore. According to the 1864 tariffs, out of necessity, the cost of sending telegraphs to Rumelia was decreased and the Istanbul-Vlore tariff was reduced to 45 kuruş. To send a telegraph containing 20 words from Istanbul to Basra, that is one of the longest distances, would cost 277 kuruş. The 1869 and 1873 tariffs were cheaper and more practical.62 The 1876 tariff decreased costs even more. However, sometimes there were disagreements and claims of overcharging, due to miscalculation.63 Official telegraphs were always sent free of charge.

Telegraph and State Administration

A telegraph was sent on 21 January 1865, from Bombay to Baghdad, and from Baghdad to Istanbul, thus connecting India with Istanbul and Istanbul to London; in other words, the East had been connected to the West.64 Istanbul played a pivotal role in this line which stretched from Üsküdar to İzmit, Ankara, Sivas, Diyarbakır, Mosul, Baghdad, Basra, Fav, and India. The telegraph also played a crucial role in state administration. Ottoman administrators, in particular the sultan, could thus communicate with the most remote administrative units swiftly and easily. Abdulhamid II saw the telegraph as a means to realize his centralist policies for both state and provincial administration, as well as a means of modernization and he benefited hugely from it.65

During the reign of Abdulhamid II, telegraph lines were installed in the remotest locations of the Ottoman State. As a result, the capital, Istanbul, was connected to the Aegean islands, Tripolitania, and even Fezzan. During the period in which the telegraph was developed, a direct connection between the people, provincial administrators and the entire country was established. This situation not only spread information, but, despite some negative results, created an effective control mechanism in the provinces. The length of the land line was 23,380 kilometers in 1882, and reached 49,716 kilometers in 1904; the length of the underwater line increased from 610 kilometers to 621 kilometers. In the same period, the number of telegraphs sent increased from 1,000,000 to 3,000,000, and the revenue increased from 39,000,000 kuruş to 89,000,000 kuruş.66 According to the statement of a French telegraph engineer who was working in the Ottoman State: “Turkey was the first state to install lines to places that could not be reached by roads and railways.”67 The fact that telegraph lines could be installed much faster and easier than railways must have played an important role in this development.

The telegraph made important contributions to Abdulhamid II’s regime; however, as can be seen from the declaration of the Second Constitutional Period, it also was instrumental in toppling the regime. Indeed, it was the telegraph that forced the sultan to declare the Second Constitutional Period; this revolutionary movement rapidly spread throughout the territory. In the Second Constitutional Period, which began with the rebellion of Resneli Niyazi Bey, the telegraph operators, who were affiliated with the CUP played important roles in spreading the movement, even providing information about counter measures taken by Abdulhamid II. In this aspect, the Second Constitutional Period was probably “the first revolution in history to be carried out by telegraph.”

The Young Turks used the telegraph extensively in their opposition to Abdulhamid II. The CUP put importance on secrecy and communication in their organization and activities. A member of the famous trio of the CUP, Talat Pasha, worked for the postal service; he attributed the success of the CUP organization to the fact that they had control of the entire postal and telegraph service. He stated: “Nearly all of the major postal and telegraph offices were under our control.”68 During the reign of Abdulhamid II, communication (propaganda and the transmission of newspapers and letters) between CUP members in Turkey with those in Europe was carried out with the assistance of the French post office in Galata and Toustin Pasha. Kara (Zülüflü) Kemal, a member of the CUP, had a large following in Istanbul, and he was able to transmit opposition publications to those people he trusted with ease. He also established the Osmanlı Hürriyet Cemiyeti (Ottoman Freedom Community) in Istanbul. Kara Kemal was the Minister of Provisions during World War I, and during the War of Independence he carried out great services in the transportation of men, weapons and ammunition from Istanbul to Anatolia.

The postal and telegraph organization played an important role in the War of Independence; every movement and communication made by the enemy was followed thanks to this technology. The Karakol Cemiyeti (Sentry Community), which played an important role in the War of Independence, could communicate with Anatolia thanks to the telegraph operators. The posts that were established by the Karakol Cemiyeti were vital in the transportation of men, weapons and ammunition from Istanbul to Anatolia. For this reason, telegraph communication in Istanbul was under strict control. Even though a platoon was positioned at the main post office in Sirkeci to control telegraph communication, such communication was able to be carried out in secrecy and played a significant role in receiving military intelligence. While members of the Karakol Cemiyeti continued to gather intelligence during the Armistice Period, they also ensured communication between members of the National Resistance and Ankara, with the help of Arap İhsan, Hacı Mümtaz and Cevat Bey, the directors of the Istanbul Telegraph Office.69 The Müdafaa-yı Milliye (National Defense) and Felah (Liberation) groups also provided services by sending men and weapons to Anatolia, communicating with Ankara and gathering intelligence.

THE TELEPHONE IN ISTANBUL

Communication gained speed with the spread of telegraph; with the telephone it became even more rapid and practical. Invented in 1876 by Alexander Graham Bell, the telephone broke important ground in the field of communication; it began to be used as a means of communication from 1877 onwards. The first intracity telephone lines were installed in Paris in 1879; in Brussels telephone lines were installed in 1886. While the USA, Great Britain and most European countries had extensive telephone lines by 1900,70 which were partially or completely government-controlled, the introduction of the telephone in the Ottoman State happened relatively late. In fact, a short time after the telephone had been exhibited at the Paris Expo in 1878 it came on the agenda in Istanbul. However, Monsieur Kumbari’s request to attain the privilege of establishing a telephone network for Istanbul and nearby cities was denied in 1879. Other proposals on the same subject were also inconclusive.

The telephone line that was installed in 1881 between the telegraph office in Soğukçeşme and the old wooden post office building in Yenicami, with four telephones, is the first phone line to exist in the Ottoman State. In the same year, a single wire telephone line was set up between the Galata Post Office and the Yenicami Post Office, the Galata head office of the Ottoman Bank and the Yenicami branch, and the Galata Port Authority and Kilyos Rescue Service. However, except for the Galata-Kilyos line, all the other lines were later removed and general use of the telephone was forbidden. Fearing an uprising or assassination attempt, Abdulhamid II forbade the telephone as “an invention that could be used for clandestine undertakings.”71 After 1892, the prohibition became even stricter. In addition, while the sultan refused permission to foreign companies to use and manage the telephone, imports of telephone equipment were also prohibited. This led to protests from European countries.72

The prohibition of the telephone lasted until the Second Constitutional Period. The telephone was reintroduced in 1908, but unlike the telegraph, development of telephone lines was slow. A 50-line switchboard was brought from France and was installed in the newly constructed Sirkeci Main Post Office on 10 May 1909; 45 desk phones with magneto were installed. 28 lines were dedicated to government offices and banks; however, these quickly proved insufficient. As a result, 5 switchboards (one with one hundred lines, two with twenty-five lines, one with fifteen lines, and one with ten lines) were ordered from France, and were installed in the Beyoğlu, Pangaltı, Maliye (Ministry of Finance), and Mebusan (Parliament) Telegraph Offices, respectively. Operating as the Postal Service and Telegraph Ministry from 1871, this institution was later transformed into Postal Service, Telegraph and Telephone Ministry in 1911. As a result of these developments, two regulations were prepared concerning telephone services in 1912 and 1913.

The Postal Service and Telegraph Ministry did not allow individuals to own telephones. In 1911, the Belgium general director of the postal service, Monsieur Sterpin, was given the duty to organize communication and telephone services. At the same time, on 6 April 1911, permission was given for a group of English, American and French investors to establish a company, called Dersaadet Telefon Anonim Şirket-i Osmaniyesi (Ottoman Istanbul Telephone Limited Company); thus, the public use of the telephone was introduced. The company had the concession for building telephone exchanges and networks, ranging from Pendik to Anadolu Kavağı and from Yeşilköy to Rumeli Kavağı; they were also awarded the concession to operate this network for 30 years.73 According to the company’s internal regulations, the telephone exchanges were to be established at three headquarters and other small centers over eighteen months; 15 percent of the revenue would be given to the government once every three months. After ten years no foreign employees were to be employed, except for administrative personnel.74 It was not until 28 February 1914 that the company was given permission to establish Kadıköy, Beyoğlu, and Tahtakale telephone exchanges, with 2,000, 6,400 and 9,600 lines respectively. Later small-scale exchanges using a manual system were added to these earlier exchanges in Kandilli, Paşabahçe, Erenköy, Büyükada, Heybeliada, Kartal, Büyükdere, Tarabya, Bebek, Bakırköy and Yeşilköy.75 General communication by telephone in the city became possible with the establishment of the Silahtarağa Elektrik Fabrikası (Silahtarağa Electric Factory); the failure to satisfy the electricity needs caused this three-year delay.

An indirect impact of the telephone on communication in Istanbul was to be seen in the newspapers of Istanbul. The Tanin newspaper used the telephone to collect news for the first time during the Second Constitutional Period. The first telephone book in Istanbul was prepared in 1914.76 The government seized the Telephone Company at the start of the World War I; however, in 1919, with an end to the war, the concessions were returned to the company. Despite developments in the Second Constitutional Period, it was not possible for the telephone to spread to private houses until the Republican era; rather, the usage of the telephone was limited to governmental institutions. The first telephone call made from Istanbul to another city was to the capital, Ankara, on July 1, 1928.77 With a line from Istanbul to Sofia being installed in October 1931, Istanbul was connected to Europe.

THE PRESS IN ISTANBUL AND COMMUNICATION

Newspapers were another pillar of communication in Istanbul. The first official Turkish newspaper, Takvim-i Vekayi, which began to be published during the reign of Mahmud II, was a source of news and information until the end of the Ottoman State. In 1840, an Englishman, William Churchill published the first private Turkish newspaper, Ceride-i Havadis. While before 1860 there were four Turkish newspapers and magazines in Istanbul with a total circulation varying between 200 and 300, there were more than twenty newspapers and magazines published in Greek, Armenian and French, with a circulation of 2,000. Day by day, the number of newspapers published by non-Muslims, and their circulation increased. In the period between 1860 and 1878, while there were more than 130 new newspapers and magazines published in Istanbul with an estimated total circulation of 10,000, the impact of the press on communication gradually grew. During some important events, the circulation of the newspapers could reach even 20,000.78 Thus, Istanbul took on the attribute of being a center that could mold public opinion.

Published in different periods, newspapers like Tercüman-i Ahval, Tasvir-i Efkar, İbret, Basiret, Muhbir, Sabah, Tercüman-ı Hakikat, İkdam, and Tanin were undeniably important sources of news and information for the people of Istanbul. In 1908, almost half of the newspapers and magazines, that is, 52 out of a total of 120, were published in Istanbul; however, if we compare the activity and circulation of these newspapers, the ratio is closer to 90 percent. During the Second Constitutional Period, the number of newspapers and magazines published in Istanbul, as throughout the state, increased almost 6 or 7 fold. Important Istanbul newspapers from the Armistice Period, like Akşam, Tasvir, Vakit, İleri and Yenigün supported the national resistance.79 Making great contributions to communication, the Istanbul newspapers employed both stationary and mobile reporters in the city. Some of these reporters traveled from district to district, gathering news from the coffeehouses, recording the stories and sending their reports to the newspaper via the fire brigades. Converted into appropriate language, these reports were published in the newspapers as “News from Istanbul.”

FOOTNOTES

1 “Haberleşme” [“Communication”], DBİst.A, vol. 3s, 465-466

2 Monsieur Paspates found the ruins of this tower among the houses behind the Blue Mosque (Celal Esat Arseven, Eski İstanbul, Istanbul: Çelik Gülersoy Vakfı, 1989, p.80).

3 Yusuf Halaçoğlu, Osmanlılarda Ulaşım ve Haberleşme (Menziller), Ankara: PTT Genel Müdürlüğü, 2002, pp. 52-121.

4 Nesimi Yazıcı, “Lütfi Paşa ve Osmanlı Haberleşme Sistemi ile İlgili Görüşleri, Yaptıkları”, İletişim, 1982, vol. 4, p. 225 etc.; Yusuf Halaçoğlu, “Menzil”, DİA, vol. 29, p. 159. For more about the postal system, see: M. Hüdai Şentürk, “Osmanlılarda Haberleşme ve Menzil Teşkilatına Genel Bir Bakış”, Türkler, ed. Hasan Celal Güzel et. al., Ankara: Yeni Türkiye Yayınları, 2002, vol. 14, pp. 446-461. Lütfî Paşa, Tevârih-i Âl-i Osman adlı eserinde, 946/1539 senesi olaylarını anlatırken ulakla ilgili görüşlerine de yer vermiştir. See Lütfî Paşa, Tevârîh-i Âl-i Osmân, Istanbul: Matbaa-i Amire, 1341 [1923], pp. 372-382.

5 This name, which existed in pre-Islamic Turkish states and communities, name means “mounted messenger” or “messenger”. The Orkhon inscriptions and the Divân-ı Lugāti’t-Türk both contain this word, which was introduced from the Mongolian into Caucasian and Balkan languages (İlhan Ayverdi and Ahmet Topaloğlu, Misalli Büyük Türkçe Sözlük, Istanbul: Kubbealtı Neşriyat, 2005, vol. 3, pp. 3233).

6 Geçmişten Günümüze Posta, Ankara: PTT Genel Müdürlüğü, 2007, pp. 171-172.

7 İbrahim Yıldıran, “Osmanlı Saray Teşkilatında Haberci Uzun Mesafe Koşucuları: Peykler”, Osmanlı, ed. Güler Eren, Ankara: Yeni Türkiye Yayınları, 1999, vol. 5, p. 659.

8 Zeynep Tarım Ertuğ, “Peyk” (Osmanlılar), DİA, vol. 34, pp. 263-264.

9 Yıldıran, «Osmanlı Saray Teşkilatında Haberci», p. 659.

10 Nesimi Yazıcı, “Takvîm-i Vekâyi’”, DİA, vol. 39, p. 491.

11 BOA, HH, no. 489/23995 (19 May, 1833 - 29 Zilhicce 1248); İsmail Hami Danişmend, İzahlı Osmanlı Tarihi Kronolojisi, Istanbul: Türkiye Yayınevi, 1971, p. 74.

12 BOA, HH, no. 756/35772 (28 April, 1835 - 29 Zilhicce 1250).

13 Nesimi Yazıcı, “Tanzimat Döneminde Osmanlı Haberleşme Kurumu”, 150. Yılında Tanzimat, prepared by Hakkı Dursun Yıldız, Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu, 1992, pp. 146-146, 207; op.cit., “Posta Nezareti’nin Kuruluşu”, Çağını Yakalayan Osmanlı, ed. Ekmeleddin İhsanoğlu and Mustafa Kaçar, Istanbul: İslam Tarih, Sanat ve Kültür Araştırma Merkezi, 1995, p. 42.

14 “Haberleşme”, DBİst.A, vol.3, p. 466.

15 Nesimi Yazıcı, “Tanzimat Döneminde Osmanlı Posta Örgütü”, TCTA, vol. 4, p. 1645.

16 Mübahat S. Kütükoğlu, «Osmanlı İktisadi Yapısı», Osmanlı Devlet Tarihi, ed. Ekmeleddin İhsanoğlu, Istanbul: Feza Gazetecilik, 1999, p. 602.

17 Kütükoğlu, «Osmanlı İktisadi Yapısı», pp. 602-603.

18 Yazıcı, “Tanzimat Döneminde Osmanlı Posta Örgütü”, p. 1640; Geçmişten Günümüze Posta, p. 154.

19 Yazıcı, “Tanzimat Döneminde Osmanlı Posta Örgütü”, pp. 1641-1642.

20 Geçmişten Günümüze Posta, pp. 162-163.

21 Yazıcı, “Tanzimat Döneminde Osmanlı Haberleşme Kurumu”, p. 1638.

22 Yazıcı, “Tanzimat Döneminde Osmanlı Haberleşme Kurumu”, p. 167.

23 Yazıcı, “Tanzimat Döneminde Osmanlı Haberleşme Kurumu”, pp. 150-151.

24 R. Sertaç Kayserilioğlu and Cemal Kuntay, “Postahaneler”, DBİst.A, vol. 6, p. 281.

25 Yıldız Salman, «Posta ve Telgraf Nezareti Binası», DBİst.A, vol. 6, 279.

26 Kayserilioğlu and Kuntay, “Postahaneler”, p. 281.

27 Yazıcı, “Tanzimat Döneminde Osmanlı Haberleşme Kurumu”, pp. 177-178; Geçmişten Günümüze Posta, p. 158.

28 Yazıcı, “Tanzimat Döneminde Osmanlı Haberleşme Kurumu”, p. 151, 172-173.

29 Basiretçi Ali Efendi, İstanbul Mektupları, prepared by Nuri Sağlam, Istanbul: Kitabevi, 2001, pp. 440-441.

30 Yazıcı, “Tanzimat Döneminde Osmanlı Posta Örgütü”, p. 1642.

31 “Postacılar”, DBİst.A, vol. 6, pp. 279-280.

32 Stanford J. Shaw and Ezel Kural Shaw, Osmanlı İmparatorluğu ve Modern Türkiye, translated by Mehmet Harmancı, Istanbul: E Yayınları, 2000, p. 282.

33 Geçmişten Günümüze Posta, pp. 166-167.

34 Basiretçi, İstanbul Mektupları, pp. 339-341, 348-354.

35 Basiretçi, İstanbul Mektupları, pp. 627-628.

36 Salih M. Kuyaş, “Posta Tarihi ve Kapitülasyon Postahaneleri-I”, TT, 1984, vol. 1, p. 51.

37 Geçmişten Günümüze Posta, pp. 175-176.

38 M. Bülent Varlık, “Bir Yarı-Sömürge Olma Simgesi: Yabancı Posta Örgütleri”, TCTA, vol. 6, 1653.

39 Kayserilioğlu and Kuntay, “Postahaneler”, p. 280; Yazıcı, “Tanzimat Döneminde Osmanlı Posta Örgütü”, pp. 1646-1647.

40 Feroz Ahmad, İttihat ve Terakki 1908-1914, tr. Nuran Yavuz, Istanbul: Kaynak Yayınları, 2004, p. 87.

41 Geçmişten Günümüze Posta, p. 180.

42 Varlık, “Bir Yarı-Sömürge Olma Simgesi”, pp. 1655-1656.

43 Mustafa Kaçar, “Osmanlı Telgraf İşletmesi”, Çağını Yakalayan Osmanlı, ed. Ekmeleddin İhsanoğluand Mustafa Kaçar, Istanbul: İslam Tarih, Sanat ve Kültür Araştırma Merkezi, 1995, p. 46.

44 Kaçar, “Osmanlı Telgraf İşletmesi”, p. 47; BOA, İrade-Dâhiliye, no. 1053/7919 (10 August, 1847 - 27 Şaban 1263)

45 Geçmişten Günümüze Posta, pp. 188, 190.

46 Neriman Ersoy Hacısalihoğlu, “Kırım Savaşında Haberleşme: Varna Telgraf Hattı Şebekesi”, Savaştan Barışa: 150. Yıldönümünde Kırım Savaşı ve Paris Antlaşması (1853-1856) Bildiriler, Istanbul: İstanbul Üniversitesi Edebiyat Fakültesi Tarih Araştırma Merkezi, 2007, p. 122.

47 Lutfi Efendi, Târih, prepared by Münir Aktepe, Istanbul: İstanbul Üniversitesi Edebiyat Fakültesi, 1984, vol. 9, pp. 118-119; BOA, İrade-Dâhiliye, no. 326/21244 (22 August, 1855 - 8 Zilhicce 1271).

48 BOA, İrade-Dâhiliye, 326/21244; Kaçar, “Osmanlı Telgraf İşletmesi”, p. 60.

49 Kaçar, op.cit, p. 83.

50 Hacısalihoğlu, “Kırım Savaşında Haberleşme”, p. 129.

51 BOA, İrade-Hariciye, no. 140/7343 (20 February, 1857 - 25 Cemâziyelâhir 1273).

52 Hacısalihoğlu, op.cit, pp. 129-130; Kaçar, “Osmanlı Telgraf İşletmesi”, p. 81.

53 Kaçar, op.cit, p. 46.

54 Semavi Eyice, “İstanbul’da İlk Telgrafhane-i Amire’nin Projesi (1855)”, TD, 1984, vol. 34, pp. 61-68.

55 Yazıcı, “Tanzimat Döneminde Osmanlı Haberleşme Kurumu”, pp. 190-192.

56 Kaçar, “Osmanlı Telgraf İşletmesi”, pp. 107-108.

57 Orhan Koloğlu, “Yeni Haberleşme ve Ulaşım Tekniklerinin Osmanlı Toplumunu Etkileyişi”, Çağını Yakalayan Osmanlı, ed. Ekmeleddin İhsanoğlu and Mustafa Kaçar, Istanbul: İslam Tarih, Sanat ve Kültür Araştırma Merkezi, 1995, p. 604.

58 Kaçar, “Osmanlı Telgraf İşletmesi”, pp. 108-109.

59 Yazıcı, “Tanzimat Döneminde Osmanlı Posta Örgütü”, pp. 1649-1650.

60 Yazıcı, “Osmanlı Telgraf Fabrikası”, TDA, 1983, vol. 22, pp. 76-80.

61 Yazıcı, “Tanzimat Döneminde Osmanlı Haberleşme Kurumu”, p. 205. For the Ottoman telegraph and language subject, Nesimi Yazıcı, “Osmanlı Telgrafında Dil Konusu”, AÜİFD, 1983, vol 26, pp. 751-764.

62 Kaçar, “Osmanlı Telgraf İşletmesi”, pp. 117-118; Geçmişten Günümüze Posta, p. 196.

63 Basiretçi, İstanbul Mektupları, p. 659.

64 Kaçar, “Osmanlı Telgraf İşletmesi”, pp. 52, 78.

65 Koloğlu, “Yeni Haberleşme”, p. 605.

66 Stanford-Ezel Kural Shaw, Osmanlı İmparatorluğu ve Modern Türkiye, vol. 2, p. 281.

67 Niyazi Berkes, Türkiye’de Çağdaşlaşma, prepared by Ahmet Kuyaş, Istanbul: Yapı Kredi Kültür Sanat Yayıncılık, 2003, p. 344.

68 Cemal Kutay, Şehit Sadrıazam Talat Paşa’nın Gurbet Hatıraları, Istanbul: Kültür Matbaası, 1983, vol. 1, p. 204.

69 Bülent Çukurova, Kurtuluş Savaşı’nda Haberalma ve Yer altı Çalışmaları, Ankara: Ardıç Yayınları, 1994, pp. 29, 60.

70 S. Amann, “Telegraphy and Telephony”, A Dictionary of Nineteenth-Century History, ed. J. Belchem and R. Price, London: Penguin Group, 2001, p. 605.

71 Orhan Koloğlu, Abdülhamit Gerçeği, Istanbul: Pozitif Yayınları, 2007, p. 275.

72 Aliye Önay, “Türkiye’de Telefon Teşkilatının Kuruluşu”, Çağını Yakalayan Osmanlı, ed. Ekmeleddin İhsanoğlu and Mustafa Kaçar, Istanbul: İslam Tarih, Sanat ve Kültür Araştırma Merkezi, 1995, pp. 123-125.

73 Önay, op. cit, pp. 127-133.

74 Turgut Tan, “Osmanlı İmparatorluğunda Yabancılara Verilmiş Kamu Hizmeti İmtiyazları”, SBFD, vol. 22, no. 2, (1967) pp. 300-301.

75 Ayşe Hür, “Telefon”, DBİst.A, vol.6, 242.

76 Önay, “Türkiye’de Telefon Teşkilatının Kuruluşu”, p. 133.

77 Önay, op. cit, p. 134.

78 Orhan Koloğlu, “Basın”, DBİst.A, vol. 2, p. 69.

79 Koloğlu, op.cit., p. 71.