No other city in the world has ever been depicted or photographed like Istanbul, for no other city has the topographical features that can provide such a deep and wide perspective.

The oldest extant document drawn of this city is probably the view of Constantinople in Tabula Peutingeriana, drawn by the German-born Konrad Perting (1465-1547), based on the world map prepared by Vipsanio Agrippa (b. 64 BC/ d. 12 BC).

Another drawing from the early period is a view of Istanbul that appeared in the Latin travel book Liber Insularum Archipelagi, by Cristoforo Buondelmonti of Italian origin (1385-1430); there are also views that were produced from this work at later dates.1 The Istanbul view drawn by Giovanni Andrea Vavassore in the early sixteenth century provides us with information about what the city looked like at the end of the fifteenth century. Istanbul’s first panorama was drawn by the Danish painter Melchior Lorichs in 1559. He became a member of Augier Ghislain de Busbecq’s (Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq) delegation, arriving in the city on January 22, 1555 and returning to Vienna in the second half of 1559. Creating many drawings during his time in Istanbul, the most seminal work of the artist is a 45x11.275 cm2 black, white and sepia work. This drawing, made from the Galata Tower, includes a view that stretches from Sarayburnu to Eyüp. At the same time, other important visual documents are the view of Istanbul drawn by Matrakçı Nasuh at the starting point of Süleyman the Magnificent’s military expedition to Iraq in 1534-1535 and Nakkaş Osman’s view of Istanbul.

Of the many landscapes and structural drawings by numerous artists in almost every century, a ten-piece panorama drawn by Philipp Ferdinand von Gudenus3 in 1740 from the garden of the Swedish Embassy and the panorama from the early eighteenth century drawn by Cornelius de Bruyn,4 as well as the Istanbul view from the Harem by Antoine Ignace Melling5 have reached us today. Although drawn after photography became widespread, Joseph Schranz’s Bosphorus panoramas, dated 1855, should also be remembered.

Towards the end of the eighteenth century, in 1797, Robert Baker patented a technique of making 360-degree panoramic pictures. The first works produced with this technique were London panoramas. Following these works that were widely popular with the public, in 1801 a spectacular Istanbul panorama was exhibited. This panorama, prepared by Henry Aston Baker, the son of Robert Baker, was reproduced in 1813 in limited numbers with the “aqua-tinta” technique, colored by hand, and consisted of a total of eight pieces sized 65x40 cm.6 After this date, many pictures and panoramas were drawn by artists, such as Eugène Flandin (d.1889), Montagu B. Dunn (d. nineteenth century), Joseph Schranz (d. 1867) by which time the era of the photograph had already started.

The first photograph known was achieved by the retired French military officer Joseph Nicéphore Niépce in 1826 after an eight-hour exposure time; it was a blurry photograph of pigeon nest on the roof of a hut.7 Niépce started to work on developing this technique in 1829 by consociating with Louis Jasques Mande Daguerre, who was engaged in similar work. In 1833, following the death of Niépce, Daguerre continue to work on these and managed to obtain an image with an exposure time of under thirty minutes.8 The French Science Academy officially gave this invention the name “daguerreotype” in August of 1839. In this regard, the oldest Ottoman document we can find is the news in Takvim-i Vekayi, dated October 28, 1839 (19 Sha’ban 1255). The historical evolution of the invention of photography, its technical features and its inventor Daguerre, as well as Englishman William Henry Fox Talbot, who was also carrying out research on this matter, were all mentioned in the news.9 As far as can be ascertained, the possibility of color photography was mentioned, something that had not been expressed elsewhere at this time.10

This technique, which found a place for itself in a local newspaper three months after being announced, spread rapidly. The first photographers started taking photographs with their equipment in places they found interesting. The geography of the Ottoman Empire, and particularly that of Istanbul, were among the first places where these pictures were taken.

In the 95th issue of Ceride-i Havadis, dated July 17, 1842, news was published that a travel photographer named Compas, one of Louis Daguerre’s students, took a photograph of Istanbul. Unfortunately, there is no information regarding where Compas stayed and his works. The first active photography artist who settled in Istanbul and took photographs with the daguerreotype method was the German Abresche, who had a studio near Perşembepazarı. The only extant daguerreotype by Abresche is the portrait of the Armenian goldsmith Nigogos Hovyan taken on March 21, 1843.11

In Istanbul, one of the most important daguerreotype studios that was professionally active was the one belonging to the Italian Carlo and Giovanni Naya brothers. There are three extant portraits attributed to the Naya brothers, two of these belonged to Osman Hamdi Bey (d. 1910), and one belonged to his father, Ibrahim Edhem Pasha (d. 1893). Another studio that worked with this technique belonged to the Frenchman Laurent Astras, who advertised in the Ceride-i Havadis dated January 27, 1847.

With a fall in the prices of daguerreotypes in the early 1850s, studios gradually increased in number and amateurs who were interested in this technique, made photography a part of Istanbul’s daily life. For example, it is known that twice a year, Tabibart, a shop owner in Galata, placed an advertisement in the Journal de Constantinople, notifying the public that he was selling cameras and devices of “daguerreotype” and “calotype” techniques.

As can be seen from this announcement, not only the daguerreotype, but also the calotype technique was being used at this time. Obtaining positive printing from negative images in the laboratory environment, a traditional photography method, is still a method that is valid today. This was invented by the English scientist William Henry Fox. He received the patent for this method on February 8, 1841, and was known as the “talbotype.” However, in the field of international photography this word would later be replaced with the word “calotype.”

The word “photograph” means “the inscription of light” and is a combination of the Greek words “photos” and “graphos.” Being used for the method invented by Talbot, calotype means “beautiful imprint.” The sharp lines and deep contrasts of the daguerreotype photographs, placed on a shiny surface of silver coated metal, gave way to the softer transitions and lines, with colors ranging between white, grey and black.12

In the early 1850s, in Istanbul professional photographic studios started to open, one after the other, particularly in Beyoğlu. The first photographic studio was opened by Vasilaki Kargopulo. Then Ernest Edouard de Caranza, who worked with his partner Maggi between 1852 and 1854, and the German Rabach, who came to Istanbul between 1855 and 1856, opened a daguerreotype studio; later this was transferred to Vincent Abdullah in 1858. The Frenchman Alphonse Durand and another Frenchman, Jules Derain, were prominent photographers of this period.

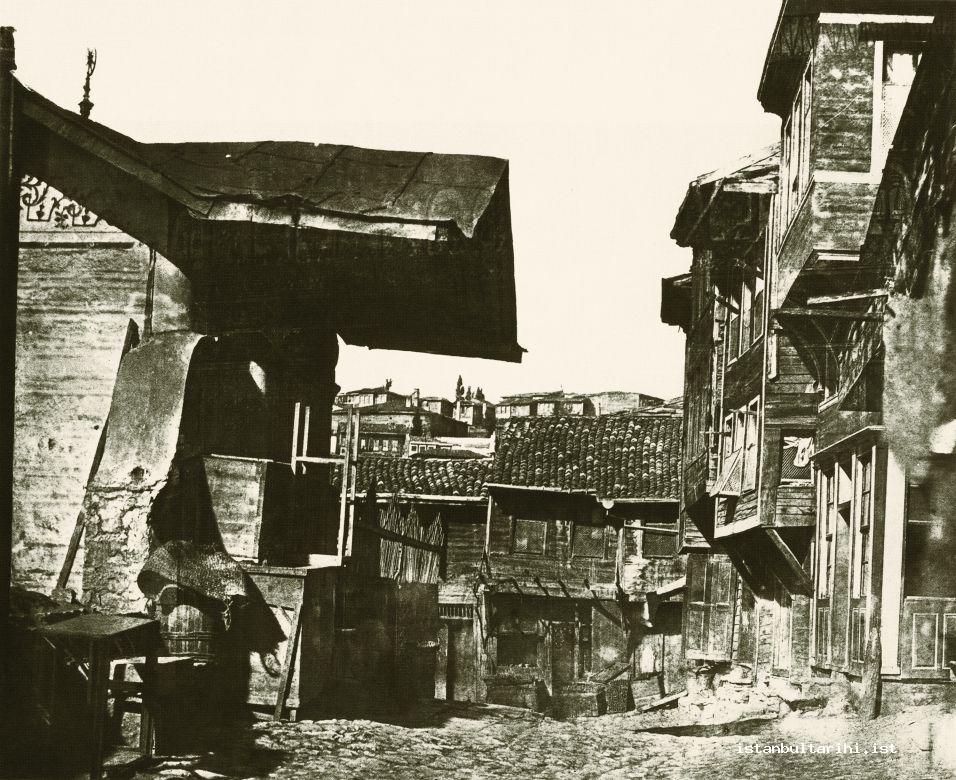

At this time, in addition to studio photographs, outdoor and landscape photographs, and photographs of architectural monuments were also taken. However, maybe because there was little demand, only a few images have survived to our period from the outdoor shoots, and thus they are rare as compared to portraits. The oldest known examples of outside daguerreotype pictures are the frames taken by the French travel photographer, Joseph Philibert Girault de Prangey. Most of these were taken in 1843; these photographs offer a panorama of Istanbul, including the Bebek Yorgaki Çelebi House, the Bebek Fishponds, the Ortaköy Coastal Mansion, the Üsküdar Ayazma Mosque, the Topkapı Palace Alay Pavilion and the Beyazıt Tower. Meanwhile, identifying himself as sürücü in his own handwriting, the portrait-sized 95x122 mm photograph is considered to be the oldest photograph with a costume and profession theme from Istanbul. The first photographer to use the calotype technique in Istanbul was the British George W. Bridges. Following Bridges’s photo shoots in 1846, Dr. Claidus Galen Wheelhouse took a series of photographs when he visited Istanbul; however, none of these frames have survived.

The oldest extant photographs of Istanbul taken with the calotype method belong to the Irish photographer, John Shaw Smith. Images of an avenue in Beyoğlu, Tophane Kılıç Ali Paşa Mosque, Sultanahmet Square and Ayasofya were shot by Smith, who visited Istanbul in November 1851; these photographs are significant records of the nineteenth century. The French architect Alfred-Nicholas Normand is another artist who took a range of Istanbul photographs using the same method between November 1851 and January 1852. In March 1852, the French Alphonse Durand took a series of photographs; a few of these survive today, such as the Galata Bridge, the pier from Beyazıt Tower, and Süleymaniye Mosque. These photographs were taken using both the daguerreotype and calotype methods. Afterwards, photographers like Dubois de Nehaut, Pierre Tremaux and Pietro Luchini took various pictures of Istanbul.

The first extant set of photographs of Istanbul consists of 75 frames taken by Claude-Marie Ferrier at the end of 1859. Using the daguerreotype method when first starting photography, Ferrier later developed the technique of making positive stereographic photographs on albumen glass plate; this method brought him fame.13 With a high documentary quality, two of these photographs14 showing the Topkapı Coastal Mansion, which burnt down in a fire on August 11, 1863, as well as interesting and dramatic photographs like the Hayratiye Bridge15 between Unkapanı and Azapkapı, Anadoluhisarı,16 and the Godefroy de Bouillon sycamore in Büyükdere.17

In the early 1850s, the number of both studio and traveler photographers were low; the reason for this was that almost all photographers had to use either the daguerreotype or calotype methods, both of which required advanced technical knowledge and manual skills. The Englishman Frederick Scott Archer paved the way of the photographers with the wet collodion method he discovered in March 1851. Sixteen fairly important photographs of Istanbul’s history were published by Francis Bedford using this method in May 1862. There are also images of Istanbul which were taken and exhibited in 1864 by Henri Bevan at almost the same date.

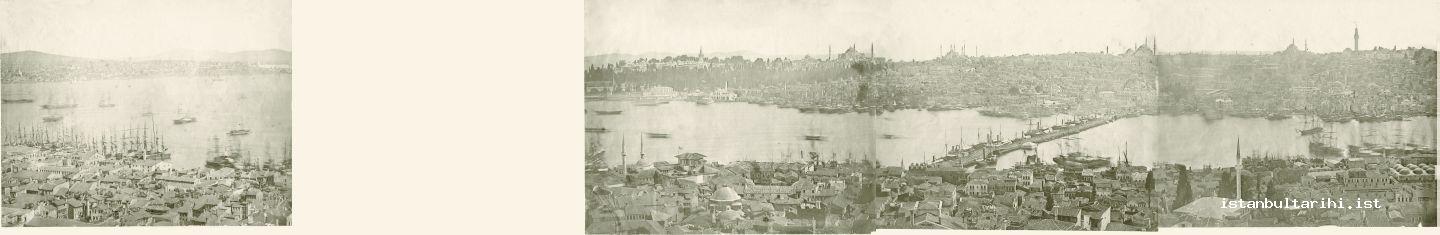

The most important name with regards to the history of Middle Eastern photography in the nineteenth century is Felix Bonfils. The French photographer ran a studio in Beirut which was in operation from 1867 to 1918. Visiting Istanbul in the early 1870s, Bonfils took series of photographs. Of these shots, a six-frame panorama shot of Istanbul from the Galata Tower survives today and is crucial for identifying the structures of the period.18

As a result of advances in optics, the camera developed by the Frenchman Adolphe Disderi was able to shoot photographs measuring 60x90 mm; this was significant in spreading photography. After some time, another method, known as stereograph, started to gain favour; this took up from both daguerreotype and calotype methods. The British Charles Wheatstone, who is also known for his contributions to the invention of the telegraph and the microphone, invented this technique. Twin frames were shot from two cameras, the centers of which were 90 mm apart from one another; they were viewed with a similar device which created a three-dimensional image, thus giving a feeling of perspective.

In 1863, the Frenchman Charles Gérard and in 1869 Jules Andrieu, took series of Istanbul photographs using the stereograph technique. Then, in 1871, Frank Mason Good, who came to Istanbul and worked using the collodion technique, conducted research using other techniques as well as the stereograph technique. These frames, the majority of which are still extant today, are regarded as the most important photographs of Istanbul from the third quarter of the nineteenth century.19

Undoubtedly, the most important name in the history of Istanbul photography is James Robertson. Robertson arrived in Istanbul in 1841 during the renovation efforts of the Ottoman mint and started to work as başhakkâk (head engraver) at the mint. It is not known how he started photography or from whom he received technical training. Robertson was a painter as well as a hakkâk; a watercolour that he painted, most likely in 1849, was used in the book A Month in Constantinople,20 published in 1850 by Albert Smith. It is also known that Istanbul-themed engravings which benefited from the first photographs by Robertson were published in the Illustrated London News between 1853 and 1855. Published in May and June of 1854, in this book, under four different engravings of the troops of the British Empire that were stationed close to the Üsküdar Selimiye Barracks we can read “From a daguerreotype by J. Robertson.”

One of Robertson’s earliest photographs is the engraving of Dolmabahçe Palace Gate under construction; this was also published in the Illustrated London News on September 8, 1853. Many Istanbul photographs made with the acidic-paper printing technique and signed by Robertson have survived. From spring of 1856, Robertson, who had also earned a reputation for the photographs he took during the Crimean War, started to work with his brother-in-law Felice Beato. Henceforth, during this partnership, which continued until 1867 when they went out of business due to increasing competition, they would sign the photographs they took “Robertson & Beato.”21

Another foreign photographer working in Istanbul during the early period was the French engineer Ernest Edouard de Caranza. Caranza is known to have started taking photographs in February-March of 1852. The Istanbul series he composed in 1852 was the earliest and most in-depth attempt at documentation regarding Istanbul. These frames, the majority of which were from 1852, were taken as waxed paper negatives using the calotype technique. The Fountain of Ahmet III, Galata Tower, Sultanahmet Square and Ayasofya, Dolmabahçe Palace, Küçüksu Fountain and various Beykoz images are among the important photographs in this collection. Caranza, who opened a studio in Beyoğlu with his partner Maggi in 1853, ended this enterprise in early 1855.22

The first domestic photographic studio belonged to Vasilaki Kargopulo, who started operating in 1850 on the Grand Rue de Pera 311, next to the Russian Embassy in Beyoğlu. First taking portraits in the studio, Kargopulo started to prepare a collection of photographs under the title “Costume and Professions”; he thought that these would attract the attention of tourists visiting Istanbul. In his early photographs, Sultanahmet Square and Topkapı Palace were depicted, as well as stereographs of Nuruosmaniye and Sultanahmet Mosques, taken in 1860.23 Having worked in close affiliation with the palace during the reign of Abdülmecid (1839-1861), Vasilaki Kargopulo lost this privilege when Sultan Abdülaziz (1861-1876) came to the throne. The enthronement of Sultan Abdulhamid II (1876-1909) was the reintroduction of success for Kargopulo, who had tried support himself through his own efforts for many years. Until his death in 1886, Kargopulo kept the title Mabeyn-i Hümayun Fotoğrafçısı (royal photographer); this title had been conferred upon him shortly after by the new sultan, who was keen on photography.

In addition to many Istanbul photographs taken at various times between 1865 and 1885, most of which have the dimensions 210x270 mm, seven panoramas consisting of 36 frames taken between 1878 and 1879 are very important for the history of Istanbul photography. Taken in 1875, one from the Galata Tower, another from Beyazıt Tower and two more Istanbul panoramas belong to Kargopulo. After the sudden death of Vasilaki Kargopulo on March 26, 1886, Konstantin Kargopulo was bestowed the title of “Royal Photographer” on April 11, 1886, in place of his father. Konstantin went out of business on May 27, 1895; after having difficult times he lost his title in early 1889, due to the lack of success he had in photography.

Another name that is important in the history of photography was Pascal Sebah. Sebah opened a studio at No 10 Tomtom Street, which was called El Chark Société Photographic; he was the second Ottoman citizen after Kargopulo to work professionally. In spite of Pascal Sebah’s high-quality works in landscape photography between 1862 and 1875, only a few have reached us from his first Istanbul collection, prepared in 1862. There are four hundred photographs and six panoramas in the company catalogue that Sebah published under the name “Catalogue des Vues d’Egytpe, Nubie, Athenes, Constantinople et Brousse” in 1875. There are two Istanbul panoramas, one taken from Galata Tower, the other from Beyazıt Tower; each consists of ten frames. In addition, there are several landscape and architectural photographs of Istanbul, numbered between 1 and 141 in this catalogue. The Great Fire of Beyoğlu in 1870, as well as the fire in Tomtom Street Studio in 1881, created financial and emotional difficulties for the artist. While he was trying to recover from these setbacks, Sebah passed away on June 25, 1886. The studio urgently needed to find another partner in order to continue. Thanks to the efforts of his mother, the fourteen-year old Jean Pascal was able to make an agreement with the French photographer Polycarpe Joaillier in 1888; the studio’s name was changed to Sebah&Joaillier. This studio purchased the archives of the Abdullah Brothers in 1899. J. Sebah sold the studio in 1908 after Joaillier returned to Paris. The studio continued for nearly a century, until the last owner Bedros İskender settled down abroad in 1950.

Many surviving photographs of Istanbul that were taken during the period of Pascal Sebah and Sebah&Joaillier, provide substantial visual documentation of the history of Istanbul. Pascal Sebah was an expert in photography; he was so experienced in photography that even in these early days he was able to produce a montage of the Maiden’s Tower on a landscape photograph which he had taken in the early 1870s. The long and thin rowboat in the foreground of the frame, in which two rowers and three women are sitting, is a studio photograph that was later placed on the photograph, named “La Tour de Léandre.”24 There are 1,660 frames in the catalogue, which includes over 2,000 photographs taken by Sebah&Joaillier after 1887; these document various Istanbul landscapes, Ottoman costumes, professions, and street vendors.

The most important photographic studio in the Ottoman Empire undoubtedly was the studio which was opened by Viçen Abdullah (Abdullahyan) in Beyoğlu in 1858; this studio was known as “Abdullah Fréres.” Viçen Abdullah, who was the first imperial photographer, started his adventure in photography with the German artist Rabach, who came to Istanbul in 1856. After Rabach’s decision to return to Germany in 1858, Viçen took over the studio. He had four brothers named Gomidas, Hovsep, Kosmi and Kevork, and three sisters. Taking portrait shoots on daguerreotype and paper initially, this studio operated until 1899, after which it was sold to Sebah&Joaillier. At first, his brothers Hovsep and Kevork help Viçen. During this period, the studio was known as “Vincent Abdullah Frères”; later it became known as “Abdullah Frères” in 1861. The year 1863 was a fresh start for the Abdullah brothers, and their being given the title of “Ottoman Empire Photographer” enabled them to improve rapidly.

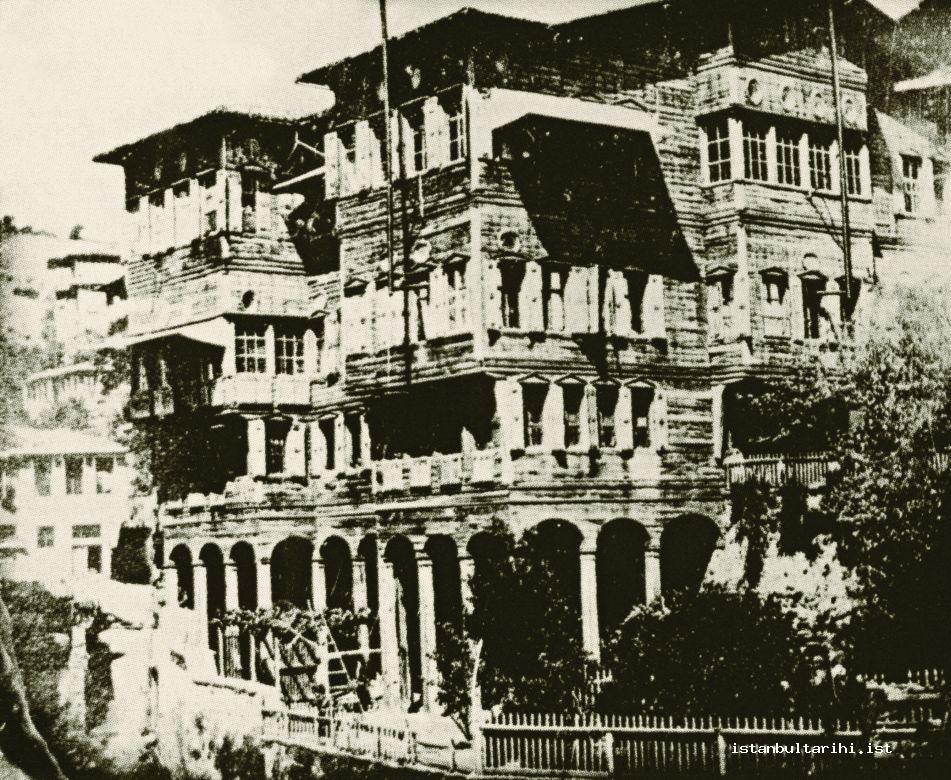

The first exhibition featuring their work was at the Sergi-i Umumi-i Osmani, which was held in Sultanahmet Square in February 1863. Among the outdoor scenes, the most successful of which had been taken between 1862 and 1866, the images of Beyazıt and Sultanahmet, Beykoz streets and Kurbağalıdere Mansions from post-1865 are images of extraordinary beauty.

The Paris Exhibition of 1867 brought great success for the Abdullah Brothers. In particular, their interest in landscape photographs paved the way for their being renowned all over Europe. At the beginning of the 1870s, Kosmi Abdullah started a studio in Beyazık Kökçübaşı; this is striking, demonstrating that photographic studios also started to operate inside the city walls. After a short time, Mateos Papazyan became a partner in this studio. In 1879 Kosmi transferred this studio to Nikolaos Andriomenos.

Starting another studio in Tarlabaşı, Kosmi Abdullah continued there until the end of the 1880s. Kosmi Abdullah’s sons, Abro and Levon Abdullah, opened the “Abdullah Frères Fils” studio. The dethronement of Sultan Abdülaziz on May 29, 1876 was the most harrowing event which the Abdullah brothers experienced. However, they were still able to take advantage of their close affiliation with the palace. Their close links with the Russian Army, which had advanced as far as Yeşilköy in the aftermath of the Ottoman-Russian War of 1877-1888, however, were the subject of Abdulhamid II’s disapproval, and the title of imperial photographer was taken from them. The sudden death of Vasilaki Kargopulo in 1886 and his son Konstantin’s unsuccessful attempts at photography meant that Viçen Abdullah was given the duty of imperial photographer once again, after a period of more than a decade. However, any attempt to revive the glorious days of the past was a dream. The studio, which was sold to the Sebah&Joaillier Company in 1899, produced photographs after that date under the name of “S&J Successors.”

Guillaume Berggren holds a special place in the history of Istanbul photography. Coming to Istanbul from Sweden in 1866, Berggren obtained his first experience in photography in Büyükdere, and then moved to Beyoğlu. First taking portraits, the artist then specialized in landscape photography.

It is thought that Berggren prepared the first extensive Istanbul collection in 1875. In addition to many landscape photographs, Berggren’s two eight-frame Bosphorus and Istanbul panoramas, with Galata and Beyazıt panoramas,25 taken in 1875 and 1876, present powerful images. The albums he prepared for the Kasımpaşa Tersane and the Cibali Tobacco Factory in 1887 are records of the period’s industrial structures. The artist, who endured economic hardships in the early 1910s, sold a series of glass negatives to the German Embassy and then passed away on August 26, 1920.

Taking over Kosmi Abdullah’s studio in Beyazıt in 1879, Nikolaos Andriomenos’s studio ranks among the most prominent in Istanbul. Then he moved his studio to Beyoğlu, where he had generally taken portraits. Although he started to take outdoor photographs from 1895, and the number of negatives in the Istanbul collections exceeded 260, most of these frames were not of high quality. After Nikolaos Andriomenos passed away in 1929, his son Athanasios engaged in portraits, using the name “Foto Saray”; the studio was closed down in 1955.

Three brothers, Yervant, Kirkor and Artin, opened a photographic studio named “Gülmez Kardeşler” in Beyoğlu in the early 1880s. In addition to portrait works, in the second half of 1880s they took a series of Istanbul photographs. In particular, the Istanbul panoramas they took between 1885 and 1900 were quite successful. They participated in the Chicago Exhibition in 1893; their success attracted the attention of Sultan Abdulhamid II. Subsequently, they were granted permission to use the title “Photographer of the Sultan.” In the early 1900s, the Gülmez Brothers transferred their studio to Aşil Samancı, where their activities in photography came to an end. After this period, changing its name to the “Apollon Photograph House” the studio continued to operate until 1922.

Boğos Tarkulyan, the oldest records concerning whom date back to 1882, was a distinguished photographer not only during the Ottoman Empire, but also during the early years of the Republic. His portraits of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk were used on the banknotes that were put into circulation on December 5, 1927. Tarkulyan started to work as an apprentice in the studio of the Karakasyan Brothers and then worked with the Abdullah Brothers. First working in Pangaltı, Tarkulyan moved to Beyoğlu in 1886, changing the name of his studio to “Phébus.” Having an inclination for landscape photography, after 1890, Tarkulyan undertook to record the Kağıthane and Bosphorus coasts in addition to his studio photographs. These 210x270 frames bear the name Phébus. In 51 photograph albums that were sent to the United States Library of Congress as a present from Sultan Abdulhamid II in 1893, two albums of 70 frames by Tarkulyan were included. Phébus Photograph House, which was damaged by fire in May 1900, went into service again after this date. Boğos Tarkulyan took a vast number of Istanbul photographs; he passed away in 1936. Tarkulyan also took the portraits of important political figures of the period, including the Shah of Iran Muzafferuddin, the German Emperor Wilhelm II, the Bulgarian Emperor Ferdinand I, and the Austrian Emperor Charles I.

In addition to the aforementioned studios, there were many other important studios in Istanbul after the 1850s. Among these studios, most of which carried out portraits and studio photography, there were other photographers who can be remembered as important photographers of the period. Paul Vuccino, who was known for photographing the Haydarpaşa-İzmit railway, the construction of which began in 1865; Constantin Fettel, who took a panorama view from Galata Tower, and who worked between 1888 and 1892; Tancréde Dumas, who created several stereographic images and took a panorama shot from the Galata Tower; Mihran İranyan, who took landscape photographs in addition to portraits; and the Karakaşyan Brothers, who took Istanbul panoramas from various angles, and a number of other landscape photographs.26 The 1870 fire destroyed all these photographic studios; this fire started in a house on Valide Çeşme Street and spread throughout the Tarlabaşı direction, destroying half of Pera.

The first Muslim artists who dealt with photography were all members of the military. Dating from the reign of Sultan Abdülaziz, the photographic art classes which were given in the military schools soon led to the training of photographers, such as Lieutenant Hüsnü Bey (b. 1844/d. 1896); Servili Ahmed Emin Bey (b. 1845/d. 1892); Üsküdarlı Ali Sami Bey (b. 1867/d. 1937); Bahriyeli Ali Sami Bey; Miralay Ali Rızâ Bey (b. 1850/d. 1907); and the artist Hüseyin Zekai Pasha (b. 1860/d. 1919).27 Unfortunately, we have no information regarding the pictures taken by Hüsnü Bey, who published Risale-i Fotoğrafya in 1871. Thus, Servili Ahmed Emin Bey should be regarded as the first military photographer in the Ottoman state. Meanwhile, many photographs taken by Üsküdarli Ali Sami Bey (Aközer), who was also the son-in-law of Ahmed Emin Bey, have survived to this day. Ali Sami Bey, who also created many Istanbul panoramas, made stereographs of his own house and home life, thus creating interesting documents apart from his military-related photographs.28

In order to avoid confusion with Üsküdarli Ali Sami Bey, Ali Sami Bey was referred to as “Bahriyeli.” As well as taking many pictures of Istanbul, Ali Sami Bey also took many photographs of the German Emperor Wilhelm II from his visit to Istanbul and the Hejaz.

Ali Enis Oza is the first to be remembered among the Istanbul photographers of the twentieth century. Unfortunately, we do not have much information about Oza, who was an amateur photographer. Before passing away in 1948, he took many photographs of Istanbul in the early years of the Republic.29 The Austrian Othmar Pferschy (1898-1984), who visited our country in 1926, is another photographer who left his mark on the early years of the Republic. He left behind 16,000 frame negatives for the magazine La Turquie Kemaliste, which began in 1935; these are indispensable visual documents for this period in Turkey and Istanbul.30 Hilmi Şahenk (1903-1972), who started off working as a photojournalist for Milliyet newspaper in 1925, was an artist who was in love with Istanbul.31 Other photographers who were working during this period were Selahattin Giz, Sami Güner, Müeddep Erkmen, Faik Şenol and Ara Güler; the latter is known as the doyen of photography in our country. I am of the opinion that the evaluation of photography artists who created views of Istanbul in the post-1950 era, most of whom are still alive, should be done in later years.

Recently, a number of photographic albums of Istanbul have been published. Istanbul photographic albums by Aşil Samancı and Eugene Dalleggio,32 working as “T. Wild,”33 and dated 1900, are just some albums that can be mentioned.

The American photographer Lewis Wickes Hine (1874-1940) emphasized the importance of photography in reflecting reality when he stated “Although photographs do not lie, liars can photograph.”34 The invention of photography is a giant step in regards to the history of humanity. Contrary to visual documents based on personal perception, such as engravings or pictures, an objective documentation technique had now been developed. For example, we see that the claims “Istanbul was covered with trees, a green city,” which has been brought forward frequently, are unfounded and that from photographs, contemporary Istanbul is greener than it had been in the past. For this reason, photographs by the following the photographers should be mentioned.

The first frames known to belong to Istanbul are the 82x95 mm Topkapı Palace Procession Mansion (Fig 1) and Üsküdar Selimiye Mosque photographs taken with the daguerreotype technique (Fig. 2); also an Istanbul Panorama, with dimensions of 95x240, taken from Beyazıt Tower by Girault de Prangey can be added to this list.35 Another daguerreotype photograph from the early period is that of Bebek Yorgaki Çelebi House, which has not survived to our days (Fig. 3). As an example of the early period calotype photo, a street view from Beyoğlu, taken by John Shaw Smith in November 1851 can be given (Fig. 4). “Istanbul Panorama” by James Robertson in 1854, taken from Galata Tower, and the panorama photographs by Girault de Prangey in 1843, and by Alphonse Durand in 1852, taken from Beyazıt Tower are important visual documents that have reached us today (Fig. 5).36 Spanning from Üsküdar to the Old Palace in Beyazıt in five frames, the second frame of this panorama, which includes Topkapı Palace, is lost today. As can be seen from this panorama, except for Topkapı Palace garden, it is almost impossible to see even a single tree among the dense housing. The comparison of this panorama by Robertson with the panorama drawn by Melchior Lorichs three hundred years earlier might be an interesting study.

Some photographs are interesting because they show the errors that have been made over time. For example, we see in two photographs dated 1862-1863 that the part of Dolmabahçe Palace which faces the square was arranged with flower beds covered with low plants and no trees. Later, probably in the early periods of Sultan Abdulaziz or Sultan Abdulhamid II’s reign, we see that this part had been rearranged and trees were planted, making the palace fairly invisible today (Figs 6,7).37 Another important photograph is the photograph of Dolmabahçe Palace’s Muayede Hall taken by James Robertson between 1853 and 1854. In this photograph, which depicts a scene often used for engravings, there is a small boat pier in front of the Muayede Hall. By looking at the engravings, it is possible to understand that this image, which was assumed to be imaginary, was real and that this pier was later removed (Fig. 8).38 The photograph taken sometime by Pascal Sebah between 1865 and 1879, known as the Cuma Selamlığı in Ortaköy Mosque, on the other hand, reveals a fact that had been shrouded in secrecy in written documents. In this photograph, two 26-oar sultanate boats are moored at the pier of the mosque, waiting for the sultan, probably to take him to Beylerbeyi Palace. It is still unknown why there were two sultanate boats; a similar scene is depicted in another photograph (Fig. 9).39 Two consecutive photographs by the Abdullah Brothers of the return journey of Sultan Abdülaziz from Europe on August 7, 1867, are still extant today; these are pictures that reflect the splendor of Istanbul (Fig. 10).40

We have been gravely mistaken about Istanbul’s visual history. Some of our misconceptions are rooted in society and this prevents us from coming to the correct conclusion. I wish that in addition to documents, we could make more space in our lives for the photos that have appeared before us during the recent 170-year history of this city. I strongly believe that it is worthwhile for those who will decide the future of this city in which we reside to scrutinize these visual documents thoroughly and take the lead by acknowledging the facts.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Koloğlu, Orhan, Basınımızda Resim ve Fotoğrafın Başlaması, Istanbul: Engin Yayınlar, 1992.

Özendes, Engin, Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’nda Fotoğrafçılık (1839-1919), Istanbul: Haşet Yayınevi,1987.

Özendes, Engin, Abdullah Frères Osmanlı Sarayının Fotoğrafçıları, Istanbul: Yapı Kredi Yayınları,, 1998.

Özendes, Engin, Sébah&Joaillier’den Foto Sebah’a Fotoğrafta Oryantalizm, Istanbul: Yapı Kredi Yayınları, 1999.

Öztuncay, Bahattin, “Fotoğraflarda İstanbul”, İstanbul Ansiklopedisi, Istanbul: NTV Yayınları, 2010, pp. 393-396.

FOOTNOTES

1 Semavi Eyice, Cristoforo Buondelmonti, Istanbul 1964.

2 Cyril Mango and Stéphane Yerasimos, Melchior Lorichs’ Panorama of Istanbul 1559, Bern: Ertuğ & Kocabıyık, 1999.

3 Boppa Augusta, XVIII. Yüzyıl Boğaziçi Ressamları, tr. Never-Celbiş Yucel, Istanbul: Pera Turizm ve Ticaret, 1998, pp. 159-160.

4 Corneille Le Brun, Voyage au Levant, Paris: Guillaume Cavelier, 1714, plan 22A.

5 Ekrem Işın (ed.), Uzun Öyküler: Melling ve Dunn’ın Panoramalarında İstanbul, Istanbul: Suna ve İnan Kıraç Vakfı İstanbul Araştırmaları Enstitüsü, 2008.

6 Sedad Hakkı Eldem, İstanbul Anıları, Istanbul: Aletaş Alarko Eğitim Tesisi, 1979, pp. 28-29, 48-51.

7 Alberto Modiano, Fotoğraf Tarihine Giriş, Istanbul: Art Studio Yayıncılık, 2007, pp. 21-23.

8 Modiano, Fotoğraf Tarihine Giriş, pp. 24-29.

9 Modiano, Fotoğraf Tarihine Giriş, pp. 32-35.

10 Hidayet Nuhoğlu and Orhan Çolak, “Türkiye’ye Fotoğrafın Girişi”, Gezgin, no. 6 (2007), pp. 6-13.

11 Kevork Pamukciyan, “Osmanlı Döneminde Fotoğrafçılık”, TT, vol. 48 (1987), p. 28.

12 Bahattin Öztuncay, Dersaadet’in Fotoğrafçıları, Istanbul: Aygaz, 2003, p. 29.

13 Öztuncay, Dersaadet’in Fotoğrafçıları, p. 87; Sophie Basch (ed.), Voyage a Constantinople 1860: Léopold de Belgique Photographie de Claude-Marie Ferrier, Bruxelles: Editions Complexe, 1997.

14 Basch (ed.), Voyage, p. 131, 149; M. Sinan Genim, Konstantiniyye’den İstanbul’a: XIX. Yüzyıl Ortalarından XX. Yüzyıla Boğaziçi’nin Rumeli Yakası Fotoğrafları, İstanbul, Istanbul: Suna ve İnan Kıraç Vakfı İstanbul Araştırmaları Enstitüsü, 2006, pp. 158-161.

15 Basch (ed.), Voyage, p. 146.

16 Basch (ed.), Voyage, p. 99.

17 Basch (ed.), Voyage, p. 140.

18 Öztuncay, Dersaadet’in Fotoğrafçıları, p. 91.

19 Öztuncay, Dersaadet’in Fotoğrafçıları, pp. 92-97; Genim, Konstantiniyye’den İstanbul’a (2006), pp. 150-151.

20 Öztuncay, Dersaadet’in Fotoğrafçıları, p. 109

21 Bahattin Öztuncay, James Robertson Pioneer of Photography in the Ottoman Empire, Istanbul: Eren Yayıncılık, 1992; Öztuncay, Dersaadet’in Fotoğrafçıları, pp. 101-153; Genim, Konstantiniyye’den İstanbul’a (2012), pp. 528-529.

22 Öztuncay, Dersaadet’in Fotoğrafçıları, pp. 154-175; Genim, Konstantiniyye’den İstanbul’a (2012), pp. 122-123, 140-141.

23 B. Öztuncay, Vasilaki Kargopulo, Istanbul: Birleşik Oksijen Sanayi, 2000, pp. 33-37.

24 Genim, Konstantiniyye’den İstanbul’a (2006), pp. 98-99.

25 Genim, Konstantiniyye’den İstanbul’a (2006), pp. 302-303; Genim, Konstantiniyye’den İstanbul’a (2012), pp. 836-837.

26 Öztuncay, Dersaadet’in Fotoğrafçıları, pp. 302-334.

27 Öztuncay, Dersaadet’in Fotoğrafçıları, pp. 335-343.

28 Engin Çizgen, Photographer/Fotoğrafçı Ali Sami (1866-1936), Istanbul: Haşet Kitabevi,1989.

29 Genim, Konstantiniyye’den İstanbul’a (2012), pp. 464-465, 500-501

30 Gülderen Bölük, İstanbul’un 100 Fotoğrafçısı, Istanbul: İstanbul Büyükşehir Belediyesi Kültür A.Ş., 2009, pp. 76-77.

31 Hilmi Şahenk, Bir Zamanlar İstanbul, Istanbul: İstanbul Büyükşehir Belediyesi, 1996.

32 Costas M. Stamatopoulos, Constantinople, Turin: Umberto Allemandi & C, 2009.

33 Jean-François Pérouse, Constantinople 1900 Journal Photographique de T. Wild, Paris: Kallimages, 2010.

34 Peter Burke, Afişten Heykele Minyatürden Fotoğrafa Tarihin Görgü Tanıkları, tr. Zeynep Yelçe, Istanbul: Kitap Yayınevi, 2003, p. 21.

35 Öztuncay, Dersaadet’in Fotoğrafçıları, pp. 69-74.

36 Genim, Konstantiniyye’den İstanbul’a (2006), pp. 16-17.

37 Genim, Konstantiniyye’den İstanbul’a (2006), pp. 158-161, 186-189.

38 Genim, Konstantiniyye’den İstanbul’a (2006), pp. 208-209.

39 Genim, Konstantiniyye’den İstanbul’a (2006), pp. 286-287.

40 Genim, Konstantiniyye’den İstanbul’a (2006), pp. 24-27.