Throughout the world, the film industry is centered around a large city known for its cultural, political and economic influence, and one that has an ease of transport. For example, the center of mainstream American cinema is the Hollywood neighborhood of Los Angeles, California. Similarly, the center for British cinema is London, Paris for French cinema, Rome for Italian and Mumbai for Indian cinema. Since not only was Istanbul the most important political, economic and cultural center of the region for centuries, but also offered great communication and transportation opportunities with Europe and the world, Turkish cinema was centered around the city of Istanbul. More specifically, Turkish cinema was established in the Beyoğlu district, an important cultural center of the city.1 In the era of Turkish cinema, from the 1950s to the end of the 1980s, Yeşilçam lane in the Beyoğlu district reflected this, as it was a location where many film-makers settled. In addition its features as a city of history and tourism, Istanbul became a fertile source for cinema, both historically and sociologically, due to the multicultural structure that derived from the great variety of religious and ethnic elements that resided in the city over the centuries; more particularly, the city offered inspiration due to the problems of urbanization that were the result of internal migration in the last five or six decades.

History of Istanbul Cinema

Following the world’s first screening by the Lumière brothers Auguste (b. 1862-d. 1954) and Louis (b.1864-d. 1948) in Paris in 1895, the charm of moving pictures projected on a white screen aroused great interest in the cinema from both individuals and governments. The images that attracted the most attention were those depicting different societies and geographies; this small number of black and white silent films lasted only a few minutes in length. Among these interesting films, there were images that belonged to the society and geography of the Ottoman State, which was one of the greatest Oriental states of the period. Indeed, the pioneers of cinema, the Lumiére brothers, also sent film makers to the Ottoman lands. The first person to shoot a film in Ottoman territory was a French citizen of Italian origin, Alexandre Promio (b. 1868 - d. 1926). In 1896, Promio recorded images of Turkish soldiers in Istanbul and İzmir. He also shot a series of scenes of the Bosphorus and Golden Horn districts of Istanbul. Promio was followed by Fèlix Mesguich (b. 1871-d. 1949), Francis Doublier (b. 1878-d. 1948), Charles Moisson (b. 1863-d. 1943) and Maurice Perrigot. They all worked for the Lumiére brothers and came to the Ottoman State between 1896 and 1899 to make films.2 Cinematic devices imported from Western countries in this period first appeared in major cities like Istanbul and İzmir. Foreigners and non-Muslim citizens in the Ottoman State became importers and operators for these cinematic devices. For example, Monsieur Constinsouza, a Frenchman, was a filmmaker who credited himself as being the first person to bring films to the Ottoman lands.3

The Ottoman State became aware of “cinematography” via a letter dated June 17, 1896; this was sent by Monsieur Jamin, a French citizen, to the Sublime Porte via the French Embassy. The date was only a year after the Lumiére Brothers’ first screening.4 In September, 1896, official institutions of the Ottoman State presented a positive report on cinematography. In this report, the description of cinematography as “an important medium for humanity in spreading science” became influential in starting cinematic activities in the Ottoman State and in its gaining recognition by the Ottoman Palace.5 The first screening of a motion picture in the Ottoman State was held at Yıldız Palace in the presence of Abdülhamid II (1876-1909). A French juggler named Bertrand held the screening for the sultan and courtiers, setting up a screen in the great chamber of Yıldız Palace.6 This first screening in the palace in 1897 was followed by the first public screening at Sponeck Pub, a workplace in the European Passage, on Hammalbaşı Avenue in Beyoğlu,7 organized by D. Hanri.8 The projector was operated with petroleum lamps since there was no electricity in Istanbul at the time. Although the pungent gas smell emanating from the lamps disturbed the captivated audience, they watched this first screening of the cinema, which they regarded as a “magical invention”, with great interest.9

There were no special venues in 1899 for screening films in Istanbul. Screenings generally took place in venues like theaters, circuses, coffee houses and pubs. In addition to D. Hanri, the names of Cambon and Monsieur Constinsouza stand out, as well as Sigmund Weinberg, an Istanbul-based Polish Jew born in Romania (1868 - 1954). After his first show at Sponeck, D. Hanri organized screenings at Fevziye Coffeehouse as well. Cambon organized film screenings at Varyete Theater and Monsieur Constinsouza held screenings at the theater in Halep Bazaar.10 The films that were screened were short documentaries and comedies.11

Sigmund Weinberg, unlike the others, owned a business selling cameras and apparatuses at number 28 Yüksekkaldırım (Galata). This business, which he started in 1889, enabled him to establish relationships with important circles. Weinberg also became the agent in the Ottoman State for camera and apparatus manufacturers in European companies, primarily the Lumiére Brothers. In cinematography, he was the Istanbul representative of Pathé Fréres Company, which bought all the cinematography rights from the Lumiéres in 1900. In response to rivalry among those who organized screenings in Istanbul, Weinberg tried to establish communication with the Ottoman Palace, resorting to different methods to tip the scales in his favor.12 In a petition that he wrote to Abdulhamid II in October 1899, Weinberg mentioned that filming the Ottoman army by foreigners would not be a good idea; rather he offered to do this for free and in the most fitting way for the sultan’s army. According to his petition, maneuvers and military parades of the Ottoman army would be filmed for free; however, these films would be shown to the public for a fee.13

At first, the cinema presented to the public a year after the first screenings by the Lumiére brothers “was regarded as sinful by certain circles for various reasons”;14 however, this attitude soon changed. The novelty and attraction of the cinema quickly overcame this negative attitude and the cinema found the chance to spread throughout the Ottoman State.15 It should be noted that Muslim Ottoman society, which still deprecated the theater, did not show any critical reaction towards the cinema.16 Indeed, the nightly screenings organized by D. Hanri during Ramadan in 1897 at the Fevziye Coffee House were watched with great interest by the people of Istanbul. The technical similarity between traditional Karagöz plays and the cinema is still the best explanation for this mild attitude towards the cinema among Istanbul residents.17 The most popular form of theater in those years in the Ottoman State, Karagöz prepared people for the concept of the cinema; the public entering a dark room for the cinema did not feel that there was anything wrong with this invention.18 Having been publicized in the first years in Istanbul with showings held in pubs, coffee houses and mansions, the cinema started to establish a presence in daily life. After a short time, the cinema became an accompaniment to Karagöz and traditional storytellers (Meddah), which were traditional Turkish performance arts held at night during Ramadan.19

On May 29, 1903, the Ottoman government issued the first regulation concerning cinematic activities. According to this regulation, the right to carry out cinema screenings in the Ottoman State was granted to everyone on a non-discriminatory basis for 35 years.20 Five years after this legal arrangement, the first censor in cinema activities was implemented with the decision made by the government on June 20, 1908. The decision reads as follows:

As we were informed that two Frenchmen attempted to rent No. 18 ferry of Şirket-i Hayriye and pull it with tugboats to the Bosphorus coastal piers, the Princes’ Islands, Bakırköy and the Gulf of İzmit, while having a cinematograph machine in it, supposedly in order to show cinematographic pictures to the public. Due to the unsuitable nature of such an undertaking, it is the sultan’s sublime decree that this should not be permitted.21

In the early Second Meşrutiyet period, which began with the reintroduction of the Kanun-i Esasi (constitution) on July 24, 1908, a strong opposition against the Party of Union and Progress in conservative circles started to emerge. In Ramadan 1908—October according to the Gregorian calendar—strong protests were held in which demands, such as the closure of pubs and theaters, the banning of cameras and restrictions on the freedom of movement for women were made.22 The ban on a film for reasons of “obscenity” again came into force in October 1908. Some films in screenings organized by a cinematography company in the Odeon film theater on Cadde-i Kebir (İstiklal Avenue) included obscenity. Because some films or some scenes in these films were not regarded as appropriate for public morals, they led to complaints being made about the aforementioned films. The Beyoğlu Administration banned the screenings in response to these complaints.23

Despite some negative reactions, cinema quickly became popular from when it was first introduced into the Ottoman State until the Second Meşrutiyet; it was an art form that was greatly appreciated by the public. Public interest created the need for permanent film theaters.24 Although the first film screening was carried out in the presence of the sultan in Yıldız Palace and the public were interested in the cinema, for many years Abdulhamid II did not allow the French to open a permanent film theater in Istanbul, as he was concerned about the influence of this novelty on the audience. In 1908, this changed. From this date, French Pathé Company not only concentrated on exporting machinery and film, but also started opening film theaters in representative markets. Pathé chose Sigmund Wienberg to carry out this work in Turkey in their name.25 As a result, Weinberg opened the first permanent cinema hall in Turkey on January 30, 1908; this was called the Cinema-Theater Pathé. Weinberg enabled the establishment of more permanent film theaters and his efforts contributed to making Istanbul the center of the Turkish cinema industry.26 The Pathé Cinema, which was relatively modern in appearance for the period, only operated for eight years under the management of Sigmund Wienberg; later this became the Belediye Sineması (municipal cinema).27 Starting with short-reel documentary and comedy films, after some time, Weinberg moved his films to the Beyoğlu Concordia.28

After opening the Pathé Cinema, Weinberg dominated the cinema market. He started to look for markets for the films and devices he was accumulating. He published and distributed fliers in French, Greek, Armenian and even in German in order to open cinemas in districts that were densely populated by non-Muslims.29 In a move against his rival Assaduryan, who was also involved in cinema activities in Istanbul and organized screenings separately for women and men, he started screenings in the mansions and schools. Some of the important institutions were Weinberg held screenings included Mekteb-i Sultanî (Galatasaray High School), İstanbul Sultanîsi (Istanbul Boys’ High School)30 and Darüşşafaka.31

These screenings helped to raise a young film fan. This was Ali Fuat Uzkınay (1888- 1956).32 This young man, an officer at Istanbul Boys’ High School, had a special interest in cinema.33 He met Sigmund Weinberg and quickly learned how to operate the projector.34 Promising to organize film screenings, Uzkınay persuaded the head of the school, Ebul Muhsin Kemal, to buy a screening device. While Uzkınay was taking over from Weinberg, he had Şakir Seden (1890-1967), a history teacher at the same school, select the films to be screened. Fuat Uzkınay and Şakir Seden carried out screenings from 1910 to 1914.

Ali Fuat joined the army as a reserve officer, and approximately three months after this the Ottoman State entered World War I. In November 1914, the Ottoman State declared its entry into the war by demolishing the Russian monument erected during the Turco-Russian War of 1877-1878 at Ayastefanos (Yeşilköy). Reserve officer Ali Fuat Uzkınay filmed the “Demolition of San Stefano Monument” and is remembered as the first Turkish filmmaker.35 In 1915, while Fuat Uzkınay was serving in the army, Sigmund Weinberg made another important move and took over running one of the most luxurious film theaters of the period, Cine Palace or Aynalı Sinema, named for the mirrors in the foyer.36

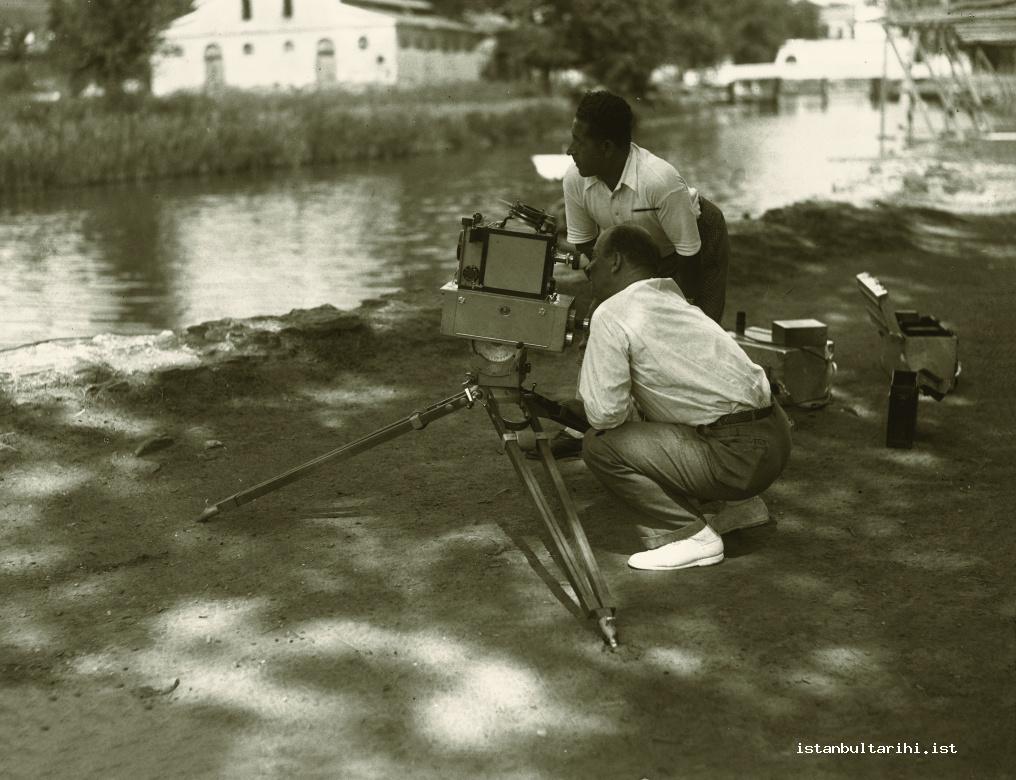

1915 witnessed another event that can be regarded as a milestone for Turkish cinema. In those days of World War I, the minister of war, Enver Pasha (1881- 1922), who was visiting the Ottoman ally Germany, watched footage that had been filmed by the German army. Impressed by these works, Enver Pasha ordered the establishment of a cinematography branch in the Ottoman Army. Upon his order, “the first official cinematography organization in an Islamic country”, the Merkez Ordu Sinema Dairesi (central army cinematography office - MOSD), was established in 1915 in Istanbul; Sigmund Weinberg was assigned as director and Ali Fuat Uzkınay was the assistant director.37 In the beginning, MOSD filmed documentaries. These films were about war and the official and private lives of the chief commander and the sultan.38 Some of the films shot by MOSD in Istanbul include Alman İmparatoru’nun Askerî Müzeyi Ziyareti (the visit of the German emperor to the military museum), which reflects the visit of German Emperor Wilhelm II and Austrian Emperor Karl to Turkey in 1917. In the last years of the war, in 1918, Abdülhamid’in Cenaze Merasimi (Abdülhamid’s funeral), Sultan Reşad’ın Cenaze Merasimi (Sultan Reşad’s Funeral), Vahdeddin’in Biat Töreni (Vahdeddin’s public allegiance ceremony) and Vahdeddin’in Kılıç Alayı (Vahdeddin’s girding of the sword ceremony).39

With these films, MOSD played a crucial role in the propaganda that was used to convince people that the war was in favor of the Central Powers.40 Weinberg’s duty in MOSD continued until August 29, 1916, when Romania abandoned its neutrality and declared war against the Ottoman Army. After this date, Weinberg was relieved of his duties, as he was now a citizen of an enemy state. However, he was not deported and his connection with MOSD continued, although non-officially.41 Weinberg was posted to the Galicia front by the central command, accompanied by photographer İbrahim Ferit Bey; they were to film the Ottoman soldiers and, at the end of this assignment, they both managed to return to Istanbul. Weinberg continued to live in Istanbul after being discharged from MOSD, and ran Aynalı Sinema, which was visited by dignitaries, in particular Enver Pasha.42

During wartime, some organizations were involved in cinematic activities in Istanbul in addition to MOSD. The first of these, Müdafaa-i Milliye Community, established in 1913 with the aim of improving relations between the army and the public, started cinematic activities in 1916 to increase their source of income. This community shot the first themed film of the Turkish cinema, Pençe (The Claw) and Casus (The Spy) in 1917.43 However, with the defeat in World War I in 1918, the Ottoman government had to sign the Armistice of Mudros; in accordance with the agreement, all transportation and means of communications were seized by the Allied powers. The film-making and screening devices of MOSD and Müdafaa-i Milliye organizations were part of this implementation. These two organizations transferred all cinematography tools and materials in their hands to Ma‘lûlîn-i Guzât-ı Askeriye Muavenet Heyeti (commission of war veterans and disabled) in 1919, to prevent these devices from being seized. The Ma‘lûlîn-i Guzât-ı Askeriye Muavenet Heyeti started making films after taking over. Fuat Uzkınay maintained his cinematographic activities after leaving the army upon the signing of Armistice of Mudros and started filming the first resistance against the occupation forces.44

The first censorship regarding the screening of motion pictures was imposed on Mürebbiye (The Governess - 1919) in Istanbul; the city was now under occupation by Allied powers. Adapted from the novel of the same name by Hüseyin Rahmi Gürpınar (1864-1944), the role of the French governess was played by the Russian actress, Madam Kalitea (Aristea Kalinea); the film was made on behalf of the Ma‘lûlîn-i Guzât-ı Askeriye Muavenet Heyeti by the director Ahmet Fehim. Due to her role in this film, Madam Kalitea was called “the first femme fatale of Turkish cinema.”45 As said above, when the film was released, Istanbul was an occupied city, due to the Ottoman State being defeated in World War I. The commander of the French occupation forces, General Franchet d’Espèrey (1856-1942) was rattled to see the Governess Anjel, shown as a lascivious French woman with loose morals, on the screens of film theaters of Istanbul; he banned the screening of the film on the grounds that the French were being humiliated.46

The second time Turkish cinema was censored was once again by occupation forces, as had been the case with The Governess. Adapted from the novel Nur Baba by Yakup Kadri (1889-1974), produced by the Ma‘lûlîn-i Guzât-ı Askeriye Muavenet Heyeti and directed by Muhsin Ertuğrul (1892-1979) in 1922, the screening of the film Boğaziçi Esrarı-Nur Baba (The Bosphorus Mystery - Nur Baba) was also banned by the occupation forces. In this film, the story of a Bekhtashi sheikh who was abusing his lodge by using it as a sex trap was developed as the theme. Occupation forces used Bekhtashi protests as an excuse for banning the film.47

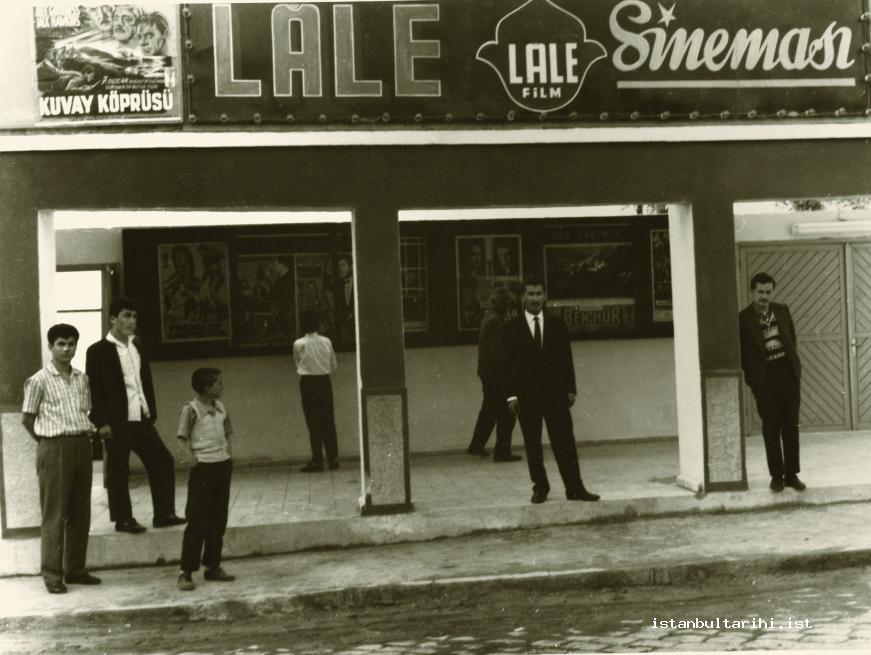

Istanbul’s distinguished role in the cinema continued until 1923, when the Republic was proclaimed and Ankara was declared the capital. Although Istanbul lost its identity as the capital city, it was still the commercial and cultural/art center of the country. Therefore, the infrastructure necessary for the development of the cinema was to be found in Istanbul. In the 1920s, important film production companies were either in operation or in founding stages. For example, Kemal Film, established by brothers Mehmet Kemalettin (1888-1941) and Mehmet Şakir Seden (1890-1967) in 1919 in Sirkeci to import films, started to produce films in 1922 upon the suggestion of Muhsin Ertuğrul. Opera Film was founded by Mehmet Rauf Sirman, his son Balcı Naim, and Vassilaki Papayonopulos in 1924. With the takeover of Elhamra Cinema in 1922, the İpekçi family started İpek Film in 1928. Lale Film was founded by Cemil Filmer and his brother Tevfik Bey in the same year, and Ha-Ka Film, established by Halil Kamil Bey in 1929, started to produce films in 1938. The administrative centers of most companies that were operating during this period were in Galata or Beyoğlu.48

The period of Turkish cinema between 1923 and 1939 is known as “the era of theater actors”. The reason for this is producers, actors and other officials involved in cinematic activities during this period were generally theater professionals assigned by the Darülbedayi staff; their theatrical background can be seen in their films. Darülbedayi was established in 1914 and was affiliated with the Istanbul Municipality in April 1931; it was renamed İstanbul Şehir Tiyatrosu (Istanbul City Theatre) in 1934. Muhsin Ertuğrul made his mark during this period as a director. Muhsin Ertuğrul was the person who gave direction to and shaped this seventeen-year period of Turkish cinema.49 He took on directing, scriptwriting and producing a number of films including, Ateşten Gömlek (Shirt of Flame - 1923) Kız Kulesi’nde Bir Facia (A Disaster in the Maiden’s Tower-1923), İstanbul Sokaklarında (On the Streets of Istanbul-1931), Bir Millet Uyanıyor (A Nation is Awakening-1932), Aynaroz Kadısı (The Judge of Aynaroz-1938) and Bir Kavuk Devrildi (A Turban is Overturned-1939).

When in Istanbul, President Mustafa Kemal Atatürk went to the film theaters in Beyoğlu at every available opportunity. For example, he saw The Vagabond King starring Dennis King and Jeanette MacDonald on December 3, 1930 at Elhamra Cinema; Gallipoli, adapted from an English documentary, on January 22, 1932 at Opera Cinema; The Congress Dances starring Lilian Harvey and Henri Garat on February 23, 1932, and Révolte dans la prison starring Charles Boyer and Mona Goya on September 16, 1932 in Glorya Cinema.50After watching Gallipoli at Opera Cinema on January 22, 1932, during a conversation with the mangers of the theater, Mehmet Rauf and Cemal, Mustafa Kemal asked why the audience was so small. They told him that taxes were the most important problem not only for them, but also for the other filmmakers and added that the public could not come to the cinema due to the high ticket prices. In response to this, Atatürk created a tax reduction, giving an order to the finance minister of the period, Fuat Ağralı, to make things easier for cinema managers and theater owners.51

Following the era of theater actors, the era between 1939 and 1952 is referred to as the “transition period” in the history of Turkish cinema. As the Second World War was going on during this period (1939-1945), cinema activities were adversely affected. Although both European and American films were being imported to Turkey before the Second World War, now, because of the war, only American and Egyptian films could reach Turkey via Egypt.52 Very few films were produced during this period in Turkish cinema; however, musical melodramas imported from Egypt were watched with interest by a considerable number of Turks. In the 1930s, the genre of music that is called Türk sanat müziği (Turkish artistic music) was banned due to fact that it included Arabic influences; for this reason Egyptian films became popular with a large sector of society. In the 1940s, Egyptian films were banned; however, the influence of these films on Turkish cinema and music, to some extent, continued.53

In 1939, Turkish cinema was still under the influence of the era of the theater actors; at this time, a camera would be placed in front of the stage and a play would be filmed from beginning to end. In other words, no definite separation from the theater tradition was accomplished. In the thirteen-year period between 1939 and 1952, Turkish cinema tried to form a more cinematic language by breaking itself off from the influence of theater.54 In the era of the theater actors, the audience had become conditioned to accept bad films as they got used to films mimicking the theater performance. This existing audience became an important problem that needed to be taken into consideration for the “Transition Period” of filmmakers.55 Taş Parçası (Piece of Stone), Yılmaz Ali and Kıvırcık Paşa by Faruk Kenç (1910-2000) can be regarded as the start of the Transition Period. Frequent visits of youngsters to bars to dance in Yılmaz Ali is regarded as an attempt to reflect Istanbul as a modern city. The exterior shots of the film were made in Rumelihisarı, Aşiyan and along the Bosphorus.56 Making his entrance into the world of cinema with these films, although there is a certain lack of skill in Kenç’s cinematic language, it displays less theatrical influence than that of Muhsin Ertuğrul. Kenç is the first director to shoot his films silently and add dubbing later on.57 In this period, with the departure from shooting sound films and the formation of the dubbing industry some Egyptian films were translated into Turkish and shown as if they were Turkish films.58

Due to the limited opportunities that the government could offer, young artists who were interested in the cinema went to countries such as Germany, France, America or Russia in the 1930s in order to receive education and gain experience. These young people returned to Turkey with the outbreak of the Second World War and aimed to put the knowledge and experience they had gained into practice. However, due to the limited means and the rivalry in the cinema sector in Turkey, they had difficulty in finding a place in the production of films.59 1948 was a fateful year for the Turkish cinema. The entertainment tax which was collected by municipalities for making films was reduced. This reduction meant domestic films had a tax that was less than half that of foreign films imposed on them; this in turn enabled cinemas that were showing domestic films to stay ahead of the game and compete with the cinemas that showed foreign films. As a result, cinemas began to prefer to show domestic films and the number of domestic films produced in Turkey increased rapidly.60

The following period, referred to as the “era of the cinematographers”, is considered to have started in 1952. Lütfi Ömer Akad (1916- 2011), who we can consider to be the director who started this era, stands out as the first Turkish director to use cinematic language appropriately in his films Kanun Namına (In the Name of the Law) and Yalnızlar Rıhtımı (The Quay of the Lonely Ones-1952).61 In the 1950s, Turkish cinema made considerable progress. The political transition to a multi-party system in 1950, which was a milestone in Turkish political and social life, played a major role in this progress. Production and consumption relationships in the country changed with the development of the liberal market economy in which the closed structure of the provinces were destroyed; a large-scale immigration started from rural areas to the cities. In the meantime, in accordance with the demands of the growing cinema audience, a new generation of directors from outside the theater emerged and they adopted a more developed approach to cinema as compared to the previous era. As a result, the Turkish popular cinema, known as Yeşilçam, was born; this was to be dominant in the cinema sector until the mid-1980s.62 In the 1950s, the entrepreneurs who saw cinema as a good source of income, one which required a small investment, filled Yeşilçam lane in Beyoğlu and the surrounding areas with their offices.63

The directors of the 1950s produced a variety of crime melodramas in order to realistically represent Istanbul as a modern city that included human debauchery. For example, Lütfi Ömer Akad’s films Kanun Namına (In the Name of the Law -1952) and Öldüren Şehir (The Murderous City-1953) were products of this approach.64 In the first scenes of Kanun Namına, during the police chase Büyükada, Golden Horn Dockyard, Süleymaniye Mosque, Beyazıt Square, Grand Bazaar, Nuruosmaniye Mosque and Sirkeci appear on the screen realistically.65 Films that are set in the suburbs can be seen through to the end of the 1950s, especially in Memduh Ün’s (b. 1920) Üç Arkadaş (Three Friends-1958), one of the most important examples of such films.66 During these years, Istanbul suburbs provided a setting for these films, presenting a city where internal immigration resulted in squatter settlements and infrastructure problems, and one where cultural conflicts began to be experienced.

The influence of the different movement of ideas in Turkish cinema started to be seen after 1960.67 There are many ideas, both positive and negative, expressed by various circles regarding the influence of the May 27, 1960 military coup on Turkish political and cultural life. Leaving all of this aside and only taking into consideration the influence of the coup on Turkish cinema, it can be seen that its effect generally was interpreted positively. “In fact, a coup leading up to the start of a positive process for the cinema of the country seems like a paradox, but the May 27 coup has a positive meaning for Turkish cinema…”68 Based on the principle of a social state, the 1961 Constitution resulted in the opening up of new horizons in the country and became a source of inspiration for artists and intellectuals.69 During this period, Turkish cinema handled more different topics than it had in previous periods, especially when it started to address social problems.70 In Metin Erksan’s (1929- 2012) Acı Hayat (Bitter Life-1962), while new settlements constructed in the Istanbul during the urbanization process of the 1960s are reflected, both modern and traditional aspects are portrayed. Ertem Göreç’s (b.1931) Karanlıkta Uyananlar (Those Awakening in the Dark-1964), which is the first film about workers and strikes in Turkish cinema, brings Istanbul’s factories and slums to the screen.71 Halit Refiğ’s (1934-2009) Gurbet Kuşları (Birds of Exile-1965), adapted from Orhan Kemal’s novel of the same name, is regarded as the first film about immigration in Turkish cinema that reflected the immigration problems of the country.72 As in many Turkish films before and after this film, Haydarpaşa Station is brought to the screen as the symbolic location of immigration.

Amidst the political atmosphere caused by the 1961 Constitution, the first idea movement reflected in the films was that of social realism.73 Turkish cinema was under the influence of American social realism, Italian new realism and the socialist realism of the Soviet Union. The aim of the movement was “producing films which could demonstrate the surface of the realities in society.”74 Turkish cinema in the early 1960s clearly reflects the changes going on in society and narrates the struggle of the individual vividly via these new parameters. In a sense, the cinema mirrors society, touches on the problems and offers solutions.75

The social realist movement became influential in the Turkish cinema between 1960 and 1965.76 Two crucial events can be seen to have caused the influence of this movement to decrease after 1965. One of these was the accession of the Adalet Partisi (Justice Party) to power with the 1965 elections. Maintaining a liberal political view, the Adalet Partisi was opposed to Marxism. Therefore, the control of censorship that had been loosened towards leftism in the previous five years was now under the control of the Adalet Partisi. The second event was a conflict between directors who represented social realism and critics who defended this movement; this, in turn, led to directors such as Halit Refiğ, Metin Erksan and Duygu Sağıroğlu (b.1932) abandoning Marxism.77

The reason for this conflict can be summarized as follows: These directors turned towards the idea of nationalization and overcoming the West through indigenous efforts; in fact, this movement had started with Kemal Tahir (1910-1973) in literature. They felt that a Marxist type of class struggle did not exist in Ottoman Turkish society. Their statements on this topic soon led them into conflict with scientific socialists. When Refiğ embarked on the cinema, he claimed that it was supported with the money of the public and therefore there was no capitalist structure. With the term “public cinema” that he used, he attempted to refute the term “populism” as understood by the Marxists. Both sides levelled bitter accusations at one another in a session held in 1966 in the halls of the Sinematek Association, the founders of which were artists such as Onat Kutlar (1936-1995), Şakir Eczacıbaşı (1929-2010), Muhsin Ertuğrul and Nijat Özön (1927-2010).78 As a result of the arguments, as some of the representatives of the social realism movement turned towards a nationalist mindset, this movement was split in two, and this in turn led to the emergence of a revolutionary cinema movement based on Marxism and represented by Yılmaz Güney (1937-1984), and the national cinema movements which aimed to narrate the national culture of Turkish people via cinema and was represented by Metin Erksan and Halit Refiğ. The Milli (national) cinema movement, represented by director Yücel Çakmaklı, who produced his first work Birleşen Yollar (Cross Roads-1970), followed these movements.79

In the 1970s, Turkey had to cope with a series of political and economic problems, including the March 12, 1971 Memorandum, the Cyprus War, petrol shortages, political conflicts in the universities and on the streets and domestic terrorism. The cinema sector had its share of trouble from these struggles and, although there had been a steady increase in films until the early 1970s, a slowdown now occurred in film production. In addition, the television entering houses in the 1970s was an important turning point for Turkish cinema and Yeşilçam tried to overcome this period of crisis with sex films.80 In the early 1970s, three of the most important films of the Turkish cinema, Lütfi Ömer Akad’s Gelin (The Bride-1973), Düğün (The Wedding-1974) and Diyet (Blood Money-1974), were released; in these films, Akad addresses problems such as internal migration to Istanbul, urbanization, working life and the modernization of Turkish women. These films focus on families who arrived respectively from Yozgat, Şanlıurfa and Afyon, and who remained caught between the values of the provinces and city culture of Istanbul. The films all narrate the hardships that the families confronted in their jobs, while the economic, social and cultural changes experienced in the Istanbul of the period are portrayed realistically on the silver screen.81

Istanbul was the setting of numerous comedies shot in the 1970s as well. We see the characters coming to Istanbul in order to hunt for treasure in locations including Haydarpaşa Station, Taksim Square, Beyoğlu and İnönü Stadium in Salak Milyoner (Millionaire Fool-1974) directed by Ertem Eğilmez (1929-1989). In Ertem Eğilmez’s comedy Hababam Sınıfı (Chaos Class-1974) and its sequels, in addition to many other locations in Istanbul, we see Validebağ Adile Sultan Pavilion, which functions as a teaching and cultural center today. In the romantic comedy Ah Nerede (1975) directed by Orhan Aksoy (1930-2008), there are indications of the right-left conflict in Istanbul, as was the case in many parts of the country in the 1970s. Zeki Ökten’s (1941-2009) Kapıcılar Kralı (The King of Doormen-1976) which was filmed in Güneşli Street in Cihangir, reflects life in an apartment building and neighborhood relations in Istanbul through the apartment residents from different classes and occupational groups. The romantic comedy Sultan (1978) by Kartal Tibet (1938) highlights the internal migration, strikes, union problems and slum life of Istanbul.82

The 1980s, starting with the September 12, 1980 military coup, was the onset of a rough time for Turkish cinema; this period lasted until the mid-1990s. The embargo imposed by Hollywood production companies on film importers in Turkey on grounds of loan defaults caused a major crisis in the importation and screening of films for the Turkish cinema sector. Following this development, two American distribution companies, Warner Bros (WB) and United International Pictures (UIP) opened their own offices in Turkey and, after legal arrangements, got into the video cassette and film markets in the 1980s. The opening of improved, high quality film theaters introduced by these companies brought along the general release of foreign films simultaneously with the USA and Europe. Although positive in terms of the increase in quality of the cinemas, this development caused the Turkish cinema sector to fall under the hegemony of American companies.83 As a result of the influence of American companies in the sector, Turkish films had difficulty finding film theaters and a new generation of audiences, conditioned by American action films, showed a lessening interest in Turkish films.84 The audience numbers for domestic movie decreased from 58,000,000 in 1978 to 20,000,000 in 1986, to 5,600,000 in 1990 and to a low of 300,000 in 1994.85

With TV becoming a major means of entertainment in the 1980s, an important development for the cinema sector was the home VCR. However, following a period of depression due to the development of the video sector, it was this same sector that helped Turkish cinema came out of this depression. The production aspect of the film industry revived for a temporary period with the developing video sector’s financial support. However, this revival was temporary; color television and an increase in channels, and greater access to videos meant that people stayed home instead of going to the cinema; all these in addition to the difficulty of finding cinemas that would show Turkish films resulted in a depression in the sector. During these years, the number of directing and production companies fell sharply and the technical infrastructure weakened. Studios started to close down and cinemas started to become commercial buildings. These developments which were experienced in Turkish cinema occurred for the most part in Istanbul, the center of Turkish cinema. Hundreds of summer cinema locations were replaced by commercial buildings, apartments, parking garages and shopping centers.86

Çiçek Abbas (1982), directed by Sinan Çetin (b. 1953-), is one of the most striking examples illustrating how Istanbul was reflected on the silver screen in films produced in the 1980s. The film focuses on minibus drivers in a period when dolmuş transportation became popular in Istanbul. In Nesli Çölgeçen’s (b. 1955) Züğürt Ağa (The Broke Agha-1985), a village agha’s efforts to adjust to the conditions of city life after migrating to Istanbul from the southeast is portrayed. Muhsin Bey (1987), by Yavuz Turgul (b. 1946), focuses on a scrupulous Istanbul gentleman, the entrepreneur Muhsin Bey, and his efforts to maintain his simple life against the degradation of city culture, associated with the popularization of arabesque music.87

From 1990 on the state started to implement policies to provide financial support for cinema projects. The problems in Turkish cinema, such as support by the government for the cinema, were discussed in the Turkish Cinema Council, held in the same year. The downward trend of Turkish cinema in the 1990s started to turn upwards when films such as Eşkıya (The Bandit-1996) by Yavuz Turgul, İstanbul Kanatlarımın Altında (Istanbul beneath My Wings-1996) by Mustafa Altıoklar and Ağır Roman (Cholera Street-1997) surpassed foreign films at the box office. Eşkıya relates the story of an old man who came to Istanbul to find his beloved after serving many years in prison on charges of banditry. İstanbul Kanatlarımın Altında tells of the flight of Hezarfen Ahmet Çelebi from Galata to Üsküdar with his homemade wings in the seventeenth century while Cholera Street is set in the dark and tangled streets of Tarlabaşı in the 1970s. Film theaters that offer high quality sound, images and service, located in shopping centers, a facility which increased in number, particularly in Istanbul, became one of the factors that attracted the public to the cinemas once again. Another factor in the increase was that Turkish TV series reminded people of Turkish films and this helped the audience become accustomed to watching films.88

The 2000s were a landmark in Turkish cinema thanks to the positive developments in the Turkish economy and the growth in the advertising and television sectors. The income derived from Turkish TV series watched not only in Turkey, but in many countries around the world, especially in the Middle East and the Balkans, provided support for the cinema sector. Eventually, Turkish cinema reached an important stage by achieving greater box office success than American films with Conquest 1453 and a number of Turkish directors winning awards in prestigious global film festivals, in particular, Nuri Bilge Ceylan (b. 1959). In 2013, when this text was written, Istanbul still maintains its characteristic as the leading city of Turkish cinema. Istanbul is still the film hub with a myriad of cinemas, the highest audience numbers and a location that attracts both domestic and foreign producers. Although Beyoğlu is still an important district for Turkish cinema, it has lost its unique nature in this field. Film companies have now moved out of Beyoğlu and scattered to various districts of Istanbul, in particular Beşiktaş and Şişli.89

Among the films to be considered in terms of representing Istanbul in the cinema, Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s Uzak (Distant) (2003) is the most important one from the 2000s. It presents the events between Yusuf, who comes to Istanbul with the hopes of finding a job, and his relative, the photographer Mahmut, with whom he stays, by depicting the conflict between the urban dweller and country people and touching upon the problems experienced by unskilled workers.90 The height of aesthetics in the representation of Istanbul on the silver screen is Sevmek Zamanı (A Time to Love) (b. 1965) directed by Metin Erksan. Conquest 1453 (2012) by Faruk Aksoy (b. 1964) tells of the conquest of Constantinople by the Turks, as the name suggests. With a $17,000,000 budget and an audience of more than 6,000,000, Conquest 1453 was successful in the visual effects, set design and costume; this film encouraged filmmakers to carry out grand productions in Turkish cinema. However, the acting and scenario were only of average quality.

Istanbul’s Cinemas

The first full-time cinema in the Ottoman State, Cinema Pathé, was opened on January 30, 1908, by Sigmund Weinberg; this was located in the place of the old comedy section of the City Theater in Tepebaşı. (In the 1980s, TÜYAP Istanbul Exhibition Hall was opened here. Now this building is being used as a studio by Turkish Radio Television Corporation).91 It was followed by Orientaux opened in 1911 in Beyoğlu, and then Central and İdeâl, which were opened in 1912, Lion opened in Galata in 1913, Gaumont on İstiklal Street, Artistic in Şişli, Americain and Parlant in Beyoğlu, and an unnamed cinema in 1914 in the Historical Peninsula. Other cinemas were Apollon in Beşiktaş, Ahali, Luxembourg (formerly Gaumont Cinema, later Glorya and Saray Cinemas), Akaretler (another name for Apollon and Ahali cinemas), Éclair in Beyoğlu, Majestic in Yüksekkaldırım, Emperyal in Şehzadebaşı (former Fevziye Coffee House, later Milli, Güneş and Türk cinemas), Türk and Ali Efendi in Sirkeci, Erenköy in Erenköy, Palas on Divanyolu (later Divanyolu), Milli (former Emperyal), Donanma in Şehzadebaşı (later Müdafaai Milliye), Ertuğrul in Şehzadebaşı and Kemal Bey in Sirkeci. Gökmen mentions 260 cinemas for the period between 1908 and 1950; however, some of this number were cinemas that continued from another cinema under a new name.92

The active cinemas in Beyoğlu in 1921 were as follows: Magic, Etoile, Cosmograph, Russo-Americain, Luxembourg, Cine Palace, Eclair, Central, Orientaux, Cine Amphi and Taxim Garden. Cine Amphi, with 1,030 seats, and Magic, with 1,005 seats, had the highest seating capacity. Taxim Garden was an open air cinema for 400 people.93 Electra was opened by the İpekçi Brothers in Beyoğlu in 1921 (later renamed Alkazar in 1925 and closed down in 2010) and Elhamra, opened in 1922 (closed down after the fire in 1999), were among the important cinemas of the period.94

In the early years of the republic there were not even thirty cinemas in the city. These cinemas operated mainly in three districts: 1) in the region that is known as the Historical Peninsula or suriçi (at this time, this was the region that was meant when Istanbul was referred to), on both sides of the road between Şehzadebaşı and Sultanahmet, 2) in the area between Taksim Pangaltı and Tünel in Beyoğlu 3) Kadıköy (three cinemas) and Üsküdar (one cinema). In addition, during the summer months there were open-air cinemas set up in the gardens of mansions or in vacant lots.95 The first example of open-air cinemas is claimed to have been the Eski Osmanbey Bahçesi (old Osmanbey garden), which opened in 1913 on Şişli Halaskargazi Street. The number of open-air cinemas was 20 in 1949, 103 in 1958 and 143 in 1964. After reaching 188 in 1969, from the mid-1970s these cinemas started to close down quickly.96

Some of the old Istanbul cinemas are remarkable for their architectural features. In Kadıköy, in the early years of the Republic, Süreyya Cinema was an important architectural work with its glassed-in exterior hall, cavernous foyer, reminiscent of a magnificent hall, grand tier boxes, painstaking work on the front and rear façades and frescos on the ceiling and walls. Çemberlitaş Cinema in the Osman Bey Complex in Çemberlitaş was a cinema whose exterior architecture reflects the European neoclassic style during the reign of Abdulhamid II. The most magnificent cinema halls were in Beyoğlu; the hall of the Opera Cinema featured impressive architecture. Its two walls were decorated with frescos. The ceiling was decorated with colorful motifs and illuminated with three large chandeliers. Sümer Cinema (Artistic) was furnished according to the Cubist and Surrealist fashion that was popular in the 1930s and surrealist pictures were painted on the walls of the cinema. The ceiling was decorated with hundreds of star-shaped lamps, while a moon and the Milky Way were depicted on the sides of the stage.97 Important cinemas of the period such as Majik (Taksim Cinema), opened in 1920, Electra (Alkazar) in 1923, Lale in 1939, Saray in 1933, Elhamra in 1923, Ar (Sine Pop) in 1943, Yeni Melek in 1954, Artistik (Sümer, Rüya) in 1930 had to be closed down in the period from late 1990s through today, despite their importance with regards to Turkish cinema history.98

In the 1960s, the heyday of Turkish cinema, there was a dramatic increase in the number of cinemas in Istanbul. In 1966, 241 films were produced by Yeşilçam; in the following year, the number of cinema halls reached 320.99 In the period from the 1970s to the mid-1990s, as a result of a depression in Turkish cinema, the number of cinemas in Istanbul decreased to 89; 8 of these were summer cinemas.100 As of 2010, there are 501 cinemas in Istanbul, with a total seating capacity of 74,606. The film theater chains have a 68% share of the market and small business owners receive a 32% share.101 Considering that the total number of cinemas in Turkey was 1,917 as of 2011, Istanbul is an important center in terms of the number of film theaters.102

Istanbul Films

From the time that filming began in 1896 until 2013 a myriad of films have been set in Istanbul. Indeed, almost 40 films that were produced between 1922 and 2004 include the word “Istanbul” in their title. Muhsin Ertuğrul’s İstanbul’da Bir Facia-ı Aşk (A Love Tragedy in Istanbul-1922) and İstanbul Sokaklarında (On the Streets of Istanbul-1931), Aydın Arakon’s İstanbul’un Fethi (Conquest of Istanbul-1951), Lütfi Ömer Akad’s Görünmeyen Adam İstanbul’da (Invisible Man in Istanbul-1955), Metin Erksan’s İstanbul Kaldırımları (Pavements of Istanbul-1964), Halit Refiğ’s İstanbul’un Kızları (Girls of Istanbul-1964), Atıf Yılmaz’s Ah Güzel İstanbul (Oh Beautiful Istanbul-1966), Ömer Kavur’s Ah Güzel İstanbul (Oh Beautiful Istanbul-1981), Mustafa Altıoklar’s İstanbul Kanatlarımın Altında (1995) and Anlat İstanbul (Istanbul Tales-2004) directed by Ümit Ünal, Kudret Sabancı, Selim Demirdelen, Yücel Yolcu and Ömür Atay are among these films.103

There are approximately thirty-five films that include the names of districts, neighborhoods or locations in Istanbul in their title. Boğaziçi Esrarı (Bosphorus Mystery) by Muhsin Ertuğrul, Beyoğlu Esrarı (Beyoğlu Mystery-1952) by Nuri Akıncı, Süleymaniyeli Ali (1962) by Osman Fahir Seden, Beyoğlu’nda Vuruşanlar (1966) by Ertem Göreç, Cibali Karakolu (Cibali Police Station) by Hulki Saner, Balatlı Arif (1966) by Atıf Yılmaz, Beyoğlu Güzeli (Beyoğlu Beauty-1972) by Ertem Eğilmez, Beyoğlu’nun Arka Yakası (Back Streets of Beyoğlu) (1986) by Şerif Gören, and Laleli’de Bir Azize (A Saint in Laleli) by Kudret Sabancı are among these films.104

Istanbul is a city that has attracted the attention of foreign as well as domestic filmmakers, as it includes historical and touristic destinations. In this context, the first film that should be considered is Estambul (Istanbul), directed by Joseph Pevney in 1957. The film, featuring Errol Flynn, Cornell Borchers and John Bentley, opens with images of Sultan Ahmet and the Golden Horn. It also includes Ortaköy Mosque, Galata Bridge and the beauties of the Bosphorus, ending with aerial views of the Golden Horn. In 1963, Istanbul hosted a James Bond film. Most of the film, From Russia with Love, directed by Terence Young and starring Sean Connery, was filmed in Istanbul. Galata Bridge, the Grand Bazaar, Nuruosmaniye Mosque, Blue Mosque, and Firuzağa Mosque were outdoor locations that were used. In addition, Basilica Cistern and Cistern of Philoxenos, Hagia Sophia Museum, Saliha Sultan Fountain and scenes from Beşiktaş and Üsküdar were also included.105

Directed by Jules Dassin, starring Melina Mercouri, Peter Ustinov and Maximilian Schell, Topkapı (1964) represents the modernized face of the city with the Hilton Hotel, as well as showing Galata Bridge, various historical mosques, wooden houses and cobblestoned streets. Directed by Sidney Lumet in 1974, starring Ingrid Bergman, Sean Connery and Anthony Perkins, Murder on the Orient Express in general presents a negative image of Istanbul. With sheep grazing by the pier, pushy salesmen in ragged clothes and an emphasis on bad food, the image of a backward Istanbul is projected in the film, which was set on Salacak Pier and Sirkeci Station and depicts the Istanbul Strait with scenes from Üsküdar and Kadıköy.106

In the film Zombie and the Ghost Train starring Silu Seppälä and Majo Leinonen, directed by Mika Kaurismäki in 1991, Yeni Cami in the historical district of Eminönü and Galata Bridge were the filming locations. Im Juli (In July) (2000), directed by Germany-based Turkish director Fatih Akın, stars Christiane Paul and Moritz Bleibtreu and presents scenes from Harem, Salacak and Ortaköy as well as Maiden’s Tower, Ortaköy Mosque and the Bosphorus Bridge. Famous action film actor Jackie Chan was the main character Bei in Accidental Spy (2001), directed by Teddy Chan, and many historical locations were used, such as Hagia Irene Church, Basilica Cistern, the Grand Bazaar and Haydarpaşa Train Station.107

Towards the end of Monsieur İbrahim et les Fleurs du Coran (Monsieur Ibrahim and the Flowers of the Qur’an) (2003) directed by François Dupeyran, starring Omar Sharif and Pierre Boulanger, we see scenes from Istanbul, however, although being filmed in 2003, it represents the Istanbul of the 1960s. The waters of the Bosphorus, Sarayburnu, Eminönü and Galata Bridge are shown in the film. Istanbul’s significant religious structures, such as Hagia Sophia Museum and Blue Mosque, are shown in keeping with the theme.108 Directed by Charles Winkler in 2005, starring Connor Tracy and Neil Hopkins, almost all of The Net 2.0 was set in Istanbul. Taksim, Sultanahmet, Süleymaniye and Ortaköy are the districts that appear most in the film, along with the historic and touristic areas of Galata Tower, Topkapı Palace, Süleymaniye Mosque, Valens Aqueduct and Hagia Sophia.

Directed by Olivier Megaton (released in 2012) and starring Liam Neeson, Famke Janssen and Maggie Grace, Taken 2 is one production completely set in Istanbul. In the film, which was mostly filmed in the Historical Peninsula, scenes from Balat, Kadıköy, Haydarpaşa and the Bosphorus are shown together with the historical mosques of Istanbul and Galata Bridge. The film was highly criticized as it presented the most derelict locations of Istanbul and showed police cars as Fiat 131 cars, the production of which had been terminated in Turkey in 1985. In 2012, Istanbul became the set for another James Bond film. Directed by Sam Mendes, starring Daniel Craig, Javier Bardem and Naomie Harris, a substantial part of the filming was done in Eminönü Square, the Grand Bazaar and Beyazıt. This film, too, was criticized for not representing Istanbul adequately.

Istanbul Film Festivals

According to data 2010 data, twenty-seven film festivals are organized annually in Istanbul.109 Reviving cinema life in Istanbul, new filmmakers can introduce themselves to the sector and establish communication and business opportunities with foreign filmmakers; the most important of these festivals are: Uluslararası İstanbul Film Festivali (International Istanbul Film Festival), Uluslararası Randevu İstanbul Film Festivali (“International Rendezvous Istanbul Film Festival) organized by Türkiye Sinema ve Audiovisuel Kültür Vakfı (TÜRSAK - Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts), Uluslararası Sinema ve Tarih Buluşması Film Festivali (International Encounter of Cinema and History Film Festival) and Mini Bank Uluslararası Çocuk Filmleri Festivali (Mini Bank International Children’s Film Festival) by Turkish Foundation of Cinema & Audiovisual Culture (TÜRSAK), Filmmor Kadın Filmleri Festivali (Filmmor Women’s Film Festival) by Filmmor Kadın Çevre Kültür ve İşletme Kooperatifi (Filmmor Women, Environment, Culture and Business Cooperative), İstanbul Uluslararası 1.001 Belgesel Film Festivali (Istanbul International 1001 Documentary Film Festival) presented by BSB Sinema Eseri Sahipleri Meslek Birliği (Professional Association of Owners of Cinematic Works) and İstanbul Uluslararası Kısa Film Günleri (Istanbul International Short Film Festival), organized by İstanbul Fotoğraf ve Sinema Amatörleri Derneği (İFSAK - Istanbul Amateur Photography and Cinema Society).

The most renowned of the festivals held in Istanbul is the “International Istanbul Film Festival” organized by İKSV. This festival started as a “film week” in which six films were screened as part of the “Arts and Cinema” theme. This event was part of “International Istanbul Festival”, and started in 1982. As part of the Istanbul Festival, this event was called Uluslararası İstanbul Sinema Günleri (International Istanbul Cinema Days). In 1984, this became a separate organization, Sinema Günleri (Cinema Days), and was held every April. In 1985, another section was added to the program; this consisted of one international and one national competition, with Michael Radford receiving the first Altın Lale (Golden Tulip), that is, the grand prize of the festival for his film 1984. Sinema Günleri was renamed Uluslararası İstanbul Film Festivali after being accredited by the International Federation of Film Producers Associations (FIAPF) in the category of “a competitive specialized festival” in 1989.110

To celebrate its 25th anniversary in 2006, the Uluslararası İstanbul Film Festivali launched an event called Köprüde Buluşmalar (Meetings on the Bridge) as a platform to bring together Turkish filmmakers and European producers. As part of this platform, the Uzun Metrajlı Film Projesi Geliştirme Atölyesi (Feature-length Film Project Development Workshop) was begun in 2008; this workshop culminated in a prize. These activities were part of the festival and the goal was to create opportunities for co-productions by bringing together producers, directors, scriptwriters and agents both from Europe and Turkey in workshops and seminars. The part of the festival program entitled “Human Rights in the Cinema” was made into a competition in 2007; one of the films under this section received the Film Award of the Council of Europe (FACE) with the cooperation of the European Council and Eurimages. This award is only presented at the International Istanbul Film Festival. As the most comprehensive film festival in terms of the number of films screened, the International Istanbul Film Festival is one of the most popular film festivals, with an audience reaching 170,000 in 2007.111 In 2010, with 243 directors from 57 countries, the annual budget of the International Istanbul Film Festival was 1,300,000 euros.112

FOOTNOTES

1 Giovanni Scognamillo, Cadde-i Kebir’de Sinema, Istanbul: Agora Kitaplığı, 2008, p. 1.

2 Ali Özuyar, Devlet-i Aliyye’de Sinema, Istanbul: De Ki Yayınları, 2007, p. 33.

3 Süleyman Beyoğlu, “Osmanlı Sinema Tarihine Dair Bazı Bilgiler”, Simurg, no. 2-3 (2000), pp. 458-459.

4 Özuyar, Devlet-i Aliyye’de Sinema, p. 11.

5 Ali Özuyar, “Osmanlı’da Sinemaya Dair Sansür Notları”, Sinematürk, 2007, n. 7, p. 22.

6 Ayşe Osmanoğlu, Babam Sultan Abdülhamid, Istanbul: Selis Kitaplar, 2008, p. 72.

7 Agah Özgüç, Başlangıcından Bugüne Türk Sinemasında İlk’ler, Istanbul: Yılmaz Yayınları, 1990, p. 8.

8 Burçak Evren, Sigmund Weinberg: Türkiye’ye Sinemayı Getiren Adam, Istanbul: Milliyet Yayınları, 1995, p. 35.

9 Özgüç, Türk Sinemasında İlk’ler, p. 8.

10 Özuyar, Devlet-i Aliyye’de Sinema, p. 34.

11 Alim Şerif Onaran, Türk Sineması, Ankara: Kitle Yayınları, 1999, vol. 1, p. 11.

12 Özuyar, Devlet-i Aliyye’de Sinema, p. 34.

13 Özuyar, Devlet-i Aliyye’de Sinema, pp. 35-36.

14 Ali Özuyar, Sinemanın Osmanlıca Serüveni, Istanbul: Öteki Yayınevi, 1999, pp. 32-33.

15 Burçak Evren, “Sinemamızın İlk Türk Müslüman Kadınları”, Sinematürk, 2006, no. 1, p. 22.

16 Salih Diriklik, Fleşbek, Istanbul: Söğüt Ofset, 1995, vol. 1, p. 9.

17 Diriklik, Fleşbek, p. 9.

18 Erman Şener, Yeşilçam ve Türk Sineması, Istanbul: Kamera Yayınları, 1970, p. 15.

19 Özuyar, Sinemanın Osmanlıca Serüveni, pp. 34-35.

20 Özuyar, “Osmanlı’da Sinemaya Dair Sansür Notları”, p. 22; Özuyar, Devlet-i Aliyye’de Sinema, pp. 12-13.

21 Burçak Evren, “Türk Sinemasındaki İlk Sansür ya da Abdülhamid ve Sinema”, Türk Sinemasında Sansür, ed. Agah Özgüç, Ankara: Kolektif Kitle Yayınları, 2000; Serdar Öztürk, quoted from p. 138, “Türk Sinemasında İlk Sansür Tartışmaları ve Yeni Belgeler”, İletişim, 2006, no. 5, pp. 65-66.

22 Eric Jan Zürcher, Modernleşen Türkiye’nin Tarihi, Istanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 2006, p. 143.

23 Özuyar, “Osmanlı’da Sinemaya Dair Sansür Notları”, pp. 22-23.

24 Seda Bayındır Uluskan, Atatürk’ün Sosyal ve Kültürel Politikaları, Ankara: Atatürk Araştırma Merkezi, 2010, p. 487.

25 Evren, Sigmund Weinberg, p. 41.

26 Uluskan, Atatürk’ün Sosyal ve Kültürel Politikaları, p. 487.

27 Burçak Evren, Sigmund Weinberg: Türkiye’ye Sinemayı Getiren Adam, p. 51.

28 Uluskan, Atatürk’ün Sosyal ve Kültürel Politikaları, p. 487.

29 Evren, Sigmund Weinberg, p. 54.

30 Giovanni Scognamillo, Türk Sineması Tarihi: 1896-1959, Istanbul: Metis Yayınları, 1990, vol. 1, p. 20.

31 Evren, Sigmund Weinberg, p. 54.

32 Scognamillo, Türk Sineması Tarihi, vol. 1, p. 20.

33 Evren, Sigmund Weinberg, pp. 54-55.

34 Özgüç, Türk Sinemasında İlk’ler, p. 8.

35 Mustafa Gökmen, Eski İstanbul Sinemaları, Istanbul: İstanbul Kitaplığı Yayınları, 1991, p. 79.

36 Evren, Sigmund Weinberg, p. 69.

37 Uluskan, Atatürk’ün Sosyal ve Kültürel Politikaları, p. 489.

38 Onaran, Türk Sineması, p. 13.

39 Simten Gündeş, Belgesel Filmin Yapısal Gelişimi ve Turkiye’ye Yansımaları, Istanbul: Der Yayınları, 1991; Veli Boztepe, quoted from p.122: “1960 ve 1980 Askeri Darbelerinin Türk Siyasal Sinemasına Etkileri” (MA Thesis), Marmara University, 2007, p. 92.

40 Özuyar, Devlet-i Aliyye’de Sinema, p. 36.

41 Özuyar, Devlet-i Aliyye’de Sinema, pp. 40-41.

42 Özuyar, Devlet-i Aliyye’de Sinema, p. 41.

43 Nazım H. Polat, Müdâfaa-i Milliye Cemiyeti, Ankara: Kültür Bakanlığı, 1991, p. 102.

44 Boztepe, “1960 ve 1980 Askeri Darbelerinin Türk Siyasal Sinemasına Etkileri”, p. 93.

45 Mahmut Tali Öngören, Sinemada Kadın ve Cinsellik Sömürüsü, Ankara: Dayanışma Yayınları,1982, pp. 60-61.

46 Özuyar, “Osmanlı’da Sinemaya Dair Sansür Notları”, p. 24.

47 Öztürk, “Türk Sinemasında İlk Sansür Tartışmaları”, pp. 62-63.

48 Ali Özuyar, Türk Sinema Tarihinden Fragmanlar (1896-1945), Ankara: Phoenix Yayınevi, 2013, pp. 190-200.

49 Onaran, Türk Sineması, p. 20.

50 Gökmen, Eski İstanbul Sinemaları, p. 68.

51 Oğuz Makal, “Türk Sinemasının Uzun ve Yorucu Süreci ve Yarını İçin Düşünceler”, V. Türk Kültürü Kongresi: Cumhuriyetten Günümüze Türk Kültürünün Dünü, Bugünü, Geleceği: Sahne Sanatları, ed. Ömer Çakır, Ankara: Atatürk Kültür, Dil ve Tarih Yüksek Kurumu Atatürk Kültür Merkezi, 2005, vol. 11, p. 87.

52 Onaran, Türk Sineması, p. 34.

53 Ahsen Yalvaç, Türk Sineması ve Arabesk, Istanbul: Agora Kitaplığı, 2013, p. 15.

54 Şener, Yeşilçam, p. 23.

55 Şener, Yeşilçam, p. 23.

56 Semra Kır, İstanbul’un 100 Filmi, Istanbul: İstanbul Büyükşehir Belediyesi Kültür İşleri Daire Başkanlığı Yayınları, 2010, p. 16.

57 Rekin Teksoy, Rekin Teksoy’un Türk Sineması, Istanbul: Oğlak Yayıncılık, 2007, 27.

58 Bülent Vardar, “Türkiye’de Sinemanın Gelişimi ve Ulusal Sinema Tartışmaları”, Sinematürk, 2006, no. 2, p. 38.

59 Esin Berktaş, “1939–1950 Dönemi Türk Sinemasının Ekonomik, Politik, Toplumsal ve Kültürel Yapısı” (Dissertation in Art), Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University, 2008, p. 268.

60 Milli Sinema Açıkoturumu, Istanbul: Fatih Gençlik Vakfı, 1973, pp. 91-92.

61 Teksoy, Rekin Teksoy’un Türk Sineması, pp. 29-30.

62 Yalvaç, Türk Sineması, p. 17.

63 Teksoy, Rekin Teksoy’un Türk Sineması, p. 33.

64 Yalvaç, Türk Sineması, p. 20.

65 Kır, İstanbul’un 100 Filmi, p. 21.

66 Agâh Özgüç, Türk Sinemasında İstanbul, Istanbul: Horızon Internatıonal Yayıncılık, 2010, p. 100.

67 Diriklik, Fleşbek, p. 16.

68 Vardar, “Türkiye’de Sinemanın Gelişimi”, pp. 38-39.

69 Yalvaç, Türk Sineması, p. 24.

70 Vardar, “Türkiye’de Sinemanın Gelişimi”, pp. 38-39.

71 Kır, İstanbul’un 100 Filmi, pp. 38-45.

72 Özgüç, Türk Sinemasında İstanbul, pp. 140-141.

73 Mesut Uçakan, Türk Sinemasında İdeoloji, Istanbul: Düşünce Yayınları, 1977, pp. 10-11.

74 Ömer Menekşe, “Türk Sinemasında Din ve Din Adamı İmajı”, II. Uluslar Arası Dinî Yayınlar Kongresi, prepared by Ayfer Balaban, Ankara: Diyanet İşleri Başkanlığı, 2005, pp. 47-48.

75 Yalvaç, Türk Sineması, p. 25.

76 Vardar, “Türkiye’de Sinemanın Gelişimi”, pp. 38-39.

77 Uçakan, Türk Sinemasında İdeoloji, p. 36.

78 Uçakan, Türk Sinemasında İdeoloji, pp. 36-37.

79 Uçakan, Türk Sinemasında İdeoloji, pp. 10-11.

80 Evrim Töre Özkan, İstanbul Film Endüstrisi, Istanbul: İstanbul Bilgi Üniversitesi Yayınları, 2010, p. 38.

81 Ensar Yılmaz, “Gelin/Düğün/Diyet Filmlerinin Toplumsal Morfolojisi ve Politik Perspektifi”, Türk Sinemasında Sosyal Meseleler, edited by Ensar Yılmaz, Istanbul: Başka Yerler Yayınları, 2012, pp. 9-29.

82 Kır, İstanbul’un 100 Filmi, pp. 86-94.

83 Özkan, İstanbul Film Endüstrisi, p. 39.

84 Teksoy, Rekin Teksoy’un Türk Sineması, p. 73.

85 Giovanni Scognamillo, Türk Sinema Tarihi, Istanbul: Kabalcı Yayınevi, 2010, p. 368.

86 Özkan, İstanbul Film Endüstrisi, pp. 38-39.

87 Kır, İstanbul’un 100 Filmi, pp. 110-115.

88 Özkan, İstanbul Film Endüstrisi, pp. 41-42.

89 Özkan, İstanbul Film Endüstrisi, pp. 101-106.

90 Kır, İstanbul’un 100 Filmi, p. 154.

91 Evren, Sigmund Weinberg, p. 44.

92 Gökmen, Eski İstanbul Sinemaları, pp. 19-56.

93 Scognamillo, Cadde-i Kebir’de Sinema, p. 137.

94 Nijat Özön, Türk Sineması Tarihi 1896-1960, Istanbul: Doruk Yayıncılık, 2013, p. 40.

95 Burhan Arpad, “İstanbul’un Eski Sinemaları”, quoted by Burçak Evren, Eski İstanbul Sinemaları: Düş Şatoları, Istanbul: Milliyet Yayınları, 1998, p. 196.

96 Serpil Kırel, Yeşilçam Öykü Sineması, Istanbul:Babil Yayınları, 2005, p. 170.

97 Semavi Eyice, Eski İstanbul’dan Notlar, Istanbul: Küre Yayınları, 2009, pp. 42-46.

98 “Beyoğlu’nun Son Sinemaları”, 15.11.2013, http://www.radikal.com.tr/hayat/beyoglunun_son_sinemalari-1129418. The mistakes in the establishment dates of the cinemas have been rectified according to Mustafa Gökmen’s work.

99 Scognamillo, Cadde-i Kebir’de Sinema, pp. 82-83.

100 Evren, Düş Şatoları, p. 201.

101 Özkan, İstanbul Film Endüstrisi, p. 82.

102 Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu (TUİK), “Temel İstatistikler”, 15.11.2013, http://www.tuik.gov.tr/UstMenu.do?metod=temelist.

103 Özgüç, Türk Sinemasında İstanbul, pp. 29-32.

104 Özgüç, Türk Sinemasında İstanbul, pp. 34-36.

105 Kır, İstanbul’un 100 Filmi, p. 22, 42.

106 Kır, İstanbul’un 100 Filmi, p. 50, 82.

107 Kır, İstanbul’un 100 Filmi, p. 132, 150, 151.

108 Kır, İstanbul’un 100 Filmi, p. 158, 159.

109 Özkan, İstanbul Film Endüstrisi, p. 93.

110 “Festival”, 01.11.2013, http://film.iksv.org/tr/festival/tarihce.

111 “Festival”.

112 Özkan, İstanbul Film Endüstrisi, p. 94.