In the Ottoman Empire, just as in Europe, museums were an institution that helped support the move towards the modern era. However, in the Ottoman context museums followed a unique course; while structurally similar to museums in Europe, their roles developed in tandem with modernization in a way that was uniquely Ottoman.

Initial efforts by the Ottoman State to establish museums are generally traced back to 1846.1 That year, reports appeared in both the French and German press to the effect that Sultan Abdülmecid had ordered a museum to be organized in the capital and that archeological discoveries had been brought there from across the empire.2 There are also anecdotes in many sources that Sultan Abdülmecid learned about pieces of stone, discovered accidentally, on which the names of Byzantine emperors had been carved, and that he ordered these to be preserved.3 Taken together, these anecdotes and press reports indicate that a significant effort to gather and display archeological artifacts was underway at this date.

The first venue dedicated to the display of such objects was the former church Aya İrini (Hagia Eirene). Prior to 1846, the site had functioned as a depot for weapons seized during battles and for Christian relics that had been inherited from the Byzantine Empire. During the reign of Sultan Ahmed III (1703-1730), the name of the building was changed from İç Cebehane to Darülesliha, the site was renovated, and several exhibitions were held there. While these may in some measure have paved the way for the site’s transition from arms depot to museum, it must be noted that contemporary witnesses record that only a few chosen visitors, usually foreigners, were granted access. Moreover, those who were invited as guests were only permitted to see a very small part of the goods that were kept here.4

Mecma-i Âsâr-ı Atîka and Mecma-i Esliha-i Atîka

The exhibition Fethi Ahmed Pasha (d. 1858) organized at Aya İrini in 1846 played a decisive role in laying the foundations for later museum activities in the Ottoman Empire. This exhibition was referred to both as the Exhibition of Antique Weapons (Mecma-i Esliha-i Atîka) and as the Exhibition of Antique Objects (Mecma-i Âsâr-ı Atîka). As these names imply, both antique weapons and and other sorts of artifacts were on display. According to the memoirs of Gustave Flaubert and Théophile Gautier, who visited Aya İrini in 1851 and 1852 respectively,5 both collections were displayed simultaneously at Aya İrini. The main area of the church and the area surrounding the atrium housed the weapons display, while the atrium itself was devoted to the exhibition of archaeological findings.

Sermed Muhtar describes Fethi Ahmed Pasha’s efforts to remodel the interior of the building for the exhibition. He designed special display racks decorated with coats-of-arms for floor exhibits, and had other arrangements made so as to be able to fully utilize the available wall space, from floor to domed ceiling, for the display of weapons, military equipment, and other items. In order to fully transform Aya İrini into a weapons museum a number of additional renovations to the building itself were carried out, including the construction of a “sultan’s cell,” in the style of Louis XVI.6 One of the most alluring parts of the display was the section containing mannequins dressed as Janissary soldiers. When Gautier visited Aya İrini in 1852, these mannequins had been moved to a separate museum in the Hippodrome.

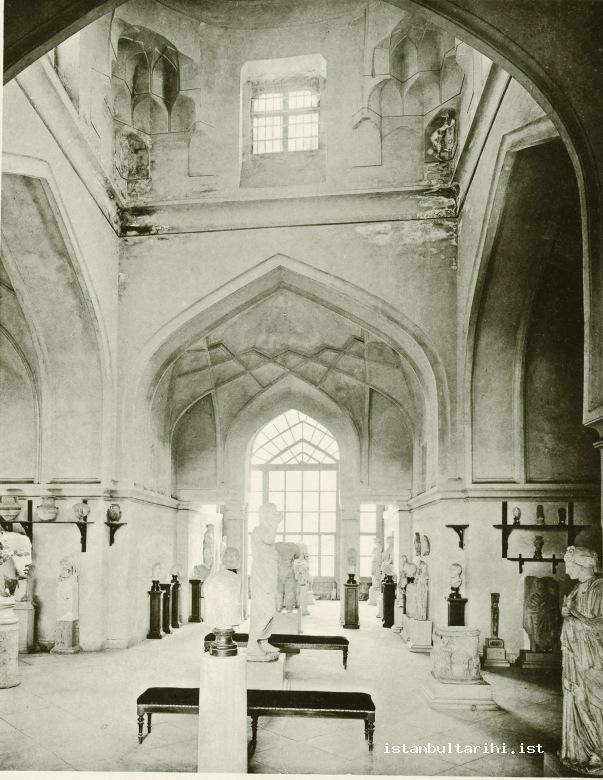

The archaeological items, far fewer in number than the military objects, were displayed in the church courtyard (Photo 1). The first catalogue describing the archaeological works in the museum was prepared by Albert Dumont in 1868.7 This work was prepared while Dumont was the director of the French Archaeological School in Athens, most likely during a visit he made to the Aya İrini collection while Istanbul, and published as an article in Revue Archéologique.8

Following the death of Fethi Ahmed Pasha, Aya İrini gradually ceased to function as a museum. During the Ottoman-Russian War (1877-78) it was once again put to use as an arms depot for the military, and though the interior of the building was not altered, the venue was closed to visitors.

Elbise-i Atîka Museum

In 1852, the Janissary mannequins that had been part of the display at Aya İrini were moved to a building in the Hippodrome, though why these objects were moved to a separate museum is not known. The new museum was a wooden building, adjacent to the structure known as the Mehterhane, located in the first courtyard of the İbrahim Paşa Palace, facing the square.9

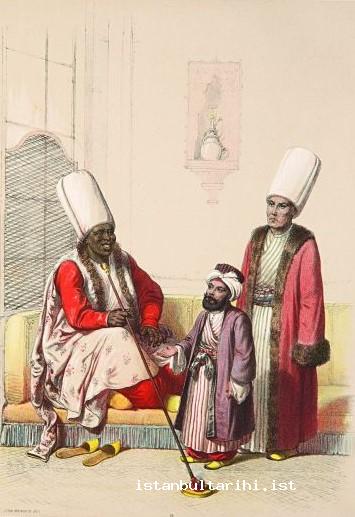

The two-story structure contained approximately 140 wooden mannequins inside display cases, all of which were dressed in the attire of statesmen and civil servants from the past. The book Elbice-i Atika: Musée des Anciens Costumes Turcs de Constantinople, published in 1855, presents a comprehensive record of the costumes and displays at this exhibition (Photo 5).10

However, the Ancient Clothing (Elbise-i Atika) Museum was to move from this location shortly afterwards. It was moved first to the School of Industry (Mekteb-i Sanâyi) in Sultanahmet and remained there for many years. It was then moved to a few different locations during the reign of Sultan Abdulhamid II (1876-1909), before being relocated in one of the halls of the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Mining (Ziraat, Orman ve Maden Nezareti) in the Hippodrome. Following the declaration of the Constitutional Monarchy (Meşrutiyet), the museum moved back to its original location at the Military Museum (Askerî Müze) at Aya İrini.11

Müze-i Hümayun (Imperial Museum)

In 1869, it was decided that an Imperial Museum (Müze-i Hümayun) should be established. Edward Goold, one of the teachers at the Imperial School (Mekteb-i Sultani), was appointed as curator. Goold was not an archaeologist. It is known that he was of Irish descent, had served as an officer in the Austrian army, and been in Istanbul since 1856.12 However, despite his being an amateur, during Goold’s tenure there was a noticeable increase in the collection of artifacts as compared to the past, and the collection began to quickly expand. Goold himself led an excavation in Kyzikos on the Kapıdağı Peninsula (modern Aydıncık) and returned with artifacts. Furthermore, an inventory and independent catalogue of the museum was produced, and paintings by Limonciyan, a member of staff at the museum, were added to the catalogue, which was published in 1871.13 The efforts of Goold, Grand Vizier Mehmed Emin Ali Pasha (d. 1871), and Minister of Education Safvet Pasha (d. 1883) all had a great deal to do with the developments that took place. In addition to the decision to establish a museum, the permission for an archaeological dig, the conditions for drafting a nizamname (regulation) for moving the artifacts abroad, and the publishing of a circular requesting for artifacts in the provinces to be sent to the museum all indicate that there was involvement in the project on a state-wide level.

However, these initiatives came to a halt in 1871 when Mahmut Nedim Pasha (d. 1883) came to office as grand vizier. Citing austerity measures, the pasha abolished the post of curator and appointed the artist Terenzio, on the recommendation of Austrian ambassador Prokesch-Osten, to maintain the collection.14 Shortly after this time, the museum’s activities came to a complete halt when Midhat Pasha (d. 1884) became the grand vizier and Ahmed Vefik Pasha (d. 1891) was appointed minister of education. Philipp Anton Dethier, who was appointed as director of the museum in 1872, was not an archaeologist;15 however, he was known for his works on the city’s Byzantine past and epigraphy16 prior to his appointed to this new post. Even though the nizamname that was issued during Dethier’s tenure was criticized for facilitating the transportation of artifacts abroad, it served the function of defining ancient artifacts and included rulings pertaining to their preservation from damage. Gathering artifacts remained a top priority.17 Together with a group of statues from Cyprus, during this time the museum’s collection increased from 160 to 650 pieces.

It goes without saying that the expansion of the collection created a problem in terms of space. As such, the decision to move the collection to the Çinili Pavilion from the humid and cramped Aya İrini was taken shortly afterwards, in 1873.18 The opening of this new venue took place in 1880, after the completion of renovations to the facility (Picture 6).19

In line with these developments, a decision was made to form a commission which would oversee the relocation, placement, and sorting activities at the museum.20 The finishing touch was an initiative to form a school called the Âsâr-ı Atîka Mektebi, in which museum staff would be trained. It was decided that students who knew French, Latin, and Ancient Greek would be given lessons in archaeology, numismatics, and moulage, as well as art and photography classes so that they could oversee excavations and research; the graduates would then be appointed to various provinces as superintendents. However, this proposed school never opened.21

While Dethier’s role in the institutionalization of the museum should not be underestimated, his advanced age prevented him from remaining in the post for very long. Following Dethier’s death in 1881, Osman Hamdi Bey was appointed as museum director on September 4, 1881.

It is not known how Osman Hamdi Bey was chosen as Dethier’s replacement. He was a nineteenth-century intellectual who had been educated in the West, and thus naturally had knowledge of antiquities; however, he had no prior experience in the field of archaeology. Despite this, as director he deftly managed the authority of his position together with his own personal background and social status to turn the museum into an institution of international repute in a very short period of time.

Immediately after being assigned to the post, Osman Hamdi Bey invited Salomon Reinach to carry out a comprehensive inventory and prepare a catalogue of the museum’s collection. This period of preparation, in which Hamdi Bey took part, was also a preparatory phase for activities in the field of archaeology. Following this, Hamdi Bey published a book in which he documented the tomb of King Antiochus, which had been discovered by the Germans at Mount Nemrut (Nemrut Dağı) a short time before.22 This was followed by the Sayda excavation of 1887. The excavation and the discoveries made there caused a great deal of interest in the European archaeological community. A comprehensive and high quality publication, prepared with the help of archaeologists such as Theodor Reinach and Ernest Chantre, played a role in this becoming a prestigious site.23

Meanwhile, the Ottoman State published the third set of regulations pertaining to antiquities (Âsâr-ı Atîka Nizâmnâmesi), prepared by Osman Hamdi Bey. This set of regulations would differ from others in that it considered every artifact found on Ottoman soil as belonging to the Ottoman State, and to a great extent prevented the artifacts from being transported abroad. This led to serious international opposition. However, there is no doubt that it strengthened the position of the Ottoman State and the status of the museum.

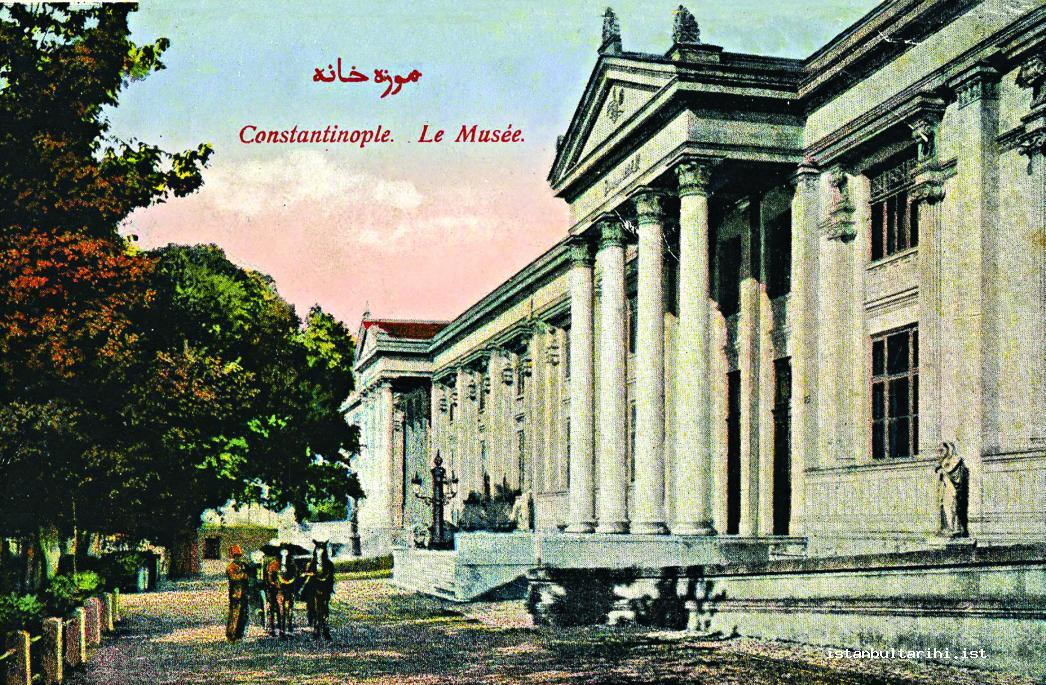

Osman Hamdi Bey used this state of affairs to improve the physical condition of the museum. Particularly following the Sayda excavation, it became evident that the Çinili Pavilion lacked the necessary space to display all of the museum’s artifacts. In 1887 the plan for a new building for the museum, designed by Alexandre Vallaury, was approved. The venue opened its doors to the public in 1891, after the construction had been completed. The museum quickly expanded under the new plan, adding several new structures to the main building in only a few short years. Within one year, an additional structure featuring a photography studio, a modeling studio, and library were added by Pietro Bello.24 These were overseen by Vallaury, and opened in 1903. In 1904, another addition, also overseen by Vallaury, was completed by the son of Osman Hamdi Bey, an architect by the name of Edhem Bey (Picture no. 5).

In 1904, the museum consisted not only of the collection and the building which held it, but also a studio and library that allowed for work to be carried out on the collection. Additionally, the School of Fine Arts (Sanayi-i Nefise Mektebi) which had operated in the courtyard of the museum since 1883, was formally connected, both physically and administratively, to the museum.25 This reflects the mindset of the era, in which art and architectural education were closely related to archaeology and museums; moreover, this focus on education indicates the lack of and need for trained specialists in the field at the time.

Following Osman Hamdi Bey’s death in 1910 he was replaced by his brother, Halil Edhem, who had served as deputy director until that point. Mufid Mansel describes this era as the teşkilat (organization/formation) era, thus emphasizing the efforts that were made to reorganize the exhibitions there.26 It is possible that the circumstances of war and occupation prevailing at the time could have played a role in this development. Furthermore, in 1917, the removal of the School of Fine Arts from the museum courtyard and the establishment of the Ancient Oriental (Eski Şark) Collection in its place may have led to the restructuring. Between 1911 and 1918, Eckhard Unger was invited from Germany to oversee this new part of the museum. In addition to this, a three-volume catalogue of Greek, Roman, and Byzantine statues27 was another important step in the definition, classification, and promotion of artifacts in this era.

A law for the preservation of monuments (Muhâfaza-ı Âbidât Nizamnâmesi) was published in 1912.28 In the same vein, the Committee for the Protection of Monuments (Muhâfaza-i Âbidât Encümen) was established in 1917. The committee consisted of the chairman, Halil Edem Bey, as well as other individuals he suggested. It served as an institution that maintained organic ties with the museum until the early years of the Republic.

In the Republican Era the Imperial Museum, and the Çinili Pavilion and Ancient Oriental Museum which were affiliated with it during the period, was renamed the Istanbul Archaeological Museum (İstanbul Arkeoloji Müzesi), though it retained its existing location.

The directorship of Halil Edhem coincided with a time in which nationalist sentiments were becoming more and more pronounced, inching away from a nineteenth-century cosmopolitanism towards the increasing prominence of Turkish and Islamic influences. Halil Edhem’s works on Islamic seals, sikke (coins), and inscriptions, coupled with the fact that the establishment of the Pious Foundations (Evkaf) Museum took place during this era, are helpful hints in understanding the backdrop of the time.

Evkaf-ı İslamiye Müzesi (Museum of Islamic Pious Foundations)

The Regulation Concerning the Imperial Museum (Müze-i Hümayun Nizamnâmesi),29 which was approved by the Council of State (Şura-yı Devlet) in 1889, divided the Imperial Museum collection into six sections: 1) Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Artifacts; 2) Assyrian, Chaldean, Egyptian, Phoenician, Hittite, Arab, and Other Asian and African Artifacts; 3) Islamic Artwork; 4) Numismatics; 5) Natural History; and 6) the Library of History and Archaeology. The size and importance of these sections, described in the regulations without any hierarchical reference, are not the same as those in 1899. The Near East and Islamic works collections grew over time and eventually became separate museums. The Natural History Museum (Tabiat Tarihi Müzesi), in marked contrast to museum development in Europe at the time, would never develop as part of the Imperial Museum. As a trial, it was placed within the School of Medicine (Mekteb-i Tibbiye) following the Young Turk revolution.30

The growth of the collection of Islamic artwork was to a great extent a reaction to developments in Europe at the time. In nineteenth-century Europe, the notion of Islamic arts had gained increasing prominence in the art world. As a result, there was an increase in the theft of artifacts kept in mosques, tombs, and libraries. In tandem with these developments, an increased awareness of the need to preserve artifacts in museums emerged. An amendment made to the regulations for the preservation of antiquities in 1906 stated that any artifacts known to exist or yet to be discovered within the empire were under the ownership of the Ottoman State; this ruling was expanded to include Islamic artifacts.31 In September 1908, the Ministry of Pious Foundations (Evkaf Nezareti) summoned Osman Hamdi Bey to a meeting32 to discuss possible measures to protect artifacts found in mosques and tombs, measures to be paid for out of the ministry’s budget. The ministry planned to construct a new museum to house these artifacts, and requested that they be moved to the Çinili Pavilion for their protection until the new museum was completed. The removal of the Islamic works collection from the upper floor of the new building of the Imperial Museum to the Çinili Pavilion was most likely the result of this communication.

In 1910 it was decided that a commission be formed at the museum in order to develop proposals for the preservation of Ottoman and Islamic artwork and a plan for their implementation.33 The commission was charged with discussing the merits of possible measures for preventing artifacts from disappearing, such as photographing and cataloguing artwork housed at religious and other sites. The commission was also to implement whatever such measures it ultimately decided upon. The decision, signed by Minister Emrullah Bey, also suggested that a decision to publish an illustrated book that covered the history and artistic value of such architectural sites and artifacts was under consideration. However, it is unknown whether efforts were made to bring this project to life.

During the time Hayri Bey was the Minister of Pious Foundations, an administrative committee was formed in order to oversee efforts to establish a new museum. Friedrich Sarre took part in the commission’s preparations for the arrangement and exhibition of the collection.34

The imarathane (hospice) in the Süleymaniye complex was allocated as a location, and the museum was opened in 1914. Rugs and manuscripts formed an important part of the items displayed in this building. In an article35 which featured the Pious Foundations Museum, written in 1918, it is noted that the display consisted of four galleries: the largest contained the manuscripts, while another contained textiles, and the other two included wooden objects and evaniye (pots and pans). The rugs were displayed on the walls of the various galleries. When the museum opened in 1914, it also contained a school offering classes in such arts as calligraphy, miniature, mucelletlik (book binding), and tezhip (illumination).36

With the abolishment of the Ministry of Pious Foundations in 1924, this museum was placed under the control of the Ministry of Education and the Public Directorate of Istanbul Museums (İstanbul Müzeleri Umum Müdürlüğü). The name was changed to the Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum (Türk ve İslam Eserleri Müzesi). With the closing of the tekkes and zaviyes (dervish lodges) and tombs, many more artifacts were added to the museum’s collection. In 1983, the Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum left its home at the Süleymaniye İmarathane and moved to the İbrahim Paşa Palace located in the Sultanahmet district of Istanbul.

Askeri Müze (Military Museum)

Aya İrini ceased to function as a museum during the era of Sultan Abdülmecid, and was transformed into a military storehouse after the Ottoman-Russian War of 1877-1878. The weapons that were stored there during the reign of Abdulhamid II were no longer open to the general public, with the exception of certain people with special permits.

At the same time, however, this closure coincided with initiatives to open a new military museum. Ahmet Muhtar Pasha had presented Zeki Pasha, the Marshall of the Imperial Arsenal of Ordnance and Artillery (Tophane-i Amire), with a proposal to this end, and Sultan Abdulhamid II had ordered that a commission be established to conduct the necessary investigations and preparatory work. This commission was made up of Ahmed Muhtar Pasha, the German artilleryman Gromikov Pasha, and the architect Jasmund. Following its investigations, the commission presented the sultan with “depictions and plans and some books and atlases.” Following this preparatory work, the details of which are not well-known, the sultan ordered the building of a model museum in one of the mansions of the Yıldız Pavilion,37 rather than building a new museum. A new commission, including the painter Fausto Zonaro, Zekai Pasha, Ali Riza Bey, as well as some military officers, was established for the construction of the model museum. The commission was headed by Mahmud Şevket Pasha.38 The commission toured Topkapı Palace and its treasury, the old weapon storehouse, the Tophane and Maçka arsenals, and the Tersane arsenal, organizing the transfer of goods which they considered suitable for the museum, keeping a record of the goods collected, and creating a catalogue39 which included watercolor paintings. However, the museum was closed shortly after this, and the items displayed were sent to the Maçka arsenal.40

While the model museum was being set up, a competition was held for the design of a new museum. A five-person architectural group, known to have included Raimondo D’Aronco and Vedad Bey, was invited to take part.41 Vedad (Tek) Bey was awarded first place in the competition; however, no steps were taken to realize his vision.

Following the declaration of the Constitutional Monarchy, a commission was formed on the order of Sultan Abdulhamid II and at the recommendation of Rıza Pasha, the Marshall of the Imperial Arsenal of Ordnance and Artillery. The commission was headed by Ahmed Muhtar Pasha. Because a suitable building could not be found, however, the process ground to a halt yet again.

The first successful initiative to secure a location for the Military Museum took place under Mahmud Şevket Pasha’s tenure at the Ministry of War (Harbiye Nazırlığı). It was decided that instead of creating a new building for the museum, Aya İrini should be used. Once this idea was accepted, Ahmed Muhtar Pasha was assigned as the new director of what was to be called the Military Weapons (Esliha-i Askeriye) Museum. Attempts were made to move the contents of the model museum in Yıldız Palace to the Military Museum, as well as the weapons granted to the treasury after the dethronement of Abdulhamid II. Furthermore, weapons and armor from houses and tombs around the city of Bursa were collected and items that reflected the glory of the early era of the empire were selected by a military commission.42 The museum was opened to the public in 1910 (Photo 2).

The new Military Museum differed from previous museums in that it based its efforts around a “target audience” of prospective visitors, thus aligning itself more closely with modern curatorship techniques. Special care was taken to ensure that items on display had explanatory tags, thereby catering to individuals who had no knowledge of history.43 In 1916, the janissary mannequins were brought from the Hippodrome to Aya İrini in order to add to the visual appeal of the museum (Photo 3). An archive and library were also established in the museum.44

The Military Museum remained at Aya İrini during the Republican Era as well. Items on display were moved to the city of Niğde during World War II, to protect them from being damaged. The Maçka arsenal was allocated as the location for the museum when it relocated to Istanbul in 1949. However, this building was given to Istanbul Technical University (İTÜ) before the museum had been moved; it was then transferred to the gymnasium of the Military School (Harbiye Mektebi). The move to this location was completed in 1959, after which point the museum opened to the public. The gymnasium eventually proved inadequate, and the museum was relocated to the main building of the school itself.

Bahriye Müzesi (Naval Museum)

Around the same time as Fethi Ahmed Pasha was occupied with converting Aya İrini into a museum, a move was afoot to establish a naval museum at the Imperial Shipyard (Tersane-i Amire) in Kasımpaşa. During Hüsnü Pasha’s time as Minister of the Navy, a commission including Süleyman Nutki and Captain Hakan was established under the leadership of Miralay Hikmet Bey. Following efforts by the commission, old weapons, objects, maps, etc., from the various sections of the Imperial Shipyard were gathered. On August 31, 1897, the museum opened to visitors.

During the Constitutional Monarchy period, the appointment of the artist Ali Sami (Boyar) Bey as director of the museum led to a number of new efforts, including the preparation of a catalogue.45 Despite these efforts the museum remained, in the words of Ali Sami Bey, “a carefully organized museum depot,”46 as opposed to an actual museum. The imperial yachts, which formed a good portion of the collection, were located in the boathouses of various palaces. In 1913, the yachts at the Yalı Pavilion of Topkapı Palace were moved to the docks at the Imperial Shipyard. It was not until the Republican Era that they would all be brought together. In 1918, an initiative was contemplated that would have tied the two castles of Anadoluhisarı and Rumelihisarı, which stand opposite each other on either side of the narrowest point of the Bosphorus, to the Naval Museum.47 A series of expropriations48 and renovations took place at Rumelihisarı, led by the Swedish architect Maximilian Züchrer, who was in Istanbul at the time serving as the Public Director for Construction and Industry.49 However, the war and eventual occupation of Istanbul prevented the project from being completed. The museum was moved to the Nakkaşhane (Atelier) of the shipyard in 1933. During WWII, the collection was moved to Konya, as with many other collections, in order to protect it from the threat of impending war. The collection was brought back to Istanbul in 1946 and stored in a depot at the Divanhane (Reception Hall) of the shipyard. When the museum was reopened in 1948 it was housed in Dolmabahçe Mosque and the palace garage. When the Beşiktaş Tax Office was allocated for use by the museum, a long-term solution to the problems of space and venue were solved. The museum functions today as the Naval Museum (Deniz Müzesi) in its new building.

All the efforts described here demonstrate a strong determination to create a museum culture on the part of the Ottoman State. It is important to note, however, that these efforts did not coincide in the Ottoman Empire, as they often did in Europe, with the formation of a universalist historical discourse or with efforts to lay the foundation for a policy of imperial expansion. Although the Ottoman State was at this time at a crossroads, and was heading towards becoming a nation-state, it did not yet envision museums as a means of offering its citizens an idealized portrait or official narrative of the state or its history. During this era, museums were a vehicle for a struggle against a certain cultural discourse which was perceived as a threat to the existence of the state. The Ottoman Empire was able to do this in a way similar to Western countries: by shaping the historical narrative in a way that was in keeping with its own discourse. The fact that Istanbul was home to an intellectual population which was cosmopolitan and could form and maintain this discourse and share it with the masses played a role in the establishment and growth of museums in this city. Istanbul’s exceptional status in this regard is underlined by the fact that until the 1920s, only a very few cities in Anatolia like Bursa and Konya had their own museums.

However, very little is known about the place of museums in urban life in the Ottoman period. Speaking of an exhibition at Aya İrini, Shaw writes that “much of its power relied on its general inaccessibility.”50 Even if intellectual circles were aware of the exhibition’s existence, the fact that visits were restricted to sultans and select foreigners meant that its contribution to urban life at the time was more symbolic than actual.

In 1869, following the establishment of the Imperial Museum and while debates were taking place about moving the archaeological collection to the Çinili Pavilion,51 criticisms of the inaccessibility of Aya İrini to the general public and subsequent changes made by the museum can be seen as signs that this institution was intended to cater to a larger audience. In a city-guide by J. Murray,52 dated 1871, it is noted that the gardens of the museum could be entered without special permission. Additionally, the guide discusses the entrance fee to the museum. Both details point to a broader public for the museum than merely a select few.53

However, just how widely and by whom the museum was visited remains unknown. The Sublime Porte bureaucrats, who constituted a large percentage of the city’s intellectuals, can be said to have formed a substantial portion of local visitors to the museum. The School of Fine Arts is believed to have visited the museum for various reasons, but although official records note that the museum was meant to have an educational function, there is no concrete information on who the target of this educational mission was or how it was implemented. Shaw’s view, that the museum’s priority was expanding its collection rather than catering to visitors, is meaningful in this regard.

There is no doubt that museums were seen as an important vehicle for the developing nationalistic discourse of the period. However, it is also important to note that the nationalism of the period was more of a proto-nationalism, a means discussed by the nineteenth-century Ottoman elite for the purposes of preserving the state, rather than a nationalism of the modern variety. In this regard, it can be said that Osman Hamdi Bey’s museum viewed the local/foreign administrators and cultural elite as its target audience, rather than the general masses of the city. The antique weapons in Aya İrini and the Imperial Museum are among the must-see locations listed in nineteenth-century city-guides prepared for travelers. Such travelers were assumed to have knowledge about Eastern art, archaeology, and similar topics. In the earlier nineteenth-century guides, the Imperial Museum was listed in a general fashion in the section on palaces. Towards the end of the century these guides began to offer more expansive coverage of the various items showcased in the individual rooms of the museum, thus revealing a growing interest in it as a site to visit on the part of foreign travelers to the city.

In the late Ottoman Era, and especially after the Young Turk revolution, nationalism took on a more popular aspect in line with the growing need to reach, mobilize, and secure the support of the public at large. In line with this, Istanbul’s museums began to be refashioned in order to cater to normal residents of the city. The regulations for the Pious Foundations Museum set out a set of rules for students visiting from the city’s various schools, who were expected to be accompanied by their teachers.54 However, the most notable change took place at the Military Museum, which tried to publicize itself through the local press. The opening of the museum was announced with advertisements and articles in the papers.55 People were asked to donate military items that had been passed down in their families to the museum, and those who did so were photographed for the press.56 Such practices as live models wearing Janissary attire touring the facilities and a Janissary band giving live performances in the museum must have been attempts to allow visitors who did not have much knowledge or understanding of the past to gain insight into Ottoman history. Furthermore, the screening of movies that were not always military in nature is interesting in terms of understanding the museum’s efforts to attract members of the public to the museum.

Just as museums’ place in the public life of the city was rather limited, so too was their representation of the city’s past. The artifacts which formed the bulk of the collection at Aya İrini were inherited from the Byzantine Empire. One would think, given the depth of the city’s history, that many artifacts would have turned up during the course of construction activities in the city and been handed over to the museum.57 However, the number of artifacts from Istanbul included in the catalogues is negligible. The fact that urban development was ongoing in regions which had been residential areas in ancient Byzantine no doubt created problems for archaeological work in the city. In fact, archaeological excavations in the city during the Ottoman Era only became possible after a fire broke out in İshakpaşa in 1912, leaving the district open for archaeological excavation.58 The excavations at the palace there, which had been known as the Great Palace (Büyük Saray), were carried out by Mamboury and Wiegand. In contrast to museums in European countries, which Shaw describes as bringing artifacts from across the lands that they had colonized together in their capital cities and thus emphasizing their imperial power, the Imperial Museum developed a language based on archaeological property and used this to underscore Ottoman sovereignty over its territory.59

As such, it is not implausible to suggest that the priority of the museum was not Istanbul archaeology. The first excavation organized by the Imperial Museum in Istanbul took place at Gülhane Park, after the park had been created, and was led by Eckhardt Unger, who had been invited to the Ancient Oriental Artifacts section in 1913.60 The second excavation was carried out in Bakırköy in 1914, led by Theodor Makridi from the museum.61 Interrupted during the war, the excavation was taken over by the French occupying forces under the leadership of M.C. Picard.62 Another excavation, which was also carried out by the French occupying forces, took place in the Mangan section of the palace under the leadership of R. Demangel, but in cooperation with the museum.63

During the Ottoman Era, the Imperial Museum played an important role both in terms of the collection and exhibition of historical artifacts and also in terms of the development and implementation of policies for their protection throughout Ottoman territory. The latter idea, which initially centered on archeology, expanded to include both Islamic and Ottoman artifacts at the beginning of the twentieth century, including the historical monuments of the city. The museum’s Committee for the Preservation of Monuments (Muhafaza-i Âsâr-ı Atîka Encümeni) represented the vehicle by which it was most directly involved with the city of Istanbul. The committee was formed in 191764 in order to protect the historical and architectural structures of Istanbul from damage, whether through negligence or willful harm. The committee was tasked with identifying and documenting important structures by means of photographs and sketches. An examination of an activity report from 1920 reveals that what the committee envisaged was the collection of a dossier for each such site, replete with a map showing its location, architectural sketches, copies of any inscriptions at the site, as well as general information about and descriptions of the location.65 The committee continued to function in the early years of the Republic, and its work was used in the development of laws pertaining to the protection of historically significant buildings in the Republican period.

There is no doubt that the museums in Ottoman Istanbul constituted an important model for their successors in many ways. Many carried on their operations and continued to expand their collections during Republican period. In so doing, they played a vital role in carrying Istanbul into the spotlight and elevating the city to a respected position among the important cultural centers of the world.

FOOTNOTES

1 See: Aziz Ogan, Türk Müzeciliğinin 100. Yıldönümü, Istanbul: Türkiye Turing ve Oto Kulübü, 1947, p. 3; Tahsin Öz, “Ahmet Fethi Paşa ve Müzeler,” Türk Tarih, Arkeologya ve Etnografya Dergisi, vol. 5 (1948), p. 1; Remzi Oğuz Arık, Türk Müzeciliğine Bir Bakış, Ankara: Milli Eğitim Bakanlığı, 1953, p. 1; Kamil Su, Osman Hamdi Bey’e Kadar Türk Müzesi, Istanbul: Fono Matbaası, 1965, p. 7; Mustafa Cezar, Sanatta Batı’ya Açılış ve Osman Hamdi, Istanbul: Erol Kerim Aksoy Vakfı, 1995, vol. 1, p. 228.

2 Moniteur Universel, Mar. 20, 1846 and Dec. 2, 1847. Cited in Edhem Eldem, “Müze-i Hümayun,” Osman Hamdi Bey Sözlüğü, Istanbul: Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı, 2010, p. 391.

3 For two different anecdotes on this matter, see: Sermed Muhtar, Topkapı Sarây-ı Hümâyûnu Meydânında Kâin Müze-i Askeri Züvvârına Mahsûs Rehnümâ, Istanbul: Necm-i İstikbal Matbaası, 1920, p. 28; “Osmanlı Müzesinin Sûret-i Tesîsi,” Servet-i Fünûn, 1326, no. 984, p. 347.

4 Jean-Claude Flachat, Observations sur le Commerce et sur les Arts D’une Partie de l’Europe, de l’Asie, de l’Afrique et Même des Indes Orientales, Lyon: Chez Jacquenod pere & Rusand, 1766, vol. 2, p. 165; Edward Daniel Clarke, Travels in Various Countries of Europe, Asia and Africa, London: Printed for T. Cadell and W. Davies, 1817, vol. 3, p. 11.

5 Gustave Flaubert, Voyages-II, Paris: Louis Conard, 1910, pp. 44-45, 53-54; Théophile Gautier, Constantinople, Paris: M. Lévy, 1853, pp. 287-88, 311-322.

6 Sermed Muhtar, Topkapı Saray-ı Hümayunu Meydanında, p. 28. Tahsin Öz mentions a story about this room being prepared for the sultan. Öz, “Ahmet Fethi Paşa,” p. 7.

7 For more information about Albert Dumont, see: Edhem Eldem, “Dumont, Albert,” Osman Hamdi Bey Sözlüğü, pp. 180-181; Eve Gran-Aymerich, “Dumont, Albert,” Les Chercheurs du Passé, Paris: CNRS éditions, 2007, pp. 763-765.

8 Albert Dumont, “Le Musée St. Irène à Constantinople,” Revue Archéologique, no. 18 (1868), pp. 237-263.

9 For information on the new location of the structure, see: Gautier, Constantinople, p. 311.

10 Jean Brindesi, Elbice-i Atika: Musée des Anciens Costumes Turcs à Constantinople, Paris Lemercier, 1855.

11 Wendy Shaw notes 1868 as the date on which the mannequins were returned to Aya İrini. However, Sermed Muhtar’s opinion should also be taken into account. Noting that Edmondo de Amicis, who travelled to Istanbul in the 1870s, described the museum as located in the district of Sultanahmet in his memoirs, Muhtar argues that the mannequins in question were not returned to Aya İrini until after the establishment of the first constitutional monarchy in 1876.

12 For information on Edward Goold, see: Semavi Eyice, “Arkeoloji Müzesi ve Kuruluşu,” TCTA, VI, 1598-1599.

13 The catalogue in question was published as Issue 1359 of Takvîm-i Vekâyi, on 28 Safer, 1288. The French edition was by Edward Goold, Catalogue Explicatif, Historique et Scientifique d’un Certain Nombre D’objets Contenus dans le Musée Impériale de Constantinople, Istanbul: A. Zellich, 1871.

14 Almost all of the sources used here describe Terenzio as an artist, while Alpay Pasinli refers to him as a person knowledgeable in numismatics, noting that thanks to the Austrian ambassador, Prokesch-Osten, he was able to examine thousands of coins in the museum. Alpay Parsinli, İstanbul Arkeoloji Müzesi, Istanbul: Akbank, 2003, p. 14.

15 It is not particularly clear what Dethier’s training was. He signed his works in the Revue Archéologique as Dr. Dethier. Edhem Eldem noted that Dethier was someone who “had not even attended university and had educated himself, in large, by satisfying his curiosity.” Wendy Shaw reports that he had been “educated in history, philology of the classical era, architecture and art history at Berlin University.” (Wendy Shaw, Osmanlı Müzeciliği: Müzeler Arkeoloji ve Tarihin Görselleştirilmesi, tr. Esin Soğancılar, Istanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 2004, p. 109; Edhem Eldem, “Dethier, Philipp Anton,” Osman Hamdi Bey Sözlüğü, p. 169).

16 For information on Dethier’s research on Istanbul’s history and epigraphic works, see: Semavi Eyice, “İstanbul Arkeoloji Müzelerinin İlk Müdürlerinden Dr. P. H. Anton Dethier Hakkında Notlar,” İstanbul Arkeoloji Müzeleri Yıllığı, 1960, no. 9, pp. 45-52; Edhem Eldem, “Dethier, Philipp Anton,” pp. 169-170.

17 It is known that Dethier contracted agents from Thessaloniki, Bandırma, and Istanbul, acquiring their help in collecting artifacts. It is known that Giovanaki from Thessaloniki, Takvor Agha from Bandırma, and Derviş Hüseyin from Istanbul were involved. For more information on this see: Gustave Mendel, Catalogue des Sculptures Grecques, Romaines et Byzantines, Istanbul: Musée impérial, 1912, p. XIX.

18 Aziz Ogan notes that, prior to Dethier, the idea of using the Çinili Pavilion was first suggested by Subhi Pasha (d. 1886) when he was minister of education (1867). (Ogan, Türk Müzeciliğinin 100. Yıldönümü, p. 7).

19 In a Maarif Meclisi (education assembly) memorandum, published by Kamil Su on May 1, 1878, there is mention of negotiations for a “map” which would transform the Çinli Pavilion into a museum. (Su, Osman Hamdi Bey’e Kadar Türk Müzesi p. 57). Eldem notes that Montereano was a Greek architect and that the renovation project was given to him (Edhem Eldem, “Çinili Köşk,” Osman Hamdi Bey Sözlüğü, p. 153; Ogan, Türk Müzeciliğinin 100. Yıldönümü, pp. 7-8).

20 See: Su, Osman Hamdi Bey’e Kadar Türk Müzesi, pp. 32-34, 60-61.

21 For more information on the initiatives for this school, see: Osman Nuri Ergin, Maarif Tarihi, Istanbul: Eser Neşriyat, 1977, vol. 1-2, pp. 709-712; Su, Osman Hamdi Bey’e Kadar Türk Müzesi, pp. 29-32, 60; Cezar, Sanatta Batı’ya Açılış, pp. 243-245.

22 O. Hamdy Bey and Osgan Effendi, Le Tumulus de Nemroud Dagh. Voyage, Description, Inscriptions Avec Plans et Photographes, Istanbul: Impr. F. Loeffler, 1883.

23 O. Hamdy Bey and Théodor Reinach, Une Nécropole Royale à Sidon, Paris: E. Leroux, 1892.

24 Pietro Bello’s name is mentioned as Philippe Bello in many sources which cite him; however, his name was mentioned here as it is in his death record.

25 Osman Hamdi Bey was both the director of the museum and the school. Alexandre Vallaury and Pietro Bello were the architects of the museum and teachers in the department of architecture. Yervant Osgan Efendi gave lessons at the sculpture department of the school, while also working as the renovation officer. He went to the excavations with Osman Hamdi Bey. Mehmed Vahid Bey gave art history lessons at the school and prepared the museum’s guidebook in 1914.

26 Arif Müfid Mansel, “Halil Edhem ve İstanbul Müzeleri,” Halil Edhem Hâtıra Kitabı, Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu, 1948, vol. 2, p. 20.

27 Mendel, Catalogue des Sculptures Grecques, p. 14.

28 Emre Madran, Tanzimat’tan Cumhuriyete Kültür Varlıklarının Korunmasına İlişkin Tutumlar ve Düzenlemeler: 1800-1950, Ankara: ODTÜ Mimarlık Fakültesi Yayınları, 2002, p. 72.

29 For the transcript of the charter in question see: Cezar, Sanatta Batı’ya Açılış, vol. 2, pp. 547-551.

30 For the efforts to establish the Natural History Museum, see: Shaw, Osmanlı Müzeciliği, pp. 310-312.

31 For the text of the charter, see: Feridun Akozan, Türkiye’de Tarihi Anıtları Koruma Teşkilatı ve Kanunlar, Istanbul: Devlet Güzel Sanatlar Akademisi, 1977, 28-32.

32 For the document that is mentioned as being in the museum archives, see: Zarif Orgun and Serap Aykoç, “La Fondation du Musée Turc et le Musée des Arts Turcs et Islamiques,” Travaux et Recherches en Turquie, Leuven/Belgique: Editions Peeters, 1984, vol. 2, pp. 136-137.

33 Orgun and Aykoç, “La Fondation du Musée,” p. 140.

34 On this topic see: Friedrich Sarre, “Das Ewkaf Museum in Konstantinople,” Der Neue Orient, 1920, no. 8, pp. 37-38; Friedrich Sarre, “Ein Neues Museum Muhammedanischer Kunst in Konstantinopel,” Kunstchronik, 1913, no. 25, pp. 522-526; Nazan Ölçer, Türk ve İslam Eserleri Müzesi, Istanbul: 1988, p. 15.

35 Ahmed Süreyya, “Evkaf-ı İslamiye Müzesi,” İslâm Mecmuası, 1334, no. 56, 1112-1115.

36 Ogan, Türk Müzeciliğinin 100. Yıldönümü, p. 20.

37 Different authors have different views on where the model museum was opened. Both İbrahim Hakkı Konyalı and Wendy Shaw, without citing any sources, state that the model museum was located on the second floor of the Acem Pavilion (İ. Hakkı Konyalı, Türk Askeri Müzesi, Istanbul: Ülkü Matbaası, 1964, p. 17; Shaw, Osmanlı Müzeciliği, p. 260). In his memoirs, Hüsnü Tengüz, who participated in the commission to establish the museum, notes that the Feridiye Pavilion, located close to a tile factory, was prepared for this institution (Hüsnü Tengüz, Bahriye Ressamı Hüsnü Tengüz’ün Hatıraları, Istanbul: Deniz Müzesi, 2005, p. 35). Another artist who worked on the museum’s commission, Fausto Zonaro, notes that the pavilion in question was in the foothills of Ortaköy. (Fausto Zonaro, Abdülhamid’in Hükümdarlığında Yirmi Yıl, tr. T. Alptekin and Lotto Romano, Istanbul: Yapı Kredi Yayınları, 2008, p. 258).

38 Tengüz, Bahriye Ressamı Hüsnü Tengüz’ün Hatıraları, p. 35.

39 Tengüz, Bahriye Ressamı Hüsnü Tengüz’ün Hatıraları, pp. 35-36.

40 Sadık Tekeli, “Askeri Müze ve Geçirdiği Evrimler,” II. Müzecilik Semineri (Sept. 19-23, 1994), Istanbul: Askeri Müze ve Kültür Sitesi Komutanlığı, 1995, p. 25.

41 For two of the samples which Raimondo d’Aronco prepared for this competition, see: Diana Barillari, Enzo Godoli, İstanbul 1900, tr. Aslı Ataöv, Istanbul: Yem Yayın, 1996, p. 89, 109. For one of Vedad Bey’s suggestions, see: Gül Cephanecigil, “Tüm Çalışmaları,” M. Vedad Tek: Kimliğinin İzinde Bir Mimar, ed. Afife Batur, Istanbul: Yapı Kredi Yayınları, 2003, pp. 366-367.

42 Shaw, based on document no. DH. ID, 28-1:18 in the BOA, Osmanlı Müzeciliği, 265.

43 Shaw, Osmanlı Müzeciliği, p. 265.

44 Sermed Muhtar, Topkapı Sarây-ı Hümâyûnu Meydânında, p. 39

45 Ali Sami, Bahriye Müzesi Katalogu, Istanbul: Bahriye Matbaası, 1333.

46 Ali Sami, Bahriye Müzesi Katalogu, pp. 5-6.

47 BOA, MV, 211-4; BOA, DH.UMVM, 101-28; see: “Sanayi-i Milliye Müzesi Bahriye Müzesi Tarih ve Atikiyyat Komisyonu,” Türk Yurdu, 1334, vol. 14, no. 4 (154), 4105-4106.

48 BOA, BEO, 2804-210279.

49 Albert Gabriel, Les Chateaux Turcs du Bosphore, Paris: E. de Boccard, 1943, p. 30; Cahide Tamer, Rumeli Hisarı Restorasyonu, Istanbul: Türkiye Turing ve Otomobil Kurumu, 2001, p. 6.

50 Shaw, Osmanlı Müzeciliği, p. 25.

51 Su, Osman Hamdi Bey’e Kadar Türk Müzesi, p. 41.

52 John Murray, Handbook for Travellers in Constantinople, London: J. Murray, 1871.

53 Su, Osman Hamdi Bey’e Kadar Türk Müzesi, p. 45.

54 Evkâf-ı İslâmiyye Müzesi Tâlîmâtnâmesi, Istanbul: Matbaa-i Osmaniye, 1329, p. 6.

55 Nejat Eralp, “Askeri Müze,” TCTA, VI, 1606.

56 Shaw, Osmanlı Müzeciliği, p. 272.

57 It can be understood that in particular a large number of the artifacts that were found during the construction of the Istanbul-Vienna railroad, dating from 1870-1871, were added to the museum’s collection. The two lion statues belonging to the Bucoleon Palace, which were featured in Mendel’s 1912 catalogue and noted to have been added in 1871, support this theory. However, Hülya Tezcan, relying on a document in the Topkapı Palace Archive dating back to 1875, states that “the pieces from the railway route were transferred to the palace’s warehouse for later use,” indicating that perhaps a systematic gathering of artifacts in the museum was not yet taking place. (Mendel, Catalogue des Sculptures Grecques, pp. 358, 360; Hülya Tezcan, Topkapı Sarayı Çevresinin Bizans Devri Arkeolojisi, Istanbul: Türkiye Turing ve Otomobil Kurumu, n.d., pp. 24-25).

58 Batu Bayülgen, “İstanbul’da Klasik Çağlar-Bizans Dönemi Kazı ve Araştırmalarının Tarihi,” İstanbul’da Arkeoloji-İstanbul Arkeoloji Müzeleri Arşiv Belgeleri (1970-2010), eds. Z. Kızıltan and T. Saner, Istanbul: İstanbul Bilgi Üniversitesi, 2011, p. 85. The findings of this work were published at a later date. Ernst Mamboury and Theodor Wiegand, Die Kaiserpaläste von Konstantinople, Zwischen Hippodrom und Marmara Meer, Berlin, Leipzig W. de Gruyter & Co., 1934.

59 Shaw, Osmanlı Müzeciliği, p. 108.

60 Eckhardt Unger, “Grabungen an der Seraispitze von Konstantinopel,” Archäologischer Anzeiger, 1916, no. 31, pp. 1-48; Bayülgen, “İstanbul’da Klasik Çağlar,” p. 86; Tezcan, Topkapı Sarayı Çevresinin Bizans Devri Arkeolojisi, pp. 25-26.

61 Uğur Cinoğlu, “Türk Arkeolojisinde Theodor Makridi” (MA thesis), Marmara University, 2002, pp. 31-32; Bayülgen, “İstanbul’da Klasik Çağlar,” p. 86.

62 Charles Diehl, “Les Fouilles du Corps D’Occupation Français à Constantinople,” Académie des Inscriptions et Belle-Lettres. Comptes Rendues des Séances de l’Année 1923, 1923, pp. 241-248; Tezcan, Topkapı Sarayı Çevresinin Bizans Devri Arkeolojisi, p. 26; Bayülgen, “İstanbul’da Klasik Çağlar,” p. 86.

63 The findings of this excavation were published at a later date. (Robert Demangel and Ernst Mamboury, Le Quartier des Manganes et la Première Region de Constantinople, Paris: E. de Boccard, 1939).

64 Muhâfaza-i Âsâr-ı Atîka Encümen-i Dâimîsi Bir Senelik Mesâisine Dâir Rapor, Istanbul: Muhafaza-i Âsâr-ı Atîka Encümen-i Dâimisî, 1336, p. 6.

65 Muhâfaza-i Âsâr-ı Atîka Encümen-i Dâimîsi, p. 6.