It is known that in Ottoman society two conventional criteria were used to determine the school starting age for children. These were for kids to be either four years four months and four days (4-4-4) old or five years five months and five days (5-5-5). When based on their families preferences these school-aged children were about to start attending primary school, which was over the course of history called community school, primary school, preliminary school or first school, they would be specially dressed up and on the way from home to school and vice versa, at their houses and in school gardens and yards, they would with ceremonies take their first steps towards education. The ceremony at home was called the bed’-i Besmele (the starting with the [name of God]), the one held through the course from home to school was amin alayı (the amen parade for children), and the one at school was named mekteb cemiyeti (the school union). However, among the enlightened these ceremonies were all together referred as the bed’-i Besmele ceremony, and among children and people they were more commonly called the amen parade or the school union.

It is well known that families, regardless of their economic conditions, attached great importance to these ceremonies as a means to encourage their children for education, to learn how to read and write, to witness their this first joy and courage, to have this day engraved in their memories, to offer prayers for their educational lives to turn auspicious, lucky, and successful, and to welcome congratulations.

This age-old practice was developed and shaped in Istanbul, the most important center of Ottoman civilization. It comprised of several components, as follows:

1. As it was considered important to have the child that would start school dressed up on the occasion of the ceremony to go shopping for this end.

2. Visiting the tomb of an important Islamic figure located in the neighborhood and praying there. The most important places in Istanbul for this purpose were Eyüp Sultan on the European side and the tomb of Aziz Mahmud Hüdâî on the Anatolian side.

3. As part of the first assembly of the school commencement ceremony, which is bed-i besmele, to have a ceremony at home in the area of the house reserved for men, in the yard or in the garden and in front of the door of the house.

4. After this first ceremony at home, the child leaves the house with all his/her friends and their parents, and participates in this event called amen parade by stopping by the houses of other new students on the school way and singing hymns throughout.

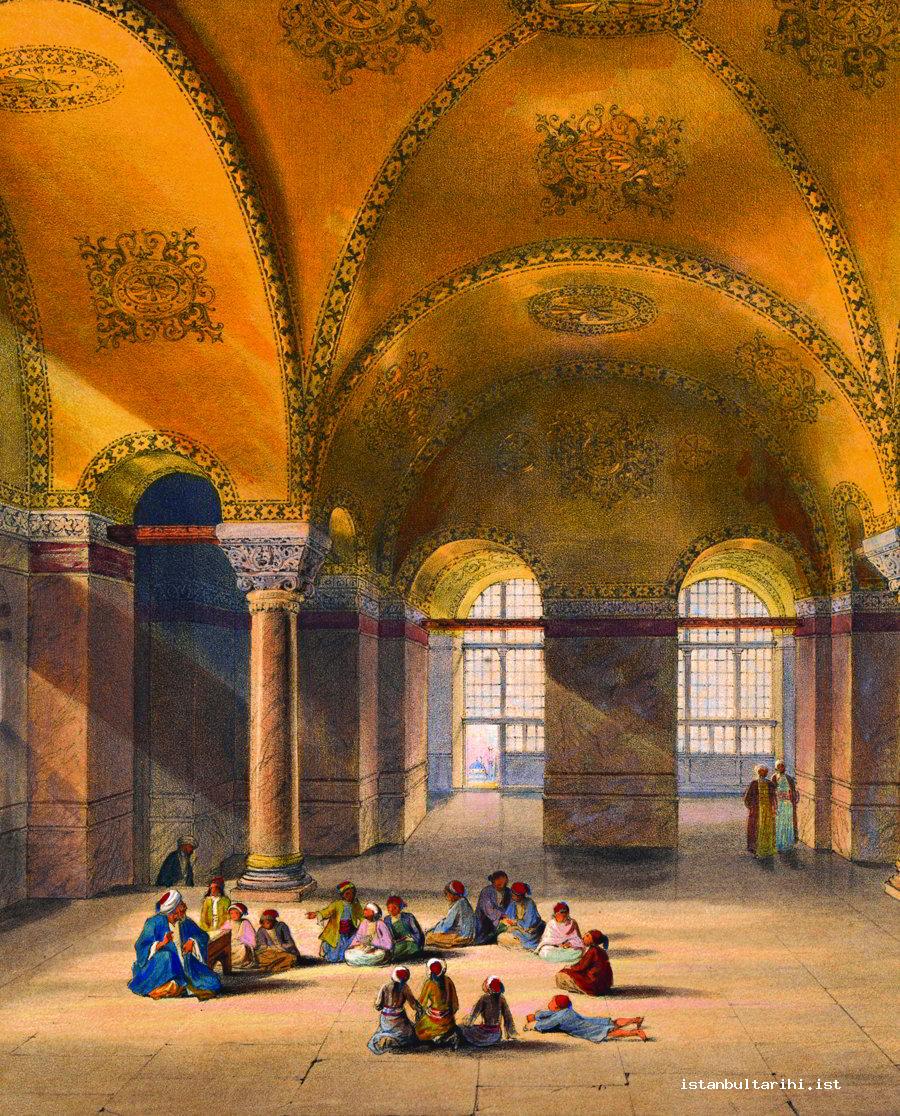

5. When the parade arrives at the primary school, holding the last ceremony, which consisted mostly of hymns and chants,.

Among the school commencement ceremonies, the last three ones mentioned above, called bed’-i besmele, the amen parade for children and the school union, were considered the most important, having the highest turnout and the greatest public outlook. While it is possible to explore each of these phases separately in great detail, the school comment practice was named after the bed-i besmele ceremony and the amen parade for children. During the ceremony school hymns, school chants and prayers constituted the foremost traditional practices. It is possible to add to this list the invitation notes to the bed-i besmele ceremony, which in the last century became part of the Ottoman style of correspondence that formed the literary prose.

The following should be paid particular attention regarding the school commencement ceremonies in Istanbul.

Invitation to the Ceremony

It was a commonly observed practice to hold the school commencement ceremonies on Mondays, Thursdays, or special religious days (kandils), which were believed to be auspicious. Acquaintances were informed about this ceremony or a note in the form of an invitation as follows would be prepared:

My son has reached the school starting age with the help and supreme favors of Allah who is superior to creation and who sent the Quran and arranged its verses. He will start learning words and complying with the intellectual act of following the right path of the master/teacher with the grace of Allah as he repeats pearls of wisdom comprised of letters and words. Therefore, please honor my house at five on this day and show the courtesy of doing a good deed in the grace and friendship of the community…

Senior members of the family, close relatives and their children, individuals from any age, gender and class in the neighborhood would attend the ceremony; as well as the school teacher (hodja), assistants (halife), janitors (bevvâb) and students who had already started the school. In addition to close relatives, depending on its social and financial standing, the family would also invite a loved and respected scholarly person, a master and sheikh, and some individuals from the military and civil service or renowned ones; thereby, having distinguished people during the ceremony for the child’s first step towards literacy.

The Celebration March: Parade / Amen Parade

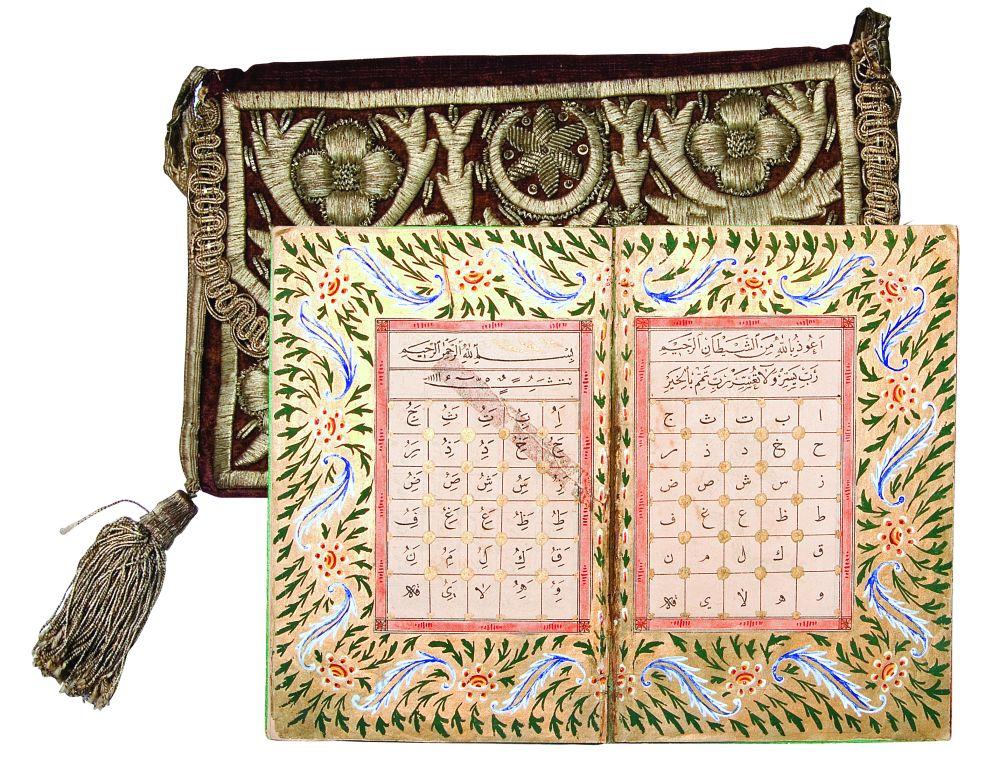

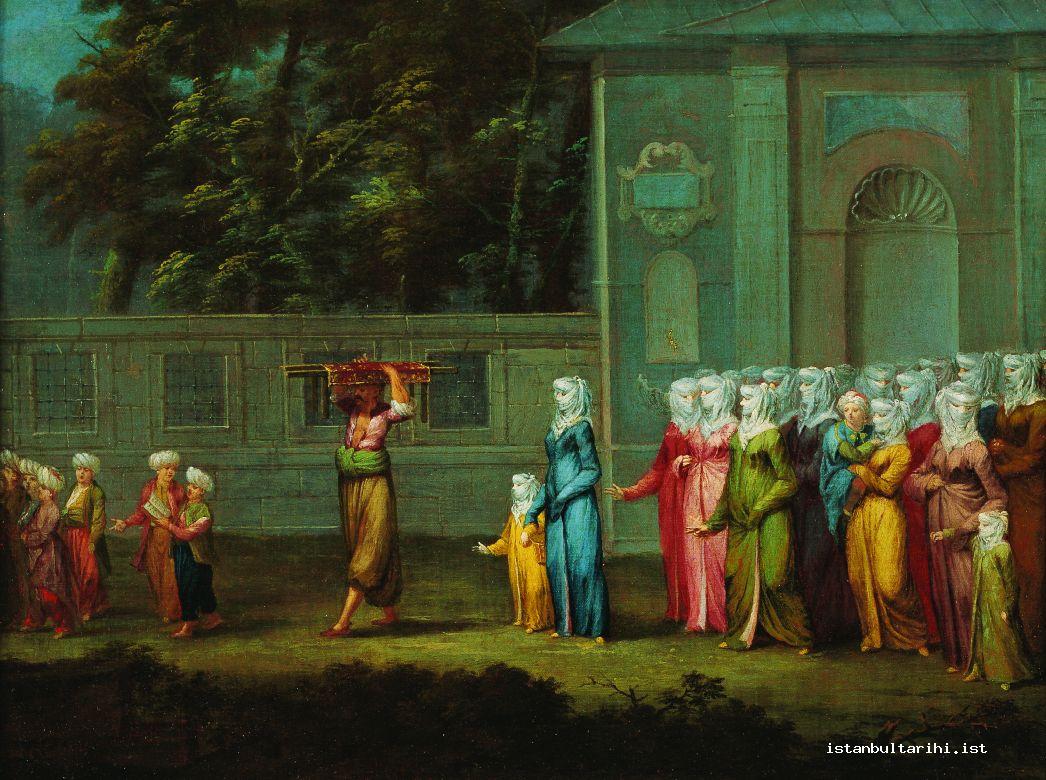

In the morning of the parade day, all students divided into two groups as chanters and amen reciters from among those that have already started school would dress up with their neatest clothes and gather at the school. One of the tallest and strongest students carrying on his head a Qur’anic codex placed on a small reading desk with precious coverlets would stand at the forefront. The group would be led by a student called ilahici başı (the head chanter) who was like a chorus or band conductor chosen from among his peers for his sonorous and beautiful voice, musical knowledge and adequate repertoire to fulfill the task of leading the chants in the best possible way. The group of students called chanters would be lined up in the front, whereas those called aminci (amen sayers), responsible for saying outloud “amen” at certain points in the chants, would form the core of the parade. In the latter boys stand in the front and girls at the back with lines composed of two or three hand-in-hand students.

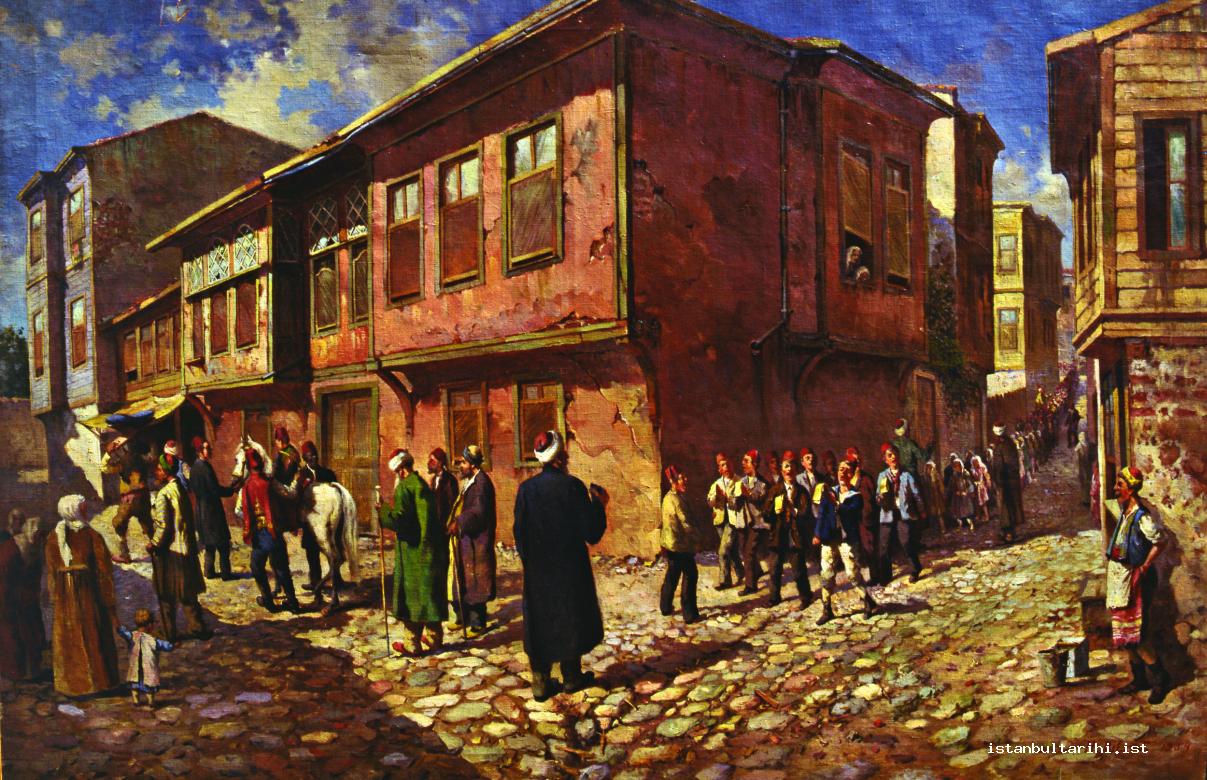

Under the supervision of the teachers and assistants to which the child would attend, the parade would leave from this school, headed towards the houses of new incoming students, singing hymns throughout the way. The head chanter walking in front of the parade would on the one hand lead the chorus and on the other the parade, when necessary walking backwards facing the students. Chanters would all together sing hymns aloud in harmony with the marching rhythm; as for amen chanters, they would say amen out loud and with great enthusiasm in between the couplets and quatrains and after the refrains. The parade would enlarge along the route with the participation of parents and residents of the neighborhood as well as people who wanted to accompany their acquaintances on their happy day in addition to acquiring merit in God’s sight by taking part in students’ first step toward leaning the Quran and attaining education, stopping in front of the house door of the child beginning school.

The Bed’-i Besmele Ceremony

If the family of the child was respected and wealthy and their house was big and available, the teacher, assistant and some of the best chanters would arrive at their house earlier along with dignitaries of the neighborhood and be seated in the area of the house reserved for men where guests were hosted. There would be a reading desk placed on a high cushion. After the hodja was seated on the cushion, the student who would be wearing elegant clothes and around his neck a small bag with a passage from the Qur’an would come to his presence through uttered supplications such as “may Allah protect him (maşallah), may Allah bless him (bârekallâh), how generous Allah is (tebârekallâh)…,” called alkış (applause). The hodja would tell the student, seated on his knees in front of the reading desk, to recite the besmele (bismillah) in front of the guests. The ceremony was named “bed’-i besmele, which means starting with the besmele or starting the besmele, since it is the first besmele the student recites under the supervision of his teacher. Subsequently, the hodja would slowly word-by-word recite the prayer “Rabbi yessir ve lâ tüassir rabbi temmim bi’l-hayr” (Oh My Lord make it easy and do not make it difficult, and oh my Lord, make it end well) and ask the child to repeat it. Following this, he would open the first page of Qur’an teaching booklet, called supara among ordinary people, or the elifba (after the first letters of the Arabic alphabet), and asks the child to repeat elifba three times, on each occasion with also demanding to utter the prayer “Rabbi zidnî ilmen” (God, increase my knowledge!). Once it was finished, those present in the room would in unison say “amen” out loud.

Following the recitation of excerpts from the Quran that prompted the reading of the Quran and acquirement of knowledge, chanters would sing some of the school hymns. After the chanter or the hodja sang the school hymn or said some prayers, this important part of the ceremony would be completed; and the hodja and the student would be given gifts; guests would be served food and dessert, and the people in the parade would be given candies and rose water would be sprinkled on them.

Affluent or wealthy families from the notables would sometimes hire for this ceremony the chanting groups of other schools or recitation choirs formed specifically by some adults to vocalize hymns at such gatherings. The ceremonies that had such groups naturally had a more shining music experience.

If the family did not have the means to hold a ceremony at home, the student would be sent to school with prayers after singing hymns in front of the house door, and their first lesson would be carried out in a similar manner in the class. In case that the child of a Sufi lodge member, especially that of a sheik and his family, started school, the part of the ceremony that would normally take place in the house would instead be performed in lodges, in accordance with the customary ceremonies of the Sufi order, in the tevhidhane or semahane of the lodge, shortly called the square.

Furthermore if there was a tekke (Sufi lodge) in the neighborhood, while the parade passed by the lodge, dervishes would join them, featuring what might be called a lodge band’s performance, singing hymns in the company of percussion instruments such as tambourine, small double drum and cymbal and also offering a greeting ceremony by rising of the flags of the Sufi order. Cemaleddin Server Revnakoğlu recounted in detail this type of tambourine performance he witnessed in Istanbul.

Amen parades organized in big cities like Istanbul were almost same in terms of their general traits. In smaller cities, the ceremonies were more modest while also having some small differences; most of the hymns were same; yet some of them were sung by using local lyrics and compositions or carrying some other differences; nonetheless, their content carried similar features. As a matter of fact, in his memoir, Yahya Kemal recorded that when they started school, children in Skopje in the parade sang the hymn “The rivers of heaven flow saying Allah Allah/ Angels of God appear and look saying Allah.”

The Return of the Parade

After this ceremony at home, the new student joined the parade on foot, and if a boy he would ride a pony and if a girl she would ride in a phaeton. With the participation of their parents, they would set out again in a convoy and go to another child’s house to perform a similar ceremony by singing hymns and saying “amen”.

After completing similar acts at the house of each student beginning school and achieving a gathering of all such children the parade as a large group would return back to the school. In the courtyard an Arabic lyric hymn, called şuğul, composed by Sheikh Mehmed Bekri, was sung in the saba melodic mode. It said “Kad fetehallahu bi’l-mevâhib ve câe bi’n-nasri ve’l-me’ârib/Ve esbeha’l-kevnü fî sürûrin ve fî emânin mine’l-metâib” (Allah provided His creatures with many blessings and brought victory; He met their needs and thus the universe was filled with happiness and protection from hardships). It was followed by the chanting of the hodja, and the ceremony ended with a prayer. Students then would go to their classes, and lessons started, while non-students in the parade dispersed.

School Hymns

While the lyrics of some of the works of music that were mentioned as school hymns in hymn periodicals and memoirs had a relatively plain and clear Turkish, a certain other were sufistic pieces composed by Sufi poets such as Yunus Emre and Niyazi-i Mısrî. Among the most renowned pieces were şuğul which were written in Arabic in a more rhythmic and vibrant mode because they were composed in quicker styles. These included a hymn with the chorus “Yessir lenâ hayre’l-umur” (oh God, facilitate our beneficial works) composed by the Sultan Mustafa II and the hymn starting with the line “Allâhu Rabbî lâ-yezâl” (God is my Lord that is always present).

Some of the best known examples are the hüzzam maqam first couplet “How lucky the person who reads the Quran” written by Yunus Emre and composed by Zekai Dede, the one he composes in uşşak maqam due to his grandchild’s beginning of school, saying “May we obey the commands of Allah and be soaked in His mercy and grace;” another one in hicaz maqam with the couplet “The rivers of heaven flow saying Allah Allah.” In the hisarbuselik maqam, “Oh Lord, we came to you, do not make us sad,” in the rast maqam “Let’s repent for our sins, I have repented to Allah,” in the acem-kürdi maqam “Oh God, let us start with bismillah” and another hüzzam one “Come and burn your body by the fire of love for the beloved of God.”

Other hymns which are known to have been sung at these ceremonies include “Thank Allah, we started on a sacred day”, “This love is an ocean, there cannot be any boundaries to it”, “Criers shout ‘ come to Allah, to the Master”, “Do you have an invocation of the name of the God /Do you have a house in the gardens”, “Oh God, please forgive us in the name of Your divine purity”, “If you want to feel relaxed look at the Quran every dawn”, “Oh God, it is us, a group of the helpless, that came to your door”.

Sheikh Saffet Efendi’s school hymns in hüzzam maqam starting with “My eyes are drenched in blood, what would I do with wine/My lungs are burned in a fire, what would I do with kebab/My body was good neither for my love nor myself, I do not know/ God, what should I do with this handful of soil” was among the works of music admired by Mehmed Akif Ersoy who was well versed in Turkish music. It was also the inspiration for Ersoy’s poem called “Amen Parade”.

Other pieces sung at school parades were “Oh veterans, the road is waiting again for this poor person” and “Ships lay in front of Sivastopol.” These were anthems loved by the public particularly after the Tanzimat era. Furthermore, during the reign of the Sultan Abdülhamid II it became customary to recite at the parades some anthems, composed in Western music style and ending with the saying “long live the Sultan!”

In the old days when there were no children songs, school hymns were used for this purpose. Their content promoted a love for the Quran, for literacy, for God and his Prophet, for religion, and acquiring knowledge and good morals. It is also worth noting that they elucidated love for homeland, recounted rewards for being martyrs and veterans for religion, state, and the nation.

The School Chant

School chants sung by an individual called “the chanter” from among the school teachers are worth studying as well. The following example, which is one of the most renowned pieces and is a prayer in Turkish, illustrates well the content of this style:

Allah Allâh, illallaah!

God is the Supreme and the Compelling, the One who hides sins, the One who creates the night and the day, the Everlasting, the Glorious, the only One. Let us say Allah with love in the name of man’s courage, the unity of God, and the veterans that became martyrs for the true religion.

Allah Allâh Allâh, always the Living (three times)

The beginning is the Quran, the end is the Quran. Blessed is the One who sent down the Quran. His hand is blood, his sword is blood, his chest is naked, his heart is longing. Let us say with love God is One in the name of veterans that became martyrs for the sake of true religion!

Allah Allah Allâh, always the Living (three times)

The beginning is war, the end is war, the help of God, the target enemy, Let us say with love God is One in the name of veterans that became martyrs for the sake of true religion!

Allah Allah Allâh, always the Living (three times)

Let us say hu, huuuu!... (Him, referring to God) for the sake of pilgrims, veterans, narrators, groups of three, seven, forty, Muhammed chanters, the divine light of Muhammed, the grace of Ali, our master Osman who had two glories of the saints...

When everybody presents responded by saying “Huuuuu!” the chanting would end.

In addition to having some local variations the chanting texts were also sometimes sung with an improvised tune, which also had local differences. Since these improvised compositions were not recorded as that practice was abolished the composition did not last to today either. Although chants were usually carried out with a big crowd at the school stage of the ceremony, they were sung in different styles and improved by texts that were customarily read in a certain lodge or Sufi order in the case of the student being the child of a lodge member.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ahmed Rasim, Falaka, Istanbul: Hamid Matbaası, 1927, pp. 51-60.

Altıntop, Mehmed Emin, “Türk Din Mûsıkîsinde Arapça Güfteli İlâhîler (Şu ğuller)” (MA thesis), Mimar Sinan Üniversitesi, 1994, p. 209.

Bayrı, M. Halit, “İstanbul’da Mektebe Başlama”, Halk Bilgisi Haberleri, 1942, no.11 (1942), p. 4954.

Beyatlı, Yahya Kemal, Çocukluğum, Gençliğim, Siyasi ve Edebi Hatıralarım, Istanbul: Yahya Kemal Enstitüsü, 1973, p. 21.

Birinci, Ali, “Mahalle Mektebine Başlama ve Mektep İlâhileri”, II Milletlerarası Türk Folklor Kongresi: Bildiriler IV, Ankara: Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı, 1982, pp. 37-57.

Birinci, Ali ve İsmail Kara, Mahalle Mektebi Hatıraları, Istanbul: Kitabevi, 1997, pp. 23-31, 40.

Ergin, Osman, Türkiye Maarif Tarihi, Istanbul: Eser Neşriyat, 1977, vol. 1, pp. 91-96.

Ersoy, Mehmed Akif, Safahât, prepared by M. Ertuğrul Düzdağ, Istanbul: Gonca Yayınları, 1987, pp. 128-129.

Musahipzâde Celal, Eski İstanbul Yaşayışı, Istanbul: Türkiye Yayınevi, 1946, pp. 29-31.

Revnakoğlu, Cemaleddin Server, “Yûnüsün Bestelenmiş İlâhîleri Nerede ve Nasıl Okunurdu?”, Türk Yurdu, Yunus Emre özel sayısı, Ocak 1996, no. 319, p. 129.

Münşe’ât-ı Azîziyye, “Bed’-i Mekteb Tezkiresi”, Istanbul: Mehmed Cemal Efendi Matbaası, 1303, p. 194.

Noyan, Bedri, Bektaşilik Alevilik Nedir, Ankara: Sanat Kitabevi, 1987, p.128.

Öcal, Mustafa, “Amin Alayı”, DİA, vol. 3, p. 63.

Pakalın, Mehmet Zeki, Osmanlı Tarih Deyimleri ve Terimleri Sözlüğü, Istanbul: Milli Eğitim Bakanlığı, 1946, vol. 1, p. 59.

Şengel, Ali Rıza, Türk Musıkîsi Klasikleri: İlâhîler, prepared by Yusuf Ömürlü, IV vol., Istanbul: Kubbealtı Neşriyat, 1979-82.

Tâhirülmevlevî, “An’anât-ı Kadîmemizden Mektebe Başlama Merâsimi”, Mahfel, 1346, vol. 4/42, pp. 114-115.

Töre, Abdülkadir, Türk Musıkîsi Klasikleri: İlâhîler, nşr. Yusuf Ömürlü, V- IX vol., Istanbul: Kubbealtı Neşriyatı, 1984-1996,

Uzun, Mustafa, “Türk Tasavvuf Edebiyatında Bir Duâ ve Niyaz Tarzı Gülbank”, İlam Araştırma Dergisi, 1996, vol. 1/1, pp. 81-82.

Uzun, Mustafa, “İlâhî”, DİA, vol. 12, pp. 66.

Ülkütaşır, M. Şakir, “Sıbyan Mektepleri ve Mektep Cemiyetleri”, Türk Yurdu, Haziran 1955, no. 245, p. 993.