The American College for Girls in Istanbul opened in 1873 as the Constantinople Home, a Protestant Christian missionary center for Bible study and domestic arts for girls and women, in Üsküdar, Istanbul. These early pupils were nearly all from the Armenian, Bulgarian, Greek, or other Orthodox (or, in missionary parlance, “Eastern”) Christian communities of Istanbul, but the missionaries anticipated that in time Muslim students would also enroll in the school. The Women’s Board of Missions in Boston, a branch of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) and the school’s founder and sponsor, envisioned a three-fold establishment that would include a high school, a medical facility, and a city mission project. In fact, only the high school came to fruition, and the educational side of the project absorbed the attention and finances of its participants and backers.

As in other American Protestant missionary projects, the school’s primary focus in its early years was Protestant evangelism; its teachers were the wives of male preachers and physicians, and its students were expected to move into similar roles after graduation. During the 1870s, however, the ABCFM yielded to pressures from its constituents and relaxed its rule against hiring unmarried women as teachers. Between 1873 and the late 1880s, Mary Mills Patrick (later to be College President, 1890-1924) and Clara Hamlin (daughter of Cyrus Hamlin, first president of Robert College of Istanbul) led the Constantinople Home in consciously transforming its image by moving its educational method from an aggressive program of religious proselytism to a more secular style of pedagogy modeled on American high schools and liberal arts colleges. At the Home School’s last commencement as a high school in 1890, its first Muslim graduate, Gülistan İsmet Hanım, daughter of an army colonel, completed her studies (receiving the equivalent of a high school degree), thus marking the school’s new identity as a secular institution. Also in 1890, with the support of the Women’s Board of Missions, the school sought and received its college charter from the State of Massachusetts, thus acquiring the authority to grant the B.A. and B.S. degrees. The trustees and faculty chose the name, “The American College for Girls,” to emphasize the school’s American affiliation and its status as an institution of higher learning; however, until the early 1930s, when an official Turkish decree banned the use of the name “Constantinople,” it was often referred to as the Constantinople Women’s College or Constantinople College. In 1901, Halide Salih (later Halide Edib Adıvar) was the first Muslim student to graduate from the College.

After the 1908 Young Turk Revolution, the College happily welcomed more Muslim students, who were now allowed legally to attend foreign schools; in the same year, the College formally ended its missionary affiliation and declared its status as private, secular, non-religious, institution of higher education, thus positioning itself to welcome a new generation of religiously diverse students. In 1905, a serious fire had prompted the College to purchase a new site in Arnavutköy, on the western side of the Bosphorus, but it was not until 1914 that the College finally moved to its new campus. The College remained open throughout the difficult times of World War I, the Allied occupation of Istanbul, and the Turkish War of Independence (1919–23), thus maintaining uninterrupted operations into the new Turkish Republic.

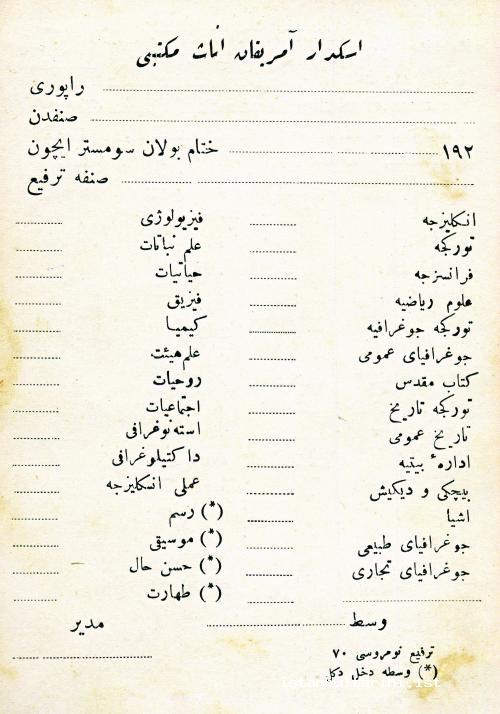

The American College for Girls actively supported Atatürk and the Turkish Republic and it expanded its operations to prepare women for new roles in education and public life. The College also adapted to other changes; for example, in 1931, the Ministry of Education decreed that Turkish citizens must be taught history, geography, and civics by Turks. In 1932, the American College for Girls and Robert College, a secular American men’s school founded in 1869, in Bebek, Istanbul, joined together as a single administrative unit with one (male) president. The two American colleges began sharing academics, faculty, arts, and social activities. From the 1930s to the 1950s, the two colleges struggled with financial shortages and readjusted their curriculum to be more in line with Turkish schools and universities. In 1957, two students from the American College for Girls enrolled in the Engineering School at Robert College and became its first women students. By 1959, the American College for Girls no longer offered a B.A. or B.S. degree; instead, it provided a middle school for day students, a four-year lise that was the equivalent of an American high school and junior college, and a language preparatory school. Robert College provided a lycée (lise) for men and a co-ed four-year undergraduate college, as well as a language preparatory academy. In the 1960s, financial problems exacerbated by anti-American protests forced an end to the continuing existence of two separate American colleges. The Ministry of Education granted permission for the two schools to merge into one coeducational lise. Robert College handed over its Bebek campus to create Boğaziçi University under Turkish sponsorship, and the two American colleges merged to become the co-educational Robert College lise on the Arnavutköy campus. In May 1971, the American College for Girls marked its Centennial celebration and the end of its existence as an independent women’s school.

Famous graduates of the American College for Girls include writer and political activist, Halide Edib Adıvar (1883-1964), and Tansu Çiller, Prime Minister of Turkey, 1993-96.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fincancı, May N. The Story of Robert College Old and New: 1863-1982, Istanbul: Redhouse, 2001.

Freely, John. A History of Robert College, the American College for Girls, and Boğaziçi University, Istanbul: Bosphorus University Press, 2000.

Patrick, Mary Mills. A Bosporus Adventure, Stanford: Stanford UP, 1934.