Research on Ottoman housing in Istanbul is a topic that cannot be constrained to local ‘Istanbul houses’ alone. There was a housing culture which was effective over a widespread region for an extended period of time; researchers refer to this phenomenon as Türk Evi (Turkish house) or Osmanlı Evi, or, in reference to a specific region, as Anadolu Evi or Balkan Evi. These houses that can be distinguished easily with their half-timbered appearance, eaves, corbels, brackets, large number of upstairs windows and typical inclusion of rooms and halls form the raw material of a poetic tradition which has remained in the societal memory. As the capital of the Ottoman State, Istanbul played an important role in the interpretation of this tradition. It may be said that this tradition may be almost as well-known and recognizable as the Classical Ottoman mosque tradition which crystallized in constructions during the sixteenth century, but has sustained its effect through later imitations. However, this tradition is much more speculative when compared for example with the aforementioned mosque tradition.

Researchers have discussed the origin and evolution of this architectural tradition, offering some different and conflicting historical narratives. The source of this uncertainty is that the Ottoman houses were made out of wood, and as a consequence, unlike the stone mosques, there is a dearth of reliable data for Ottoman houses from 250 years ago. Any scholarly explanation for the history of Istanbul’s housing, which was affected by the more general history of the city, must take into account the evolution of the Ottoman-Turkish house1 in the wider Ottoman history. Thus, taking into account the solutions produced to solve the housing shortage which occurred in Istanbul after the conquest, not only will the social structure of the era in question be examined, but the speculative history of the traditional housing issue mentioned above will be clarified.

As far as the Ottoman-Turkish housing style is concerned, Istanbul, as it is in so many other subjects, was the center. Istanbul’s central role can be evaluated within political history, but it can also be traced through its reflections in architectural history. Moreover, its political importance as a religious center increased the impact which Istanbul had on other locations in the region. Having been the center for the Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Roman churches, Constantinople continued to be a political and religious center; this situation is reflected in the architecture of Hagia Sophia. This political-religious authority, even though within a different context, would be valid once again fifty years after the conquest in Ottoman Istanbul. For the first time, the Islamic Caliphate would be passed to a dynasty that was not only outside the Quraish, but which was not Arabic and which was from a region peopled by non-Arabic citizens. During the Ottoman period, Istanbul was vested with the task of serving as the center of the Islamic universe; the construction projects of the sixteenth century which were part of this role made a substantial mark on the city’s silhouette. For instance, it is written in a treatise from 1546:

Oh those who do not pray even in Istanbul

Do not ever claim that you are of Muslim2

There can be no doubt that Latifi used hyperbole in these lines. Nevertheless, they reveal an image of Istanbul which acts as the center of Islam. It is possible to suggest that the Ottomans deliberately exported their architectural identity to the Islamic regions. Unlike the examples of the Byzantines and Hagia Sophia, the main issue here is exporting a state-planned architectural process which considered the finished product as a whole, not as symbolic of Istanbul by producing just a single Ottoman construction. This exportation project included many examples of various dimensions. Outside of Anatolia and Rumelia, domes, minarets and social complexes in the Ottoman style appeared in Egypt and Syria. İznik pottery covered the front of the Qubbat al-Sakhra. Mihrabs and minbars were made for the Masjid Nabawi, the Ka’ba was surrounded by arched and domed Ottoman porticos, and Ottoman coned minarets were constructed.

It is also true to an extent that Istanbul residences served as examples for exporting the Ottoman-Turkish housing traditions. This is clear from the features of the Hansaray, constructed by the Crimean khans in Bahçesaray, which are similar to features of Istanbul palaces (Topkapı Palace and perhaps Saray-ı Atik). Thus, it is possible to speak of an aristocratic exportation. However, this example is of little use in understanding how the housing traditions impacted the organization of the city. Moreover, it should be possible to find a chronological consistency which supports the theory of housing customs being exported. For instance, the monumental architecture mentioned above is the product of classical Ottoman architecture, and is certainly a product of the relevant century. When someone says “sixteenth-century Ottoman Houses,” does the famous Ottoman-Turkish housing style come to mind? For example, it is clear that Istanbul houses were imitated in Anatolia from the depictions of Istanbul on the walls of the main rooms, such as in Çakırağa in Birgi, Mehmed Ali Ağa in Datça, Bayramtaştepe in Manisa and the Hadımoğlu mansion in Çanakkale. However, these houses date back to the middle of the eighteenth century. Likewise, it is known in Cairo that there were houses on the Nile River which resembled the Ottoman aristocracy’s yalı (waterside houses) on the Bosphorus.3

When the overall situation is examined, it can be understood that the civilian architecture which developed during the sixteenth century, after the conquest, and the housing tradition that became known as Ottoman-Turkish housing, which, to a certain extent, was exported throughout the empire, were not one and the same thing. The houses of the sixteenth century should be evaluated as pioneers rather than as a tradition. That is, mosque architecture, which became classical in the periods after the late sixteenth century and that which is referred to as the Ottoman-Turkish housing style can be said to have still been in the formation period. There are several reasons for this. Non-civilian architecture was brought into existence with the assistance of the sultan, the dynasty and the bureaucrats, as well as with the skills of a centralized organization (hassa mimarlar ocağı) the imperial architectural guild). In contrast to housing, for the construction of this type of public structure, gaining the approval of the end-users in the provinces was not obligatory. Civilian architecture formed an overwhelming majority of the structural stock in the cities; not being subject to interference from the government, other than in relation to state construction laws, civilian architecture became a concept that was the incarnation of social realities.

For example, at all times and in all places, the types of family, wealth, life expectancy, world concepts, property and administrative systems of the society can be seen in the types of houses. When the aforementioned pioneering nature of the Ottoman-Turkish housing tradition is looked for, the conquest and afterwards - a period for which many researchers have tried to establish an idealized scheme - is one of the periods that was the peak of social movements. As this social wealth brings a plentitude which can be followed through secondary sources (vakfiye (vakfiye deeds), tahrir defter (tahrir records), qadi registers, seyahatnames, miniatures, etc.), it creates a data pool that can fill the vacuum caused by the lack of concrete examples from 250 years earlier. Synchronizing the data in this repository helps to explain the developmental phase of Istanbul housing, and thus, Ottoman-Turkish housing. Fortunately, for Ottoman-Turkish housing, Istanbul as the capital transforms the conquest into a natural beginning; such a significant and incontestable milestone is a great blessing for researchers.

To understand the development of civil architecture in Istanbul after the conquest, two main sources of data must be analyzed: the kinds of structures that were already in the city before the conquest and the techniques and styles that the newcomers brought to the city after the conquest.

Pre-Conquest Byzantine and Ottoman Houses

What kind of a civilian architecture and what kind of urban scenery did the Turks encounter when they first arrived in Constantinople? What kind of a construction base was waiting for them? Clearly, these questions can only be answered with the available information about residential architecture in the Late Byzantine period. Unfortunately, researchers do not have specific data on this topic. An overwhelming majority of the modern interest in Byzantine architecture is directed towards churches. One reason has been claimed to be that while churches were maintained up to the present day, as they were transformed into mosques and repaired, the Byzantine houses, made of wood and adobe, were all eventually destroyed by fire.4 The examples that have survived to the present day are neither useful nor artistic, thus increasing the lack of interest felt towards them.5 In fact, the basic lack of information about Byzantine housing and the partial and unavailable nature of any surviving information means that scholars are unable to create chronological or geographical theories about them; thus, the current state of evidence essentially renders the very notion of ‘Byzantine houses’ as one that can only be imagined.

The most concrete data about the houses during the Byzantine era is that from the Early Byzantine era. However, these were not in Istanbul, but rather in Syria, which underwent a lively Late Hellenistic phase, and some areas affected by the South Anatolian School. Dwellings like those in Alakilise in Lycia, Arkynda, Ksantos, and in particular, an Early Byzantine dwelling in relatively good shape in Karakabaklı in Cilicia, indicate that the residences were two-story structures of stone with wood beams. While it might be expected that the competition between the cities of the region during the Hellenistic period and that perhaps the municipal sources of Byzantine cities would be spent locally, social services in the Byzantine period were under the control of the local bishop, thus evolving into a process of church construction. This can be considered to be one of the causes for the dearth of evidence about civilian architecture in this era. When the data for Constantinople in the Early Byzantine phase are examined, according to Notitia Dignitatum, a Roman record from the fifteenth century, there were 4,388 houses (domus) in Istanbul.6 Domuses have been defined as palaces or the homes of the wealthy and while there were houses of a variety of dimensions, the insula (homes) in which the city dwellers of more modest means resided are not included in this record. However, it has been estimated that there were 2,000 insulas in the city. It has been suggested that the insulas might have been detached buildings or that the ground floors of domuses might have been used as insulas.7 In fact, it is clear that after the conquest, as after the formation of the new capital of Byzantium for Rome, there would have been a large influx of people to the city; that there were more domus than insula is an indication of a quality migration (of bureaucrats and rich Romans). At this juncture, it is possible to say that in the Early Byzantine city there was collective housing production and the social classes of the city were reflected in the texture of the city.

There is enough evidence to assert that intense construction activities took place in the city from the sixth century on; this is particularly true in the period of great progress that occurred during the reign of Justinian. For example, as mentioned above, the remnants of right-angled streets and two-storied stone houses in Arkynda present an integrity, thus suggesting that the city was a planned settlement. That there was a series of written regulations for centers like Beirut, Gaza and Ashkelon in this era indicates an empire-wide urban expansion plan and an increase in construction activities. It is known that between the fourth and seventh centuries Constantinople was no longer contained within the city walls, but overflowed, with Galata being placed in the position of a polis at this time. Again, in the fifth and sixth centuries, building laws for the city can be found. These laws demanded that every household should have a view of the sea and be able to receive daylight. From such laws it is possible to understand that the city was getting crowded and a large part of the society was settling into residential buildings. In fact, there are even records concerning that some houses had many stories and that different people were living on different floors, that is, there was an “apartment life” at this time. For example Zeno, a preacher of that period, wrote that Anthemius, one of the architects of Hagia Sophia, was his downstairs neighbor; and due to the upper floor cutting off the light to the lower apartment, Anthemius wanted to teach Zeno a lesson. Thus he boiled water in vats and sent steam to the upper floor.8

Is it possible that the insula style of housing found in the Early Byzantine period continued through the Middle Ages? The sources indicate that this tendency continued. According to the data9 that can be gleaned from travelers and chroniclers, there were wide suburban parks, cultivated areas, monasteries, summer palaces, villas, high walls and towers in the Middle Ages. It was recorded that the city was protected by marble walls, the buildings had lead roofs, there were “countless” churches, houses of three to five floors near the sea and in the town center, priests raised pigs in their apartments while the farmers stored hay. Two approaches towards city planning and material preferences became prominent in the Medieval period: houses with a courtyard, which had existed since antiquity, and a type of housing with a longitudinal architectural plan. The latter appeared more frequently towards the end of the era. From the aspect of material choice, it seems that even the poor of the city preferred a masonry system in which they used stones, bricks or adobe until the 1204 conquest by the Crusaders.10 The Latin invasion led to widespread destruction throughout the city. It is known that with the new Paleologos Byzantine dynasty, which took the city back from the Latins, a modest revival movement based on landscaping was implemented. Moreover, along with this, the era of Paleologos was the final last and weakest stage of the Byzantine period. By the fourteenth century it would have been almost impossible for the flamboyant villas with pleasant gardens outside the city, as depicted in the frescos, to have still existed.11

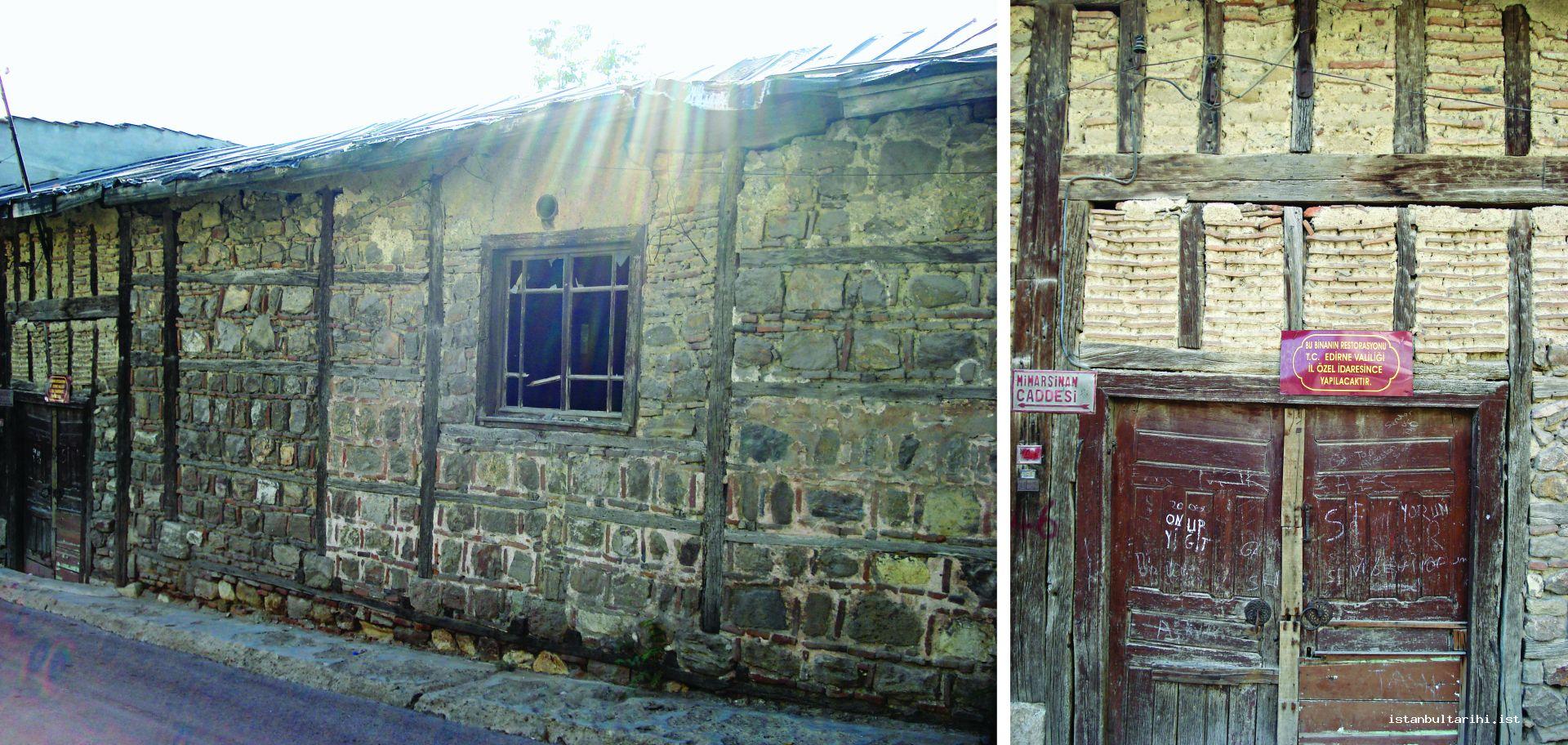

The final, weakest period for the Byzantine city, which lasted from 1261 (when the Palaeologi took back the city) to 1453, brings to mind a city that never recovered from the destruction of the Crusaders. Ambassador Clavijo, sent by Spain to Timur at the beginning of the fifteenth century, indicates that the city was large, but scarcely populated; he also mentions the planted fields and gardens in the city. Clavijo goes on to state that there were large palaces and monasteries throughout the city, but that these were in a state of ruin.12 In the fourteenth century Abu al-Fida, and in the 15th century Buondelmonti and Bertrandon de la Broquière also described the city as a place of ruin.13 There are a number of estimates about the population of the city at this time, ranging between 30,000 and 60,000. It has been suggested that in the Palaeologan period the building material for housing increasingly became wood. The construction of wooden houses is faster and more economical, in addition to this, the absence of archeological remains from the last Byzantine era supports the theory that wood was used.

The tall, narrow structures mentioned above, the use of which is thought to have increased in the late period, were probably the most common housing type that would have been encountered after the conquest by the Turks. These houses, which were known14 as Mistra,15 were distinguished by gabled roofs decorated with pediments. It is that these “long houses” started to be used in the middle Byzantine period and were a special example of housing that was shaped under the influence of the Crusaders. In the final Byzantine period the Mistra type of housing spread to the entire Greek peninsula.16

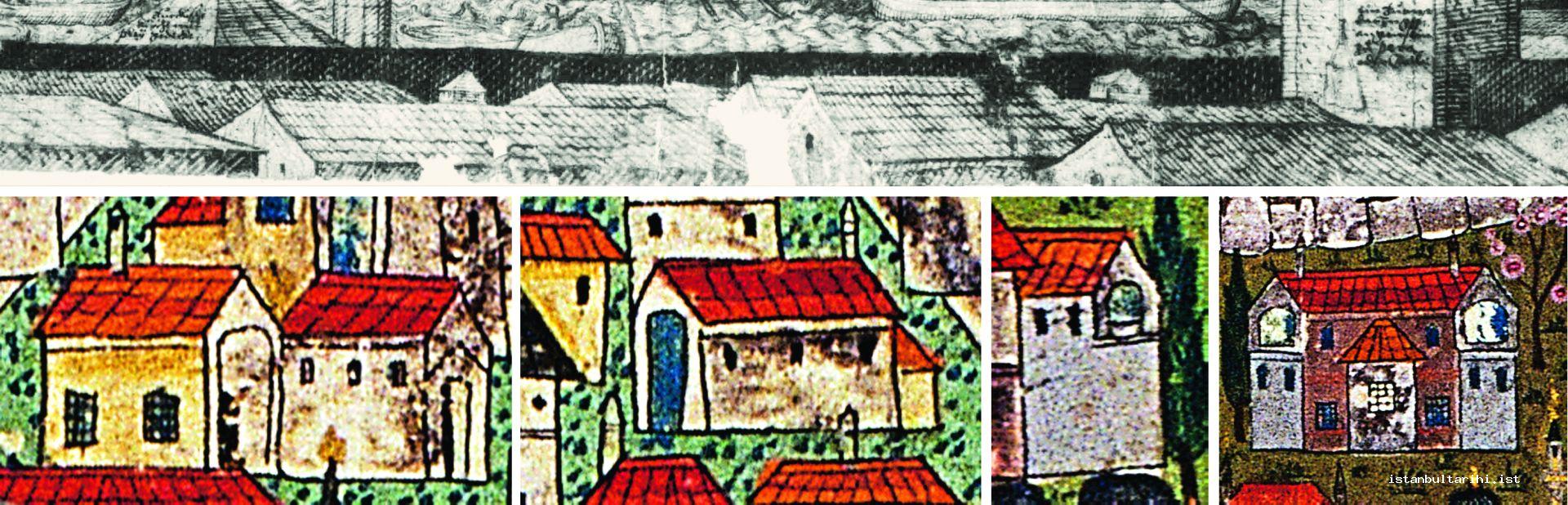

The Byzantine ruins, which are mentioned as structures or parts of structures and called kafiri in Ottoman vakfiye and deed records, and which will be discussed below, must refer to the masonry parts of the Mistra-type houses and other buildings that remained as part of the courtyard tradition. This was due to a number of reasons; for example, when Constantinople was under siege, wooden houses were used by the navy and wood beams were burned to cook with.17 Due to this situation, it cannot be expected that any evidence of housing components or customs transferred from Byzantine civilian architecture to Ottoman housing culture would be found; rather one needs to imagine a civilian architectural infrastructure in which that the beams were ripped out and the brick buildings were damaged. Even though of a different century and geography, the Byzantine houses that were found in Karakabalı, which had no floor beams and which consisted of only partially standing masonry structures, can give an indication about the housing that the Ottomans encountered in Constantinople (Figure 1).

After the conquest, traces of Byzantine wall craftsmanship can be seen in the houses with gable roofs depicted in Onuphrius Panvinius’s drawing of Sultanahmet Square (Figure 2), dating from the middle of the sixteenth century. (e.g. the semicircular openings in the wall rather than skylights or windows, the rows of bricks continuing on the arches, and horizontal brick beams on the facade.) Even one century after the conquest it is possible to see a parallel depiction in Panvinius’s drawings of the Tekfur Palace and the reconstruction of the Mistra house facades (Figure 2).

While Ottoman houses in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries cannot be described with much accuracy, it is even more difficult to discuss Ottoman housing before the conquest. However, it is obvious that the housing culture which came with the newcomers was perhaps the most important factor in the Ottoman-Turk house components. Thus, it is necessary to discuss Ottoman housing customs before the conquest.

The approaches of research into the roots of Ottoman-Turk housing can be examined under two headings: the hall-based approach and the room-based approach. In the hall-based approach there were different styles: (1) halls connected the rooms in a straight line (hayat), (2) iwans in between the rooms, with the formation of an upside-down T-shape, or (3) the rooms being connected from a central position. It is possible to speak of a synthesis of the housing cultures of the native people and the Turks. The Hittite hilani, the Arab beyt, the Mesopotamian tarma, the Iranian tala and the Turkish hayat were all dealt with as varieties of the same system. In this sense, there are some researchers who have approached the central hall-system either as a development influenced by the West or as the most developed condition of an evolutionary process.

The room-based approach pursues more direct and practical connections. According to this approach, rooms evolved from tents. In fact, the word oda (room) is derived from the word otağ (tent).18 The Ottoman way of writing oda is with the Arabic letter tı and not the letter dal, thus confirming the oda-otağ connection. When the connection between tents and rooms is accepted, an architectural component that is prepared on the basis of a central plan and which has four facades can be arrived at. The rooms of Ottoman-Turk houses, exactly like nomads’ tents, are independent and multifunctional. In fact, the portable rooms that Yoruks use can still be seen today and have been evaluated as a transitional type by researchers for the relationship between tents and rooms. These light-structured buildings can be made permanent if necessary.19

According to the room-based approach, it is possible that Ottoman-Turkish houses emerged as a result of the transformation from nomadic life to settled life. However, when examined chronologically, it is possible to suggest that Turks started to live a settled life with the first beyliks, established by the Anatolian Seljuqs after the Battle of Manzikert, several centuries before the conquest. At this point, giving the term Türk Evi too wide a scope will become problematical. This is because the Ottoman chronology was different from that of the Seljuks, and for this reason when the question is ‘which Türk Evi is being discussed?’ the answer ‘Ottoman-Turkish house’ is more correct. The period of Anatolian beyliks was one in which the nomad culture brought by the last Turkmen who came to Anatolia was still strong. For example, Ibn Battuta, who traveled to Anatolia in the beylik period, described the accommodation provided to him by the Birgi bey thus:

They sent me a dome-shaped tent called a bargah. A bargah is set up on logs that are placed next to one another, and these are covered with felt. A hole called a badhenç is left at the top for light and air to get in and if necessary, this hole can be covered; this is like a house...

The description of an open-topped, house-like tent given by Ibn Battuta is like the kerekü,20 a domed or conical shaped tent used by Middle Eastern nomads. Moreover, Ibn Battuta visited a medrese student whom he encountered before meeting with the Birgi bey:

He acted as our guide and took us to his house, which was in a vineyard; he hosted us on the roof that was shaded by branches. It was one of the hottest days of summer...

This description from Ibn Battuta makes one think that he had been brought to a version of the housing structure known as a gurfe, which will be mentioned below in connection with civilian architecture in Istanbul. These kinds of examples demonstrate that practical, mobile and flexibly-structured units, which were part of the Central Asian inventory, were used in West Anatolia in the fourteenth century. Another manifestation of the room-based approach can be seen in köşk (pavilion/mansion) architecture. This type of housing should be referred to within pre-conquest Ottoman housing architecture; the köşk (pavilion), a structure that was open on all four sides and detached, was in general raised, creating its own central location. It is known that some köşks existed in the pre-conquest period (Figure 3).21 However, these examples were not part of the urban texture, but consisted of mansions that were set apart and which belonged to the administrative class. Despite this, these examples are important sources for explaining the housing culture of the city at this period. The fact that that these raised köşks, even though they were of modest dimensions, existed in the city leads one to think that they fulfilled the role of gurfe housing that most likely emerged in post-conquest Istanbul and which will be mentioned below.

In conclusion, it is highly likely that a civilian architecture accumulation developed within the room-tent relationship in the Ottomans after the conquest and the physical environment of this accommodation culture took place in the rapid development and settlement program of Istanbul.

Information Gathered from Visual and Written Sources about Istanbul Accommodation after the Conquest and in the Sixteenth Century

According to records in the 1478 tahrir (census) records, it can be estimated that the population of Istanbul at this time was 70,000.22 This would mean that after the conquest the population of the city increased by at least 10,000 or at most 40,000 in 25 years; this large an increase in the population is the equivalent of the population of a typical city in the fifteenth century. Furthermore, this population rise was not a one-off occurrence; rather the population continued to increase throughout the sixteenth century. It is estimated that only a century after the conquest, the population of Istanbul was at least 400,000.23 Such a large population movement demonstrates the extent of the planning and construction in Istanbul. After the conquest Mehmed II started a massive urban planning initiative to increase the population of the city. He was especially sensitive with regards to property in the city: instead of giving existing properties to the newly arrived migrants, he put them into service as mukataa (rental property). However, he later changed his mind on this matter. In fact, it is possible to talk about a clearly encouraged immigration movement. Beyond what Mehmed II was accustomed to, the fact that he wanted to give the conquered property to immigrants as mukataa demonstrates that he was concentrating on a statist-centralist model. This attitude supports the idea that the town development and dwelling plans were being made deliberately and under control. For example, the most important feature of Fatih Külliye was that it was designed as a self-sufficient structure, functioning like a city. Scholars were invited to come here from the East and the West, and some properties in and around the külliye were even given to them. It can be assumed that the geometric nature of the külliye’s design, as compared to previous Ottoman külliye (for example Yeşil Külliye) (or even later külliyes; for example the plan of Süleymaniye Külliye is more organic than that of Fatih Külliye), is in agreement with Mehmed II’s centralist attitude. It is possible that this situation, which was applied in the settlement policy, was also reflected in the physical aspect of settlement.

Kritovoulos, one of the historians of the period, describes the efforts made in town planning and settlement in 1458:

Bringing people of learning, science, art and wealth, as well as those working in trade who have influence, a good reputation and wealth, [Mehmed II] allowed them to build bazaars, inns, shops, Turkish baths, magnificent houses, mosques and chapels; he ordered them to build impressive buildings to the degree of their wealth and power.

The encouragement that Mehmed II gave to those around him can be best seen in the public improvement works carried out by the viziers. The mosques constructed in the name of Mahmud Pasha, Rum Mehmed Pasha and Murad Pasha are not grand mosques; rather they are of the T-shape mosque plan. As is known, this kind of mosques did not only serve as mosques; they were centers that were used by social organizations like the ahi community and for that reason would probably have appealed to the new settlers. It is for this reason that the preference of the viziers in planning mosques can be examined as an example of Mehmed II’s town planning and settlement policies, as well as his centralist planning approach.

How did town planning and settling data affect the civil architecture of Istanbul? How should the phrase ‘magnificent houses’, as used by Kritovoulos be understood? Kafiri houses, which appeared in the Byzantine period and were used by the Ottomans, played a huge role in meeting housing needs. However, with the increase in the city’s population to 400,000 (or at least 340,000) 100 years after the conquest meant that the housing needs could not be met by the Byzantine houses alone. For this reason, the time of the conquest and the following century present perhaps the most important environment for the formation of the infrastructure of the Ottoman-Turk House tradition. The Ottoman poet and historian Hadidi tells us in Tevârîh-i Âl-i Osman:

Forcing to move many cities from Karaman/not only one village but the entire city

They give both vineyard and garde/each can built high buildings.

In rough translation: “By exiling many towns from Karaman, not a village but a large town, they give them vineyard and garden, and they build tall houses”

Terms like beyt-i ulvî, hane-i ulvî, gurfe-i ulîyye, which occur in fifteenth-century vakfiyes, mean the same as Hadidi’s ali ev (exalted house). Working from this, it is logical to expect to find evidence of ali, tall houses, or rather houses with upper stories. This kind of an approach supports the tendency of constructing tall mansions that were mentioned above.

Vakfiye, vesika (certificates), mühimme (register) books, court records, and literary works of the period, as well as notes from travelers provide information that is rich in content yet hard to verify or classify. However, it is possible to arrive at important conclusions by surveying these sources. There are visual sources that support the written documents. Miniatures by Ottoman nakkaş (artists) and descriptions of Western travelers to Istanbul offer some valuable ideas about the civil architecture.

The vakfiyes are the records kept about the properties of the waqfs. With the help of these records, researchers can obtain information about the location of property and land, as well as the types of property and some physical features, and the qualities of the properties and land. By comparing two vakfiyes, (the Fatih vakfiyes dated between 1463 and 147024 and Istanbul Vakıfları Tahrir Defteri - Istanbul Waqf Tahrir Records -dated 154625) civilian architecture and the changes in this architecture during the century after the conquest can be traced.26 The first and maybe the most important difference between Istanbul Vakıfları Tahrir Defteri (henceforth İVTD ) and Fatih Vakfiye (henceforth FV) is that while, with a few exceptions, one of them lists small and medium-sized vakfiyes of ordinary people, the other records the components of the sultan’s vakfiye in different districts. Thus, the tahrir records have a character that has more in common with the particulars of civil architecture.

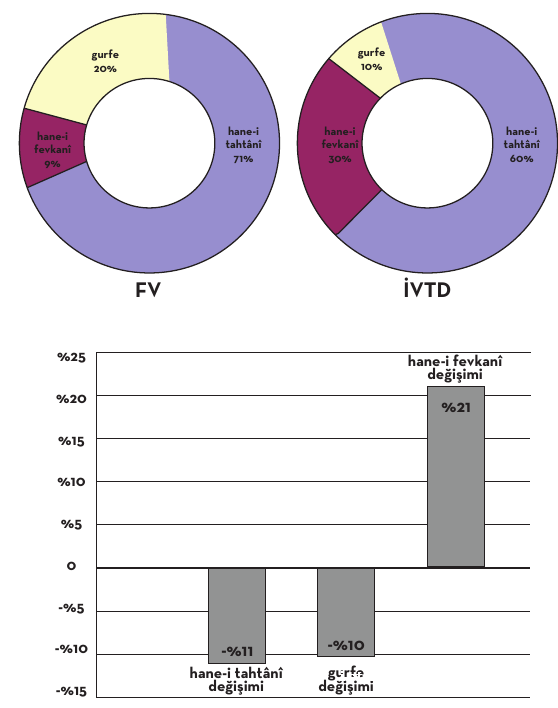

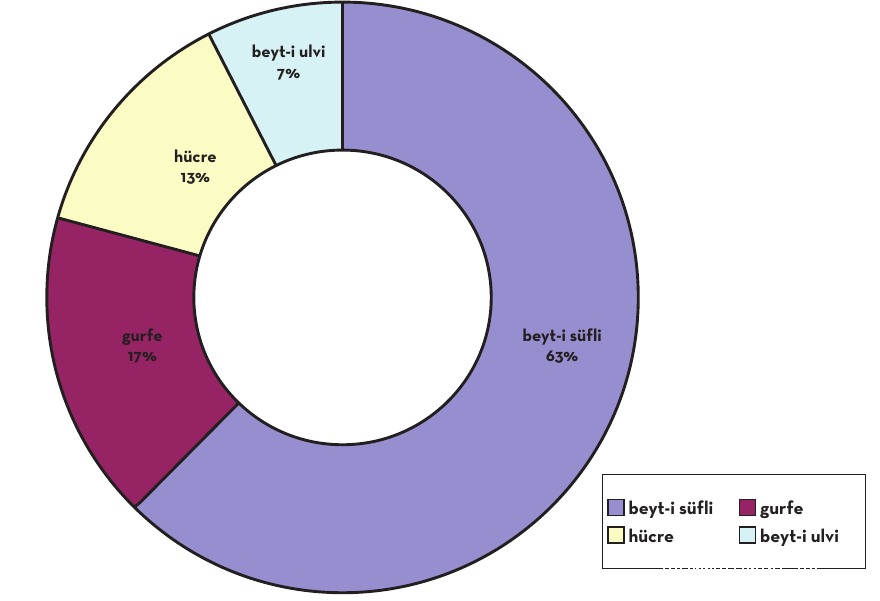

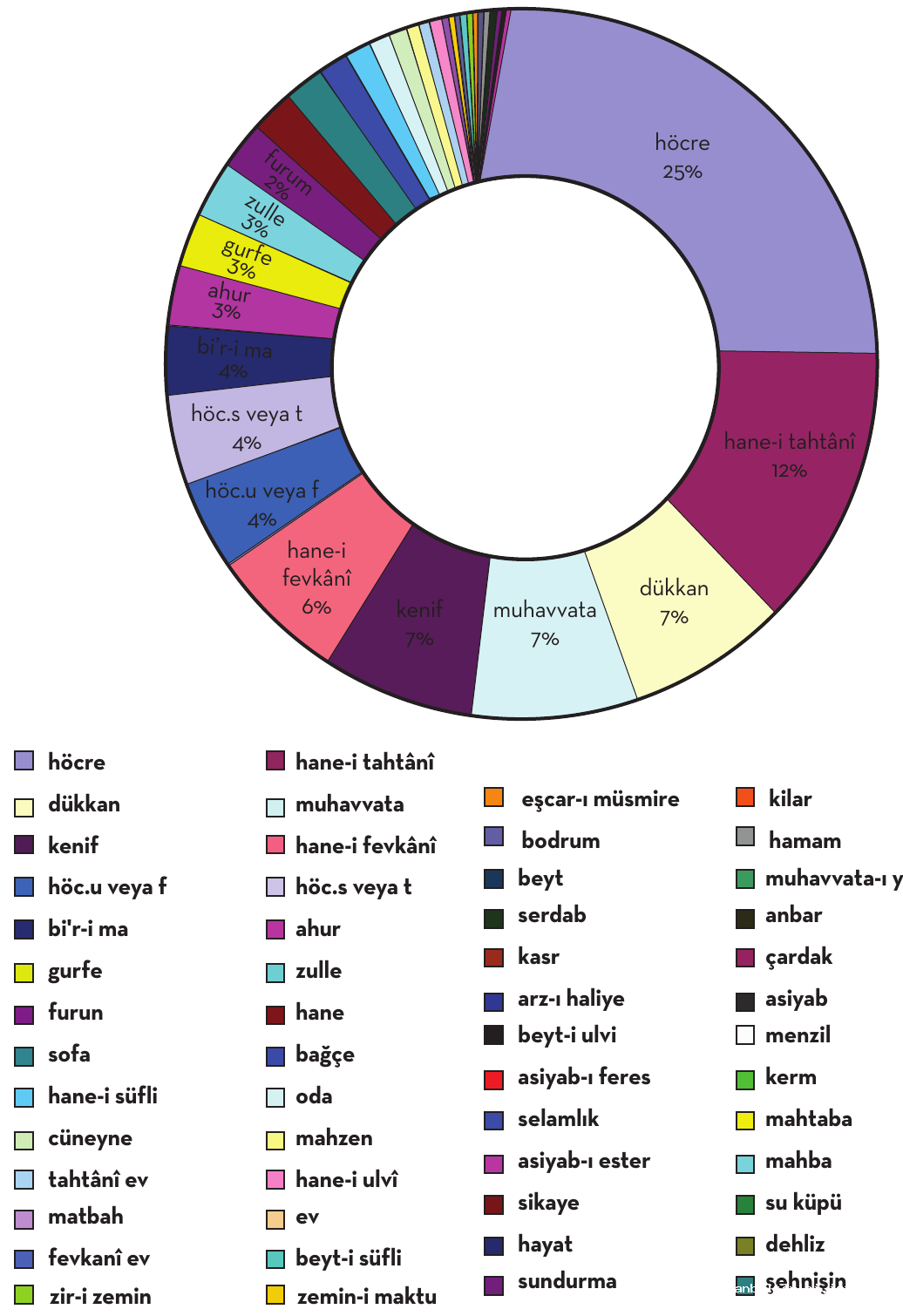

FV and İVTD are different in scope. While FV includes 457 menzil,27 the tahrir record books include 2,431 menzil. Additionally, there are more waqfs in the tahrir records. As mentioned above, the waqf owners were also different. Despite all the risks it is possible to compare the two waqfs and observe increases and decreases in their units over time. From the aspect of understanding development in civilian architecture of the era, comparing a housing census carried out ten years after the conquest with one from the middle of the sixteenth century may produce some robust indicators in an environment in which there is a paucity of physical or primary data, despite the aforementioned risks. For this kind of comparison, units in the two waqfs can be expressed in the same form. When synonyms like tahtânî-süfli, fevkanî-ulvî or beyt-hane-ev are put into the same category, they form some common values that enable comparison. Accordingly, units that are common to both waqfs and the ratios between them are shown in Figure 4.

The term hane-i tahtânî refers to housing units on the lower level, while hane-i fevkanî refers to housing units placed on upper levels. The term gurfe, which will be explained later, in the present argument can be considered as an upper story unit. Thus when evaluating the comparison given in Figure 4, it is obvious that FV indicates a single-layered city and İVTD indicates a city of many multi-storied units. Upper floor usage increased throughout the city. However, why was there a decrease in the number of gurfe, which has been described as an upper floor unit, and how can this be explained in an environment in which settlement in upper floors increased? The most logical explanation is that the gurfes were transformed into hane-i fevkaniyes, or in other words, into upstairs houses. The situation depicted in the İVTD documents, dating a century after the conquest, has more in common with the dual-storied image that had formed in minds for the Ottoman-Turk house. In this situation, it is possible to consider the gurfes as part of the evolutionary process that eventually led to this image.

Other than the increase in the number of floors during and after the conquest, what else can be considered as specific to the civilian architecture of the period? For example, the term muhavvat(a)28 which can be found in the sources is interesting. Muhavvat means a yard surrounded by walls on all four sides, but it is so frequently encountered in İVTD that it suggests some kind of life closed off from the street. Indeed, there is mention of inner and outer muhavvats. For example, the phrase in Yusuf b. Abdullah’s vakfiye, which is number 1823 in İVTD: “hanehâ-i tahtânî 2 bab ve sofa ve kenif der muhavvata-i dahiliyye ve hücre ve kenif der muhavvata-i hariciyye der mahalle-i…” (in the lower section of the building there are two sections, a hall and a toilet in the inner section and a room and a toilet in the outer section) the nature of the inner and outer units mentioned in the vakfiye are debatable. While there is a room and a toilet in the outer courtyard, the actual residential units are in the inner courtyard. The vakfiye of Hacı Turahan b. Abdullah, which is number 33, states: “evladlarına ve evlad-ı evladlarına neslen ba’de neslin müte’ehhil (evli) olanlar iç evlerde olub mücerred (bekâr) olanlar taşra havlıda (avluda) olan evlerde olalar…” (While the married couples stay in the inner yard, single people reside in the outer yard). This record is important evidence for understanding the relationship between social conditions and privacy. In the vakfiyes it is recorded that the gurfes and hücres (rooms) were recorded over the muhavvata door. Also the blank façade that the muhavvatas presented to the street is important from the aspect of the comparison of the upper floors and the lower floors, which will be made below. In a drawing dated 1574 of the Hippodrome and Hagia Sophia, known as the Freshfield Folio, the muhavvata wall of a palace and the unit above the muhavvata door are in agreement with the description in the vakfiye. It does not appear to be very difficult to find such a correlation between the muhavvata and privacy. It is significant that instead of using the term havli, which is derived from the Arabic and means ‘yard’ in Ottoman Turkish, in İVTD the term muhavvata, meaning a place surrounded by walls, is preferred.

Another expression that makes the relationship between muhavvata structures and the matter of privacy clear comes from Dernschwam, a German envoy:

Turkish people do not go outside at night. Everywhere is silent and calm. Contrary to how we live, there is no singing, noise etc. After all, houses are not on the street, they are at the back.29

Sanderson, a British traveler, came to the following conclusions about the mansions and palaces of viziers:

The mansions and palaces of the viziers are magnificent and surrounded with high walls; they look more like cities than palaces. From the exterior they are not at all appealing, but they are decorated with the most valuable possessions on the inside. Turkish people say that they do this to meet their daily needs, not to please those who passing by. They claim that Christian palaces are oriented towards the exterior, while on the inside they are not that attractive.30

Finally, the opinion of the German traveler Schweigger is in agreement with the two accounts given above:

Even though the houses of pashas and respected men are large and spacious, they are quite poor in appearance; the garden is surrounded by walls higher than the roof. All the rooms are downstairs. In the houses of the great beys there is a spacious living room where they welcome their guests and discuss important issues. These buildings resemble a large monastery to a certain extent; they are suitable for contemplating issues and producing ideas in an isolated and quiet environment; the noise of horses, carts and people cannot be heard.31

These expressions and the descriptions of the blank muhavvata wall are quite interesting. These houses which were not directly on the street indicate the absence of houses that overhung the street, perhaps the most significant feature of the Ottoman-Turk houses, in the sixteenth century. Thus, when discussing the period during and immediately after the conquest, one should imagine more withdrawn and private houses.

The idea that the brick structures remaining from the Byzantine era indicate a substructure has been suggested above. In support of this, 47 storehouses and basements were counted, meaning that there was one storehouse per 10 menzil. In İVTD, the number of storehouses and basements is 247, and although this number is much higher, it gives the same ratio of one to ten. In the Ayasofya Vakıfları Tahrir Defteri32 (henceforth AVTD) and even in İVTD, the word kafiri is used to designate these units. As far as the material used for these, it is highly likely that they were built out of brick, and it is again likely that these were inherited from the Byzantine era; the consistency of the facts reported about them in the vakfiye records can be interpreted as the result of efforts to protect the infrastructure.

Hücres (cells/rooms) are units of the accommodation culture that are encountered frequently in the written sources and about which interesting details are provided. Like the hücres that are listed in the menzils, there are also hücres that were donated en masse and which were allocated to people who did not live in a family setting. Not only are they encountered in just one place, in parallel with the argument above, there are hücre which are quoted as being dedicated to bachelors. In the vakfiye number 303, owned by Daye Hatun, a wafq that is described as Höcerat-ı Azeban 7 bab der mahalle-i yahudiyan (7 hücres for singles in the Jewish neighborhood). Again in vakfiye number 136, located in the Firuz Agha neighborhood in which there was a small mosque, 33 of the hücres are referred to as hücerat-ı gureba (rooms for strangers). There is also an example of hücre that were named after the religion of the founders: In the vakfiye of Hüseyin Agha, in the Çelebioğlu neighborhood, which is numbered 116, 18 doors had hücerat-i Yahudiyan (rooms for Jews). Usually, collective hücres were reserved for travelers, soldiers, singles, Jews and members of tariqah. However, in the neighborhood of the Aşık Paşa Mosque, the vakfiye numbered 1626, which is related to a location near the mosque, includes three cells designated for nisa-i salihat; this is quite interesting because this term means salih (faithful, pious) women.

Dernschwam, after describing the masonry structure of Elçi Han, describes the hücres as follows:

Each cell is 16 ayak (feet) long (approximately 5 m.) and 16 ayak wide… the interior walls are made of a single thickness of bricks. Each hücre has a small brick oven …. the floor is covered with bricks. In accordance with their custom, four walls of the celss were covered with hımış, i.e. roof, then constructed as walls.

In İVTD there is a record concerning the fact that in waqf 1393, 14 lower-floor hücre ihrak-ı kebir (grand fire) were lit and that mukataaya was given in their place. The fact that 14 hücre burned down brings us to the conclusion that they had a wooden structure. Another physical feature of the hücres which emerges from the vakfiye records is that the hücres were smaller than houses. The record of the 2013 vakfiye in İVTD reads as follows: “In the lower floor there were four hanes (houses). Now there is a total of 7 hücres.” If four houses can be transformed into seven hücres, then the size of the hücres recorded in this vakfiye is half the size of the former houses.

What can be known about the floor plans of houses from this era? There is some evidence of houses with hayats (courtyards), linear hallways or T-shaped plans, that is, essentially an iwan structure, as mentioned above. The French traveler, Philippe du Frense, described (Sokollu) Mehmed Pasha’s palace while he stayed in Burgos (Lüleburgaz) on his way from Edirne to Istanbul:33

When one goes up three or four steps in the palace garden, a revak (portico) that surrounds the palace can be seen… There are more than eight rooms, lined up side by side, narrow and small; almost every Turkish house is made in this way…

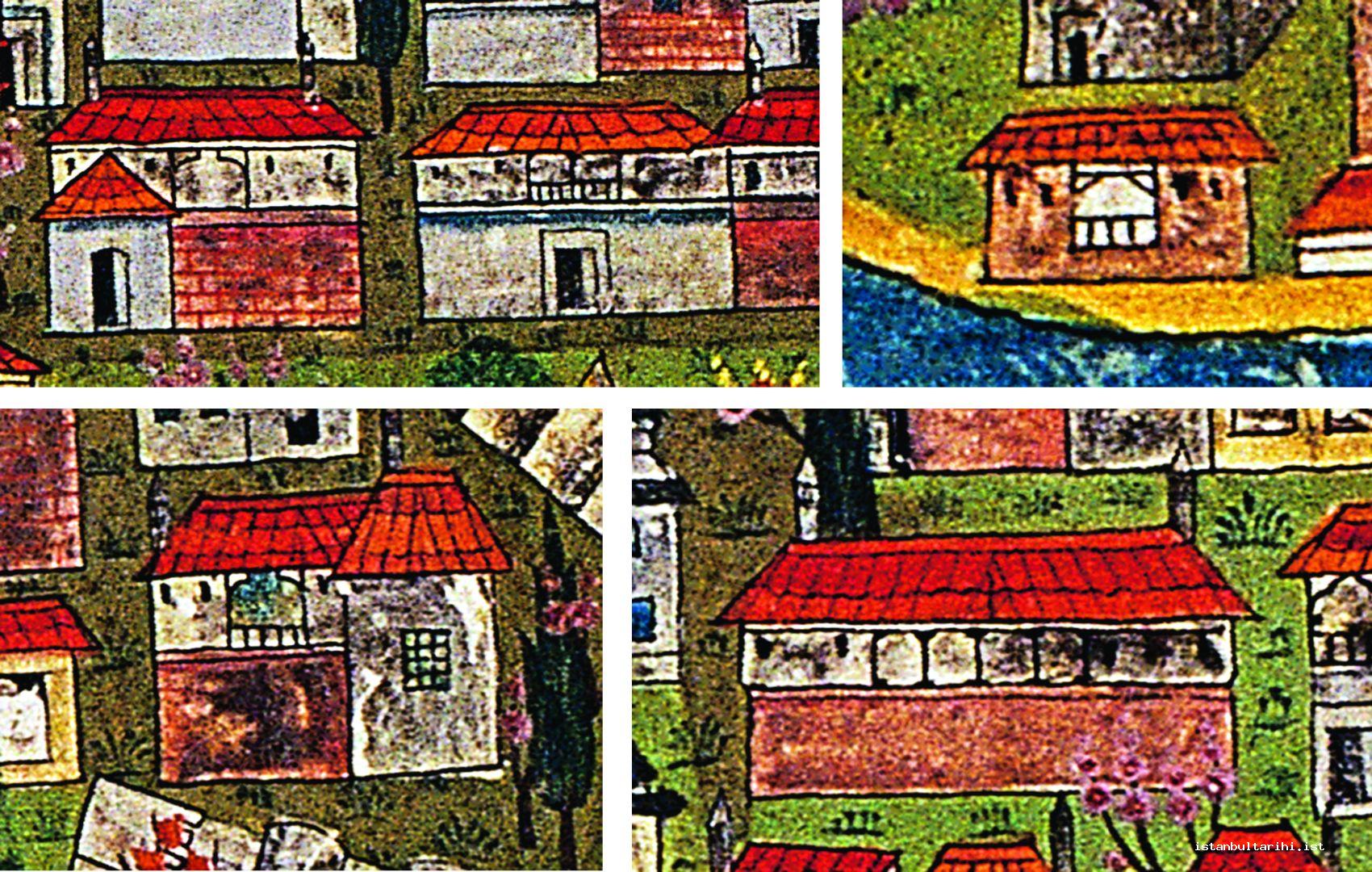

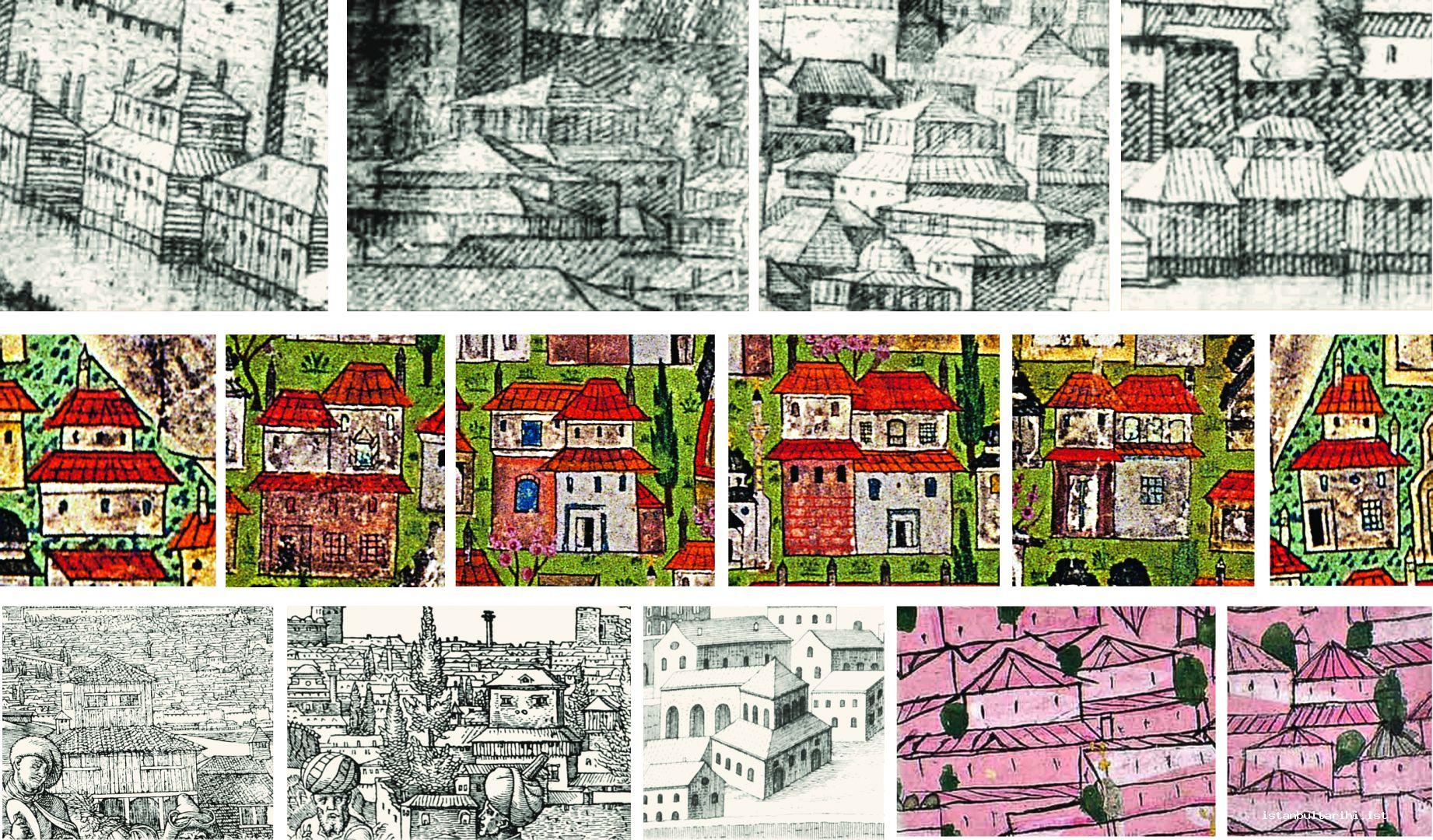

From this, even though this description is not about an Istanbul institution, it can be understood that there were Turkish houses with long verandas and linear hallways. In addition, it is well recognized that there were examples of an iwan-hallway between two rooms. In İVTD number 445, the vakfiye of Mustafa el-Katib is recorded as İki beyt-i süfli ortası sofa ve bir gurfe ve ahur ve kenif ve bağçe (a hall, gürfe, stables, toilet and garden between two rooms). The statement here is quite clear; a hall room connects two residential units horizontally. Houses that are in keeping with this description can be made out in Matrakçı’s drawing of Istanbul (Figure 5).

Dernschwam describes a konak yeri (guesthouse) in Niš as follows:

The konak yeri was the house of a deceased pasha; it was like a big village house. It had a big door. Near the door was a room that had an oven in it and a barn for horses. Across from the door was a wooden house that was built on the walls of a dilapidated house. The barn had not yet been completed. The house had two rooms with ovens and there was a hall in the middle where people ate their meals. It was a very plain building, no embossing or ornaments. Across from the house, towards the mountain, was a second house, standing in front of the house we were staying in. The house we were in had a beautiful view, while the other looked on the street. This was also a simple wooden structure.

An example given by Dernschwam of houses outside of Istanbul, but in the same period of time, and the description of Istanbul by Matrakçı supports a type of plan that includes a middle hallway.

Despite these examples of housing structures with hallways, it would be unwise to suggest that a housing plan based on hallways was standard in this period. This is because a number of menzils in İVTD34 consist of just one house. Additionally, there is a large number of waqfs which are composed of single-story houses within a muhavvata, as it was not necessary to provide a closed environment for horizontal circulation. The vakfiye records examined make one think that the basic component must have been the oda/hane for these periods.

There are some indications concerned with the multiple functions that the rooms of the houses in this period were used for, in parallel with the Ottoman-Turk housing traditions. Dernschwarn emphasized the multiple tasks of the rooms: “…In these houses, people sit on the floor. They sleep on the same floor where they eat at night…” In İVTD, we encounter many houses that were being used as muallimhane (home for teachers) or houses that were next to one another, or one above the other which were also used as muallimhanes. The tahrir officer recorded changes in the 297 numbered vakfiye as follows: “…one of the houses above the barn has been made into a muallimhane.” In vakfiye 1832, the lower portion was allocated as a residence for the muezzin, while the upper floor was allocated to teachers: “Muallimhane fevkanî ve beyt-i tahtânî beray-ı sükna-i müezzin.” (The upper floor was the muallimhane, while the lower floor was a residence for the muezzin). Schweigger provides a description that supports these records:

Both in Constantinople or in other cities, there is a large number of elementary schools that educate boys. Anyone who thinks they are suitable for the teaching profession can teach. There are no special buildings or schools for this purpose. A teacher can accept students everywhere, even in their own house if they want.

As a result of evaluations made concerning Byzantine houses, there is visual evidence that makes one think that the Turks most probably encountered the Mistra type of housing when they arrived in the city. Although Matrakçı and Lorichs depicted the city in completely different ways, both indicate gable-roofed buildings made of stone with triangular pediments (Figure 6).

Material Preferences

Apart from what the Byzantines left behind, according to the data which will be examined below, the strongest probability about material preferences appears to be wooden structures or brick/adobe filling. Visual sources also support this argument (Figure 7).35 One of the subjects that many sixteenth-century travelers describe in a similar way is that the buildings of the Turks or those of Istanbul houses were neglected and very badly constructed. This is an expected response.

First of all, many of these travelers were diplomat aristocrats who came to the Ottoman Lands with prejudice due to the fact that their countries were at almost continuous war with them. In particular, German travelers can be seen to have made the most negative evaluations. In addition to this, the fact that they were not able to perceive the temporary nature of the buildings that they saw in the Ottomans due to having a different worldview. It is necessary to wait until the Modern era for Westerners, or maybe Le Corbusier’s oriental journey to discover that the clear and uncomplicated structural-material approach, simplicity in housing was justified. If we put subjective judgements to one side, the comments made by travelers include some valuable data concerning the use of materials.

Busbecq states in his first letter, dated 1555, that the Turks in Buda had settled in former Hungarian palaces without renovating these palaces; for Turks, giving importance to such things was a sign of pride, arrogance and conceit. As a result, Bucbecq states that they avoided grandeur in their buildings. “For them a house is like an inn for a traveler.” For this reason, Bucbecq says that it was difficult to find luxury even in the houses of the wealthy; he tells us that ordinary people lived in huts. In addition, the streets were too narrow to produce a pleasant scene.36

Dernschwarn’s comments on this matter:

In any case Turks are not constructing any new buildings. In addition they have not protected the beautiful old houses. Almost every house located inside the old, demolished city walls are single-story buildings made with poor materials… As the wooden houses in Istanbul are not as solid as the houses in Suebya, Baverya or other districts, in order to prevent fire spreading the janissaries tear down these houses with ease. The firemen demolish the wooden and adobe hut-like houses that stand in the path of the wind as it blows through the narrow streets….

Schweigger’s comments about Istanbul on this matter are:

The houses in the city are poorly built and neglected. Most of them have been constructed without using lime, only with mud and clay. The houses are low and receive little light. In general, there is a narrow window in their rooms like the ventilation holes in our basements and barns. Turks do not know what a stove is; they heat their houses with fires. Even though the rich people live in houses made of lime and stone, these are not like houses in Germany. I have not seen any pinewood being used in houses; beech is used for everything. The roof is first covered with wood, and then it is covered with tiles that are laid in a grooved pattern. The house is constructed so that it receives light through the roof… Turks are usually content with small places, as they have no livestock but horses, and their belongings are few. If someone has a barn for the horses, then two rooms are enough for them.

Moryson, a British traveler, says the following:

The streets of the city are narrow and have pavements on both sides. Houses are generally made out of brick, stone or wood, or with backed soil in the shape of bricks. These houses, which can be as high as two stories, have flat roofs and are covered with tiles. There are wooden shutters for closing the large windows at night...37

Gyllius has the following to say:

I had the hope that I would easily pick up the traces of the old city, however this barbarian people had destroyed the old and undoubtedly legendary monuments to make their own worthless houses or to cover it in their barbarian structures….38

What is interesting is that the travelers record that the Turks had very positive opinions about their own houses and that they loved these residences. In fact, Turks did not like the Westerners’ houses. The traveler Fresne notes that: “….the houses are so practical and beautiful that they feel very sorry when they have to leave them.”39 The note written by Sanderson, which was mentioned in the muhavvata section, should not be forgotten:

Turkish people say that they do this to meet their daily needs, not to please those who passing by. They claim that Christian palaces are oriented towards the exterior, while on the inside they are not that attractive.

In his tezkire Latifi mentions the beytler ve kasırlar (houses and mansions) of the city under the title Sıfat-ı ziynet-i Büyut ve Kusur-ı der in Şehr-i Ma’mur ve Meşhur. Saying “Ve saray-ı cennet-ârânın büyut-ı tabakatı ve eyâvin-i gurafatı âlisin benat ile numune-i hur-ı maksuratdır.” He demonstrates how Westerners and Easterners see the same city from different points of view.

Gurfe

The term gurfe that has been mentioned several times and which appears frequently in FV is an architectural element that must be clarified in order to understand the civilian architecture of this time. It can be understood that gurfes were a flexible structure that could easily be placed, for example, on barns, over doors, arches, storehouses, shops, bakeries, hücres, hanes, or even on top of another gurfe. This makes it unlikely that the gurfe were made of brick. In fact, there are some vakfiyes that make it clear this was not the case. In İVTD number 1541 the phrase “… gurfe-i masnu’a ez elvah…” and in number 1149 “…gurfe ez-elvah…” we can understood that gurfes were made of boards, that is wooden boards. However, the terms levhî and ez elvah should lead us to the conclusion that these were covering materials, not structural materials. When one remembers that there was no way to industrially process wood, the importance of precut wood comes to the fore. In this case the phrase levhî gurfes leads us to the conclusion that this was a product produced with care. It is likely that levh constructions were much lighter than the wooden structures of the early Ottoman period which were filled with rubble, stone or brick/adobe, suggesting that in terms of material, gurfes might have differed from the structures upon which they were built in terms of material.

When the visual sources of the period have been examined from the written sources until now, there is an upstairs structure that appears in almost all of the visual sources, and which can be found in both Ottoman and Western sources. The frequency with which the gurfe are found in the written sources and is parallel with the frequency of the appearance of the upper floor structure in the visual sources. It is interesting that despite the fact that visual sources were created with different techniques and different details, the upstairs structure which we are currently discussing, that is the gurfe, appears as a common factor (Figure 8).

There is a clear difference in the gurfes given in FV and İVTD. Among all the structural units of the fevkanî units, there is an increase from 9% to 30% from the former to the latter vakfiye. There is a decrease from 20% to 10% for the gurfes. How can we explain these great changes? The first question that should be asked is how did the gurfes emerge? As has been mentioned several times previously, it is not very likely that the Ottomans appropriated some of the wooden units from Byzantine civilian architecture. In a city where sakıfsız beyt (roofless houses) were found after the conquest, the existence of wooden units like the gurfe does not seem possible, particularly if we consider that the Byzantines tore down and burned even the beams of the buildings when under siege. At the same time, there is a large number of structures referred to as “kâfirî buildings” that had been inherited from the Byzantines; it is most likely that these were of brick. Particularly in AVTD, there are records about buildings being kâfirî, that additions were made to these and that these buildings that were constructed later were recorded. It therefore seems possible to ascertain what proportion of buildings mentioned in the register from AVTD were kâfirî. In AVTD, the term is used in the following situations: “a room made afterwards and a single-story house that is a kâfirî building are located in the mentioned neighborhood”, in the old Bozahaneler Neighborhood; “the kâfirî building with a new roof, located in the aforementioned neighborhood, is mentioned belongs to the waqf” in Hacı Timurtaş Mescidi Neighborhood; in the same neighborhood “5 stores and 13 houses belonging to the Hoca Kutbuddin’s Waqf – a kâfirî building with a new roof, the store and the house of Faluzcu Hüseyin Foundation – a kâfirî building with a new roof”. These expressions clearly demonstrate that the newcomers intervened in the Byzantine civilian architecture. As can be observed in the AVTD, Ottomans altered roofs and they added some odas. They took advantage of the existing masonry substructure to the extent that they could. Even approximately one century after the conquest, references to cidar-ı kâfirî can be encountered in İVTD, in vakfiye number 1438. In this case, it would be reasonable to evaluate the gurfes as a preference in Ottoman civilian architecture, who renovated the buildings, in particular the roofs.

Another situation that should be examined is whether Ottomans made additions like the gurfes as a result of Sultan Mehmed II’s “planned settlement” movement after the conquest. Were the alterations made by the Turks done according to their personal preferences or were they part of the town planning and settlement movements, making a contribution to the construction of accommodation, alongside the construction of mosques and medreses? It is known that Sultan Mehmet II personally took interest in public improvement projects. According to some sources, like Tursun Bey, Kemalpaşazade and Kritovoulos, there are indications that Sultan Mehmet II involved himself with the designing of the new palace during the construction process. In fact, Bitlisî describes the palace as a group of excursion pavilions that made it possible to survey every corner of the growing capital city and the sea, teeming with boats coming from different parts of the world. The term used in this description is gurfat. In this case, we can ascertain that some gurfes were built by the central administration. The most important data that illustrates how the gurfes in vakfiyes were made with the help of the waqfs is the way in which this information is stated in FV. Expressions such as gurfe bina olunmuştur (a gurfe was formed), gurfe yapılmıştır (a gurfe was built), gurfe vaz’ olunmuştur (a gurfe was settled) and gurfe tarholunmuştur (a gurfe was set up) were used in FV for gurfes. The other use of this term (in the meaning of a building) is found as dekâkini sultani (sultan’s shops), which were most likely constructed by the state. Such expressions were not used for beyt-i ulvîs, which appear much less frequently than beyt-i süflis or gurfes. Terms like tarh olunmak and vaz’ olunmak provide information about the structure of gurfes as well as suggesting that they may have been constructed by the state; the fact that words like tarh and vaz were used supports the idea that gurfes were units made from wood.

CONCLUSION

The conquest is a great event in helping us to understand the Ottoman-Turk housing concept, and is a milestone for Istanbul, marking the beginning of an era of social, political and urban renewal. It is easier to speak of development in the centuries after the conquest. However, the Ottoman conquest was more of a breaking point, a jumping off point, a planning point than a developmental situation. In order to understand the accommodation culture of the sixteenth century, one which has been focused on a great deal as the brightest century of the Ottoman era, but which is not very satisfactory from the aspect of what is known about the civilian architecture, more realistic results could be attained by carrying out studies by seeing the conquest as an opportunity, instead of making idealizations through which the buildings of later centuries were reflected backwards.

It is not easy to talk about only one housing style or one tradition in the sixteenth century. From the aspect of the languages spoken in the city, Istanbul at this time resembled ancient Babylon.40 Even the variety of nationalities that were brought to the city after the conquest is common knowledge. Moreover, the ratio of hücre tesisleri (cell/room facilities) increased in the sixteenth century. It is likely that the number of rows of hücres which were leased by people who did not form families (bachelors, strangers, çiftbozan reaya). In İVTD, even if rarely, multi-storied mutabbaka houses are encountered,41 as if the tradition of insula was still persisting. Another interesting structural occupation of that period, although fewer in number, were large stone pavilions with Turkish baths, towers and structures to mark menzil (stages on a journey). Despite all these exceptions and the overwhelming cultural richness, some main themes can be found in written and visual sources which provide clues about accommodation styles and a culture.

When İVTD is examined, the increase in the number of fevkanî houses and the decrease in the number of gurfes which occurred during the same interval of time, and the fact that the rise and fall were both dramatic, should be interpreted as the transformation of gurfes into fevkanîs.42 This situation indicates the gradual development of the upstairs level, one of the distinguishing features of the Ottoman-Turk house, between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Since gurfes were levhî and tarh olunan constructions, led to a tension between them and the brick/adobe filled downstairs walls. It could be suggested that the classic Türk Evi, with a tension between the lower floor and the upper floor, and the roofing of the gurfe which were placed on the kâfırî buildings, creating an esthetic of tension, if nothing else, was thus first implemented in the new city.

Two visual sources, one from the West, one from the East, from the middle of the eighteenth century, support one another and indicate the main trend in accommodation tradition, which can be seen to have firmly dominated Istanbul.43 Elements of the familiar image of Ottoman-Turk houses that will be seen in later centuries’ gravures started to be formed. In general, the houses were of the fevkanî; this building, which depicts the main features of housing in Istanbul, was constructed from lighter beams which were plastered around the sides; with some boards, a hipped roof and large, hand shaped windows and, the almost mandatory roof window, this type of building can be clearly seen in the visual sources (Figure 9) The sheltering structures that emerged and developed after the conquest, which were examined in this study, were transformed into monotype houses after 300 years. Still, the eighteenth century Ottoman houses did not have exterior components that encroached on the streets, nor did they tend to have ground floors that were not secluded but communication with the street. Additionally, the fact that skylights had not yet fallen out of use meant that the rooms of these houses could receive light even when the regular windows are closed or blocked for privacy.

As a result, a housing custom that is not expected from the idealized Ottoman-Turk house image for at least 100 years after the conquest emerges. Behind the high courtyard walls, odas which got their light from the roof, a large percentage of which were single-storied, perhaps freely distributed among courtyards, closed off and with strict privacy, in some places surrounded by a porch like a zulle (shaded area), independent hanes, come to the fore as the determining component of the era. In this situation, yards that included a well, toilet, barn, and an oven actually functioned as an opened-up hall. The houses that were disliked by Western visitors because of the selection of materials, temporary nature and lack of comfort actually overlaps with the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries Crusade spirit, and is in agreement with the analytic and resolute geometric language of the monumental architecture of the era.

Appendix 1: The number of Civil Architectural units outlined in Endowment Deeds and their shares in the all structures

We have counted the number of civil architectural unites outlined in Fatih Endowment Deeds and in Istanbul Endowment Survey Register (IESR) and compared them in respect to the all structures. There are certain unites whose exact numbers are not given in the endowment deeds and particularly in IESR but called as multiple. We take them as two in order to include them into our analysis as the term multiple means at least two. Another caveat may be related to miscalculations of the number of cells and shops in IESR. In fact, as we mention in the article, cells, unlike the units in residential places, are structures built in great numbers in endowed facilities and they are lodging places generally rented and used for social purposes. They are not homogenously distributed in cities. Therefore, the exclusion of cells and shops would make the comparison more straightforward and sound as the civil architecture meant to be free from public interference and institutions.

|

beyt-i süfli |

gurfe |

hücre |

menzil |

müstakil beyt |

beyt-i ulvi |

|

845 |

270 |

212 |

159 |

105 |

100 |

|

müstakil menzil |

mahzen-bodrum |

dükkan |

muhavvata |

çardak |

bağçe |

|

55 |

42 |

40 |

11 |

7 |

7 |

|

beyt |

sakıfsız beytler |

arsa |

fırın |

||

|

5 |

5 |

3 |

2 |

|

beyt-i süfli |

gurfe |

hücre |

beyt-i ulvi |

|

988 |

270 |

212 |

117 |

|

total menzil |

|

457 |

|

höcre |

hane-i tahtânî |

dükkan |

muhavvata |

kenif |

hane-i fevkânî |

|

4604 |

2271 |

1382 |

1344 |

1248 |

1147 |

|

höc.u veya f |

höc.s veya t |

bi'r-i ma |

ahur |

gurfe |

zulle |

|

758 |

750 |

654 |

481 |

475 |

472 |

|

furun |

hane |

sofa |

bağçe |

hane-i süfli |

oda |

|

414 |

414 |

342 |

268 |

218 |

185 |

|

cüneyne |

mahzen |

tahtânî ev |

hane-i ulvî |

matbah |

ev |

|

158 |

108 |

97 |

87 |

71 |

35 |

|

fevkanî ev |

beyt-i süfli |

zir-i zemin |

zemin-i maktu |

eşcar-ı müsmire |

kilar |

|

59 |

46 |

40 |

33 |

31 |

30 |

|

bodrum |

hamam |

beyt |

muhavvata-ı yesire |

serdab |

anbar |

|

28 |

27 |

27 |

21 |

20 |

19 |

|

kasr |

çardak |

arz-ı haliye |

asiyab |

beyt-i ulvi |

menzil |

|

16 |

15 |

13 |

12 |

11 |

11 |

|

asiyab-ı feres |

kerm |

selamlık |

mahtaba |

asiyab-ı ester |

mahba |

|

11 |

10 |

9 |

8 |

7 |

6 |

|

sikaye |

su küpü |

hayat |

dehliz |

sundurma |

şehnişin |

|

3 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

|

höcre |

hane-i tahtânî |

hane-i fevkânî |

höc.u veya f |

höc.s veya t |

gurfe |

|

4604 |

2271 |

1147 |

758 |

750 |

475 |

|

zulle |

hane |

sofa |

hane-i süfli |

oda |

tahtânî ev |

|

472 |

414 |

342 |

218 |

185 |

97 |

|

hane-i ulvî |

ev |

fevkanî ev |

beyt-i süfli |

beyt |

serdab |

|

87 |

35 |

59 |

46 |

27 |

20 |

|

kasr |

beyt-i ulvi |

menzil |

selamlık |

hayat |

şehnişin |

|

16 |

11 |

11 |

9 |

2 |

1 |

|

höcre |

hane-i tahtânî |

hane-i fevkânî |

gurfe |

zulle |

sofa |

|

6297 |

2958 |

1465 |

475 |

472 |

342 |

|

serdab |

kasr |

selamlık |

hayat |

şehnişin |

|

|

20 |

16 |

9 |

2 |

1 |

|

total menzil |

|

2431 |

FOOTNOTES

1 In the rest of the artice the phrase Ottoman-Turkish House will be used to indicate solely the known tradition without getting into an academic discussion.

2 Latîfî, Evsâf-ı İstanbul, prepared by Nermin Suner [Beijing], Istanbul: İstanbul Fetih Cemiyeti, 1977.

3 M. Baha Tanman, “Boğaziçi’nde Yalı Mimarlığının Gelişimine İlişkin Bir Deneme”, Sadullah Paşa ve Yalısı, ed. Deniz Mazlum, Istanbul: Yapı-Endüstri Merkezi, 2008, pp. 9-16.

4 Cyril Mango, “Approaches to Byzantine Architecture”, Muqarnas, no. 8 (1991), p. 41.

5 ibid. p.41.

6 Anthony Kriesis, “Über den Wohnhaustyp des Frühen Konstantinopel”, BZ, no. 53 (1960), p. 322.

7 ibid, p. 322.

8 Catherine Saliou, “Material Culture and Well-Being in Byzantium (400-1453)”, The Byzantine House (400-912): Rules and Representations, ed. M. Grünbart et.al., Wien: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 2007, pp. 199-206.

9 Paul Magdalino, “Medieval Constantinople: Built Environment and Urban Development”, The Economic History of Byzantium: From the Seventh Through the Fifteenth Century, ed. Angeliki E. Laiou et.al., vol. III, Washington: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection 2002, p. 534.

10 Ken Dark, “Houses, Streets and Shops in Byzantine Constantinople from the Fifth to the Twelfth Centuries”, Journal of Medieval History, no. 30 (2004), pp. 83-107.

11 Costas N. Constantinides, Byzantine Gardens and Horticulture in the Late Byzantine Period, 1204–1453, Washington: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2002, p. 87.

12 Ruy Gonzales de Clavijo, Anadolu, Orta Asya ve Timur: Timur Nezdine Gönderilen İspanyol Sefiri Clavijo’nun Seyahat ve Sefaret İzlenimleri, tr. Ömer Rıza Doğrul, compiled by Kamil Doruk, Istanbul: Ses Yayınları, 1993, p. 55.

13 Ekrem Hakkı Ayverdi, Fâtih Devri Sonlarında İstanbul Mahalleleri, Şehrin İskânı ve Nüfusu, Ankara: Vakıflar Umum Müdürlüğü, 1958, p. 71.

14 Mistra is the city which acted as the center for the Peloponnesian Despot, and the city to which he was exiled and from which Paleologos’ reigned.

15 Ayda Arel, Osmanlı Konut Geleneğinde Tarihsel Sorunlar, İzmir: Ege Üniversitesi Güzel Sanatlar Fakültesi, 1982, p. 68.

16 Lefteris Sigalos, Byzantine Constantinople: Monuments, Topography and Everyday Life, Leiden: Brill, 2001, p. 66

17 David Jacoby, “Houses and Urban Layout in the Venetian Quarter of Constantinople: Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries”, Byzantina Mediterranea, ed. Klaus Belke et.al., Wien: Böhlau, 2007, p. 269.

18 Arel, Osmanlı Konut Geleneğinde Tarihsel Sorunlar. p. 44.

19 For further information and visual material, see: Önder Küçükerman, Kendi Mekânının Arayışı İçinde Türk Evi: Turkish House in Search of Spatial Identity, Istanbul: Türkiye Turing ve Otomobil Kurumu , 1988.

20 Emel Esin, “Sadullah Paşa Yalısı”, Sadullah Paşa ve Yalısı, ed. Deniz Mazlum, Istanbul: Yapı-Endüstri Merkezi, 2008, p. 20.

21 For more information and visual material, Ayda Arel, “Cihannüma Kasrı ve Erken Osmanlı Saraylarında Kule Yapıları”, Prof. Doğan Kuban’a Armağan, ed. Zeynep Ahunbay et.al., İstanbul: Eren Yayıncılık, 1996.

22 Halil İnalcık, Donald Quataert (editor), Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’nun Ekonomik ve Sosyal Tarihi, tr. Halil Berktay, Istanbul: Eren Yayıncılık, 2000, p. 54.

23 ibid. p. 54.

24 Fatih Mehmet II Vakfiyeleri, Ankara: Vakıflar Umum Müdürlüğü Neşriyatı, 1938.

25 Ömer Lutfi Barkan, Ekrem Hakkı Ayverdi (eds.), İstanbul Vakıfları Tahrir Defteri 953 (1546) Tarihli, Istanbul: İstanbul Fetih Cemiyeti İstanbul Enstitüsü, 1970.

26 For more inforamtion, see: Emre Can Yılmaz, “İstanbul'da Yazılı ve Görsel Kaynaklara Göre 15. ve 16.yy’da (1453–1559) Osmanlı Sivil Mimarlığı Üzerine Bir Değerlendirme: Gurfe Örneği”, postgraduate thesis, Istanbul Technical University, 2009.

27 A menzil was a property in which everything was included (donated all together). In FV and İVTD the term menzil functions in this way.

28 Muhavvat(a) (from the Arabic havt’) means something that is encircled, curtained off or surrounded by a wall (see: Ferit Devellioğlu, Osmanlıca-Türkçe Ansiklopedik Lûgat, Ankara: Aydın Kitabevi, 1999. From here on, this will be shortened to DE). Divarlu yer, havlı (Câfer Çelebi, Risâle-i Mi‘mâriyye, prepared by İ. Aydın Yüksel, Istanbul: İstanbul Fetih Cemiyeti, 2005- from here, this will be referred to as RM).

29 Hans Dernschwam, İstanbul ve Anadolu'ya Seyahat Günlüğü, tr. Yaşar Önen, Ankara: Kültür Bakanlığı, 1992, p. 102.

30 Tülay Reyhanlı, İngiliz Gezginlerine Göre XVI. Yüzyılda İstanbul’da Hayat, Ankara: Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı, 1993, p. 41.

31 Salomon Schweigger, Sultanlar Kentine Yolculuk: 1578-1581, tr. Türkis Noyan, Istanbul: Kitap Yayınevi, 2004, p. 121.

32 Istanbul Metropolitan City Council Atatürk Library, Muallim Cevdet, Orta Yazma, no. 64; this Arabic register has not been published, however, Aygül Ağır’s (“İstanbul’un Eski ‘Venedik Ticaret Kolonisi’nin ‘Osmanlı Ticaret Bölgesi’ne Dönüşümü”, postgraduate thesis, Istanbul Technical University, 2001) research translated and used parts of this. The data in this study have been translated from this section.

33 Philippe du Fresne, Fresne-Canaye Seyahatnamesi 1573, tr. Teoman Tunçdoğan, Istanbul: Kitap Yayınevi, 2009, p. 47.

34 Numbers 40, 66, 132, 92, 132, 173, 125, 2494, 1037, 395, 501, 518, 537, 379…and more menzils.

35 Schweigger’s drawing “Istanbul Houses”, Lorichs’ “Details of a Structure near Çemberlitaş”, details of the Rumeli Feneri from Freshfield folio and other visual sources from the period demonstrate a common feature of half-timbered housing. For the visual materials, see: Salomon Schweigger, Sultanlar Kentine Yolculuk: 1578-1581; Melchior Lorck, Drawings from the Evelyn Collection at Stonor Park England and from the Department of Prints and Drawings, the Royal Museum of Fine Arts, prepared by Erik Fisher, Copenhagen: A. W. Henningsen, 1962; Wolfgang Müller-Wiener, Bizans’tan Osmanlı’ya İstanbul Limanı, tr. Erol Özbek, Istanbul: Türkiye Ekonomik ve Toplumsal Tarih Vakfı, 1998;

36 Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq, The Turkish Letters of Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq, Imperial Ambassador at Constantinople, 1554-1562, Oxford: Clarendon P., 1968, p. 24.

37 Reyhanlı, İngiliz Gezginlerine Göre XVI. Yüzyılda İstanbul’da Hayat, p. 40.

38 Pierre Gyllius, İstanbul'un Tarihi Eserleri, tr. Erendiz Özbayoğlu, Istanbul: Eren Yayıncılık, 1997.

39 Du Fresne, Fresne-Canaye Seyahatnamesi, p. 64.

40 Dernschwam, İstanbul ve Anadolu'ya Seyahat Günlüğü. p. 100.

41 On this matter, it is stated in a record (see: Ahmet Refik Altınay, On Altıncı Asırda İstanbul Hayatı: 1553–1591, Istanbul: Enderun Kitabevi, 1988, p. 58.) “…hususan Yehud tayifesi tabakatla âli evler ve çartakları ihdas eyliyüb…” thus relating the multistoried houses to the Jewish population.

42 Two examples that are compared in İVTD (439 and 1826 vakfiyes) support this claim. In the section of these vakfiyes unit, in the “asl- vakıf” section the structures that are referred to as gurfe, are indicated as fevkani in the “şart-ı vakıf” section, which relates how the buildings are evaluated. Those, it is natural that the term gurfe is used as a synonym for the fevkanîs

43 The depiction of housing in the water canal map drawn up by Üsküdar İbrahim Pasha in 1753 and Francesco Giovanni Rossini’s 1741 Istanbul depiction support one another in details of buildings. For the visual material, see: Kazım Çeçen, İstanbul'un Vakıf Sularından Üsküdar Suları, Istanbul: İstanbul Su-Kanalizasyon İdaresi, 1991 and Giovanni Curatola, Eredita Dell’islam: Arte Islamica in Italia:[mostra, Venezia, Palazzo Ducale, 30 Ottobre 1993-30 Aprile 1994], Milan: Silvana, 1993.