When writing a history of Istanbul, particularly in the Ottoman era, the historical context of the city must not be ignored. To understand the historical context, both the general political and socio-economic conditions of the empire should be taken into account and cities that are similar on a regional and global scale should be examined from a comparative perspective. Even though existing studies about Ottoman Istanbul take such historical contexts into consideration, they neglect to do so from a broader perspective.

is the aim of this article is not to narrate the history of Istanbul. Rather, I will address the city’s place on the world scale from a comparative perspective, taking the history of other cities into account. I will first establish the central position Istanbul holds within the historical process itself and then will attempt to exhibit the city’s position in comparison to other world cities by making comparisons between Ottoman Istanbul and major cities both within and outside the Ottoman Empire. The period I am examining - from the fifteenth to the nineteenth centuries - is quite long; however, this was an era in which many important transformations took place in urban areas throughout the world, and as a result it seems appropriate to make a dual periodization. The first period falls between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, a time in which Istanbul was the world’s most populous city and enjoyed profound global influence. The second period encompasses the years following the nineteeth century, when Atlantic trade and the Industrial Revolution began to have a great impact on the world.

ISTANBUL: EMPIRES AND CITY

Recent archeological excavations at Yenikapı have taken Istanbul’s known history back to around 8500 BC, but most in-depth historical accounts of the city begin in the seventh century BC. The history of Istanbul/Constantinople as a global influence, however, begins with the Byzantine period ushered in by Constantine the Great in the fourth century; the city flourished in the fifth century and developed into one of the most important cities on earth in the sixth century.1 During this period Constantinople not only claimed the inheritance of a pivotal Roman city, but also became a world city by becoming a critical hub for theological and institutional Christianity. The establishment of a commercial and political network that connected Constantinople with other cities of the world reinforced its international influence.

At a time when it was the center of Greek, Persian and Hellenistic cities, Rome played a central role; it was able to organize the scattered political nature of the region and reach all the ancient cities. Rome thus became a symbol of the Roman Empire and its most powerful manifestation. Rome was the most important actor of the Pax Romana period, which continued up until the second century AD. The quadruple governmental structure that emerged after Rome - which had maintained pagan culture against the spread of Christianity - lost its political integrity at the beginning of the third century and eventually led to the advent of a new Rome. This New Rome (Constantinople), where Christianity had attained legitimacy, became an important axis of the world, in part due its geographic location at the heart of the Roman Empire and its proximity to the centers of other civilizations. In his 1634 travel book, A Voyage into the Levant, Henry Blount captures the common notion that “with respect to power, abundance, and convenience, there is no equal to Istanbul. Istanbul stands almost in the middle of the world. From there, it can rule over many countries.”2 Because of its location, Constantinople/Istanbul was able to establish political, religious, cultural and commercial ties with the regions around it and surpassed Rome in becoming the most important city of the world. The development of Constantinople thus ushered in new eras for both the Roman Empire and Christianity.

As a result of both the emergence of Islam and its rapid spread, and also due to internal conflicts in Istanbul, Muslim dynasties secured dominance over Byzantium in the Eastern-Mediterranean a few centuries later. In the ensuing years, Constantinople’s connection to the greater Mediterranean weakened, resulting in a decrease in the city’s importance. In this period, cities that had political significance and were under the dominance of Muslim states became more influential. Baghdad and Damascus, in particular, were regionally influential due to their political, military, cultural and commercial power. It seems, however, that after a few centuries Constantinople re-strengthened its ties with the Balkans and the Mediterranean as a result of the role played by the Italian city-states and political instability in the Muslim world. Consequently, in the period stretching from the ninth century until the Latin invasion in 1204, Constantinople regained much of its previous significance.

We can, however, conceive of Constantinople during the 200-year period after it was relieved from Latin rule as a city that was historically important but drifting away from other central cities. By 1450, Constantinople found itself surrounded on all four sides by the Ottomans; it was able to maintain its existence only due to the strong walls that protected its population, which was between 40,000 and 50,000. Certainly, a population of 50,000 people was not a small number for the era (particularly in comparison to the much smaller populations of cities like Edirne and Bursa, which had yet to undergo substantial growth). Yet when we compare this figure to the population of Constantinople in either the sixth, tenth or eleventh centuries (in the hundreds of thousands) and its concomitant network of geographical and economic influence, it becomes obvious that Constantinople was well below its capacity.

The city continued to be relatively small and weak for a while after its conquest by the Ottomans. However, this time the city’s ascent towards becoming one of the most important urban centers did not take hundreds of years, but occurred in only half a century. Construction work and development of the city began immediately after the Ottoman conquest, which enlivened the city with new populations. The formation of economic networks linking the Mediterranean, the Balkans, and the Black Sea with Istanbul as their nexus occurred in a very short period, helping to ensure the peace and security of the city. In addition, the decision to make Istanbul the capital transformed it into a central world city.3 Owing to major construction projects that were carried out in the 1500s and the arrival of the sacred Islamic relics to the city, which had been newly declared as the home of the caliphate, Istanbul became a leading symbolic center for Islam as it had been for Christianity before. Turkish-Persian and Islamic traditions, and perhaps more tangibly, the office of the Caliphate and the magnificent mosques and complexes began to leave their mark on the city. In the wake of the fractured political situation that followed the Mongol invasions, the conquest of Constantinople by Sultan Mehmed II and the sultan’s determination to make it the capital created an opportunity for Muslim society to regain its strength. On the other hand, the sultan allowed the Byzantine heritage of the city to live on, despite the damage inflicted by the Latin invasion. The willingness of the Ottomans, and therefore Istanbul, to allow Islam to live side by side with Christianity and Roman traditions, was manifested in the form of the Patriarchate and great churches and monasteries, thus helping the city to increase its prestige and influence around the world. Moreover, the arrival of Jews from Spain and various other parts of Europe in Istanbul in the fifteenth century added a similar religious representation thus increasing the fame of the city. In time, Istanbul also came to occupy a special position for other ethnic groups, particularly the Armenians; Istanbul slowly began to gain a central role in bringing many of these religious and ethnic populations together. In a way, Istanbul became a capital city that encompassed the heritage of the ancient world. In fact, the emergence of the Pax Ottomana during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries only became possible due to the city’s newfound cosmopolitanism.

In addition to these political, symbolic, and social factors, the reestablishment of economic networks in the Mediterranean and Black Sea regions, as well as in the Balkans, supported Istanbul’s growing significance and potential. As Mehmet Genç states, the Black Sea was now entirely under Ottoman control and Istanbul’s economic integration could be achieved in a more comprehensive form than it had been in the Byzantine period.4 Both Muslim and non-Muslim merchants from various nations (in particular, Levantines residing in the Galata district), to whom guarantees of life and property had been given during the conquest, benefited from and diversified these economic networks, thus helping Istanbul to grow.5

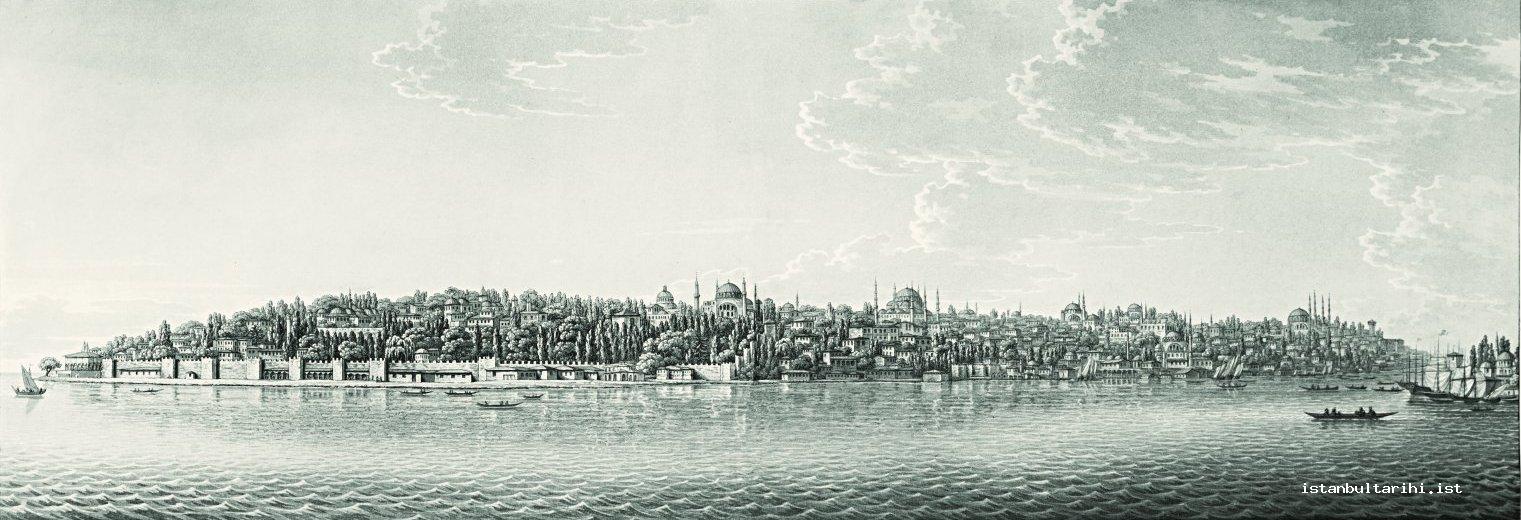

Consequently, merely a century after the city’s conquest, in the mid-sixteenth century Istanbul could count itself as one of the most populated cities in the world; indeed, it now had the political influence to match its great size. The city grew to become the most magnificent city in the region, a region that today we refer to as Europe, Anatolia, Middle East and the Mediterranean. With its institutions and structures, including palaces, madrasas, dervish lodges and convents, in addition to a great number of large kulliyes (complexes) and market places, and by setting aside some internal conflicts, Istanbul maintained its standing as one of the central cities of the Ottoman State, and indeed the world until the 1650s. Such great investments and improvements continued until the period of sultans like Mehmed IV, Süleyman II, Ahmed II and Mustafa II, who preferred Edirne to Istanbul. There are multiple reasons behind their preference. Not only did these sultans sustain an interest in hunting that was more readily satisfied in Edirne, but after the murder of Osman II, there was a conflict between the sultanate and the bureaucratic forces. Additionally, many of the long military expeditions of this era used Edirne’s open fields as their starting points.

The 1650s ushered in a period of change for Istanbul and other great cities alike. For example, the Russian ruler Peter the Great established Saint Petersburg and made it the capital city of his country (1703). Likewise, the French king Louis XIV moved the capital from Paris to Versailles (1686). During this period the central cities that were involved in Atlantic trade, which emerged after the discovery of America, such as Amsterdam, Antwerp and London, started to usurp the position of the main actors in Mediterranean trade such as Aleppo, Alexandria, Istanbul, Venice and Genoa. For example, Amsterdam experienced its golden age in the seventeenth century, with a population increase from 50,000 to 200,000. Similar extreme population increases were observed in many European countries of the period.6

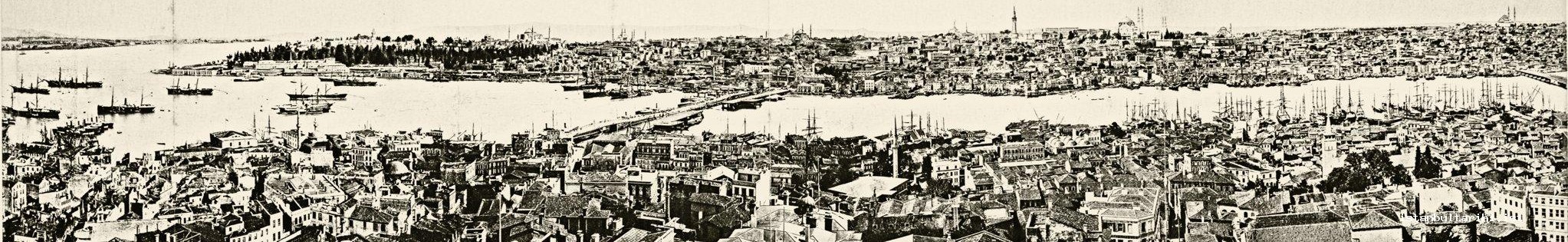

Istanbul, however, did not undergo a process of great change in this period. The city was perhaps recovering from the turbulence that had occurred between the 1650s and the 1710s, and was only to truly return to its earlier magnificence during “an interim period”, known as the Tulip Era (1718-1730), when new public spaces and activities were introduced. The city developed and expanded into areas outside the city walls and consistently maintained its population and influence against the rapid rise of European cities in the same period. The new world, centered round the Atlantic, America, and Europe, left Istanbul behind as the center of the old world in respect to both population and influence. During this process, Istanbul neither shrank nor deteriorated; however, in comparison to the rapidly growing cities of Europe, it became perceived as a static and archaic city, particularly in the nineteenth century. We can therefore interpret many of the regulations that had been put in place by the municipality and city in the nineteenth century as attempts to counter this perception, with the ultimate goal of stimulating growth in Istanbul to match its European counterparts.

It is necessary to reexamine Istanbul, particularly in the period after 1730, in comparison to cities within the Ottoman State and cities in other geographies; the causes behind the rapid growth of the European cities also started to have an influence on certain Ottoman cities during this time, in particular, Aleppo, Adana, Izmir and Thessaloniki. In addition to cities in the hinterland, many port cities along the coasts of both the Aegean and Mediterranean seas began to undergo transformations that were brought about by the establishment of new trade networks or the new opportunities that had been created. Mediterranean trade networks attempted to integrate themselves with the booming Atlantic trade network, which meant that the port cities had a special role to play. Istanbul was a port city, but the strict administrative and commercial import and export rules distinguished it from other port cities; this was also in part due to its status as the capital city.

In summary, the status of Istanbul as a central city changed throughout its long history. Istanbul fluctuated between being one of the truly central cities of the world, ad being more withdrawn and self-enclosed. However, even when it was in an introverted state, it was always a large city enclosed by equally great walls. The epithets that have been attributed to Istanbul over the course of its 1,600 years as a capital city offer a trans-historical perspective of its glory, whether they be “the Queen of cities”, during the Byzantine period, or the Belde-i Tayyibe (beautiful city) during the Ottoman period.

A few main elements come to mind when considering what led to Istanbul’s global status. We should first consider the aptitude of Istanbul’s sequence of political administrations. Throughout its history, great and powerful administrations led the city in its development towards attaining global importance. This becomes abundantly clear when we consider the Roman-Byzantine empires and their emperors in the fifth, sixth and tenth to eleventh centuries, as well as the Ottoman State and its sultans in the fifteenth to seventeenth centuries, times when the city was in a central position. The opportunity to expand the economic and socio-intellectual networks of these empires required the development of Istanbul alongside important world cities. Istanbul was one of the world’s most important cities during those periods in which it could increase and strengthen its ties and connections with the Mediterranean, the Black Sea and the Balkans. In this respect these historical periods were eras in which Istanbul had the widest networks and therefore reflected a great variety of ethnic, religious, intellectual and economic aspects in its structures. The new conditions created by the New World, Atlantic trade and the European Enlightenment affected Istanbul as well as other cities that were dependent on the Mediterranean-Black Sea network.7 The period of time from the nineteenth century to the present-day, a period in which these changes can be clearly observed, is a revealing window into how cities like Istanbul strove to adapt to this new situation.

ISTANBUL AND WORLD CITIES

In the previous section, we dealt with Istanbul’s geo-strategic position in relation to its growth and how its relationship with other world cities developed over varying historical periods. The evidence used to establish these historical processes were mostly based on literary and historical records. We positioned the city in relation to the world by examining its own internal and external relationships. Now it is necessary to examine this position comparatively within the framework of other cities by elaborating on it and making it more concrete. We selected different cities from Ottoman and other geographies, andour comparison is based on three criteria. The first criterion is the characteristics of the city’s topography and settlements; in other words, we need to examine the cities’ geographical location, topographic features and internal formation. Secondly, it is necessary to examine demographic and population statistics, as well as the ethnic and religious diversity of the relevant city. Lastly, it is necessary to look at architectural development and aesthetic values of each city. It should be noted here that the statistical data mentioned here, i.e. the size of the areas of the cities and their total population, is not exact information, but rather based on estimates gathered from various sources. Special attention has been paid to ensuring that population estimates are as reliable as possible, given the great variety of information available in first-hand sources.

The Ottoman cities we have examined in our comparative study are Bursa, Edirne, Sofia, Thessaloniki, Aleppo, Damascus, Cairo and Baghdad; the period is between the fıfteenth and seventeenth centuries. For the period between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, we have added the port cities of Alexandria and İzmir to this list. Generally, if we classify Ottoman cities in comparison to Istanbul, one group includes cities with populations of more than 80,000 to 100,000, while another consists of cities with populations between 15,000 and 80,000; the last group includes cities with populations smaller than 15,000. Of course, population size is only one criterion with which cities can be classified. The political-strategic positions of the cities (whether they are capitals, centers of provinces or smaller regions, logistic centers for military expeditions or cities which the princes lived, etc.), their positions in regards to commerce (cities with customs, port cities, cities on trade routes, centers in which raw materials were produced, etc.), and their positions in regards to architectural, artistic, and cultural frameworks remain very important in any comparative approach. Working within these frameworks, it is important to remember that Istanbul often acted as an exemplar for other cities in the region.

Cities like Venice, Vienna, Isfahan, Agra, Beijing, Saint Petersburg, Lisbon, Amsterdam, London and Paris are represented in the category of world cities. The first six on this list are cities that held central positions in the classical world or early modern period, while the others are cities that held central positions in the industrialization process and modern era. However, such a clear cut dual periodization does not apply to Istanbul – at least in consideration of such criteria as population, trade volume, architectural investments and intellectual developments. On a worldwide scale, but with special relevance to the major cities of Europe, the eighteenth century marked a period of great transition and transformation in many respects. Although the roots of these changes can be traced back to the fifteenth century, particularly in respect to artistic-aesthetic developments and the new commercial mindset formed by the discovery of the New World, the 1700s appear to be the critical turning point in terms of the results these developments had upon the major cities of the world.

Some of the most important features of Istanbul’s topography include the Bosphorus, the sheltered harbor of the Golden Horn, and the city’s great walls. The first two had vital significance in terms of both trade and in sustaining the city,but they also put the city at risk. However, because of its gigantic and heavily-fortified walls, Istanbul managed to save itself from this risk for hundreds of years. The walls of Istanbul were 22 kilometers long, and included 96 towers and 40 to 50 gates, making them among the strongest walls of the era and region. With respect to settlement opportunities, the 1,500-hectares of land within the city walls constituted a large area, not only for settlement, but also short-term sustenance by means of the many gardens and fields of the city. Moreover, by using the areas outside the city walls, Istanbul had the means to expand and establish connections towards Thrace on its western boundary, from Galata towards the Black Sea on its northern, and through Üsküdar towards Anatolia on the eastern border. After the Ottoman conquest, extensive pieces of land became available for cultivation and construction, including the neighborhoods now known as Eyüp, Sütlüce, Anadoluhisarı, Kadıköy, as well as large parcels north of Galata, stretching up to and including Sarıyer and Beykoz.

The aforementioned Ottoman cities were not comparable to Istanbul in such characteristics. For instance, it is recorded in various sources that the area enclosed by the city walls in Cairo, which was the Empire’s second largest city after Istanbul and which was known as Ümmü’d-dünya (mother of the world) or Mısr-ı Kahire, measured was only about 300 to 350 hectares in size. It is also stated that Aleppo, which entered under Ottoman control in 1516, had walls that measured five kilometers in length with only nine gates, contained about 350 hectares of land, making it more comparable to Cairo than Istanbul. The area within the city walls of Damascus, one of the Ottoman State’s major cities, was 128 hectares and the number of gates was seven. Cities towards the Western edge of the Ottoman State, such as Bursa, Edirne, Thessaloniki or Sofia, were much more modest in respect to the length of their walls and the size of their settlement areas; the total areas usually measured no more than 100 hectares.8

Many of the cities mentioned here, including Thessaloniki, Izmir, Aleppo, Damascus and Cairo, resembled Istanbul in that they were connected to the sea, either by being directly on the coast or in close proximity. Even though cities like Bursa and Sofia did not resemble Istanbul topographically speaking, in that they lacked direct connections to the sea and were located in mountainous areas, they remained connected and important to Istanbul due to their positions on key trade routes. In addition to the others mentioned above, there were other extremely strategic cities that had ports or commercial connection points. Cities like Edirne, Sofia and Thessaloniki connected Istanbul and therefore the Aegean and Black Seas to the Adriatic Sea. Because these cities were located on the historic Road of Egnatia, they had the opportunity to develop into central urban centers over time. Aleppo and Damascus enjoyed similar growth and fame due to being located on the Silk Road, which connected China and India to Istanbul; Cairo, meanwhile, benefitted from its location on the Spice Road. An important question comes to mind at this point: if these cities were like Istanbul in that they were important centers on trade routes that ran between distant lands, what factors led to differences in development?

We should first examine the differences in these cities from demographic and architectural/aesthetic aspects, and then return to this question. When their populations are compared, Ottoman cities can be categorized as those with a population of less than 15,000, those with a population between 15,000 and 80,000, and those with a population of more than 80,000. When they are examined from this perspective, taking the 1700s as a point of reference, cities like Sofia, Ankara and Erzurum, located on key trade networks and known as şehzade (prince) cities, and cities such as Manisa, Amasya and Trabzon can be included among those cities with less than 15,000 residents. Port cities like Thessalonica and İzmir and former Ottoman capitals like Bursa and Edirne had populations of more than 15,000 but less than 50,000 people. Cities with populations of more than 80,000 to 100,000 people included the major port city of Aleppo and cities like Damascus, Cairo and Baghdad, which had earlier served as the capital for dynasties like the Umayyads, Abbasids, Seljuks, Ayyubids, Fatimids, and Mamluks. Even though port cities experienced quick growth after the 1700s, there were not any cities in either Anatolia or Rumelia that had populations of more than 100,000. In this respect, Istanbul stood out.9

When population structures, including ethnic and religious affiliations, are examined, almost all the Ottoman cities prove to have been both religiously and ethnically diverse, although none match the heterogeneity of Istanbul. Along with main groups of Muslims, Greeks, Armenians, Jews and Gypsies, populations from other foreign lands, including a significant Catholic population, existed in Ottoman cities at varying rates.

From an architectural/aesthetic standpoint, important numbers of significant monuments existed in Ottoman cities other than Istanbul. Cities that already had a rich architectural heritage before the Ottomans, such as Cairo, Damascus or Aleppo, gained even richer architectural renown with the construction of Ottoman monuments. It appears that many monuments were constructed during the Ottoman era in cities that were in ruins at the time of the Ottoman conquest or in other small cities. For example, when we look at the geographical distribution of the works constructed by Chief Architect Sinan in the sixteenth century, it can be seen that the sultans, their wives and mothers, high ranking bureaucrats, and leading members of society joined in this process of making monuments. Istanbul, of course, was the city in which Koca Sinan did most of his work. However, he also constructed many monuments of differing quality and scope in cities like Sofia, Sarajevo, Bursa, Edirne, İzmir, Manisa, Erzurum, Ankara, Aleppo and Damascus. Even though the number of major architectural monuments that were constructed decreased between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries, the building of smaller size külliyes (complexes), private libraries, fountains, and residential areas continued. The situation was no different in the other cities. Large projects, including külliyes and imarets (soup kitchens), which required major financial support, were not commonly constructed in cities other than Istanbul, but some did exist. Cities like Bursa, Edirne, Manisa and Damascus are among those that included large kulliyes. The kulliyes commonly comprised of structures like mosques, madrasas, and bathhouses.10

Throughout its history, Istanbul was the largest Ottoman city in respect to population. Apart from a few cities, it was at least ten times larger than other Ottoman cities. Additionally, Istanbul had a very diverse population (about half or just over half of its population was Muslim, while the rest was made up of diverse religious and ethnic groups), comparable to other Ottoman cities at the time. Generally, the ratio of Muslim to non-Muslim populations was in favor of the latter in the Balkan and Aegean regions, but in favor of the former in Anatolian areas. By the end of the nineteenth century, this ratio appears to have been fairly balanced in Istanbul.

With respect to architecture, The construction of places of worship, marketplaces, and other public buildings were commissioned and sponsored these cities by sultans, high-ranking bureaucrats, and prominent members of society in accordance with the Ottoman tradition of establishing cities and urbanization. In regards to size and quantity, however, none of the cities could rival the level of structures found in Istanbul. The only exceptions were, as mentioned before, the earlier Ottoman capitals of Bursa and Edirne, as well as cities like Damascus, Cairo and Baghdad. Nevertheless, even these cities did not have characteristics that could compete with Istanbul.11

In the early modern period, the situation for European cities was fairly similar to what has been described above. As the gate of Europe opened to the Atlantic, the city of Lisbon was one of the most important cities between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. This city was located on important distribution networks for products that were coming from the Far East, India and the Mediterranean. The city’s walls protected Lisbon’s population, which was about 65,000 in the 1520s, and 165,000 in the 1600s; the walls had 77 towers and 34 gates. Lisbon became an important city for geographical expeditions, particularly for the travels of Vasco da Gama, which eventually led to the discovery of the New World. Lisbon continued to be one of the most important cities of Europe until the seventeenth century, when it ceded its role to Amsterdam and London.12

Venice is another important city which enjoyed control of the Adriatic and Mediterranean trade before Lisbon tightened its grip on the region. Venetians were among the most important traders in Istanbul, especially during the Byzantine period, but they lost much of their influence in the Mediterranean as a result of their power struggles with the Ottomans. With the discovery of the Atlantic and the New World, Venice lost much of its power to the cities that were waiting to take advantage of this new Atlantic trade network. Throughout history, Venice maintained its significance; in the 1600s it had a population of about 150,000 and was an island city. Protected by the sea, Venice was similar to Istanbul in many ways, and the two cities were in close contact with each other between the tenth and fifteenth centuries, either via direct competition or through strategic partnerships. During this period, Venice was often ahead of Istanbul in terms of development and commerce.

A different major city, Vienna, was the fourth largest city in Europe at the beginning of the twentieth century, with a population of about 2,000,000; however, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the city was quite small in comparison to Istanbul. The population of Istanbul was between 50,000 and 100,000 in the eighteenth century, and 250,000 in the nineteenth century. Located on the Danube River, Vienna benefitted from the transport capabilities of the river and became a major center of Europe in the 1800s.

The world cities most comparable to Istanbul with respect to geography were those located on river banks or straits. The two most prominent examples from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were Agra (or Akbarabad) and Isfahan. Agra, which served as the government center for the Mughal emperors Akbar, Jahangir, and Shah Jahan in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, was founded on the banks of Yamuna River. Agra is famous for housing the Taj Mahal, one of the world’s most important architectural monuments; its 38-hectare castle has four gates. Agra continued to be an important trade center and influential city in the region until Delhi (Shahjahanabad) was declared the capital city at the end of the seventeenth century. Although Isfahan was the capital city of the Safavids from the 1500s to the 1720s, and further was an important aesthetic and trade center, Agra was twice as large as Isfahan in the 1630s. Nonetheless, it seems as if Istanbul was larger than both cities at the time. It is known that the populations of both Agra and Istanbul were greater than 500,000 in the 1650s, while the population of Isfahan was estimated to be between 300,000 and 500,000. Moreover, while Agra and Isfahan lost much of their political influence after the 1700s, Istanbul continued to rule as the capital city for centuries. Delhi replaced Agra, and Tehran replaced Isfahan during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries; these new cities became influential urban centers in their regions, comparable to Istanbul.

Without a doubt, the most important cities of the Far East in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were Beijing, the capital of the Chinese empire, and Kyoto, the capital of the Japanese empire. After Beijing was established as the capital, it became what was probably the world’s largest city with a population close to 1,000,000 in 1550. The area of the city was renowned for its size, and the land encompassed by its walls was 6,200 hectares in size, four times larger than that of Istanbul. As for its population, taking various estimates together (some researchers argue that Beijing had a population of 600,000 to 700,000), we can surmise that the population of Beijing and Istanbul were similar. On the other hand, the city of Kyoto was a major city in the region with a population of about 500,000 in the 1650s; the capital city was moved to Edo, i.e. Tokyo, in the eighteenth century. With a population of more than 1,000,000 between 1750 and 1800, Beijing became one of the most crowded and fastest growing cities in the world.

As for the western side of the world in the modern period, new cities emerged in the wake of New World expansion. Benefitting from the opportunities afforded by new trade routes and innovations in industry and finance, these cities began to usurp classical cities in and around the continent. Stockholm and Amsterdam are two primary examples of such cities. In the period between 1600s to the late eighteenth century, Amsterdam experienced unprecedented growth; for example, its population of 30,000 people in the 1600s reached 200,000 in the 1700s. It became a major nexus for Asian, African and American trade networks. However, in the 1700s many of its commercial strengths were transferred to London, in addition to its concomitant wealth. The population of London increased from around 75,000 at the beginning of the 1500s to 220,000 at the beginning of the 1600s; and from 450,000 in the 1650s to 1,000,000 in the early 1800s, eventually reaching 2,000,000 in the 1850s. In comparison to these cities, Istanbul enjoyed stable population growth rate during this period, i.e. from the 1650s to the 1850s.

It would not be an exaggeration to state that the city of London owed its substantial growth in this period to the skill of its bankers and financiers. After the Great Fire of 1666, London had the opportunity to rebuild itself, which prepared the city for substantial population growth. In 1910, the city had a population of 7 -8,000,000, but after the 1920s much of its power, population, and financial strength moved to New York. Meanwhile, Paris had a population of around 500,000 by the 1700s, which was less than the population of Istanbul. But Paris soon caught up to Istanbul, and by the 1800s it had a population of 600,000. After that date, Paris left Istanbul behind and it began the 1850s with a population of more than 1,000,000.13 Seventeenth century travelers, such as Thévenot and du Mont, compared the cities of Paris and Istanbul and claimed that Istanbul was twice as large as Paris.14

Other European cities, such as Dublin, Copenhagen, Edinburgh and Saint Petersburg were transformed into important cities in the period between the 1650s and the 1700s. Their transformations into major urban centers were due to aesthetic, artistic and intellectual shifts rather than rapid population growth or topographical characteristics. New outpourings of wealth in cities such as these helped to establish strong industrial and financial foundations, which in turn supported cultural investments and intellectual thought.

According to the results of this study, most of the cities examined (in both Ottoman and other geographies) resemble Istanbul in some form or another. They are situated on the banks of a strait or river; they share similar geo-strategic and political-symbolic positions, they have substantial city walls and areas within the walls, they were able to expand to areas outside the city walls for settlement purposes, they were situated on major trade networks, they had similar population sizes, they had ethnic or religious diversity, and they also had examples of monumental architecture. Istanbul, however, contained all these elements while other cities possessed only some.

Mehmed II’s decision to make Istanbul his capital city after conquering it was one of the most important steps for the city to expand its substantial advantages and capacity. Istanbul had already served as the capital city of the Byzantine Empire for more than 1,000 years and the decision to allow it to continue its function as a capital was an important one that would maximize the city’s potential. Thus, it was afforded the opportunity to establish networks with other cities within the context of its political position. The second element that supported this consisted of the conquests that were continued by Mehmed II and Bayezid II; this eventually ensured the security and control of the Mediterranean and Black Sea basins. In this way, Istanbul was also able to establish commercial and trade connections with other cities. The development and construction of the city that was immediately undertaken by the Ottomans upon conquest fed these political and commercial networks as well as intellectual and physical migration. In addition, the religious-sacred nature and symbolic values the city gained, not only with the Patriarch, and even more so as the center of the caliphate, meant that Istanbul gained world renown, distinguishing it from other cities and placing it among central cities with these unique features. In the same way that the city walls kept the Byzantine capital standing for so many years, they also kept Istanbul secure and peaceful until the final days of the Ottomans. Finally, although it was intended that Istanbul be transformed into a modern-nation state conjuncture via certain processes such as controlling it with municipality and provincial regulations (i.e. the centralization of all the activities of the city, planning the structure of the city and bureaucratizing the day to day functions), these processes belonged to a completely different world, and thus Istanbul fell outside of it. Following the demise of Ottoman Empire and the formation of the Turkish Republic, Istanbul ceded its position as the official capital to Ankara, and accordingly fell out of favor of government officials.

FOOTNOTES

1 See: Bahattin Öztuncay (ed.), Gün Işığında İstanbul’un 8000 Yılı: Marmaray, Metro, Sultanahmet Kazıları, Istanbul: Vehbi Koç Vakfı, 2007; Bizantion’dan İstanbul’a Bir Başkentin 8000 Yılı, Istanbul: Sabancı Üniversitesi Sakıp Sabancı Müzesi, 2010.

2 Gülgün Üçel-Aybet, Avrupalı Seyyahların Gözünden Osmanlı Dünyası ve İnsanları (1530-1699), Istanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 2003, p. 433.

3 Çiğdem Kafescioğlu, Constantinopolis/Istanbul: Cultural Encounter, Imperial Vision and the Construction of the Ottoman Capital, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2009.

4 Mehmet Genç, Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’nda Devlet ve Ekonomi, Istanbul: Ötüken Neşriyat, 2000, pp. 311-332; Mehmet Genç, “Klasik Osmanlı İktisadi Sisteminde İstanbul’un Yeri”, Kültürler Başkenti İstanbul, edited by Fahameddin Başar, Istanbul: Türk Kültürüne Hizmet Vakfı, 2010, pp. 224-231; in addition, see: Fernand Braudel, Akdeniz ve Akdeniz Dünyası, translated by Mehmet Ali Kılıçbay, II vol., Istanbul: Eren Yayıncılık, 1989-90.

5 Halil İnalcık, Essays in Ottoman History, Istanbul: Eren Yayıncılık, 1998, pp. 269-354.

6 Fernand Braudel, Maddi Uygarlık, Ekonomi ve Kapitalizm: XV-XVIII. Yüzyıllar: Dünyanın Zamanı, translated by Mehmet Ali Kılıçbay, Ankara: İmge Kitabevi Yayınları, 2004.

7 See, Peter Hall, Cities in Civilization: Culture, Innovation and Urban Order, London: Phoenix Giant, 1999.

8 For the characteristics of some city walls, see: David Nicolle, Saracen Strongholds 1100-1500: The Central and Eastern Islamic Lands, Oxford: Osprey, 2009.

9 Cem Behar (ed.), Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’nun ve Türkiye’nin Nüfusu: 1500-1927, Ankara: Başbakanlık Devlet İstatistik Enstitüsü, 1996.

10 Ekrem Hakkı Ayverdi, İ. Aydın Yüksel, İlk İki Yüz Elli Senenin Osmanlı Mimârisi, Istanbul: İstanbul Fethi Derneği, 1976; Ekrem Hakkı Ayverdi, Osmanlı Mi‘mârîsinde Fâtih Devri, Istanbul: İstanbul Fetih Cemiyeti, 1989; Ekrem Hakkı Ayverdi, Avrupa’da Osmanlı Mimârî Eserleri, vol. IV, Istanbul: İstanbul Fethi Derneği, 1977-82.

11 Aptullah Kuran, “A Spatial Study of Three Ottoman Captials: Bursa, Edirne, and Istanbul”, Muqarnas, 1996, vol. 13, pp. 114-130.

12 John Julius Norwich (ed.), The Great Cities, London: Thames & Hudson, 2009.

13 Peter Clark and Bernard Lepetit (ed.), Capital Cities and their Hinterlands in Early Modern Europe, Aldershot: Scolar Press, 1996.

14 Üçel-Aybet, Avrupalı Seyyahların Gözünden Osmanlı Dünyası, p. 436.