Many significant events occurred in Istanbul in 1806. The war that erupted against Russia that year removed Istanbul from the anti-French coalition led by Britain and Russia, and brought the city diplomatically closer to Paris. Following the arrival of General Sebastiani in the Ottoman capital as an ambassador, French influence noticeably increased in the Sublime Porte and the lands under its control. This activated political lobbies in London; they worried about French dominance over the Mediterranean. In fact, British ambassador to Istanbul Charles Arbuthnot attempted to end the Russo-Ottoman War and ensure the passage of ships flying the Russian flag through the Bosphorus; however, his efforts failed. On 3 September, 1806, the British ambassador requested a British fleet come to the Ottoman capital with the hope of using it to intimidate the Sublime Porte as well as to evacuate both himself and the British citizens living in Istanbul. This action transformed what was a problem into a crisis. Immediately responding to the call for help from Arbuthnot, London sent the first part of the requested fleet to Çanakkale at the end of November.

The British fleet, which initially included the two largest battleships of that period and two smaller ships, anchored off the Dardanelles. After a short while, a battleship in the service of the British Embassy in Istanbul would join these four ships. The second part of the fleet, which consisted of five battleships and two smaller ships, anchored off Bozcaada at the beginning of February 1807. After the British ambassador and British merchants left the Ottoman capital on 29 January, 1807, the fleet started to wait for the wind to change to make their attack.

The British fleet did not cut off diplomatic relations, maintaining contact with kaptan pasha Salih Pasha in Çanakkale; they hoped for time to solve the conflict peacefully. The fleet—consisting of twelve ships—lost one ship at this point; it burned and eventually exploded for unknown reasons. This incident worried commanding officer Admiral Duckworth regarding the course and consequences of the operation. The British fleet was not backed up by infantry forces and had lost the ability to totally control Istanbul. The main purpose of their action—referred to as an “operation” in British documents—was not to conquer Istanbul, but to intimidate the Sublime Porte and bring the Ottoman State back into the anti-French coalition.

Residents of Istanbul, who never felt under threat, had concerns similar to those of the fleet. The rumor that the British fleet would attack the Ottoman capital was making the rounds in Istanbul and authorities were making efforts to reinforce the city’s defenses. In case the British passed through the Dardanelles, the existing castles and the fortifications to be built in the Ottoman capital would be the second and final defense line.

French Ambassador Sebastiani—who was assisting the defense preparations in the Tersane (shipyards) and the Tophane (arsenal)—and legate of Spain Marki d’Alménara, France’s ally in Istanbul, examined the Bosphorus accompanied by Ottoman engineers to ascertain which castles and towers were in need of restoration and in which regions fortifications should be built. One of the suggestions made by foreign experts was to demolish the Maiden’s Tower—located on a junction point of the Bosphorus—in order to build a fortification in defense of Istanbul. Even though the Ottoman government objected to the destruction of this historic structure, it did agree to fortify the Maiden’s Tower as much as possible—this was done by building embrasures. The government also agreed to construct fortifications in place of a few old towers and mansions along the Bosphorus.

The wind the British fleet had been waiting for started up on 18 February, 1807; Admiral Duckworth ordered that the fleet set sail. Even though the British fleet—which consisted of eleven ships at that point—faced small-scale resistance on the following day, it passed through the Dardanelles Strait without any losses and sailed into the Marmara Sea.

Written notifications sent by kaptan paşa Salih Pasha, who had arrived in Istanbul before the fleet, escalated panic in the capital. At the same time, these notifications accelerated the efforts to fortify the Bosphorus. Fortifications of the site under İncili Pavilion were the first priority. The Baruthane (gunpowder factory) and Tophane were put into action to produce the necessary canons and ammunitions.

Leaving one of the ships of the fleet in Çanakkale for security reasons, Admiral Duckworth and his fleet of ten ships anchored off Kınalıada, a safe harbor, on 20 February, 1807. At this time, Istanbul had not yet been fully prepared for a battle. Now the Sublime Porte required time. Far from supply points, without military support, and trapped in a region surrounded by enemies, the British marines wanted to find a solution without fighting.

Hoping to end the hostilities, Arbuthnot demanded the renewal of the Ottoman-British alliance and suggested acting as negotiator to bring the ongoing battle between the Ottoman State and Russia to an end. The British ambassador also wanted St. Petersburg and Istanbul to sign the same alliance agreement during the post-war period. In these agreements, Arbuthnot made a promise on behalf of the British committee that the territorial integrity of the Ottoman State would be maintained and that no demeaning demands would be made of the Sublime Porte. As a result of these agreements, Arbuthnot also promised that in case of a French attack against Istanbul, the allies would respond in the severest way possible and assist the Ottoman State.

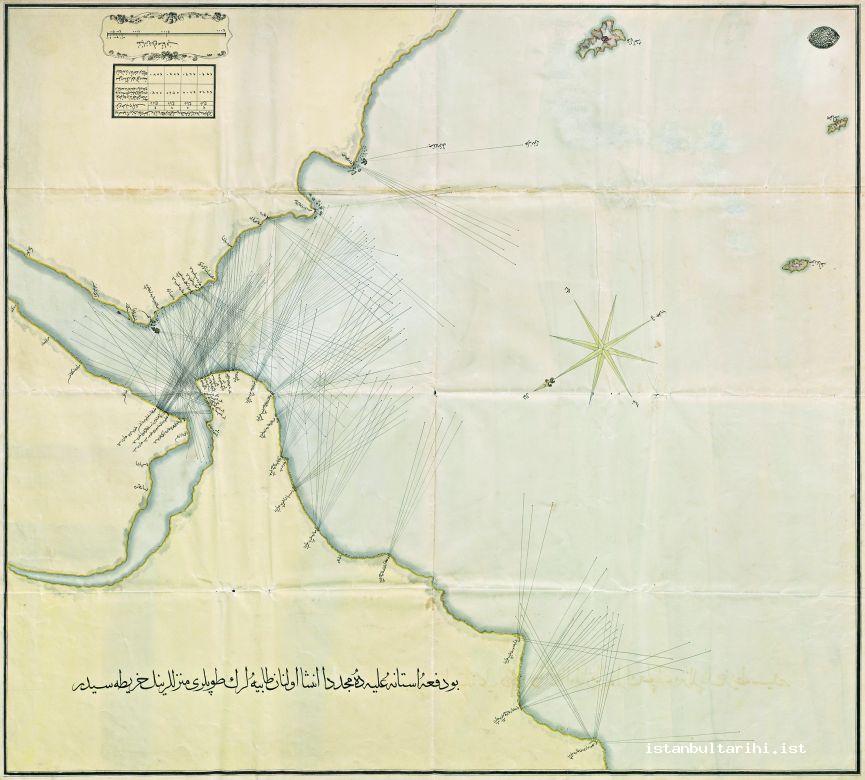

Considering the negotiations as an important way to save time, on the following day (21 February, 1807) the Sublime Porte sent Safiyesultanzade İshak Bey to the fleet. The Sublime Porte was trying to ensure the peaceful departure of the fleet from Istanbul while continuing war preparations. The Ottoman navy made rapid preparations for war and, in the framework of the defense plan prepared by Sebastiani, high-ranking government officials were assigned to the fortifications that were still being built along the Topkapı Palace coastline, Ahırkapı, Çatladıkapı, Kumkapı, Yenikapı, Davutpaşa Pier, Samatya Gate, Yedikule, Harem Pier, Kadıköy and Fenerbahçe.

Immediately after the arrival of Sebastiani in Istanbul on 22 February, 1807, the canoneers, and ammunition and military engineers who had been requested from Napoléon arrived in Istanbul. Their arrival greatly accelerated the construction of fortifications. The basic defense elements had been prepared to prevent the British fleet from approaching the city—or at least prevent it from taking a position on the Bosphorus from which it could bomb the city. Additionally, the Golden Horn was to be protected in order to prevent the British fleet from attacking the Ottoman navy anchored off the Istanbul harbor. Finally, support was to be provided to the Ottoman navy in case the fleet bombarded the city.

The residents of Istanbul also contributed greatly to the war preparations against the enemy who had now reached the capital. People were terrified by the arrival of the British fleet. In addition to working on the construction of fortifications, they also prepared for a potential battle with guns that had been distributed to them. Even the non-Muslim citizens, who normally were not included in the battles or war preparations, poured to the Bosphorus and supported the construction of bastions under the leadership of their religious leaders. The fact that people were able to mobilize in only a few days reflects the power of the rumors that were afloat in Istanbul.

The most important subject of the conversations in the coffeehouses—which were generally under the control of the Janissaries—was the rumor that the British would disembark and rape the girls and loot and destroy the shops. Some of Istanbul’s residents interpreted the British assault, which targeted the heart of Memâlik-i Mahruse (Ottoman territory), as a direct sign of doomsday and expected the Mahdi. This was undoubtedly one of the most important elements that mobilized the people. Another group of people believed that the British had been invited to Istanbul by the supporters of the Nizam-ı Cedid in order to abolish the Janissary corps. The fact that these kinds of rumors were being spread reflects not the power of the British fleet, but rather the psychology of the residents in the capital who felt themselves under threat for the first time.

Admiral Duckworth and British Ambassador Arubthnot, who were hobbled by the unfavorable winds and currents of the Bosphorus, had to be content with observing the ongoing construction of fortifications on the Bosphorus shore. İshak Bey and the interpreter of the imperial divan, Hançerlizade, managed to keep the admiral and the British ambassador busy. While the diplomatic contacts were continuing, the dinghies moving between the ships and the Princes’ Islands to get water were harassed by the dilavers (fighters) in the fortification units at Fenerbahçe.

The current military situation turned in favor of Istanbul’s residents when defense preparations were completed on 25 February, 1807. The Ottoman navy, anchored in the shipyard, consisted of twelve ships. They were prepared for war and only waited for the order to attack. With them were more than twenty artillery dinghies and over a hundred small boats. While the Golden Horn was blocked by double rows of dinghies, fire ships were located near Tophane in case of an attack there. The fortification units—which were rapidly completed thanks to the efforts of all of Istanbul’s residents—would be able to provide fire support for the Ottoman side if a battle ensued on the Bosphorus. In the preparations, which took about five days, a total of 361 fortifications were built along the Bosphorus; 77 were built in the region that stretched from Yedikule to Sarayburnu, 24 in the palace gardens, 127 in the region that stretched from the Golden Horn to Sarayburnu, 47 opposite this location, 38 along the Tophane coastline, and 48 on the Asian side. A total of 540 canons and 110 mortars were located in those fortifications.

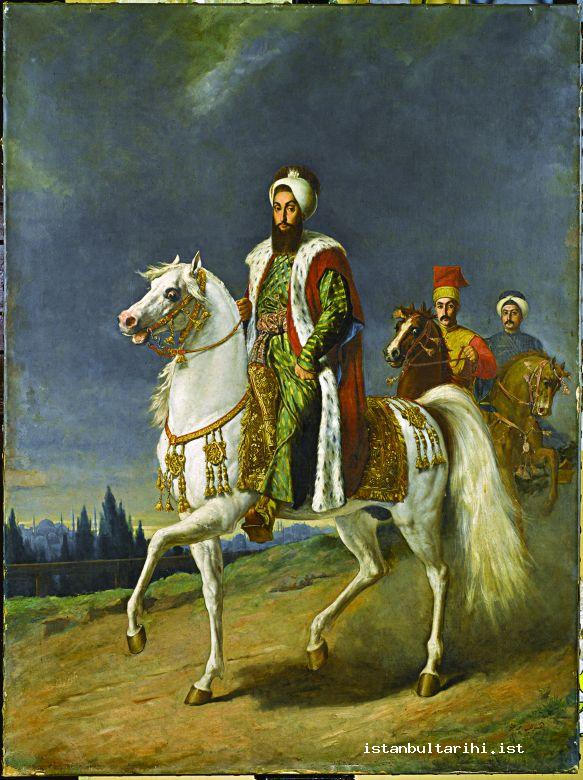

The British fleet was sent a quite strongly-worded note via Halet Efendi and, after the defense preparations had been completed, the negotiations with the British fleet were immediately terminated. In the meantime, a group of Ottoman soldiers landed on Kınalıada, the land nearest where the fleet was anchored. The existing tension had now escalated into a battle. The battle between the British marines and the Ottoman soldiers centered around the monastery, which was set back on the island. The support provided in this battle by local non-Muslims was vital in repelling the British marine corp. In fact, the non-Muslims who helped their fellow countrymen in the battle were later excused from paying the jizya. Selim III, who apparently felt helpless from the beginning to the end of the operation, was praying at the entrance of the Hırka-i Saadet, and shedding tears as he saw the supreme sacrifices the people were making in the capital.

The military success fortunately provided the Ottomans with a sense of psychological superiority. The British, on the other hand, could not help feeling inferior. As a result of that inferiority, and following the arrival of the marine corps at the ships, a decision was made by the British command committee to terminate the operation despite the objections of Admiral Sidney Smith. The British fleet, which was deployed on the morning of 1 March, 1807, set out on maneuvers from the Princes’ Islands and left the Ottoman capital on the same day. The fleet that reached the Dardanelles two days after this incident was severely damaged by the fortification units along the straits; these had been strengthened while the fleet was in Istanbul. The fleet then anchored off Bozcaada once again. The British, who left Istanbul after losing 46 soldiers and having 235 wounded, made contact with the Russian fleet under Admiral Seniavin’s command; the Russians had reached this location on 7 March, 1807.

Taking into consideration the Bosphorus fortifications and the attitude of Istanbul’s residents towards the enemy, Admiral Duckworth refused Admiral Seniavin’s offer to start a joint operation in Istanbul. He also stated that under the present circumstances attacking the Ottoman capital alone would amount to nothing. The war that broke out in 1807 between the Ottoman State and Britain, which was unable to attain any of the political or military goals it envisioned at the beginning of the operation, was officially brought to an end with the Kal’a-i Sultaniye (Treaty of the Dardanelles), which was signed in 1809.

The consequences of the operation to Istanbul and the Ottoman State are incredibly important. The difficulty in dispatching basic goods and merchandise to Istanbul during and after the attack caused an instant increase in prices in the Ottoman capital and the guns that the state had distributed to Istanbul’s residents could not be recollected. A rumor was also spreading that the fleet had been invited to Istanbul by the Nizam-ı Cedid supporters in an attempt to abolish the Janissaries. All these events made the situation in Istanbul very tense. The British operation had also changed the image of Selim III and the supporters of the Nizam-ı Cedid radically. Among the important details to be mentioned in this context, we can include the fact that Britain—a country that was allied with the Sublime Porte only a few years earlier—now threatened the capital of the Ottoman State. The army of the Nizam-ı Cedid, which had been organized due to the vulnerability that the Janissaries were accused of creating, was helpless against this threat. So for many Istanbul residents, Selim III and the Nizam-ı Cedid were now considered incapable of protecting the capital despite all the money and effort they had spent to do so. The opposition, under the leadership of craftsmen and Janissaries, spoke out against this lack of power; however, this was not taken into consideration by the palace or the Nizam-ı Cedid supporters. On the contrary, it was insisted that the agenda of Nizam-ı Cedid be pursued.

The rebellion that would dethrone Selim III and put an end to the Nizam-ı Cedid began three months after the British operation from the Bosphorus castles, which had been fortified against possible assaults in the future and where the soldiers had been compelled to enlist in the Nizam-ı Cedid army. So it’s clear that there’s a direct correlation between the British assault and the rebellion under the leadership of Kabakçı Mustafa.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

“Forcing the Dardanelles, Passages in the Life of a Sailor”, The United Service Journal and Naval and Military Magazine, 1842, vol. 14, (The memoirs of a young British officer who participated in the operation).

Rose, Holland, “Admiral Duckworth’s Failure at Constantinople in 1807”, The Indecisiveness of Modern War and Other Essays, London: G. Bell and sons, ltd., 1927, pp.157-179

The National Archives, Admiralty, 51/1642 (Journal of the Royal George, the flagship of the British fleet which came to Istanbul)

Yeşil, Fatih, “İstanbul Önlerinde Bir İngiliz Filosu: Uluslararası Bir Krizin Siyasî ve Askerî Anatomisi”, ed. S. Kenan, Nizâm-ı Kadîm’den Nizâm-ı Cedîd’e III. Selim ve Dönemi = Selim III and His Era, from Ancien Régime to New Order, Istanbul: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslam Araştırmaları Merkezi (İSAM), 2010, pp. 391-493.