Children’s and toy museums existing in many countries, cities and towns have paved the way for researchers to study the cultural history of the region they are located in. In Turkey there is some research tracing back to the origins of the country’s children’s and toy museums that illuminates the history in question. When it comes to Istanbul’s retro toymanship, there are 28 toys from stores in Eyüp, which are protected in Metropolitan Municipality Collections, that serve as important guides for the researchers.

Toy shops in Eyüp

In the Eyüp district of Istanbul, the imperial seat, toys have been produced and sold for hundreds of years. These toys were produced in the shops facing each other on the two sides of “Oyuncakçı Çıkmazı” (Toyman Blind) street opening to the Eyüp Sultan Mausoleum. While the name “toys of Eyüp” sounds like the concept is reduced to a specific place and evoking locality, it also defines traditional Turkish toymanship. In addition to being a production centre in that time, Eyüp was where toys were distributed to the rest of Istanbul and Anatolia via different mediums.

The very first toy was produced by Moulder (Dökmeci) Hasan Agha, who came to Istanbul as a Mansure soldier in the period of Mahmud II and played tabor in the inauguration of Rami Barracks (Rami Kışlası) in Eyüp. Having settled in Eyüp, Hasan Agha worked as a Ramadan drummer [responsible for waking the Muslims up and reciting different poems (mani) for suhoor (pre-dawn meal during the holy month of Ramadan)] and as a toyman, being called the “Spitting (Tükrüklü) Toyman.” Later, Goblet drummer (Darbukacı) Halil Efendi from Gümüssuyu and Küçük İsmail Efendi helped this art expand thanks to the toyshops they opened.1

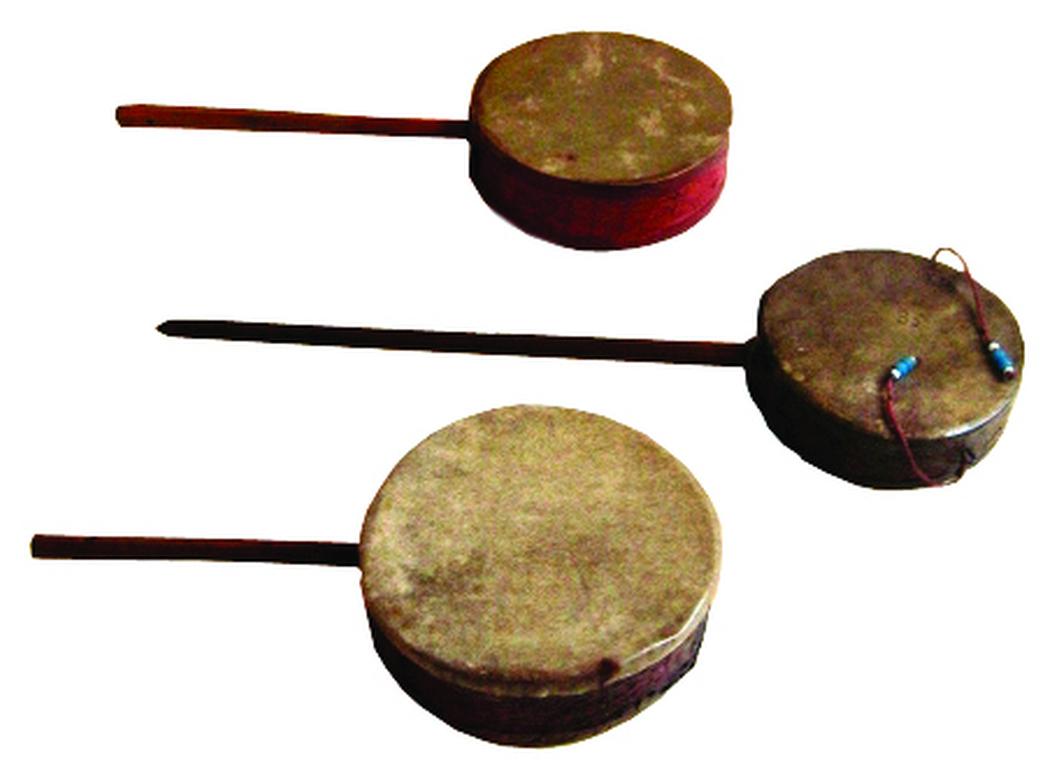

The back of the toyshops served as the place of production and the front parts were used as showcases. Toys were sold wholesale or by retail. Amongst the toys, there were hoops, cars, big wheels, soil jugs, whistles, tambourines, tabors, peg tops, balls, humming tops, wire cupboards, chairs, cradles, slapsticks, noise makers (kaynana zırıltısı), drums on a stick, bobo dolls (hacıyatmaz), mortars and pestles, churns, wooden acrobats, grasshoppers, sheep- lambs, Hacivat- Karagöz illustrations, and so on. These toys were produced till the early 20th century.

To classify some of the toys according to their kinds; cars, which had wooden tires, were pulled with a rope which was tied to the front of it. This was beneficial for children learning how to walk and contributed to muscle development. The cars also served as barrows with two push rods and a single tire and were called “push-and-pull toys”.

Toys that had mechanical features with connecting nails, wire and tin were called moving toys. These toys produced sound after a tire or another part of the toy was set in motion, and therefore they kept the children’s interest. One of these kinds of toys was a noise maker (kaynana zırıltısı). It was the toy model of nefir, which made a sound like the travelling dervishes used for scaring wild animals and keeping them away in Turkish culture. This could also be seen in other cultures such as Indian, Italian, and French.

Musical instruments both raised the level of fun of the games and improved listening skills and musical ears, thus giving a sense of rhythm and balance.

Children tried to understand and to get to know the objects and their sounds and actions. They perceived and fictionalized them through the objects belonging to grown-ups’ worlds, but the toys were suitable for their own physical features from their birth on. Miniature furniture served this purpose. Cradles, mortars and pestles, churns, wire cupboards and chairs are only some of the examples.2 These toys, which can also be classified according to various educational and entertaining aspects, were mainly made of wood. But ancillary materials like leather, paper, tin, nails and beads were also used. In addition, wooden jugs were made of red mud taken from the Golden Horn (Haliç). Mostly ornate, these toys were dyed with earth dye, yellow gilt and vivid and attractive colors like red, blue, green and white.3

Although 25-30 toy shops were open in the early 19th century, there were only 2 shops left in Oyuncakçı Çıkmazı, which was ruined by fire in the Eyüp Market in 1921. One of the last toymen, Kadir Şengöz, talks about the situation of toymanship in an interview of his in 1939: “Toymanship in Eyüp died long ago. There is only my shop and another one, two shops down now. After making one or two camels using the last wood I have, I will dismantle my worktop… Tastes have much changed. The day has come where we are unable to compete with toys made in factories in Europe, especially their tin toys.”4

Almost half a century after Kadir Şengöz’s interview (2004), Hülya Yalçın wrote about her interview with Halit Şengöz, who is the son of Kadir Şengöz:

I took over this shop which we have been running for 77 years in 1955…Not only did we make camels but also wooden double horse carriages, duck carriages, cradles, clowns, Karagöz-Hacivat, trumpets, drums, trambolines, trucks, noise makers and cradles… I am being conquered by plastic as time goes by. My late father reacted against tin toys but he dealt with it for 16 years. I gave myself up to plastic sooner. I am really sorry both because I could not maintain my father’s profession and because I witnessed the disappearance of a beauty, unique to Istanbul. In addition to wooden toys, we were also making wooden whistle pots, jugs with mirrors and goblet drums.5

When 1958 arrived, the two shops that could be considered historical were also closed. The Şengöz family’s new shop in İskele Square went on to sell toys, mostly aimed at tourists.

Toy shops in Beyoğlu

From the 20th century on, changes in the historical background of the city and the Westernization movement led to changes in theatre, opera, camera and other industrial products in addition to toy selling and toymanship. This profession livened up in splendid shops in Beyoğlu.6 The first shop that comes to minds is called Japanese Shop, which may be better known as Nakamura’s Japanese Shop. The second is Çocuk Bonmarşesi (which can be translated as Children’s Department Store), which has been open in the same location for 63 years. In addition, Karlman Passage, a few shops on Yüksek Kaldırım Street in Karaköy, and “Muppets’ Hospital” (which made tin soldiers and was in Hocopulo Passage and was a foundry which was in service till mid 1940s in Yeniçarşı) were the places where various kinds of toys could be found. It is interesting that Karlman, where toys were available near clothes, glassware and furniture, stepped into toymanship after 1926. Japanese Nakamura opened his first shop in the Çiçek Pasajı (Flower Passage), which was formerly called Cité de Péra or Hrisraki Passage in the 1910s.

In the long, wide showcases of the Japanese Shop facing İstiklal Street, where these toys presented in addition to the other goods: soldiers, castles, tanks, boats, sailing boats of every size, ships, guns, rifles, wooden swords, cowboy hats, uniforms and helmets of soldiers and firefighters, kinds of puppets, miniature kitchens, fridges, kitchen dollhouse utensils, plaster food, fruits, vegetables, roasted chickens with jardinière, cakes and ‘smoked’ jambon. Kimonos, Japanese dolls, hand-held falls, umbrellas and aquariums were displayed in the showcase on the right and the near the entrance door. The one on the left was allocated for glassware goods, Chinese or Japanese porcelain sets and vases ornamented with dragon illustrations. The author Selim İleri also mentions stone dolls, teddy bears, wooden houses, embellished cubes, Chinese lantern and caterpillars when Japanese Shop was mentioned.

A rival or alternative of Japanese Shop, which is very important and the most long living toyshop of İstiklal Street, is Çocuk Bonmarşesi. It was opened in 1930 and sold nothing but toys. Large and small puppets and war toys, earthen infantries, sailors and cavalry officers (made up of a horse and the rider) all made in Germany, were some of them. Among them were the ones who carried a flag, lied down and shot, threw hand bombs and who carried a machine gun. In addition to those, castles, trucks, motorcycles and some other indispensable objects for war games during war years were also presented. Plus, there were “village games” which were home products, produced with turning machines, sometimes in the form of a human and knocked down with a ball just like in bowling. Educational “mekanos” were composed of parts that could be added to each other. Considered as the ancestor of toy blocks (lego), mekano gave pleasure to children who built or could build bridges, cranes, and Eiffel towers. Giant tin butterflies, tipcats, bobo dolls, balls and wooden acrobats were local Eyüp products.

In the Hacopulo Passage, known as “Muppets’ Hospital”, showcases and workshops were full of kinds of dolls and materials needed for making dolls, such as hands, arms, legs, bodies and heads. Some dolls looked as if their arms had been broken, legs had been bruised, heads had been cut off or ripped and as if their eyes had been hollowed out.7

As a result of the increase in demand and range of toys in the Republican period, imports and markets fluctuated. In the town of Marpuççular, the Spiro Giokas Müessesesi was founded and Nikoli Mihalidis (b. 1916- d.1985), who was the second head, supported the manufacturers who were trying to maintain their profession for as long as they could.8 Accepted as the first manufacturer, Hamdi Dündar stepped into the toy industry with his “figured cubes”, and then developed the concept and manufactured construction games and “matador.”

Because the toy industry has evolved in time- varying tastes have developed and toys have started selling out in big stores, pharmacies, supermarkets, glassware shops and street vendors.9

FOOTNOTES

1 Sadi Yaver Ataman, Türk İstanbul, Istanbul: İstanbul Büyükşehir Belediyesi, 1997, p. 177.

2 Fadime Geleş, “Osmanlı’dan Günümüze Eyüp Oyuncakları ve Oyuncak Tarihindeki Yeri”, Günümüzde Çocuk Oyunlarında ve Oyuncaklarında Yaşanan Değişimler Sempozyumu: Bildiriler, Aralık 9-10, 2010, Ankara : Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı Araştırma ve Eğitim Genel Müdürlüğü, 2011.

3 Fadime Geleş, “Eyüp Oyuncakları-Bir Sevgi Masalı”, Oyuncak Sergisi, Istanbul 2011, p.74.

4 Hülya Yalçın, “Eyüp Oyuncakları Müzesi”, Tarihi, Kültürü ve Sanatıyla Eyüpsultan Sempozyumu VIII: Tebliğler, Istanbul: Eyüp Belediyesi, 2004, p. 69.

5 Yalçın, “Eyüp Oyuncakları Müzesi”, p. 70.

6 Scognamillo Giovanni, “Beyoğlu Oyuncakçıları”, Toplumsal Tarihte Çocuk, prepared by Bekir Onur, Istanbul: Tarih Vakfı Yurt Yayınları, 1994, p. 139.

7 Giovanni, “Beyoğlu Oyuncakçıları”, pp. 139-143.

8 Bekir Onur, Oyuncaklı Dünya, Ankara: Dost Kitabevi, 2002, p. 158.

9 Giovanni, “Beyoğlu Oyuncakçıları”, p. 139.