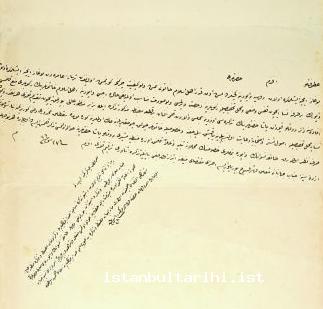

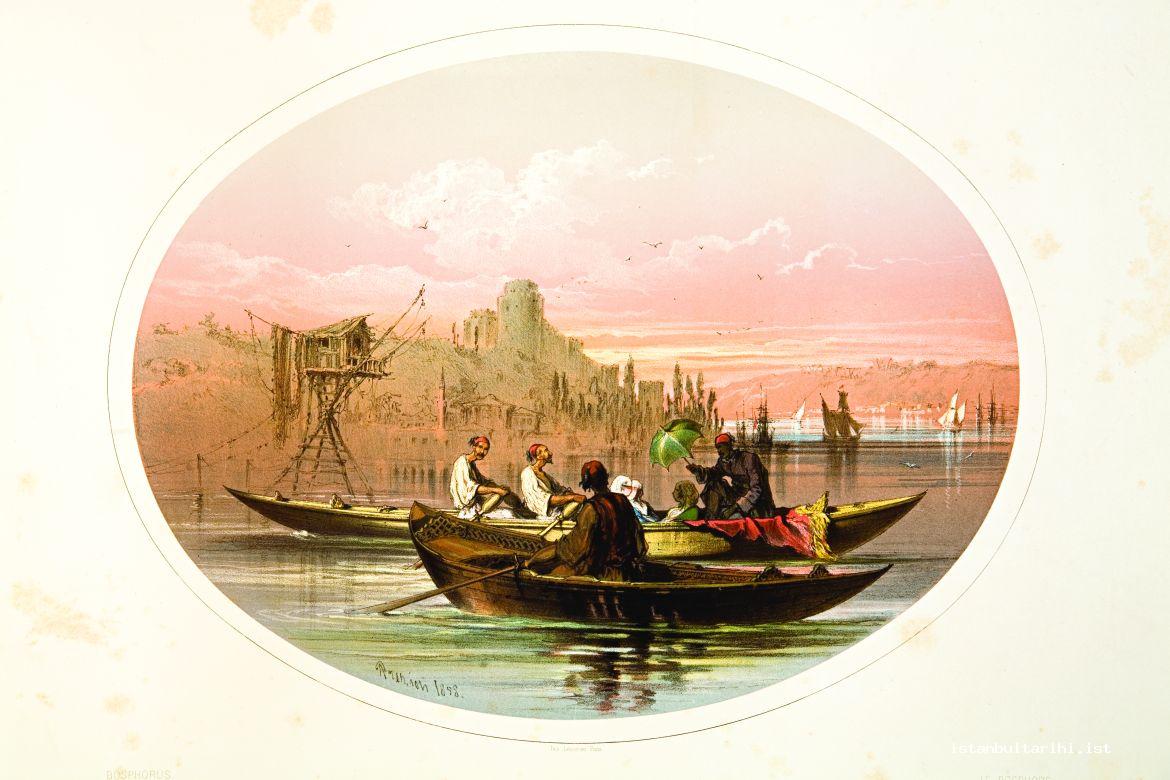

Concerning the text of the document presented below, as far as we can ascertain, following the commencement of passenger ferry transportation operations on the Bosphorus in the period immediately following the Tanzimat an interesting ban was imposed by the government. For the first time concern arose about the presence of Muslim women on the passenger ferries in Istanbul and the Bosphorus region, and it was decided not to allow them to board the boats. We learn about the existence of the ban, which stemmed from an incident in which a few Muslim women boarded a Russian ferry to travel along the Bosphorus, and its justification from the document relating to the establishment of the Şirket-i Hayriye (ferryboat company) enclosed in a larger text entitled “The Issue of the Establishment of the Şirket-i Hayriye.” At first, there were no separate seating areas for men and women on the ferries, and no adequate ports that allowed passengers to comfortably embark and disembark from the ferries existed. More specifically, ferries docked offshore and passengers were transported to the ferries with great difficulty in boats. It is precisely in relation to this situation that the ban originated. The ban stemmed from the threat posed to women, and particularly those women with children, who were boarding and disembarking from the ferries, as well as from the lack of a separate seating area for women on the ferries. Even as late as 1905, ferries approaching the Port of Yeşilköy were not able to dock, and the İdare-i Mahsusa (Maritime Administration) had to hire boats to transport passengers to the ferries and to the port; both facts clearly highlight the difficulty passengers—in particular women—experienced in the 1840s and the early 1850s.1

Upon learning the aforementioned incident of Muslim women boarding a Russian ferry, the Kaptanıderya (Admiral) Süleyman Refet Pasha suggested that some precautions be taken. He stated that if such behavior came to be looked upon favorably by the people, other Muslim women might also take the same course of action. The separation of the areas on the boats and the areas in which people waited to board the boats according to sex, as implemented on the ferries that operated between Istanbul and other ports, and the bazaar boats that carried out intercity sea transportation was proposed as a solution. Accordingly, this solution could be implemented on the ferries that operated on the Bosphorus, and separate areas for men and women could be designated. In this way, the problem would be solved and with the increasing number of female passengers, the Ottoman Imperial Shipyard ferries would be able to ensure larger profits.

In the event that the kind of solution proposed would not be found agreeable, Süleyman Refet Pasha proposed that, through the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Russian ferry company be cautioned so as to not allow Muslim women to board its ferries. It is interesting that the Meclis-i Vala (High Council), the most ardent supporter of the reforms of the Tanzimat period, in terms of both overseeing and determining reforms, formed the view that the proposal of Süleyman Refet Pasha which allowed women to board ferries was not appropriate and that the ban imposed on Muslim women should continue. According to council members there was no pressing need for Muslim women to board ferries. The difficulties that would be experienced by women boarding and disembarking from ferries and the probable accidents that would be caused by women who were at times accompanied by their children were the reasons that compelled the members to come to such a decision.

In addition to this, the assembly sent word to districts asking that women be warned not to violate the ban. These views of the assembly were approved by a decree of Sultan Abdülmecid on July 9, 1850 (28 Sha‘ban 1266 H.), and it was decided that the ban should continue. It could not, however, be expected that such an unrealistic ban would be long-lived. Thus, approximately two-and-a-half months later, with a decree from Sultan Abdülmecid, dated September 30, 1850, the Şirket-i Hayriye was formed and this ban was lifted.

Logic prevailed and the solution reached followed Süleyman Refet Pasha’s proposal. Thus “on the matter of women being able to board ferries, the view that a license be granted has been viewed favorably,” provided that areas specifically for women be built and that the staff be assigned to these areas be of a senior and trustworthy nature;2 therefore this interesting but important problem was solved.

In my humble words,

Until now, in keeping with the orders of the Grand Vizier, Muslim women have not been permitted to board those ferries operated by the Ottoman Imperial Shipyard on the Bosphorus. The other day a few Muslim women were seen on a Russian ferry that operates in Istanbul, heading for the Bosphorus, despite the operation of ferries by the Ottoman Imperial Shipyard specifically on the Bosphorus, as granted by the Sultan. It had not been deemed fitting for Muslim women to travel on foreign ferries, and it was considered inevitable that a rise in the number doing so would occur. Until now, even though women were not permitted on Bosphorus ferries, no explanation has been made for the fact that female passengers were allowed on ferries travelling to ports outside of Istanbul, and in comparison to this, there was deemed to be no obstacle to women being permitted to board these ferries.

However, as is the case with bazaar boats, women could be taken on board provided that they were veiled and were not seated with men, in a separate partitioned area on the ferry. It is deemed appropriate for action with regard to this matter to be taken in this way so that the competition threatened by foreign ferries is prevented and also so that the treasury of the Ottoman Imperial Shipyard will benefit. Therefore, through the mediation of the Minister of Foreign Affairs, in order that the aforementioned Russian ferry not permit women to board, it is deemed appropriate that the Serasker (commander-in-chief) undertakes correspondence and that we await the ruling of the written order of the Grand Vizier, who has the final say in the matter.

On 24 J[umada al-akhir] H. [12]66

Humble

Süleyman

In summary, it has been noted in the official memorandum sent by the Kaptanıderya to the Meclis-i Vala that the other day a few Muslim women were aboard a ferry operating on the Bosphorus. Despite the operation of ferries specifically on the Bosphorus by the Ottoman Imperial Shipyard it was not deemed to be fitting for Muslim women to travel on foreign ferries, and it was thought to be inevitable that the number of them doing so would rise. Women could board ferries, as is the case with bazaar boats, provided that they were veiled and were not seated with men and stayed in a separate partitioned area on the ferry. It is deemed appropriate for action with regard to this situation be taken in this way so that the competition coming from foreign ferries is hindered and also that the treasury of the Ottoman Imperial Shipyard benefits.

Therefore, it is thought to be appropriate that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs intervenes and the decision of the Sultan is sought on the matter of the aforementioned Russian ferry permitting women to board. According to the opinion of some, it would not be fitting for a license to be granted for women to travel by ferry, despite special care being taken regarding the veiling of and separate seating area for women. Thus, using the ferry is not regarded as an absolute necessity for women, and because it is anticipated that some women will be travelling with children, difficulties and accidents may arise in boarding and disembarking from the ferries; this is not comparable to the situation regarding the other types of boats.

It is for this reason that it is deemed necessary to forbid Muslim women from boarding ferries and on the point of enforcing the ban, it is required that the police chief to undertake this in the districts. This topic has been put before the Meclis-i Vala and correspondence has been undertaken with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, who will undertake whatever action is required in accordance with the order given by the Grand Vizier.

On 19 Sh[aban] H.[12]66 [seal] State Council

Your Gracious Excellency,

It has not been considered appropriate for the Ottoman Imperial Shipyard to create a separate partition on the ferry operating on the Bosphorus so that women could be permitted to board, due to the disapproval incurred by a few Muslim women recently boarding a Russian ferry operating on the Bosphorus.

Upon receiving the official memorandum of the admiral which contains the view that Muslim women should be permitted to board foreign ferries, the aforementioned mandate was penned by the Meclis-i Vala and presented to the Sultan.

In spite of the fact that due consideration would be given to ensuring that women be veiled and for there to be a separate area for them on the ferry, it would not be appropriate for women—especially concerning the matter of those boarding with children—to board due to the mishaps that might arise. Upon this matter being put forward, the Grand Vizier has delegated some duties to the police chief so that the ban be implemented in the districts and the memorandum has been written so that the Sultan may choose to issue a decree however he sees fit.

On 27 Sh[a‘ban] H. [12]66

In my humble words,

The memorandum that I have had the pleasure of receiving has been shared with the Grand Vizier and has been presented to his Majesty.

After permission was sought, after due consideration, it has been decreed that the boarding of ferries by women be prohibited; this matter was delegated to the police chief so as to promulgate the ban in the districts, and the mandate has now been given to the Grand Vizier so that he may execute the order however he may see fit.

On 28 Sh[a‘ban] H.[12]66

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BOA, İ.MVL, nr. 5212.

FOOTNOTES

1 For comprehensive information see Nezih Başgelen, “Köprü’den Yeşilköy’e Vapur Seferleri”, Çağını Yakalayan Osmanlı, ed. Ekmeleddin İhsanoğlu and Mustafa Kaçar, Istanbul: İslam Tarih, Sanat ve Kültür Araştırma Merkezi, 1995, pp. 207-211.

2 BOA, İ.DH, nr. 13077, lef 5.