Istanbul’s First Encounter with Western Music

Western music was first introduced to Istanbul as early as the sixteenth century. However, the real meeting between the two took place in the nineteenth century.

It is generally held that Istanbul’s first introduction to Western music and to the particular instruments used in its performance happened in 1543, when France’s first art-loving Renaissance king, François I (d. 1547), sent Sultan Süleyman I the Magnificent (d. 1566) a musical ensemble as a present. More specifically, it is a historical fact that two new usūls (a rhythmic pattern consisting of specific note durations and accents) known as frenkçin and frengifer (both words derived from the Turkish word for European –frenk) were created in traditional Turkish art music under the influence of the French in the sixteenth century.

Grand Vizier Köprülü Fāzıl Ahmed Pasha (d. 1676) made an attempt in the seventeenth century to have an opera troupe brought from Venice for a wedding ceremony. Sultan Selim III (d. 1808) was also fond of Western-style music and the dance that it accompanied. This perhaps accelerated the process which brought Western music to Istanbul. The first opera was thus staged in Istanbul in 1797 in the inner court of Topkapı Palace by an opera troupe, most probably procured through the efforts of the French embassy.

Opera in Istanbul in the Pre and Post-Tanzīmat Periods

The statesmen and the dignitaries of the Tanzīmat era were, so to speak, in competition with one another to imitate the West in their private and social lives. The developments witnessed in Istanbul’s own Western music culture constituted a part of this race.

Opera houses started to open in Istanbul throughout the reign of Sultan Mahmud II (1808-1839). In 1839, for instance, an Italian named Gaetano Mele managed to get permission from the sultan to open a theater in the Pera quarter (today the Beyoğlu district). Following that achievement, many theaters and concert halls were opened on the ‘Grande Rue de Pera’ (Istiklal Avenue); these were the French, Italian, Tepebaşı and Naum Theaters. In these halls, Western music concerts, operas, and operettas were performed. The Bosco Theater (also known as the Théatre de Pera or the Théatre Italien Naum), which used to be located on the corner where Çiçek Pasajı is today, basically functioned as an imperial theater under the patronage and financial funding of Sultan Abdülmecid (1839-1861). Rebuilt out of brick and stone a few years after it burned down, the Naum Theater served music lovers in a very professional manner and spread opera culture in Istanbul from its reopening in 1848 until 1870, when it burned to the ground in the great fire of Beyoğlu. The opera Belisario, composed by the famous composer Gaetano Donizetti (d. 1848) and staged in Italian in the Bosco Theater in Istanbul in 1841, was the first Italian opera ever performed in Istanbul. The same opera was also performed in the harem of Bezmiālem Vālide Sultan (d. 1853) at the beginning of 1843. The vālide sultan and her female servants followed the opera with the Turkish translation of the libretto in their hands. In April 1868, Edward, Prince of Wales, who was to become King Edward VII of England (d. 1910), his wife, and, at a later date, the Austrian emperor Franz Joseph (d. 1916) watched operas in the Naum Theater.

Residents of Pera had the opportunity to watch the works of composers such as Donizetti (d. 1856), Bellini (d. 1835), Auber (d. 1871), Meyerbeer (d. 1864), Verdi (d. 1901) and Berlioz (d. 1869) very shortly after their premiers. Try to imagine this: the Levantines living in Pera were able to watch Verdi’s Il Trovatore only 10 months after the opera’s premier in Rome in January 1853, and exactly three years before Parisian music lovers were able to.

Istanbul’s theaters made very tempting offers to European artists of the time. In 1856, Luigi Arditi (d. 1903) received offers from three opera companies to be their conductor. As Arditi reports in his own memoirs, the reason why he chose to come to Istanbul was that, of all the three opera companies, it was the Naum Theater that offered the highest salary.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, the cultural activities in Istanbul were of such a caliber that they could rival any of their peers in major European cities. One evening in 1895, the Barbe-Bleue opera by Offenbach (d. 1880) was staged in two different theaters in Istanbul. In 1896, residents of Istanbul had a chance to choose one of the three Aida performances being staged in their city on the same evening.

In addition, almost every Istanbul harem contained a piano, and ladies would play pieces from memory rather than reading from sheet music. A piece that would very often be heard on these pianos was Lyre Orientale, harmonized in 1858 by Callisto Guatelli (d. 1900), the music director of the palace. This novel anthology, which contained French and Turkish texts, and Turkish songs adapted for the piano, was dedicated to Necip Pasha.

Famous European Musicians Who Gave Concerts in Istanbul

Undoubtedly, the most significant factor that contributed to the rise in admiration for western music in Istanbul was the concerts given by famous foreign virtuosos. The first among these to visit Istanbul was the Austrian super-virtuoso Leopold de Meyer (1816-1883), renowned as “the Lion Pianist”. A news report from Europe dated October, 1843 explains that:

Pianist Leopold de Meyer played in the presence of the sultan in Istanbul—this makes him the first well-known musician to play in Istanbul... After a private concert, the famous pianist was given a snuff box decorated with diamonds by Sultan Mahmud II [sic: Abdülmecid].

De Meyer played in Istanbul twice more in the presence of Sultan Abdülmecid, in 1856 and 1857. At one of these concerts forty women from the palace listened to the concert from behind screens.

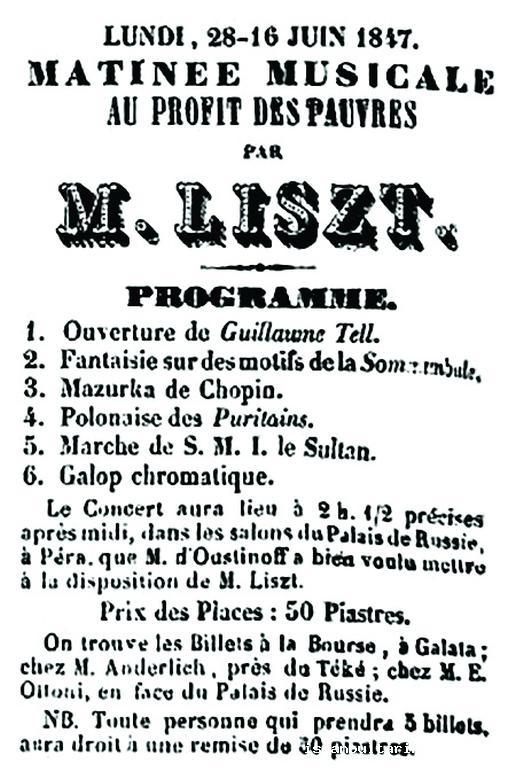

However, the most famous musician ever to play in Istanbul was Franz Liszt (1811-1886). Liszt came to Istanbul from Galatz by ferry on June 7, right before the last concerts he was scheduled to give in Russia in 1847. He left Istanbul on June 13 after performing twice in the presence of Sultan Abdülmecid in Çırağan Palace. One of the most important pieces performed by Liszt in Istanbul was Grande Paraphrase de la Marche de Donizetti, which he had composed in Istanbul and dedicated to Sultan Abdülmecid. This work was based on an existing theme by Giuseppe Donizetti, the conductor of the Ottoman Royal Military Ensemble. Another work of significance by the musician, on which he worked in Büyükdere, was a fantasia on Verdi’s opera Ernani.

The Imperial Band (Muzıkā-yı Hümāyūn)

The Tanzimat Edict of 1839 is considered to be the starting point of the official process of Westernization in the Ottoman Empire. This Westernization phase started in music after Sultan Mahmud II’s abolition of the Janissary Corps in 1826; he subsequently abolished the Ottoman Mehter (Military Music) Band in 1827, and established the Imperial Band. Even though it was established with the aim of providing military music education, this institution grew into the first conservatory of the Ottoman court. This organization encompassed several ensembles of various types, such as the palace military band, the opera and operetta troupes, a Turkish music band, and a choir.

A Frenchman named Monsieur Manguel was the first foreign commander of the Imperial Band. In 1828, an Italian military band musician, Giuseppe Donizetti, the older brother of the famous opera composer Gaetano Donizetti, was appointed as head of the ensemble. After exerting great efforts to make Western music gain currency in Istanbul and rising to the rank of pasha, Donizetti died in 1856; another Italian, Callisto Guatelli, was appointed as commander of the Imperial Band in his place. Guatelli served as private tutor to Prince Abdulhamid, and also worked for some time as a conductor at the Naum Theater.

Donizetti composed the Mahmūdiye March for Sultan Mahmud II and the Mecīdiye March for Sultan Abdülmecid. Guatelli composed the Azīziya and Osmāniye marches as well as the music for the international fair held in Istanbul in 1863. Guatelli wrote a number of pieces with themes related to Istanbul and the Bosphorus.

The first Turkish director of the Imperial Band, as well as the first Turkish orchestra conductor, was Colonel Safvet Atabinen (1858-1939), a flutist trained in the Paris Conservatory. The last commander of the Imperial Band was Osman Zeki Üngör (1880-1958). He was the first conductor of the Presidential Philharmonic Orchestra in Ankara during the Republican era, as well as director of the Music Teachers’ College.

Music in the Palace

Sultan Abdülmecid was the first sultan to receive Western music lessons and also the first to play the piano. Sultan Abdulaziz and Sultan Murad V composed some pieces for the piano. In addition, Sultan Abdulhamid II took piano and classical Western music lessons when he was a prince.

In addition to foreign musicians, talented Turkish musicians also performed in the extravagant theater built in the Dolmabahçe Palace complex during the reign of Sultan Abdülmecid. For example, Zeki Bey, who had served as the Turkish consulate in Messina, performed in this theater as a tenor and sang operatic duets with the famous soprano of the time, Adeline Murio-Celli.

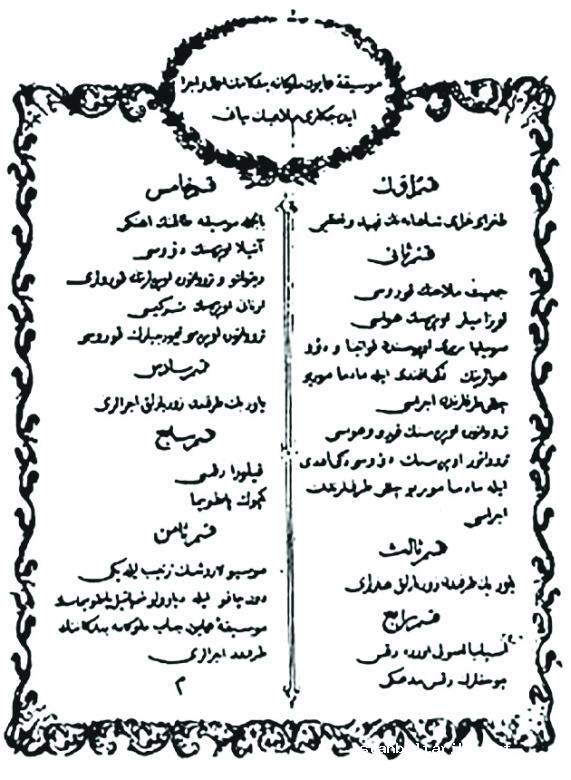

Adeline Gautier (Murio-Celli), one of the divas of the nineteenth century, was appointed as a court musician after coming to Istanbul in the year that Arditi was the music director of the Naum Theater. Among her obligations she was to perform at important receptions and to teach the nearly 300 women living in the harem section. The content of the program of Murio-Celli’s last performance in the sultan’s presence in 1862, before her departure from Istanbul, was interesting. In this program, which dazzled the audience with its pantomime, dance, and acrobatic shows, we also find the performance of the following operatic selections:

The Choir of the Society of Mariners

An aria from the opera Luisa Miller

The performance by Zeki Efendi and Madam Murio-Celli of the “Kavatina” and “Duke” arias from the opera The Barber of Seville

The chorus and an aria from Il Trovatore

The chorus from Il Trovatore, performed by Zeki Efendi and Madam Murio-Celli

The harmonic performance by the entire ensemble

A chorus from the opera Atilla

Choruses from various Rigoletto and Il Trovatore

A türkü (folk song) from Ernani

The Anvil Chorus from Il Trovatore

A performance by His royal servants, the Imperial Band

Istanbul Masters of Western Music and Western Music with Istanbul Themes

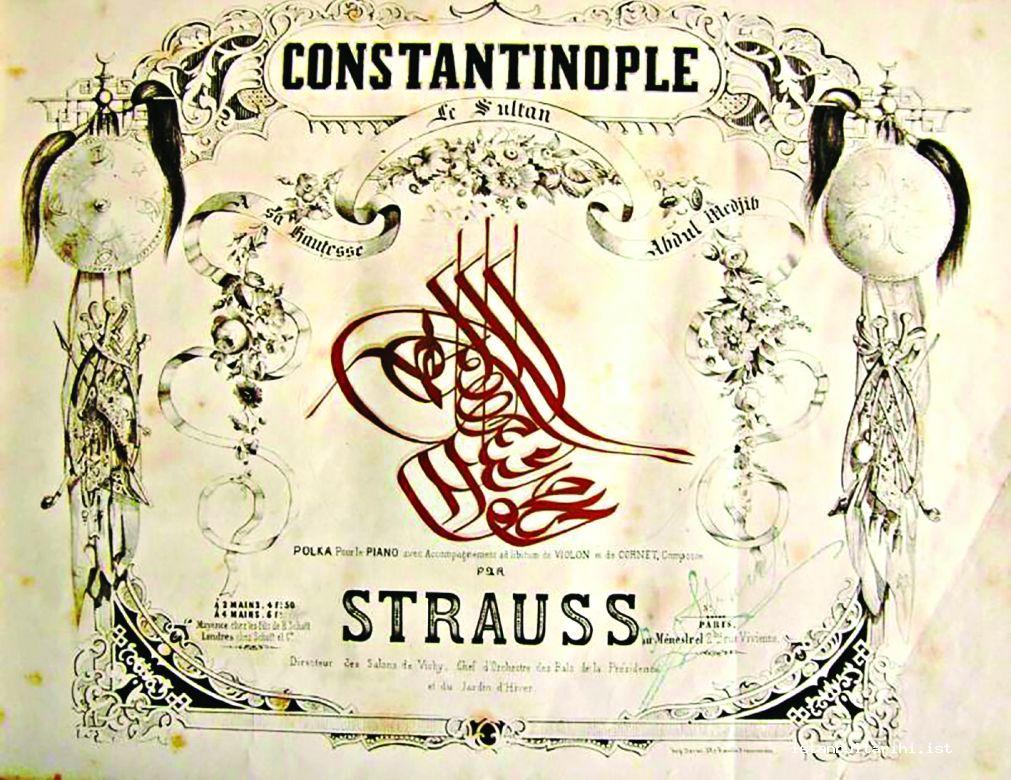

There are various compositions dedicated to Ottoman sultans and statesmen by the famous Strauss family, who were active during the nineteenth century. The title of one of these dedicatory compositions is Constantinople. Not all the musicians with the surname ‘Strauss’ belong to the Strauss family. For instance, the polka, the title of which is given below, entitled Constantinople and sent to the Ottoman court in dedication to Sultan Abdülmecid in 1849, was composed by a French composer named Isaac Strauss. This musician’s surname being the same as that of the Viennese Strausses has troubled music historians for a long time. Moreover, there is a magnificent piece composed in 1892 and dedicated to Sultan Abdulhamid II by Johann Strauss II (the Son), the “King of the Waltz” and the composer of the Blue Danube. This piece is entitled Tales From the Orient (Märchen aus dem Orient, Op. 444), and on the original cover page of the score there is the silhouette of an oriental city that resembles Istanbul.

There was a surprising number of publishing houses dealing in the business of publication of musical scores in Istanbul during the nineteenth century: Alexander Comendinger, Kuigi Bellolo, G. Balatti, J. d’Andria, Sotiri Christides, S. Hovsépian, H. Aramian, Karekin Kavafian, Şamlı İskender, Osmaniye Matbaası, and Pascal Keller, among others.

Western music first came to Istanbul through Italian musicians, and then it became established through the efforts of musicians from a variety of countries. The most famous operetta composer of Istanbul in the nineteenth century was Dikran Çuhacıyan (1837-1898), known as “the Verdi of the East.” His first operetta, Leblebici Horhor (Horhor the Roasted Chickpea Seller), was very successful in Istanbul. He composed two more operas, which were entitled Arif’in Hilesi (Arif’s Trick) and Zemire. Bartolomeo Pisani (1811-1893) lived in Istanbul for many years and was appointed head of the Imperial Band in the absence of Guatelli. He composed works with Istanbul themes, such as Sul Bosforo: Notturnino a due voci and Sur le bleu Bosphore: chanson byzantine. Among other Italian musicians working in Istanbul, we can mention Italo Selvella (1863-1918) and Augusto Lombardi (1844-1913). Istanbul also boasts musicians of Hungarian origin, such as Alessandro Voltan (Macar Tevfik) and Géza Hegyei (1863-1926), a student of Liszt who settled in Istanbul and gave piano lessons. Hegyei taught music to Şadiye Sultan and Ayşe Sultan, daughters of Sultan Abdulhamid II. Among the musicians residing in Istanbul in the nineteenth century, we can also mention the British Paul Cervati (1815-1897), the German Paul Lange (1865-1920), and the French-educated Italian Enrico Henri Furlani (1870-1940).

One of the most important Istanbul musicians in the 19th and twentieth centuries was the pianist Faik Bey, whose real name was Francesco della Sudda (1859-1940). Authorities called him “the supremely gifted Turk”, “the latest storm brewing among piano virtuosos”, “a major talent”, and “a great virtuoso”. He trained under Franz Liszt for more than three years in Weimar, during which time Liszt gave him the affectionate sobriquet “Der Pasha”. After he returned to Istanbul, Sudda became the piano teacher of Zeynep Altar, the wife of Cevat Memduh Altar, and took up residence in Faik Pasha Road in the neighborhood known today as Çukurcuma; another Liszt student, Géza Hegyei, also lived in this street.

All born in the first years of the twentieth century, the five great Turkish composers Cemal Reşit Rey (d. 1985), Ulvi Cemal Erkin (d. 1972), Hasan Ferit Alnar (d. 1978), Ahmed Adnan Saygun (d. 1985), and Necip Kazım Akses (d. 1999) received advanced music education abroad and became known as the Turkish Quintet in Istanbul. Each one developed a special bond with the city of Istanbul. Except for the İzmir-born Saygun, and Jerusalem-born Rey they were all born in Istanbul. After his training in Geneva, Cemal Reşit Rey returned to Istanbul and founded the City Orchestra, and for years thereafter he worked as a teacher in the Istanbul Conservatory, starting from the years when it was known as Darülelhan.

The real era of operettas began in Turkey after Çuhacıyan with the works of Cemal Reşit Rey. Starting from the second half of the twentieth century, Rey composed operettas such as Üç Saat (Three Hours), Lüküs Hayat (Luxurious Life), Deli Dolu (The Foolhardy), and Bir İstanbul Masalı (An Istanbul Tale) with his brother, the librettist Ekrem Reşit Rey; he also portrayed the conquest of Istanbul with a symphonic poem that he wrote in 1953 entitled Fatih. There is another work with the same theme by Kamran İnce, which he composed in 1994 and entitled The Fall of Constantinople.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

And, Metin, “1855 Yılında İstanbul’da Söylenen Silistre Kuşatması Adlı Kantat”, Devlet Tiyatrosu Dergisi, no. 10 (1963).

And, Metin, “Eski İstanbul’da Fransız Sahnesi”, Tiyatro Araştırmaları Dergisi, no. 2 (1971), pp. 72-102.

And, Metin, “Opera and Ballet in Modern Turkey”, The Transformation of Turkish Culture: The Atatürk Legacy, ed.Günsel Renda and C. Max Kortepeter, Princeton: Kingston Press, 1986.

And, Metin, “Türkiye’de İtalyan Sahnesi”, İtalyan Filolojisi, 1970, no. 1-2 (1970), pp. 127-142.

Aracı, Emre, Naum Tiyatrosu, 19. Yüzyıl İstanbulu’nun İtalyan Operası, Istanbul: Yapı Kredi Yayınları, 2010.

Arditi, Luigi, My Reminiscences, New York: Mead and Company, 1896.

Baydar, Evren Kutlay, Osmanlı’nın Avrupalı Müzisyenleri, Istanbul: Kapı Yayınları, 2010.

Cazaux, Christelle, La Musique a la Cour de François I, Paris: Ecole nationale des chartes, 2002.

Eğecioğlu, Ömer, Müzisyen Strausslar ve Osmanlı Hanedanı, Istanbul: Yapı Kredi Yayınları, 2012.

Engel, Carl, “The Literature of National Music”, The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular, vol. 19, no. 426 (1878), pp. 432-435.

Kosal, Vedat, Osmanlı’da Klasik Batı Müziği, Istanbul: Eko Basım Yayıncılık, 2001.

Kösemihal, M. Ragıp, Balkanlarda Musıkî Hareketleri, İstanbul: Numune Matbaası, 1937.

Loewenberg, Alfred, Annals of Opera 1597-1940, 3rd ed., Totowa: Rowman and Littlefield, 1978.

Millas, Akylas, Pera: The Crossroads of Constantinople, Atina: Militos Editions, 2006.

Oransay, Gültekin, “Music in the Republican Era”, The Transformation of Turkish Culture: The Atatürk Legacy, edited by Günsel Renda and C. Max Kortepeter, Princeton: Kingston Press, 1986.

Parkes, Albert L., “Great Singers of this Century”, Godey Magazine, 1896, vol. 133 (1896), no. 795, pp. 290-295.

Sevengil, Refik Ahmet, İstanbul Nasıl Eğleniyordu?, prepared by Sami Önal, Istanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 1985.

Sevengil, Refik Ahmet, Opera San’atı ile İlk Temaslarımız, Istanbul: Maarif Vekaleti, 1959.

Şehsuvaroğlu, Haluk Y., İstanbul’dan Sesler ve Renkler, Istanbul: Türkiye Sınai Kalkınma Bankası, 1999.