“Istanbul, my city, the orchestra of time”

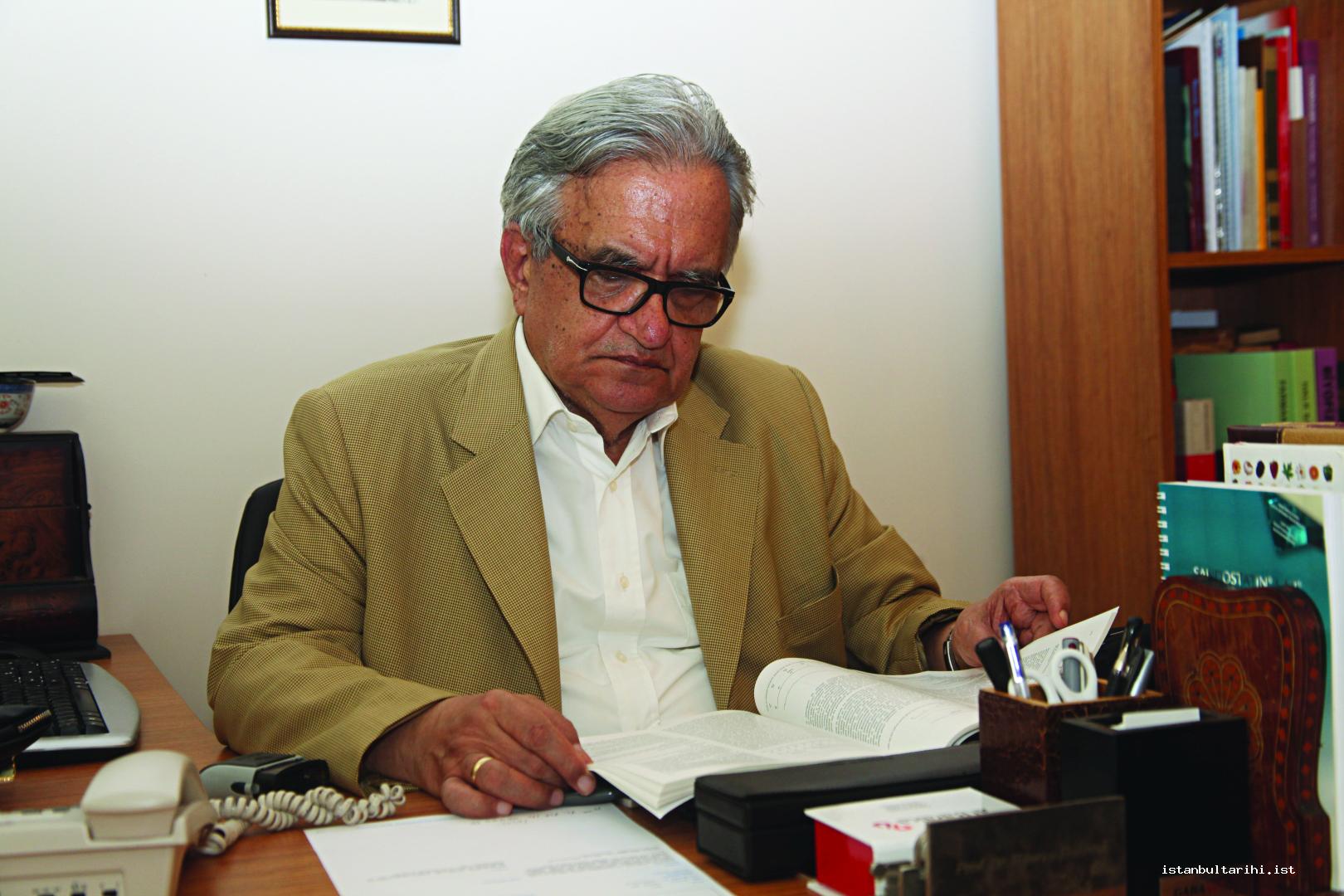

Hüsrev Hatemi, 1966.

Originally the child of a family from Tabrizi, you first opened your eyes in Feriköy, Istanbul. Could you tell us about Feriköy, this neighborhood of your childhood and youth, the house in which you were born and raised, the street and the people?

My twin brother Hüseyin Hatemi and I were born on December 12, 1938, at around 2:30 or 3:00 in the afternoon. The location was Modern Apartment, which still stands on Kurtuluş Tram Street. It was the year that Atatürk died. Although we were due in less than a month, my mother had gone to Dolmabahçe Palace with a neighbor lady and passed in front of the catafalque. The following day people were crushed in the crowd there, and my mother always said “you were almost not born, because I would not have been alive!” Hüseyin and I recall black and white film-like scenes from the year 1942, when we began understanding the world around us: the doorman Mıgırdıç Agha, Yorgo, the son of our Greek landlord Monsieur -the same age as my brothers’, Cevza Abla, my elder sister’s friend when she started middle school, a girl who would often stop by.

Cevza, if I remember correctly, means the Gemini, the star sign…But I’ve never heard it used as a person’s name.

Indeed, the name Cevza is quite rare. Our interpretation of the name as “Ceviz Abla” (walnut sister) made our elder sister angry. Again, what we remember from the years 1942-1943 is like black and white films. There is a “German war” abroad. “The German are bombing the British, the British are bombing the Germans”. Between 1942 and 1943 when we began to be aware of ourselves, what remains in our memories was getting on and off streetcars on Kurtuluş Tram Street. Taxi traffic was very infrequent. Minibuses (dolmuş) would only start to run there five or six years later. Probably in the second half of 1943, we moved to a two-story house on Çobanoğlu Street, Feriköy, just up and across from the Modern Apartment, which opened out to Baruthane Street. When my father came home from his shop, he would walk around his room-sized garden and water the flowers he had planted in the summer months. In those years, shopkeepers did not have the luxury of going on holiday. Like my father, who owned a stationary store, the grocer Monsieur Niko, the butcher Ahmet Bey and so many others also worked every weekday save Sundays - Saturdays became a holiday only after many years. In those years, during the summer holidays, the teachers working in the elementary and secondary schools coastal cities were allowed to use the classrooms as hotel rooms, moving the desks and chairs out into the corridor. Maybe the army had the same opportunity, but I don’t know. In short, until the beginning of the 1960s, whether in the public or the private sector, the workers went on holiday not to Bodrum or Antalya, but to their hometowns. Tradesmen, on the other hand, would have to be content with Sunday, due to the fear of losing customers or being labelled shirkers. While on Tram Street apartment buildings were common, all the houses on Çobanoğlu Street in Feriköy were two-storied. Each two-story house had three adjacent neighbors, one on the right, another on the left and one garden neighbor. Male neighbors greeted each other saying “akşam şerifler hayr olsun” (may your evening be blessed) and “sabah şerifler hayr olsun” (may your morning be blessed). The third neighbor, the garden neighbor, was due to the fact that the gardens from Kuyulubağ Street and Çobanoğlu Street joined one another.

I suppose you had a great deal of non-Muslim neighbors.

Certainly, in those years, the number of Greek and Armenian neighbors residing in neighborhoods such as Tarlabaşı, Samatya, Bakırköy, Ortaköy, Galatasaray and Tünel, was high. On Çobanoğlu Street, Feriköy, starting from the 1920s, middle-class civil servants, retired officers and Anatolian tradesmen started to settle here in greater numbers; the number of Christian or Jewish neighbors was around thirty percent. However, two hundred meters to the right or left the situation changed. This was a characteristic of old Istanbul. For example, the area from Haseki to Cerrahpaşa; nearly every hundred yards you would encounter another remarkable neighborhood. The Yusufpaşa, Haseki, Cerrahpaşa, Cambaziye District, Etyemez, Samatya, Hekimoğlu Ali Paşa and Davutpaşa districts were all within striking distance. As Feriköy was a relatively new district, the spiritual ambiance of the street changed even by the street, not just the neighborhood. The vicinity of Galata Tower and Halıcıoğlu, Hasköy and Balat were Jewish neighborhoods. Çobanoğlu, Lala Şahin, Kuyulubağ, Şahap, Avukat, Havuzlubahçe, Baruthane, and Ergenekon Streets all seemed to be separate districts of the city. Havuzlubahçe was a street of tree-lined gardens and modern villas with gated doors. Çobanoğlu Street seemed to be the same age as the Republic, with charming two-story houses built by Greek or Armenian engineers or master builders. On the side of the Feriköy Sports Club, the more modest Feriköy homes could be seen. This route took us to Feriköy Mosque, to the “Festival Place” for religious holidays and to the sorrowful Feriköy Cemetery, which was there at that time.

I know this cemetery made an impression on your memories. Could you tell us a little bit about Feriköy Cemetery?

Feriköy Cemetery was sad. The large number of tombstones written in Arabic letters in Karacaahmet and other old cemeteries made death remote to us. However, in Feriköy Cemetery, we would read tragic epitaphs, almost all of which were in the Latin alphabet, and grieve. A mother had written the following epitaph for her son Erhan, who died when he was about our age: “Mom, get up/Turn on the lights /Your baby bird has been shot / Won’t you dress his wound?” What else could such a tombstone do but upset me and Hüseyin, who were only seven or eight years old at this time? The reason why the “death” theme occurs a little more place in my poems was because my mother, who did not have any relatives residing in Feriköy, took Hüseyin and me to Feriköy Cemetery with her to satisfy the her need for mourning.

In fact, in the 1940s, in order to grieve or mourn, one did not have to visit the cemetery. I know from what my deceased mother told me and of course from what I read.

You are quite right; the grief that descended on Istanbul in the 1940s can be connected to more than one reason. The primary reason was the dire straits in which people found themselves. Only about twenty years had passed since the War of Independence had come to an end. Before that, the public had been greatly affected by World War I and immediately after that by the invasion of Istanbul and İzmir. Also, malaria and tuberculosis had decimated the people. Malaria inspired Sabahattin Ali’s stories; tuberculosis influenced the autobiographical and fictional writings of Rifat Ilgaz. Nazım Hikmet, who was in prison at this time, only to appear on the scene in the 1950s, also dramatically relates the terrible life conditions experienced by Anatolian peasants in “Human Landscapes from My Country”. Secondly, there were the specters of war... Pro-Germans were afraid of “What if Russia wins...”, and pro-Russians were afraid of “What if Nazism comes here”. However, there was not such great polarization among the public as there is today. Being pro-Hitler or backing Stalin, as related by Halide Edip and Nazım Hikmet, was definitely based on actual observations. However, as the middle and low-income families were in a “God forbid us from going to war” mode during the war, in the worlds of seven-to-eight-year-old children, names like Hitler, Stalin, Churchill, Roosevelt were oft-heard phrases related to the war. In my immediate environment there were very few adults who were going to university. My brother started university in the autumn of 1949. It was my impression that the young people who were ten years older than myself were interested in the war and that they tended to be pro-British, keeping away from Hitler and Stalin.

What are your memories of the blackout nights, which were engraved on the memory of people who lived at that time?

Voluntary blackouts were often carried out during the war period; and blue or navy packaging paper was constantly stuck on the windows. Alarm sirens were sometimes sounded for civil defense training. Sometimes, upon the news of sighting of German aircraft, as there were no air-raid shelters, people sought sanctuary in the basements of the houses. Between 1943 and 1944, because we were children of only five or six years, we were terrified by the white long-legged spiders that lived in the coal bunker, and would cry relentlessly due to our fear of spiders rather than of bombs. At night, search lights would look for planes in the Istanbul sky and light beams would cross each other. Some of the people called these machines “flashers”.

Times must have been very hard.

Very hard indeed.... Between 1943 and 1944, one of the dramatic scenes that left its mark on us was people fainting from hunger in the street and others rushing out of the houses with food for them. Two incidents haunt me all the time. First, one day a man dressed in a new clean coat fell to the ground; the neighborhood women rushed to his side and he told them that he had not eaten anything for three days. Some food such as fresh beans, a little spinach and a slice of bread, which was a treat in those days, was brought to him from the wire-front kitchen cabinets of the houses—as you know, the cabinets that were protected with a wire from the flies but did not have a cooling feature, thus they were called wire-front kitchen cabinets. The young man said, with tears in his eyes, that he was a university student; after eating this food and drinking some water, he left the street, hanging his head. Another scene engraved on my mind is of a neat, brown-haired man of 40 to 50 years. After wiping away his tears, he explained that he had fainted from hunger, and, again, treats like spinach, fresh beans and bread were brought to him from the houses. Refrigerators were first seen on our street a year or two later, in 1947-1948, after the war ended. The ratio of the houses that had refrigerators, which never even appeared in some other neighborhoods, was generally one in fifteen. Little children were sent to homes with refrigerators and requests were made like “Mom says hi. Would you please put this 250-gram minced meat in your refrigerator?” Tomorrow she will take it back”. There were no domestic refrigerators. The brands of refrigerators were typically English Electric, Kelvinator, or Frigidaire. The first domestic refrigerators would only be seen around 1958-1960. After 1958, wire-front cabinets remained only in low-income neighborhoods. Since the 1980s, I have not encountered that old friend, the wire-front cabinet.

What were your neighbors like in Feriköy? Did you have any remarkable neighbors?

On the Şişli side of our house lived the National Education supervisor, Nuri İmece, and his family, that is Nuri Bey Amca and Melahat Hanım Teyze; on the Kurtuluş side was the accountant Saim Tüzün and his family, that is Saim Bey Amca and Zafer Hanım Teyze. Our other neighbor on the Kurtuluş side, next to Zafer Hanım, was Mr. İstrati, who was of Greek origin. He lived with his Italian wife and their son Hrisantos, who was a law student. Sahure Hanım lived in a single room that she rented in this two-story house. Sahure Hanım, who always fastened her white hair with a hair band and walked around in a skirt and blouse or a skirt and a cardigan, sought refuge in this street of Feriköy after losing her husband; she took the surname “Birben” [me only] with the introduction of the Surname Act as an expression of her loneliness. Her white-haired and bow-tied husband gazed down on us from the wall of her single room. Sahure Hanım’s uncle was one of the representatives of the Second Constitutionalist Period, Ali Naki Efendi, and he was a founder of the Darüşşafaka. He was referred to as efendi because he had received his education in a madrasa.

Did Sahure Hanım not have any other family?

She did. She had two sons and grandchildren. Sometimes one of her sons or Remzi, one of her grandchildren, would come to visit Sahure Hanım. Remzi was the same age as us. One day, as he was singing for Sahure Hanım with his father, Remzi’s voice and his ability to carry Mr. Şevki’s artwork filled me with feelings of envy. The song was “There is no such vicious a wound as a callous word/ There is no remedy for heartache in this world”. Sahure Hanım’s only visitor outside of her family was Namık Kemal’s daughter-in-law, Celile Bolayır, who was the wife of Ali Ekrem Bolayır; the latter had recently died. Sahure Hanım asked that my mother not mention Cezmi and his suicide when she was with Celile Hanım, who was living with the memories of her only son Cezmi. Cezmi had fallen in love with a Swiss woman and committed suicide as a result of his love; Ali Ekrem Bey felt so much hatred for the woman that he wrote a stanza ending with the line “If I were a murderer, I would kill that damned woman”.

I wrote an article about Namık Kemal’s sons and grandchildren. Cezmi fell in love with a married Belgian woman in Büyükada; he had been taking violin lessons from her. Due to the pain of unrequited love, he committed suicide. However, the stanza by Ali Ekrem Bey that you mentioned indicates that this love adventure might have occurred in a different way. This needs to be researched. When did Sahure Hanım pass away, hocam?

Sahure Hanım used to say that Ali Ekrem Bey was angry with that lady because she flirted with Cezmi in vain. The exact form of the stanza that ends with “I would kill that damned woman if I were a murderer”, if I am not mistaken, is recorded in the article “Ekrem Bey” in İbrahim Alaaddin Gövsa’s Meşhur Adamlar Ansiklopedisi. Sahure Hanım died in her single room on a hot summer day in the year 1950; the day we received our elementary school diplomas and the Democrat Party period started, after the May 14th elections. Two or three hours before her death, I went to see her for the last time. My brother did not want to see her in that condition. By the way, Sahure Hanım presented us with Tevfik Fikret’s first edition of his book of children’s poems, Şermin. My brother and I used this book as practice for reading Ottoman Turkish. This book was our first step to reading old books published in the Arabic letters.

It is touching that the elderly women of the neighborhood made the strongest impressions on your memories.

Yes, Nadire Hanım is another woman I remember fondly. On Çobanoğlu Street, there were three houses across from us. Next to the third house on the Kurtuluş side, large vegetable gardens and fields started. Next to the first house on the Şişli side there was a coal yard. That “first” house I mentioned, the one next to the coal yard, belonged to Nadire Hanım and Mehmet Bey, both of whom were retired workers from the palace. Nadire Hanım was in her seventies in the 1940s. Mehmet Bey, who was older than her, would sit in his long nightgown on the sofa in front of the window and watch the street from morning until dark. He was not paralyzed. But none of the residents ever heard his voice, probably because he did not like to speak. Mehmet Bey died in the late 1940s. Nadire Hanım lived five to ten years more. She was Circassian; she used to tell her story of being kidnapped when she was nine or ten years old by a slaver and taken to the palace.

So the “palace lady” from your neighborhood was Nadire Hanım, then...

Yes, the lady from palace…The most architecturally beautiful house of the street was bought and given to them for their retirement. The story of being kidnapped from Caucasia made my mother cry and affected my brother and me deeply: “I was a nine-year-old girl, Cemile Hanım, and we were in a small village or town. One day I went out to play in front of the door. Suddenly a hand closed over my mouth. A man with a mustache took me on his horse. He made his horse gallop for hours. Then we came to a shore. They shoved me into the warehouse of either a barge or a sea vessel. I did not know Turkish. While I was crying to see my mother, the mustached slaver kept opening his eyes wide in such a frightening way that I would cry once again, although I had been silent for some time. Then, my dear Cemile Hanım, I served a lady for many years in the palace. After fifteen years, I married Mehmet Bey, who was working as a male servant in the palace. We were given this house we are living in now as a gift.

Hocam, slavery was prohibited in the early 1850s in our territory. During whose reign did Nadire Hanım end up at the palace?

Now I regret that my mother never asked whether it was the reign of Sultan Abdulhamid or Sultan Mehmed V. Although I was a quite curious and mindful, it seems that I wasn’t enough of either, as I never asked any such questions. I suppose that slavery went on for a little longer illegally, not only in Circassia, but also in Ethiopia. Unlike Sahure Hanım, Nadire Hanım wouldn’t talk to children much. Because my grandmother spoke Azeri Turkish, Nadire Hanım didn’t choose her as her confidant, preferring my mother. As Nadire Hanım said that she had been married for fifty years in 1947 or 1948, her departure probably occurred between 1897 and 1898. In other words, during the reign of Abdülhamid II. As a matter of fact, a house was not given as a gift to palace retirees during the Sultan Mehmed V period. There were many other examples in Istanbul of the style of the house Nadire Hanım resided in; it was meticulously built by Greek engineers and master-builders. It was a house with colorful tiles under the roof, over the windows on the second floor. Previously an owl had made a nest on the roof of this house. At dusk it would send signals, as I remember, to the street at regular intervals; they sounded like “pisshh pisshhh”. Nadire Hanım would get angry with the neighbor ladies who said “It brings bad luck; break up his nest Nadire Hanım!” One day, she told my mother, “The neighbors are wrong. The owl is a very propitious bird. It brings luck to the house where it makes its nest. Calling it ‘baykuş’ is a sin. This bird is called “murat (wish) bird”.

It seems Nadire Hanım was actually a very pleasant, colorful Istanbul lady.

Yes, she was idiosyncratic. She used to cover her hair with a scarf but wouldn’t try to hide all of her hair. As she was a lady from the palace, she was different from middle-class Istanbul ladies. She liked going to the cinema and looked for someone to whom she could recount these movies to, from beginning to end; the listener was generally my mother. Nadire Hanım would ring our bell at around ten in the morning. Even though my mother loved the cinema very much, due to the conditions of the time, and as she was wary of upsetting her mother-in-law, she could go six or seven times a year. My mother would make a cup of coffee for herself and Nadire Hanım and then start listening. Nadire Hanım narrated the movies, accompanying the words with gestures and short dances. For example, she would say, “Suddenly, the girl started to dance when she realized the young man she was in love with was watching her from afar. She cried, ‘There he is, there he is,’ as she danced”. She stood up, demonstrated for a short time and sat down. On another day, while telling how: “the girl looked at the man angrily and cried ‘hard hearted’”! She shouted so loudly that I and Hüseyin were both startled.

My maternal grandmother, on the other hand, was a Hüseyin Rahmi Gürpınar character who came from Tophane to see us. Another one of her prominent features was that she was very affectionate and kind to everyone. My grandmother—that is my paternal grandmother—used to walk around at home and in the garden wrapped up in a thin piece of fabric called a “çadira” because she was not used to wearing the elastic-lined charshaf (chador) back in Azerbaijan, When she was going somewhere, she wore her lightweight black coat and black patent leather shoes with her black gloves. She used to cover her head like my other grandmother used to, but her style of tying the scarf was not a “fastening”. My mother was bare-headed at home or in the garden; in the street, however, her hair was covered with a small amount of hair visible from the front.

Was your grandmother from Istanbul? You begin one of your poems with the verse “With the last Istanbulite grandmother / the word ‘kumpanya’ died as well”.

Yes, in this poem from 1975 “grandmother” is my actual grandmother. Her name was Hanım. In Kars and Iğdır the name Hanım is still in use. My grandmother and my grandfather Bilal Bey were born in the Azerbaijan region of Iran in the city of Dilman, in the Muğancık village. My grandfather, who was the first to migrate to Istanbul, opened a tobacco shop near the Karabaş Tomb in Tophane. After a while, my twelve-year-old grandmother came to Istanbul. Four or five years later, these two young relatives were married. My grandmother was supposedly born in 1885 and my grandfather Bilal was born in 1875. Before I and my brother Hüseyin were born, our grandfather passed away. My grandmother lived until 1966. She had a list of memories such as Sultan Abdulhamid’s reign, memories of World War I, Refet Pasha’s entrance into Istanbul in 1922 and the death of Atatürk. She lived her life as an Istanbul lady rather than an Azerbaijani. That’s why I called her “Istanbulite grandmother” in my poem. She wasn’t given the opportunity to study and wasn’t familiar with any of the alphabets. My Urmiye-born paternal grandmother, Rubabe Hanım, on the other hand, truly lived her life as an Azerbaijani lady. As she moved to Istanbul when she was nearly fifty years old and was hard of hearing, and she only spoke Azeri Turkish. As she was not given the opportunity to study, she did not read either. Because my maternal grandmother had lived in Istanbul after the age of twelve, she did not know the Karbala laments very well. I and Hüseyin would listen to the Karbala laments sung by our paternal grandmother. The Karbala laments and a couple of Azeri songs of mourning had been engraved in her mind. When she was crooning laments, she would cry, and when she was humming a folk song, like “I flew a hawk from castle to castle” she used to smile.

My maternal grandmother did not sing laments or folk songs. Although she was never interested in radio, our maternal grandmother pricked up her ears and listened with joy when she heard the strains of “Teeny-Weeny Stones of Sarayburnu” or “Waiting on the Island Shores”. I guess it was in 1955, in a book of Refii Cevat Ulunay, that the first verses of a certain semai song performed in Istanbul’s coffeehouses were recorded. “Efendim Hu, Nasibim bu, Tecelli taksirat yahu.” My brother Hüseyin wanted to test how really much of an Istanbulite our grandmother was with those verses. Although I had said, “She is a lady who has never stepped into a coffeehouse, she cannot have heard it”, he did not listen. When Hüseyin, approaching the sofa on which my grandmother sat and napped, said “Efendim hu”, she opened her eyes and completed the verses by cheerfully saying “Nasibim bu, tecelli taksirat yahu” from the semai. Thus, Hüseyin won the bet. In my grandmother’s colloquial language, there were also words that had been transferred to Istanbul Turkish from Greek and Italian. My paternal grandmother lived in her own world and made no effort to learn such words. One of my maternal grandmother’s famous words was the word “kumpanya” (company). She used to call the gas company the gas kumpanya, and the electricity administration the electricity kumpanya. The word kumpanya was also in the rhymes of children of Istanbul until the 1960s, for example, “aya maya kumpanya, bir şişe şampanya”. In 1966, when my grandmother died, as the word kumpanya had become associated with the Catholics living in Turkey, it seemed to me as if the word’s burial also took place in the Feriköy Latin Catholic Cemetery.

My other grandmother would not listen to the radio, and even if the radio was on she would not pay attention. She only spoke Azeri Turkish. One day, my brother and I heard a bizarre word from her. She had said that a physician named “Fehlettubba” had treated her when she was young, in the city of Dilman. After my father came home that night, he solved the mystery of this strange word. This word was not a name, but a title given to that physician. She had misunderstood the title Fahrü’l-etibba, that is “Commendation of the Physicians”, as “Fehlettubba” and remembered it as such.

You mentioned the owl making a nest under the roof of Nadire Hanım. The animals had a special place in our old neighborhoods. I remember a very nice article by Refik Halid about street dogs.

I remember a friendly white dog named Medor, who was one of the street dogs. Our household, except for my father, was fond of cats more than dogs. My father loved the German shepherd and the sheep-dog, but my grandmother, who performed the daily prayers at home, would strongly oppose him, claiming that dogs would make the house dirty. My dad would daydream about his future farmhouse that would never be realized and would fantasize about the German shepherds and sheep-dogs he was going to feed in a spacious garden. Medor was the public dog of the street and he was white. He came to the street in 1947 and disappeared in the 1950s. In 1943, when we moved from Kurtuluş to Çobanoğlu Street, the neighborhood street dog was black and disappeared in 1946. Its name was Bobi. A dog in the neighborhood that was not a street dog was a female dog named Linda, which belonged to the Italian wife of Sahure Hanım’s landlord, Monsieur Istrati. They lived without a dog for a while after Linda’s death and then named the white street dog Medor. However, content with him as only a guard dog, they did not take Medor into the house. As the cat subject will take long, I am not getting into that. The street did not have a neighborhood cat. As cats were backyard visitors, Çobanoğlu Street only had public dogs. The garden cats were the cats of the alley street, Kuyulubağ.

Did you have a stork as well, hocam?

We had them, of course. On the chimney of Haydar Bey’s house; Haydar, a resident of Kuyulubağ Street and our backyard neighbor, every summer between 1943 and 1948 a stork family used to make a nest. While our acquaintances residing in Kadıköy and Üsküdar found this scene normal, for the guests coming from Cihangir and Taksim, where there were no storks left, both the stork nest and the owl nest were very exotic. At the end of the 1990s, in a suburb of Seville, Spain, I saw ten pairs of storks—that’s twenty storks—on about ten chimneys of an old barrack-like building. So, storks had not left Andalusia. I wonder if there are still storks in Balıkesir, Orhangazi or Çatalca? I have not been able to travel there after 1996. Every Istanbul residence who made trips to Silivri between 1980 and 1990 would see a stork in the summer months. Actually, more than one. In the 1990s, storks became rare on the highways. It was only in 1995 I suppose. I saw a majestic stork in the Aydınlı village of Çatalca. Also, in 1992 while I was on the bus returning from Bursa, I saw a stork family and, pulling a piece of paper from my bag, without any hesitation, I wrote the poem Muhayyer Sünbüle; it was as if it was being dictated to me. Also, in 1996, just before heading to Çanakkale from Balıkesir, I again saw across a healthy stork family.

In Feriköy in the 1940s there were not only storks and owls. There were predatory birds, kites, whose dignity was less than that of a falcon or a hawk. They raided flocks of sparrows and made them scream until they caught an ill-fated one. The same birds reigned in the skies of Istanbul as if they were falcons or hawks. Why did they disappear after 1970? Was the disappearance caused by pesticides? Or was it because they were hunted like falcons and hawks and sold to Arab countries? We need to ask an ornithologist this question; indeed, I have actually asked some biologists. But because they all had been born after 1970, they were not aware that kites were wafting in the Istanbul skies before he was born.

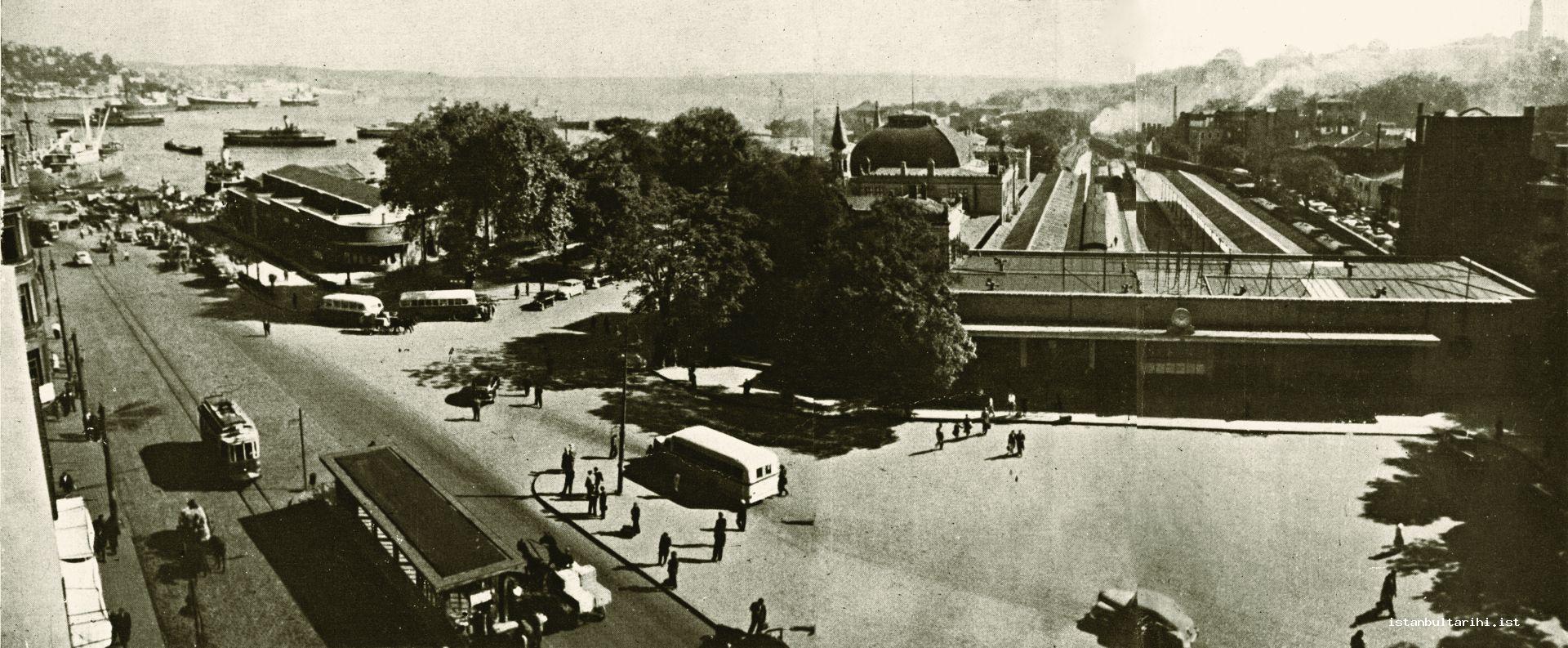

Swallows were also distinguished birds in Feriköy. A favorite place of the swallows was the Göztepe train station building. The swallows started to abandon Feriköy in 1950, but in the 1960s they were still sufficient in number at Göztepe station. However, in 1999 there were no more swallows at Göztepe station. In the year of 2006, I saw plenty of swallows in Denizli, Pamukkale. The people of Denizli need to look after the Denizli rooster well, and also the swallows. We heard from the owner of the house across from ours that a weasel had been seen in the backyard of that house.

Between 1943 and 1950, large flocks of bats were found on Feriköy Çobanoğlu Street. Afterwards, they completely disappeared. My brother and I came across a hedgehog for the first time in 1944 in Kısıklı Çamlıca. Later, we never saw a hedgehog in either Feriköy or Göztepe ever again. In 2008, in the rural part of İnönü University’s housing area, I saw a dozen hedgehogs scampering around in the dusk. The residents living in Malatya should be careful not to harm the hedgehogs.

Hocam, it is apparent that you know the rural areas of Istanbul well. Was the tradition of going to excursion places common when you were young? Would people go for a picnic, for example?

There are some people who think that picnics were unheard of in the 1940s or the 1950s, with this tradition starting after 1960. This is an imaginary judgment made by those who do not know Istanbul. On the contrary, despite the rigors of transportation, the picnics people had in Küçüksu, Kuşdili Çayırı and Kağıthane, which is called “going on excursions,” were famous. In the 1940s, family picnics in traditional families were mixed. Ladies who were from different families but were friends would organize a group picnic two or three times a year. Although the number of houses with a telephone was not great, Seriye Hanım from Üsküdar, Hacer Hanım and Fatma Hanım from Fatih, Sara Hanım from Bebek, and my mother would do their best to convey to each other the place and time for the picnic. I’ll describe the favorite location of my mother’s group for excursions: in the 1940s, when Samatya Istanbul Hospital had not been built, and thus accordingly the coastal road no longer existed, there was a woody area in Samatya-Yedikule, past the railway, across the hill and down an escarpment. While the mothers and aunts would be busy preparing the meals, the boys had the opportunity to go down the hill and swim. Girls aged nine or older were not allowed to swim, because even if just one or two, there would be some uncouth boys who would harass the girls. These louts could not be seen in Beykoz or Küçüksu—heaven knows why. The places where these louts could be found were around Yenikapı, Samatya or Florya, although they were rare. Almost all of the ladies would bring the classic picnic food.

What was eaten at the picnics?

Meatballs, French fries, stuffed grape leaves, stuffed peppers ... For drinks, water would be brought from the neighborhood picnic fountains. In the 1940s, there were no bottled drinks other than soda. The other picnic areas for our group were in Florya, Küçüksu and Beykoz. I don’t know why Sarıyer was not one of them. The last picnic that I and my brother Hüseyin joined was the Küçüksu Picnic, in 1951, when we were 13 years old. My elder brother was a medical student and was twenty years old. It would have been strange for him to be invited to the picnics in which men did not participate. Hüseyin and I were figures with breaking voices. We had other peers who were in the same position. Picnics to which children could not go were also unappealing to the ladies. Strange men wouldn’t approach groups that included children; a group of only ladies, however, would be attractive to them. These reasons were never discussed explicitly, but they could be understood. For these reasons, and also because Istanbul was becoming more and more crowded and because the people felt less safe than in previous years, the ladies’ picnics disappeared. The mixed-sex family strolls, for example going to Karakulak Stream, eating yoghurt in Kanlıca, or eating börek in Sarıyer, lasted until the 1970s. Afterwards, because new generations did not enjoy having picnics with the elderly members of the family, the “picnic autonomy” period for families ended; soon after resorts, hostels and hotels grew in popularity and picnics became outdated.

How long did you live in Feriköy?

In 1957, we moved to Göztepe, near Merdivenköy. We found large number of frogs in the Merdivenköy creek and in the garden of Fahrettin Kerim Gökay Pavillion. Since 1964, I have been residing in Levent and my brother in Teşvikiye. In Levent, I have continued to greet the kites, doves and frogs that I often came across in Göztepe and Feriköy.

In one of your poems, you mention Çukurbostan turtles.

Yes, the gardens that run along what is currently Kızılelma Street, the large garden that stretches from Feriköy Çobanoğlu Street to Okmeydanı, the area full of blackberries on which skyscrapers stand now on Levent Karanfil Street, the woods on the ridges of İnşirah Slope going down to Bebek, the green area near Feriköy Acropolis Casino, Etiler Çamlık, which starts after Dördüncü Levent, and which now hosts university housing, the vast green area that stretches past Sahrayıcedit, and many more places were habitats for wildflowers and turtles. Urbanization has eliminated the habitat of many turtles. In my “Çukurbostan Turtles” poem, the “dignified aghas with khaki robes” were the ancient turtles. In the middle of the 1970s, the kites disappeared as well. Coming across doves and frogs became a rarity after 1980. Turtles disappeared in the 1990s when the skyscrapers emerged. The numbers of locusts and mantises I saw in Levent diminished terribly in the 1990s. I do not know whether this might be related to pesticides. Again, this is a matter to be investigated by zoologists. Now I miss the grasshoppers that thrived before the 1980s, the mantises, green lizards, and even the ants’ nests that I often saw, but no longer come across much.

In some years in the 1940s and 1950s, there were bonito fish invasions, which delighted Istanbul fishermen and Istanbul folk. Bonito was not very popular among families of a high income and was considered to be a “banal” fish. It was a large fish that fishermen called the “ocean lamb”... This was either in 1953 or 1954. There was another bonito invasion. We would travel home on the tram from Beyoğlu Atatürk High School for Boys, preferring not the red first-class tram but the green second-class one. There were very few people taking bonito home among the first class commuters. During a bonito invasion, the second-class tram would smell like fish as many people took their bonito home. A handsome, well-dressed, boy who looked like an actor, no more than 17, raised his voice when he saw an old man getting on the tram which stank of fish with a bonito, sticking its head out of the paper bag: “The stink here is killing us already. And now here’s one more. All the children, cats and dogs at home will eat fish.” In those years, sixty years ago, such treatment of an elderly by a youngster was enough to cause a fight to break out. However, the young man was very well-dressed; as the old man looked very down and out, he preferred to keep quiet.

As a child and teenager, you lived through the “Era of the Radio”. What do you remember about what was on the radio in those years and the people’s musical taste?

Until the 1950s, every middle-class family had one Aga-Baltic or Phillips radio. There were families who allowed their children to listen to the radio, but in many families, and in ours, the children could only touch the radio when they started high school, that is, at the age of thirteen. This was true for me and Hüseyin as well. During the 1940s, only my father used the radio. My older brother Nadir Hatemi would listen to Turkish tangos and English or French songs, called “light Western music” on the radio until my father came home. My brother, who sometimes listened to Western classical music, was the person closest to Western culture. The fact that he was a student at Saint Michel high school played an important role in this. However, he did not abandon classical Turkish music. While studying at medical school, he attended the newly-founded university chorus, making friends with Dr. Abidin Gerçeker, who was one or two years older than him; he raved about Dr. Alaeddin Yavaşça, who was an assistant during his education in the Haseki Obstetrics and Gynecology Department. In our childhood Hüseyin and I never liked dance music or tangos. I was a faithful listener to the Sadi Yaver Ataman Chorus during my high school years. Thus, I added folk music to my favorite Turkish music. If we had had the opportunity to listen to Western classical music on the radio or records in our childhood, we would certainly have loved it like our older brother. But, we only came to love the polyphonic music that we could not listen to in our teenage years when we entered our thirties.

I know that after you started medical school, you lived in Suriçi (within the walls). Would you like to talk about Suriçi, or as the elderly call it, “the soul of Istanbul”?

During the 1940s and until the end of the 1950s, when people said Istanbul they were actually talking about the Suriçi area and the old Byzantine area, between the city walls in Topkapı, Edirnekapı and Silivrikapı city walls and Eminönü. Regions like Bakırköy, Yeşilköy and Florya were “suburban” residential areas which could be reached via commuter trains from Sirkeci. In the 1950s, the names of regions like Sağmalcılar and Taşlıtarla, today Gaziosmanpaşa, were known from the cries of the minibus conductors. Districts like Ataköy and Merter appeared in the 1950s. The Suriçi district contains the oldest neighborhoods of Istanbul, residential areas since the Byzantine era. Eminönü was a very prominent trade center, along with Yeni Cami, the Spice Bazaar, Hocapaşa, Tahtakale, and Rüstem Paşa Mosque. While the clothing stores in Beyoğlu and Karaköy appealed more to the “Europeanised” people, Sirkeci and Sultanhamamı stores appealed to conservative Istanbul residents and people who had migrated to Istanbul during the Republican Period. When I graduated university, I could only peer into the restaurants around the Sirkeci Station and music hall from the outside. However, in the Sirkeci of the 1960s, there were still traces of the Sultan Aziz and Sultan Hamid periods. There were a number of buildings that did not create a sense of nostalgia in me and that I was happy when the warehouses of Sirkeci were torn down.

What warehouses?

These belonged to the cargo companies of that time. For example, a wholesaler in Eminönü wants to send an order to Samsun. There would be a wooden crate in the wholesale store; the shopkeeper and the apprentices filled the chest and nailed it down. The shopkeeper would pick up a paint brush. After immersing the brush in ink and writing down the name and address of the consignee, he would call a nearby barrel-maker, who made a living in the following manner. The barrel-maker would stretch and clamp steel springs onto the back and the front of the chest. Afterwards, a porter would be called – these could be found, hanging around in groups of five at least, on every commercial street in Eminönü. They were known as hamal. We always felt sorry for these men. They would carry loads of approximately 30 kilograms on their backs; most of them worked with streams of sweat pouring down their faces and would complain about backaches. After receiving his fee, the porter would pick up the load and carry it to the warehouses in Sirkeci. The warehouses, at this time, would transport these chests to their destination by train, ship or truck. Whether due to the increase in road transport or for other reasons, I am not sure, the warehouses died away in the 1980s. During the years when warehouses and porters were still functioning, there were also plenty of horse carriages. Haldun Taner’s stories depict those years very well. I would say to a young person who is reading the story It was raining on Şişhane that “The Istanbul described in that story is exactly like the Istanbul of the 1950s”. In the 1950s, Refii Cevat Ulunay and Refik Halid Karay were alive. Their departure from this world was in the second half of the 1960s. We read of Istanbul’s bullies and bohemians in Refii Cevat. In addition to Ulunay’s narrations, Refik Halid would depict Beyoğlu’s entertainment world. We cannot feel the spirit, the heart and soul of Istanbul without reading about the lives and memories of the two authors, Sermet Muhtar Alus and Haldun Taner. Also, female authors, such as Semiha Ayverdi and Münevver Ayaşlı, help us to understand the spirit of Istanbul.

Hocam, this interview is exactly what I wanted. Now we are in Sirkeci, we have passed Haydarpaşa train station and we are climbing up Ankara Street, now the journalists’ hill...

Ankara Street takes us to Babıali (the Sublime Porte), which was perceived as a street of pens and opinions. To the right of this street, going towards Beyazıt, at the part nearest to Sirkeci, was Semih Lütfi Bookstore; along the same way path, going up the hill were Ahmet Halit Bookstore, Kanaat Bookstore, and then İnkılap and Remzi Bookstores. Between Kanaat and İnkılap was the Linguaphone Institute; during these years, this place appealed to people who wanted to learn a foreign language. As far as I remember, people attempted to learn a language via sets of 15 to 20 78 rpm records; they bought these for the equivalent of 500-600 TL in today’s currency; they would either sell these records at a loss or give them to a student in the family. Across from Remzi Bookstore, at the current location of the Ministry of Culture, was İbrahim Hilmi Çığıraçan Bookstore, which had stood there since the Ottoman period and continued to exist until the 1960s. Hüseyin Rahmi Gürpınar’s novels were included in the catalogue of this store, in addition to translated works such as Tagore and Life of Benjamin Franklin. Let’s continue: walking along the Provincial Hall, we pass İsmail Hakkı Akgün Bookstore, which sold law school books, being at the point nearest the Ministry of Education. Veering to the right at Remzi Bookstore, on the left of the slope that takes us to Cağaloğlu from the Iranian Consulate was the Maarif Bookstore of Naci Kasım Bey, who published the Saatli Maarif Takvimi. The Maarif Bookstore is still situated there.

You must have seen some of the famous authors, poets and journalists of the era on “our slope”.

Of course I didn’t get to see the Babıali of the 1930s. During that period, it was possible to see Ahmet Haşim, Nazım Hikmet, Peyami Safa, Vala Nurettin, Semih Lütfi, Ahmet Halit Yaşaroğlu, Vedat Nedim Tör and many other authors there. I began walking around Ankara Street between the 1950s and 1966 and saw Yaşar Nabi Nayır, Peyami Safa and Refi Cevat Ulunay, as well as the founder of Remzi Bookstore, Remzi Bey, and İbrahim Hilmi Çığıraçan. In 1954, I saw an elegant and cultivated couple, Refik Fersan and Fahire Fersan, while I was leaving Istanbul Radio. In 1961, I saw Ahmet Kutsi Tecer on the Kadıköy ferry. I saw Behçet Kemal Çağlar in Taksim a couple of times. In 1964, on Nispetiye Street, I saw Şerif Muhittan Targan and his wife Safiye Ayla, walking arm in arm. I was among the naive Istanbul residents who met and greeted Iskander Mirza in front of Gülhane Park. I have many other memories of such special encounters.

Babıali was the center of the media. In the immediate vicinity, in the cafes, restaurants and bookstores it was possible to encounter a number of authors or poets. In those years, which newspapers and writers did you use to read?

In the 1940s, only one newspaper was bought by middle class families. Higher income families would buy two. For many households, paying for a newspaper was a luxury, and it was contrary to the principle of “cut your cloth according to your means”. The Akşam paper was bought daily for the home. People who picked up Akşam would be aware of the style of Necmeddin Sadak and Vala Nurettin. My father did not give up the Akşam paper until the 1950s. After 1950, he sometimes bought Sedat Simavi’s Hürriyet or Safa Kalışlıoğlu’s Yeni Sabah. My uncle in Aksaray did not give up the Son Posta newspaper. Some days my father would bring three or four papers so that we could keep up to date with what was going on around us; we would be very happy. Ali Naci Karacan, who had migrated from Iran to Turkey during the Ottoman period, established the Milliyet newspaper. After his early death, his son Ercüment Karacan inherited the newspaper. In the 1950s and 1960s the most popular paper for high school and university students was Milliyet, while the older people and the middle class favored Hürriyet, and the retired civil servants, retired dignitaries, retired teachers and officers, and the middle class also read Cumhuriyet. Cumhuriyet was a formal and somber newspaper; I mean it was completely different from today... After 1985 it took the form of a “revolutionary” in a t-shirt. However, it wore this garb over its necktie and jacket. Milliyet was adored by all high school and university students during the 1950s. Two comic strips, Abdülcanbaz and Hoş Memo, the former of which was local and the latter an example of American humor, gave the young people a lot of pleasure. The papers of the minorities were the Armenian Jamanak and Marmara, Şalom which was published in Turkish and Ladino (Jewish Spanish), and the Greek Apoyevmatini.

Probably, the number of Ladino speakers was quite high in Istanbul in those years.

Let me put it this way: in 1949, my brother and I took a roundtrip to Eyüp on the ferry. It was full of Jewish citizens who resided in the Golden Horn region. Nearly half of the passengers spoke French and the other half spoke Ladino to one another.

Hocam, let’s continue to Sultanahmet.

In Sultanahmet there were not as many tourists as there are today. We would have the run of Hagia Sophia and the Blue Mosque; in the former, we would stroll around, and in the latter we would pray in the serene and luminous blue environment. In either 1953 or 1954, I visited the Archaeological Museum for the first time and wondered to myself about how such impressive statues and sarcophagi could be replicated with such paltry copies in the history books. In Topkapı Palace, there would be a few more tourists. Tourists, until the second half of the fifties, were either called “travelers” or “foreign travelers”. “Foreigners” from America or Japan were not common in Sultan Ahmet or Topkapı. European visitors were French, English, and German; Eastern visitors were Syrian, Iraqi, Jordanian or Iranian. And their number was not as great as it is today. The annexes of the Mahmut II’s mausoleum were used as a government office. The officers would not let anybody in, saying that “the manager has given this order.”

Now this building is being used by the Istanbul branch of the Turkish Ocak (Guilds).

Is that so? I was not aware of that. I learned about the opening of the mausoleum to visitors perhaps a little later, in 1994, and I went to visit that region with great pleasure. Another place I was curious about was the Yeni Cami Hünkar Mahfili (sultan’s prayer area). However, in 1986—I do not know, maybe it was 1986—when I went to see it, a solemn guard with a mustache prohibited me from entering. “I rented this place from the waqfs, you cannot enter!” he said. Due to the bitter resentment I felt, I still haven’t been to the Hünkar Mahfili. Now, thankfully it is no longer a carpet store.

Yeni Cami Hünkar Mahfili was successfully been restored by ICoC. Now the ramp section is being used as an art gallery where exhibitions are held from time to time. What about Beyazıt Square?

Beyazıt Square fascinated all Istanbul residents, particularly children. There was a large marble pool in the middle of it. In the summers of 1951, 1952, 1953, and 1954, my brother Hüseyin and I would sit on the edge of the pool, happy with the spattering water from the fountain on our faces; we would then jump on a tram and on the way we would flip through the books we had purchased from the second-hand bookshops. Again during a summer holiday, while on the tram we were flipping Musahebat-ı Edebiye, which we had bought from second-hand bookshop; an old man beside me—probably a modernist one— roared, “You are young, follow the alphabet reform. Put aside these religious books!” I guess that he had been born around 1910 and thinking that he knew the old alphabet, I put the book in his hand; understanding that the topic was literary conversations, he went quiet, saying abashedly, “Good, but still do not neglect your classes”.

In those years, there was no police checkpoint at the gate of Istanbul University’s central building. Anyone who wanted to see the university garden or the Beyazıt Fire Tower could go in. The entrance was free until after May 27. In 1968, and particularly in 1970, young people made this building appear ominous. Both inside and outside of Süleymaniye Mosque there was a climate of serenity and forgiveness. However, already in 1956, Beyazıt Square had been bastardized into a sort of sloped maze. In fact in those years, two years prior to May 27, Süleymaniye was regressing as well. In the winter of 1957, on the road leading to Süleymaniye from the left of the university, I witnessed a scene: a barker was acting inappropriately in front of a tent, shouting as he rang the bell in his hand, “We have found the Şahmeran (legendary creature, with the body of a snake and head of a human) with great sacrifices. Oh my God, you create such things! Such things!” He was deceiving gullible customers, that is raw army recruits, on weekend leave; they paid 2.5 or 3 liras in today’s money to see this freak show.

This type of tent-theater generally would travel around Anatolia. So, they were able to find gullible people in the heart of Istanbul.

Yes, in the heart of Istanbul ... That Sunday, I went home feeling very depressed. “How distorted Beyazıt Square gets on Sundays, although it used to look like the center of culture with its university, mosque, and second-hand bazaar!” I thought to myself. This distortion occurred after 1956, when Beyazıt Square became messed-up. How do I know that? During the five hundredth anniversary celebrations of Istanbul’s conquest, one Sunday my aunt’s husband, Rıza Müşfik Bey, was showing his children, me, and my brother around Beyazıt Square. On that day, in Beyazıt, purity emanated from the mosque, the university gate, and the white marble fountain. However, on a Sunday in 1957, the ground was crooked and uneven, covered in paper and cigarette butts, and people were screaming “Oh God you create such things!” causing us to drown in the noise…

Now, assuming that we are heading from Beyazıt to Aksaray... what do we see?

In the middle of the street that takes you to Aksaray from Beyazıt Square, there was a tree-lined sidewalk, just as there was between Harbiye and Elmadağ. I am not sure whether it was necessary, but those trees were uprooted during the construction activities in the Menderes era. Across from the Faculty of Arts, a door that displayed the words Simkeşhane-i Amire in exquisite taliq calligraphy stood; it has since been removed. I wonder where this inscription is now. If it has been preserved, it would be nice to recreate it on the façade of the Simkeşhane building, like a monument, to say that there was once a state studio that made silver wires there.

The front side of Simkeşhane was destroyed in order to expand Ordu Street. It was one of the undesired results of the reconstruction which Adnan Menderes hoped would relieve Istanbul from the neglect during the single-party regime; however, this led to the destruction of many historical buildings. What do you remember about these reconstruction movements?

In the 1950s, the constructions of Vatan and Millet Streets began. Many a wooden mansion, ancient tomb, and even mosque vanished. I wish we had been financially better-off in those days so that we could have created an Aksaray-Yeşilköy route via a different route, using a bridge to reach the Golden Horn. However, our financial situation at the time did not allow for this, and our engineering was not as good as it is today. Neither was it possible to avoid the widening of Vatan and Millet Streets. One day in 1954, my aunt went for a check-up to the Guraba Hospital. As we were staying with her family that day, she took me with her. We got on the Topkapı tram from Aksaray. I wish I had today’s technology in 1954; how interesting it would have been to film this tram trip. The tram was not travelling as it goes now, along the straight Millet Street, but progressed by spiraling through the narrow streets, which were completely full of wooden houses. The district names that we see along the straight line now were stops on these helices. So the tram would travel from one stop, for example, Aksaray, Yusufpaşa, Haseki, Fındıkzade, or Çapa, to another, making spirals as it went.

During the years you were in medical school, these streets must have been completed; as a result, the appearance of the street must have changed a great deal.

In 1962, I graduated from medical school, and in 1963 I started specializing at Haseki Hospital. Between 1962 and 1968 those neighborhoods changed little. In the back-streets between Haseki and Cerrahpaşa, the views portrayed by Halide Edip Adıvar in her novel Sineklibakkal (The Clown and His Daughter, 1935) were still visible. The back slopes of Topkapı and Guraba coming down to the Sergeant Officer’s Club still looked like old Istanbul streets. The area where fires were once common, between Vatan Street and Fatih, was quickly filled with massive buildings. The two sides of Kızılelma Street—at one time a garden—were full of brick buildings, not wooden houses. However, Kocamustafapaşa, Cerrahpaşa, the nearby Bulgur Palas and Etyemez districts preserved their wooden buildings. “Even if death is a single night in an alien realm / let home appear in my imagination as it was,” said Yahya Kemal, and his wish came true. Istanbul and Turkey changed a great deal during the ten years following his death.

Hocam, I would like to ask what you remember of Taksim from the 1940s and 1950s, which is always in the limelight. When did you first walk through Taksim?

I will never forget a spring day in 1945; we were returning from my aunt Akile Müşfik Hanım’s in Aksaray. We always got off at Harbiye and wait for the Kurtuluş tram there. Peyami Safa’s Fatih-Harbiye tram was the one from which we got off. My mother was very curious, but under the conditions of this time, a lady would never go on journeys alone; she used the pretext “the kids want it,” even for visits to the cemetery and the cinema. That day the three of us went to Taksim to see the Atatürk Memorial—back then monuments were called “memorials”. We got close to the memorial. Atatürk, İnönü and the other people in the memorial seemed like they could see us and were watching us. Atatürk died the year we were born. However, the other people were still alive. At that time, as our dear people were inclined to pick the flowers, there was a park warden with a whistle in a grey suit and cap. The warden suddenly began to blow his whistle. Upon the sound of the whistle, Hüseyin and I came out of the hypnotic trance into which the statue had put us. When we looked around, we noticed that a lady of my mother’s age, in a worn coat, was about to pick a violet, probably to wear on her lapel. She slowly shrank away in shame. The warden went on flouncing around the monument with the pleasure of a person who has prevented a crime.

Was it when it was uttered: “That’s forbid’n man!” that things became set in time?

Presumably, it was that Republic Day in which my father, my brother, myself and Hüseyin went to Taksim Square; after that, every Republic Day, day and night, we would go there until 1949. In the daytime, we would watch the tanks, gun carriages, and the soldiers’ parade. At night, we would watch the people setting off the fireworks, and occasionally we would watch the torchlight procession; during almost every visit we would see the lights reflected on the water that flowed along the wall next to the Maksem building. From 1949 until 1953, we would go with just our older brother. During the 1953-1954 academic year, however, we became students at Beyoğlu Atatürk Boys’ High School. We went through Taksim Square every day. Then, we only went to the daytime celebrations. After 1957, circumstances in Istanbul changed. National enthusiasm faded away. The minorities experienced the pain of the September 6-7 Events, CHP supporters experienced the pain of “a stone being thrown at İnönü” and Democratic Party members had the worries, expressed as: “Oh, you Ismet Pasha! Who knows what you intend to do!”

Starting in 1955, I did not go to Taksim Square on Republic Day. After a while, the ceremonies were moved to Vatan Street. I have two memories from the 1957 elections. The first one was when İnönü was coming to Taksim one Sunday for an election speech. It was the year when Hüseyin and I had finished our first year at university. We made it to Taksim from Göztepe. Seeing that it was impossible to enter the square, we veered off to Tarlabaşı and from the back street we came out in front of the French Cultural Center. We had never seen such a crowd before then. Hüseyin said, “We might as well go back home”. The crowd was massive, lining İstiklal Street as well as the square. At that very moment, either a provocateur or a stupid supporter of İnönü, I still do not know which, a frail man with a thin mustache and a cap started pushing the people in front of us and shouting “Oh Lord, thank you for allowing me to witness these days of Master Ismet. Push! Push!” At that age, even when faced by death Hüseyin and I could not call for help, we were frightened that we would look ridiculous. Because we did not push anyone, we were not able to remain standing between the front and the back row of people. When we were about to fall to the ground and be crushed, we clung to the metal advertisement pole in the shape of a coin bank, which had been placed by İşbank that year in front of the French Cultural Center. I am still grateful to that advertisement pole and the coin bank.

You mentioned two memories.

Oh, yes. My second memory is this: somewhere near the beginning of Mete Street, Reşat Ekrem Koçu, who was a parliamentarian candidate from a party, the name of which I cannot remember now, was going to deliver an election speech. It was not a Sunday. As it was still holiday for the universities, I went to the spot mentioned in the newspaper ad, this time alone. Although I was half an hour early, there was nobody in the part of the square where you can see Mete Street. I would like to have seen Reşat Ekrem Koçu, whose articles I enjoyed reading. At the hour and minute specified in the notice, Reşat Ekrem Koçu appeared, a white-haired grandfather wearing thin wire glasses, accompanied by someone holding a scratchy microphone in one hand. The microphone was set; he checked his watch and started his speech. Ten listeners, consisting of helmet-wearing construction workers, and myself were in the vicinity. That was the total crowd. The helmet-wearing citizens were happy that this was the case. Because this great man would be able to speak to them face to face and from only a few steps away. While other election speeches were a scuffle, the summary of Reşat Ekrem Bey’s speech was that “Menderes wants to separate the Istanbul province and municipality. No way sir, no way! Istanbul is a unique city. Even the Ottoman Sultans had not done this. Is this possible?” The helmet-wearing citizens, as if responding to their own uncles, said “noo way!” and Reşat Ekrem Bey smiled wanly and ruefully. He became an MP candidate in the 1957 elections and departed from this life in the 1960s.

I did not know that Reşat Ekrem tried his hand at politics and was an MP candidate. Hocam, I am grateful for this unique conversation.